by B. W. Allred

The story of Stephen Hampton Worthington is the biography of a practicing Christian. Hamp, as he was called by young and old, would be the last to classify himself in such a role. He was not the indoor variety of Christian that practices according to rote and operates within the metes and bounds of prescribed rules. He was the kind that helped a man out of a bog hole, saved a neighbor's cow from bloat, or helped a stricken friend with services and money.

He was a simple, modest man that never spent his time proclaiming his holiness. The God-fearing found him a wholesome companion and the Godless were given a fair hearing.

Like Thomas Jefferson, he had humane democratic instincts. He recognized no caste as superior or interior and granted everyone the right to let his talents flourish. His life was an example of correct living and democratic tolerance. He never cackled over the sins of others or quoted the current tattle about the misbehavings of his friends and neighbors.

He was a solid citizen, but not in the commercialized modern meaning of the term, for he was the kind that keeps a country stable, tied together and growing. His kind symbolizes great mass movements and actions of an era and an epoch. People don't build personal monuments to such men, though well they might; they build monuments to groups of his kind to symbolize events like: Mormon Immigrants Crossing the Plains to Utah: Pony Express Riders: Trail Drivers: Agricultural and Social Advancements. We can live without heroes, but we cannot live without wheel-horses and Hamp was a wheel-horse.

About every constituent in the cells of his body originated in Tooele County soil where he spent most of his life. He and his bride moved into the original rooms of their Grantsville home on Clark Street where they lived until his death on August 3, 1948.

*Hamp was born in Grantsville, Utah, April 21, 1876. His father, Stephen Staley Worthington, was a Mormon pioneer who came from Pennsylvania to Utah along with his parents, James and Rachel Staley Worthington. His great grandfather, Isaac Worthington, was born in England. Hamp's wife, Annie Josephine Johnson, known as Mollie, and Hamp's mother, Joan Eliason, were of pure Swedish immigrant stock. In addition to his father, James Worthington, Grandfather Stephen Staley Worthington pioneered in Utah. Some of Stephen Staley's brothers helped settle the Canadian province of Alberta near the towns of Cardston and Lethbridge. Grandfather Worthington founded a large clan that numbered about 100 living descendents by August 1948.

