Mom loved her daughter-in-law Sue like a daughter and said that although her daughters had very good characters, Sue's character was even greater, stronger and special than their's. (Her daughter Joan derived a degree of national notoriety during the 1980s for her selflessness and self-sacrifice). Sue's character comes from her Sullivan and Slack roots.

After they met at Stuttgart, Arkansas, Mom noticed that Dad, known in the army as "Andy", had a small box clipped to the inside of his army shirt but wouldn't tell her what it was or let her see it. Finally she playfully grabbed it and noticed that it was an engagement ring. Mom then told him that she didn't think there was any way that they could marry (especially after having just met his family), but he said just wear it. The next day she was called into Col. Ryan's office, the head of her outfit and head surgeon. He immediately commented on the ring on her finger and she said, "yes, Andy." He immediately lifted up papers on his desk and ripped them in two. They were orders reassigning Mom to the Pacific where she had wanted to go to be closer to treatment of the wounded there.

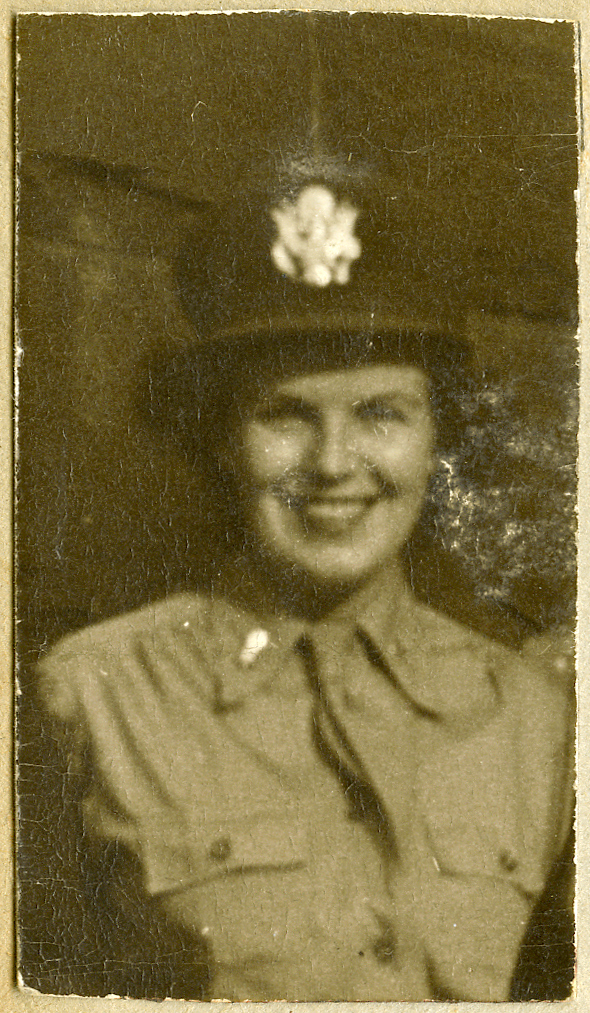

Mom enrolled at the University of Detroit in 1937 and St. Joseph Hospital, Hamtramck, Michigan in September, 1939, receiving an R.N. Degree in 1943, and entering the army shortly thereafter.

Mom has a deep faith like her father and is completely selfless and kind. She is also strikingly beautiful. When she was little her siblings could not pronounce her name and they called her "Bitte Nine" rather than Betty Jane. At age 6, Mom was struck by a car as she chased a ball into a street in Detroit near Grand River and West Grand Boulevard and she was taken to Providence Hospital in Detroit with a broken leg. Her father successfully tracked down the driver and called him simply to let him know that he knew he had hit his daughter.

In her early years of grade school, a little girl in school always made derrogatory comments to others, watched Mom play the piano while she was taking lessons and commented that she had the ugliest hands she had ever seen. Mom never again played the piano.

The family moved to Monica Street in Detroit when Mom was 9 or 10. Twenty years later or so, her parents moved to 2850 Oakman Boulevard in Detroit the day she returned home from the hospital after her first child Bill was born in 1945. Mom's brother Uncle Ted had not yet returned home from the war in Europe.

Earlier, Mom's father planned to put money into the construction of a building for his company, Michigan Drilling Company, and came home to find his wife, Jessica, who we called "Ganger", had been crying. He told her then and there that the house on Oakman Boulevard was her's and he did not build the building for Michigan Drilling Company.