**Written as a memorial statement by his son-in-law,

B. W. Allred.

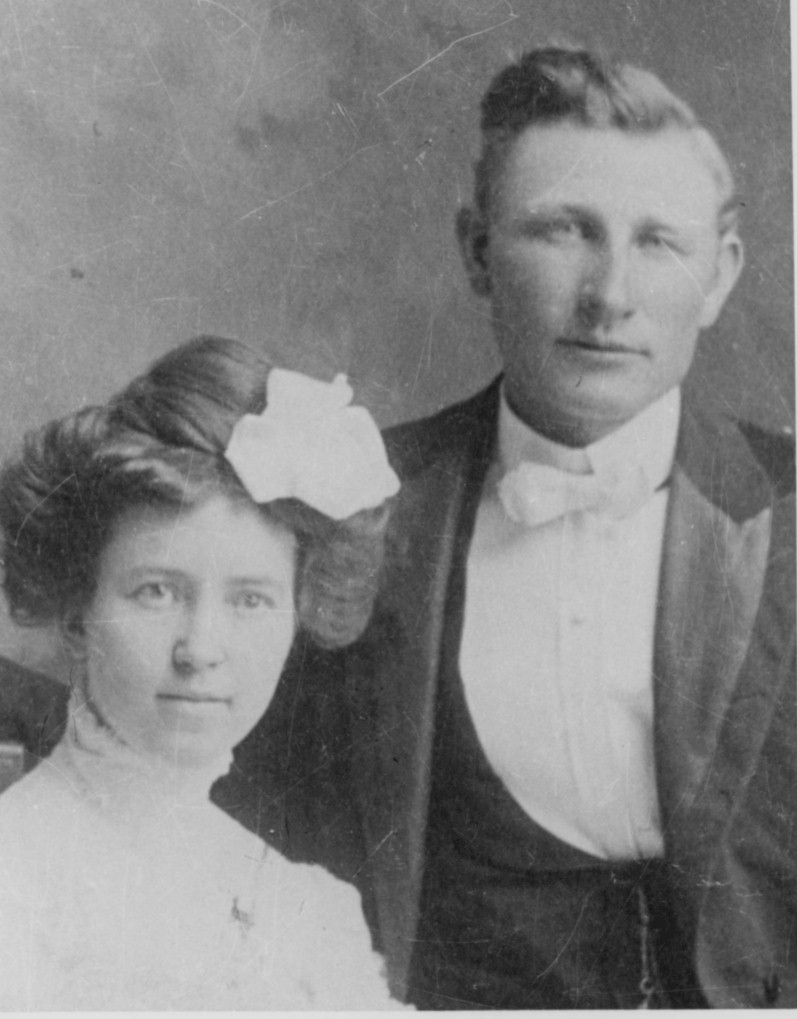

Hamp married Anna Josephine Johnson, known as Mollie, October 30, 1902. Their companionable and exemplary life is a story by itself. Mollie was born in Grantsville, Utah, June 12, 1880. She was the eldest child of Charles Johnson and Anna Olson Johnson. Grandfather Johnson was a Utah pioneer from Sweden who had three wives and his living descendents are numerous.

For a man rooted so deeply in Grantsville, Hamp was fairly well traveled. Of course his normal work of livestock raising, farming, brand inspecting, assessing for the county and prospecting gave him opportunity to see the highways and back trails of Tooele and adjacent counties. He probably knew most of the water holes and interlacing coyote trails in Tooele County.

By the time of his marriage, he had seen a lot of western ranges on horseback. On one trip, he visited his Canadian kinfolk. His northward trail led through the Shoshone Indian country of Wyoming and the Blackfoot, Crow and Sioux Indian Reservations of Montana. For days his saddle horses waded north through the wheatgrass expanses between the Yellowstone, Missouri, and Milk River Valleys and over the Sweet Grass Hills along the Canadian and U.S. boundary to the meandering valley of the Saskatchewan.

He punched cows and wrangled horses for a large operator around Las Vegas, Nevada, and in the vicinity of the now Boulder Dam. This was during the Tonopah, Nevada, gold boom. Then Las Vegas was just a spoiling shack and tent town. Freighters loaded at Las Vegas with grub, powder, lumber and tools for Tonopah miners. They drove sturdy high-wheeled, wide-tired wagons with as many as three of them heavily hitched together as a unit. They were pulled by 10 to 16 teams strung out and handled by one man with a jerk line attached to one of the leaders which was a well trained as a circus horse.

Las Vegas perspired with sin like an outpost of Hell. The flapping tent town couldn't house the surplus riot of men that rallied there en route to Nevada gold fields. There were more saloons than any other species of business. Most of the women residents ran or served in brothels, and there was too few of these to service the lusty patrons who wrangled and clawed during the desert night. Stabbings and killings were frequent. The faint ebbing of civilization was still submerged under the overburden of lusty, robust succor growth.

Hamp had an intuition for doing well anything dealing with his agricultural vocations and it was in agriculture that he made his living. However, he had a consuming and unquenched desire to strike pay dirt in a mine. He knew mineral ores and after his death, the family and friends found odd samples of ore from many known ledges in his trousers pockets, on his work bench, in tool boxes and under one bed. During a prospecting expedition, he was as excited as a race horse at the barrier. No one knows how many miles he made on foot and on horseback trying to find the lead from which some high-grade float originated. His old mining pick has pecked at untold outcrops that glistened in the sun and drilled into crusted embankments that might have concealed a vein of ore.

Like many others who had a passion for mining, he never gave up hope that one day he would strike a bonanza. In the family strong box, a tin bread box kept in the clothes closet, a few gilt edged certificates for mining and oil stock was found along with life insurance policies and other family papers. So far as is known, none ever repaid a dull sou on the investments. Life is a gamble and so is mining. It takes faith like his to explore and to find and to maintain an empire. Only a few strikes a rich vein of ore, but those who hit pay dirt also have to have the yearning for minerals and the guts to take a chance just like Hamp did.

Manifestations of his friend's good feeling toward him were displayed in a variety of ways. People liked him and sought him out. At Hamp's funeral, his life-long friend, Bishop Clark, paid Hamp the kind of compliment that would have pleased him most. He said that Hamp was one of the fastest and gentlest hands with cattle that he had ever known. He was a top hand at roping calves and was chosen to do the roping at many roundups. His organization and timing gave him speed and accuracy in roping. He could keep a ground crew of flankers, markers and branders on the hop all day. In a jiffy, he shook the coils of his lariat into a loop, roped a calf, jerked the loop tight, took his dallies to shorten the lasso to manageable length and dragged the bawling calf to the fire where the flankers downed him for branding. Later when age put a kilter in his throwing arm, he did the ear marking and castrating. With his sharp knife in his deft fingers, calves ears were cropped or bitted and bull calves were converted to steers with speed and with as much humanness as can be given in such operations. He seldom charged for these services because he liked to have a chance to keep his hand in the work he liked to do.

Hamp was a friendly man that had time for his friends. His life was not cluttered with the imaginary big things of life. He had time to serve his community, family and friends. He was an easy touch for little boys who needed odd jobs that paid. In the summer of 1947, two little boys bargained with him to weed his side of the street; the price was seventy-five cents. Hamp was not flush with cash and he had the time to do the job himself. However, he said he believed that the few dollars that he paid little boys to do small chores to provide candy money and experience and a small feeling of independence was cheap insurance and might help keep a few from matriculating in reform schools.

A good story teller is a boon to any community and Hamp was a depository of local history. He passed along the word-of-mouth-lore and legends of the county in true Homeric fashion. Once the family let a spare room to tourists in summer and roomers in winter and these he regaled with rich anecdote and colorful incident of the country. Occasionally when he had hooked a greenhorn and had him charmed and covered with goose pimples while recounting some of the harrowing Indian scalping expeditions, he embroidered his yard a little on the windward side in order to keep up the temp of his victim's pulse.

One of his famous windies went like this: "One hundred years ago, when I crossed the desert to California with the Donner Party which died snowbound in the Sierra Nevadas." From there he carried on with obvious exaggerations until his listeners discovered that they were being taken for a hay ride.

There is one local public project that Hamp helped sponsor and keep underway, which too many people fail to recognize as a major enterprise basic to human welfare. That is the Grantsville Soil Conservation District.

Local interest in soil conservation originated in early 1930 when Grantsville was about to become another Antioch. Antioch is the Ancient Assyrian city that became buried in the soil washed and blown from adjacent mismanaged and eroded lands. With monotonous frequency from 1929 to 1935, south winds collected dust from bare farm land and over grazed and burned off range land and peppered the town turning it into a suffocating Hall. Dust clouds rolled through the town and cut off vision; the fine dust filtered through window cracks and door sills then settled in food and finally on to beds where occupants rolled in misery in powdered soil that cut like diamond dust. Grit flitted past in heavy winds and shredded the living vegetation; sand piled up and blocked traffic; sometimes travelers were lost for several hours when caught in the boiling angry drift of a dust storm.

Desperate citizens banded together to fight this destructive agent that had risen up unannounced. They wondered how and why it had developed and what could be done to stamp it out. To correct it, they must know the cause.

The Soil Conservation Service was called in to help control the dust bowl. When the soil, vegetation, climate and past use of the area was checked, the reason for the trouble became obvious. The factors that were essentially responsible for the dust bowl developing had been set in motion as far back as pioneering times. Drought merely kicked it off with greater speed and menace. Scalped of the protective soil cover, nature was merely in rebellion and dust was given in retribution for man's mismanagement. The chronology of the developing dust bowl was part and a big part, of the local history that man had missed. He was more concerned about vital statistics of the human race and gee-gaws and gadgets than he was for his natural resources. The events that lead to the development of the dust bowl were strong out over a long time. The cause of the dust bowl was about as follows: livestock over used the native wheat grasses, blue grasses, Indian rice grass and other nutritious herbs. These good plants died or thinned out and the sparse sagebrush and other shrubs took possession and thickened into dense scrub forests. These shrubs are fairly edible and nutritious part of the year and animals survived when they were given supplements in winter. Brouse plants are not as good soil conservation plants as well managed grass, but they held off the wine and held down a good deal of water erosion.

Sometime before 1920, cheat grass, (Bromous tectorum) a winter growing annual from the Mediterranean regions, spread through the intermountain region where it became naturalized, and grew companionable with sagebrush where the good native grass had been grazed out. Cheat grass is nutritious when green and livestock fatten on it when they have plenty of it. It matures in May or June and turns to the color of a faded palomino horse hair. Dry cheat grass flames actively when fired. On good years, it provides continuous tinder on Grantsville ranges.

Years ago fires broke out and large areas of big sagebrush burned to the crown and died. Sage comes back slowly and that gave cheat grass almost exclusive control of the land. Early in 1930, over grazing and fire took off the cheat grass cover. When the south winds caught several square miles of ground bare, the unprotected top soil was blasted loose and Grantsville was on its way to becoming another Antioch. Dust storms scourged the country as vengefully as an ancient Passover.

There was only one way to dispel the erosion curse, all agreed, and that was to help nature grow back her magic carpet of protective vegetation. Since the problem was a local one, Grantsville land owners elected their own committee to cope with the problem.

They requested and use the technical assistance of the Soil Conservation Service range men, engineers and agronomists. The local land owner committee started the emergency soil conservation work. By 1937, Utah had passed its State Soil Conservation Act and in October of that year, the landowners voted for the Grantsville Soil Conservation District, which assumed local leadership and action for soil conservation work on the dust bowl and on the farms and the ranches of Tooele Valley land owners who asked for assistance.

These men harnessed the dust bowl and subdued it with grass. They gave the vegetation needful rests and lenient use until the bare ground healed with grass. Thousands of acres of crested what grass and other nutritious forage plants were seeded and their roots, leaves and stems held the land secure and the forage now supports the equivalent of 600 animal units of grazing per year. It is improving at a yearly rate which will out yield the present stocking figure.

This self-liquidating project took a lot of local initiative to engineer. The original local erosion committee and finally the five elected soil conservation district supervisors gave freely of their own time without recompense except that of seeing their community saved from the extinction because of erosion.

Hamp, with several of his friends, were largely responsible for originating and maintaining this fine job that kept Grantsville from becoming buried in sand drifts. He was elected for many assignments where the public was benefited because he was progressive, had an open ear and had sound judgment.

When a needful public job with no pay came along, busy-minded local people would say "get Hamp to do it, he has the time." Actually, Hamp had no more spare time than others. But he was unique. He was a friendly man who had time for his friends.

by B. W. Allred

The story of Stephen Hampton Worthington is the biography of a practicing Christian. Hamp, as he was called by young and old, would be the last to classify himself in such a role. He was not the indoor variety of Christian that practices according to rote and operates within the metes and bounds of prescribed rules. He was the kind that helped a man out of a bog hole, saved a neighbor's cow from bloat, or helped a stricken friend with services and money.

He was a simple, modest man that never spent his time proclaiming his holiness. The God-fearing found him a wholesome companion and the Godless were given a fair hearing.

Like Thomas Jefferson, he had humane democratic instincts. He recognized no caste as superior or interior and granted everyone the right to let his talents flourish. His life was an example of correct living and democratic tolerance. He never cackled over the sins of others or quoted the current tattle about the misbehavings of his friends and neighbors.

He was a solid citizen, but not in the commercialized modern meaning of the term, for he was the kind that keeps a country stable, tied together and growing. His kind symbolizes great mass movements and actions of an era and an epoch. People don't build personal monuments to such men, though well they might; they build monuments to groups of his kind to symbolize events like: Mormon Immigrants Crossing the Plains to Utah: Pony Express Riders: Trail Drivers: Agricultural and Social Advancements. We can live without heroes, but we cannot live without wheel-horses and Hamp was a wheel-horse.

About every constituent in the cells of his body originated in Tooele County soil where he spent most of his life. He and his bride moved into the original rooms of their Grantsville home on Clark Street where they lived until his death on August 3, 1948.

*Hamp was born in Grantsville, Utah, April 21, 1876. His father, Stephen Staley Worthington, was a Mormon pioneer who came from Pennsylvania to Utah along with his parents, James and Rachel Staley Worthington. His great grandfather, Isaac Worthington, was born in England. Hamp's wife, Annie Josephine Johnson, known as Mollie, and Hamp's mother, Joan Eliason, were of pure Swedish immigrant stock. In addition to his father, James Worthington, Grandfather Stephen Staley Worthington pioneered in Utah. Some of Stephen Staley's brothers helped settle the Canadian province of Alberta near the towns of Cardston and Lethbridge. Grandfather Worthington founded a large clan that numbered about 100 living descendents by August 1948.

**Written as a memorial statement by his son-in-law,

B. W. Allred.

Hamp married Anna Josephine Johnson, known as Mollie, October 30, 1902. Their companionable and exemplary life is a story by itself. Mollie was born in Grantsville, Utah, June 12, 1880. She was the eldest child of Charles Johnson and Anna Olson Johnson. Grandfather Johnson was a Utah pioneer from Sweden who had three wives and his living descendents are numerous.

For a man rooted so deeply in Grantsville, Hamp was fairly well traveled. Of course his normal work of livestock raising, farming, brand inspecting, assessing for the county and prospecting gave him opportunity to see the highways and back trails of Tooele and adjacent counties. He probably knew most of the water holes and interlacing coyote trails in Tooele County.

By the time of his marriage, he had seen a lot of western ranges on horseback. On one trip, he visited his Canadian kinfolk. His northward trail led through the Shoshone Indian country of Wyoming and the Blackfoot, Crow and Sioux Indian Reservations of Montana. For days his saddle horses waded north through the wheatgrass expanses between the Yellowstone, Missouri, and Milk River Valleys and over the Sweet Grass Hills along the Canadian and U.S. boundary to the meandering valley of the Saskatchewan.

He punched cows and wrangled horses for a large operator around Las Vegas, Nevada, and in the vicinity of the now Boulder Dam. This was during the Tonopah, Nevada, gold boom. Then Las Vegas was just a spoiling shack and tent town. Freighters loaded at Las Vegas with grub, powder, lumber and tools for Tonopah miners. They drove sturdy high-wheeled, wide-tired wagons with as many as three of them heavily hitched together as a unit. They were pulled by 10 to 16 teams strung out and handled by one man with a jerk line attached to one of the leaders which was a well trained as a circus horse.

Las Vegas perspired with sin like an outpost of Hell. The flapping tent town couldn't house the surplus riot of men that rallied there en route to Nevada gold fields. There were more saloons than any other species of business. Most of the women residents ran or served in brothels, and there was too few of these to service the lusty patrons who wrangled and clawed during the desert night. Stabbings and killings were frequent. The faint ebbing of civilization was still submerged under the overburden of lusty, robust succor growth.

Hamp had an intuition for doing well anything dealing with his agricultural vocations and it was in agriculture that he made his living. However, he had a consuming and unquenched desire to strike pay dirt in a mine. He knew mineral ores and after his death, the family and friends found odd samples of ore from many known ledges in his trousers pockets, on his work bench, in tool boxes and under one bed. During a prospecting expedition, he was as excited as a race horse at the barrier. No one knows how many miles he made on foot and on horseback trying to find the lead from which some high-grade float originated. His old mining pick has pecked at untold outcrops that glistened in the sun and drilled into crusted embankments that might have concealed a vein of ore.

Like many others who had a passion for mining, he never gave up hope that one day he would strike a bonanza. In the family strong box, a tin bread box kept in the clothes closet, a few gilt edged certificates for mining and oil stock was found along with life insurance policies and other family papers. So far as is known, none ever repaid a dull sou on the investments. Life is a gamble and so is mining. It takes faith like his to explore and to find and to maintain an empire. Only a few strikes a rich vein of ore, but those who hit pay dirt also have to have the yearning for minerals and the guts to take a chance just like Hamp did.

Manifestations of his friend's good feeling toward him were displayed in a variety of ways. People liked him and sought him out. At Hamp's funeral, his life-long friend, Bishop Clark, paid Hamp the kind of compliment that would have pleased him most. He said that Hamp was one of the fastest and gentlest hands with cattle that he had ever known. He was a top hand at roping calves and was chosen to do the roping at many roundups. His organization and timing gave him speed and accuracy in roping. He could keep a ground crew of flankers, markers and branders on the hop all day. In a jiffy, he shook the coils of his lariat into a loop, roped a calf, jerked the loop tight, took his dallies to shorten the lasso to manageable length and dragged the bawling calf to the fire where the flankers downed him for branding. Later when age put a kilter in his throwing arm, he did the ear marking and castrating. With his sharp knife in his deft fingers, calves ears were cropped or bitted and bull calves were converted to steers with speed and with as much humanness as can be given in such operations. He seldom charged for these services because he liked to have a chance to keep his hand in the work he liked to do.

Hamp was a friendly man that had time for his friends. His life was not cluttered with the imaginary big things of life. He had time to serve his community, family and friends. He was an easy touch for little boys who needed odd jobs that paid. In the summer of 1947, two little boys bargained with him to weed his side of the street; the price was seventy-five cents. Hamp was not flush with cash and he had the time to do the job himself. However, he said he believed that the few dollars that he paid little boys to do small chores to provide candy money and experience and a small feeling of independence was cheap insurance and might help keep a few from matriculating in reform schools.

A good story teller is a boon to any community and Hamp was a depository of local history. He passed along the word-of-mouth-lore and legends of the county in true Homeric fashion. Once the family let a spare room to tourists in summer and roomers in winter and these he regaled with rich anecdote and colorful incident of the country. Occasionally when he had hooked a greenhorn and had him charmed and covered with goose pimples while recounting some of the harrowing Indian scalping expeditions, he embroidered his yard a little on the windward side in order to keep up the temp of his victim's pulse.

One of his famous windies went like this: "One hundred years ago, when I crossed the desert to California with the Donner Party which died snowbound in the Sierra Nevadas." From there he carried on with obvious exaggerations until his listeners discovered that they were being taken for a hay ride.

There is one local public project that Hamp helped sponsor and keep underway, which too many people fail to recognize as a major enterprise basic to human welfare. That is the Grantsville Soil Conservation District.

Local interest in soil conservation originated in early 1930 when Grantsville was about to become another Antioch. Antioch is the Ancient Assyrian city that became buried in the soil washed and blown from adjacent mismanaged and eroded lands. With monotonous frequency from 1929 to 1935, south winds collected dust from bare farm land and over grazed and burned off range land and peppered the town turning it into a suffocating Hall. Dust clouds rolled through the town and cut off vision; the fine dust filtered through window cracks and door sills then settled in food and finally on to beds where occupants rolled in misery in powdered soil that cut like diamond dust. Grit flitted past in heavy winds and shredded the living vegetation; sand piled up and blocked traffic; sometimes travelers were lost for several hours when caught in the boiling angry drift of a dust storm.

Desperate citizens banded together to fight this destructive agent that had risen up unannounced. They wondered how and why it had developed and what could be done to stamp it out. To correct it, they must know the cause.

The Soil Conservation Service was called in to help control the dust bowl. When the soil, vegetation, climate and past use of the area was checked, the reason for the trouble became obvious. The factors that were essentially responsible for the dust bowl developing had been set in motion as far back as pioneering times. Drought merely kicked it off with greater speed and menace. Scalped of the protective soil cover, nature was merely in rebellion and dust was given in retribution for man's mismanagement. The chronology of the developing dust bowl was part and a big part, of the local history that man had missed. He was more concerned about vital statistics of the human race and gee-gaws and gadgets than he was for his natural resources. The events that lead to the development of the dust bowl were strong out over a long time. The cause of the dust bowl was about as follows: livestock over used the native wheat grasses, blue grasses, Indian rice grass and other nutritious herbs. These good plants died or thinned out and the sparse sagebrush and other shrubs took possession and thickened into dense scrub forests. These shrubs are fairly edible and nutritious part of the year and animals survived when they were given supplements in winter. Brouse plants are not as good soil conservation plants as well managed grass, but they held off the wine and held down a good deal of water erosion.

Sometime before 1920, cheat grass, (Bromous tectorum) a winter growing annual from the Mediterranean regions, spread through the intermountain region where it became naturalized, and grew companionable with sagebrush where the good native grass had been grazed out. Cheat grass is nutritious when green and livestock fatten on it when they have plenty of it. It matures in May or June and turns to the color of a faded palomino horse hair. Dry cheat grass flames actively when fired. On good years, it provides continuous tinder on Grantsville ranges.

Years ago fires broke out and large areas of big sagebrush burned to the crown and died. Sage comes back slowly and that gave cheat grass almost exclusive control of the land. Early in 1930, over grazing and fire took off the cheat grass cover. When the south winds caught several square miles of ground bare, the unprotected top soil was blasted loose and Grantsville was on its way to becoming another Antioch. Dust storms scourged the country as vengefully as an ancient Passover.

There was only one way to dispel the erosion curse, all agreed, and that was to help nature grow back her magic carpet of protective vegetation. Since the problem was a local one, Grantsville land owners elected their own committee to cope with the problem.

They requested and use the technical assistance of the Soil Conservation Service range men, engineers and agronomists. The local land owner committee started the emergency soil conservation work. By 1937, Utah had passed its State Soil Conservation Act and in October of that year, the landowners voted for the Grantsville Soil Conservation District, which assumed local leadership and action for soil conservation work on the dust bowl and on the farms and the ranches of Tooele Valley land owners who asked for assistance.

These men harnessed the dust bowl and subdued it with grass. They gave the vegetation needful rests and lenient use until the bare ground healed with grass. Thousands of acres of crested what grass and other nutritious forage plants were seeded and their roots, leaves and stems held the land secure and the forage now supports the equivalent of 600 animal units of grazing per year. It is improving at a yearly rate which will out yield the present stocking figure.

This self-liquidating project took a lot of local initiative to engineer. The original local erosion committee and finally the five elected soil conservation district supervisors gave freely of their own time without recompense except that of seeing their community saved from the extinction because of erosion.

Hamp, with several of his friends, were largely responsible for originating and maintaining this fine job that kept Grantsville from becoming buried in sand drifts. He was elected for many assignments where the public was benefited because he was progressive, had an open ear and had sound judgment.

When a needful public job with no pay came along, busy-minded local people would say "get Hamp to do it, he has the time." Actually, Hamp had no more spare time than others. But he was unique. He was a friendly man who had time for his friends.

Family Members

-

![]()

Cecilia Worthington McHattie

1868–1944

-

![]()

Sarah Worthington Wagner

1870–1961

-

![]()

Rachel Augusta Worthington Anderson

1872–1936

-

![]()

Birdie Eliza Worthington Anderson

1874–1956

-

![]()

James Stanley Worthington

1878–1960

-

![]()

Frederick G Worthington

1880–1890

-

![]()

Phoebe Staley Worthington Bills

1883–1973

-

![]()

Charles Homer Worthington

1885–1972

-

![]()

Samuel Hilton Worthington

1888–1971