Mom attended St. Bridget Grade School and was taught by the Dominican nuns. She then attended St. Cecilia's High School at Grand River and Livernois in Detroit and the University of Detroit from 1937 to 1939, the most wonderful years of her life under the Jesuits. She met, and developed a strong friendship with, Otto Winzen and his family while at the Universtty of Detroit. They had escaped Germany just before World War II. (Bill Andrews was taught at St. Louis University by the former President and Chancellor of Austria, Kurk von Schuschnigg, whom Hitler had jailed. Upon Von Schuznick's invitation, Bill visited him in Austria after Von Schuschnigg retired from St. Louis University.) Otto and his wife in the late 1950s visited the Andrews family farm in Tennessee on their return to their home in Minnesota after a stratospheric balloon liftoff in Florida. Otto produced the scientific balloons that preceded Alan Shepard's flight and the space program. Otto's father was the Henry Ford of Germany. Mom's teacher and friend at the University of Detroit, Father Kuhn, said that everyone in Germany knowns Otto's father, Christian Otto Winzen, just as everyone here knows Henry Ford. Otto's mother, Lily Winzen was the sister of Franz von Papen, Chancellor and Prime Minister of Germany before Hitler. Lily Winson loved Mom, saying that Mom "looks like an Angel." Otto's brother, Hans Winzen was president of Buick Motor Company and came up with the advertizing slogan. "Better Buy a Buick." Otto's wife, Maryanne, was very religious and was being treated for cancer at the time they visited the farm in Lewisburg. They were very much in love. While at the University of Detroit, Mom also knew Roy Chapin (whose father was President of Packard Motor Company) who became President of American Motor Company.

Mom's comments about her college friend, Otto Winzen:

I was good at languages for some reason. In high school, in Latin, every year I would get an "A" because I loved languages. French, in St. Teresa's High School and in St. Cecilia's Latin. In first and second year Latin I always got an "A". I loved languages. At the University of Detroit, Spanish. Dr. Espenosa who I had at U of D said he could not believe it. He said I sat down correcting this one exam and every single answer was exactly right just as if I was copying it from the book. Spanish, Latin, French, even Italian, everything. I never took German but Otto Winzen always called me "shahtzi". I went to a German movie with subscripts and finally learned what that meant. I remember I went to a Legion of Mary breakfast and Otto came up and talked to me. And he got up to give this talk. And he said well Hitler this and that. And then he said, wait a minute. No, this is the way it is. There's not a convent standing in Germany now. And he knew he was on dangerous ground in America because people weren't getting out of Germany except through his uncle, Franz von Papen. Father Kuhn told me every man in Germany and Barvaria knows the name Christian Otto Winzen. He was the Henry Ford of Germany. His invention was the Volkswagen. Smaller and smaller and hardly any gasoline was used in it and took very little of the battery.

Otto's mother Lillie Winzen and I loved each other very much. Her brother was prime minister, von Papen. She was Lillie von Papen [but official records have her maiden name as Lillie Lerche]. Otto never bragged. He never talked about the fact that his mother was the sister of Von Poppen, the former Chancellor of Germany. Every time I'd bump into her, she'd be coming out of the convent, Mary Reporatrix, and I'd be going in.

Otto's wife Maryann was the most beautiful girl I think I've ever seen and the most wonderful Catholic. Otto was the most deeply religious person I have ever met and his wife Marion said, "the most spiritual." Otto took Marion to Oconto, Wisconsin to see Dr. Patrick O'keefe's (Betty's grandfather) residence and offices.

Otto said that his father told him never join any German club when you get to America, like the Bund. The German Bund had looked Otto up. Otto was politically naive and he joined this organization backed by the Bund and meet Vera there, who was not Catholic but German Luthern. Anyway, Otto did get a job through them and invited me to go to an evening social in a park one night sponsored by the Bund. The Bund met in the General Motors building across from the Fisher building in Detroit and I never went to anything other than this social which was in a park closeby. I met Vera, maybe not that night, but I did meet her. Otto called me one day. He said "Betty I have the most wonderful news." He said "could you ever come downtown. Just get on the bus and stay 'til the end of the line." So I got on the bus and the name of this place in Detroit is called Grand Circus Park where the buses all end. And he came up and grabbed my hand and he said, "I want to show you something." And he opened his wallet and pulled out a check. He said, "I've got a job." I don't know how much it was, but many thousands. He said, this is my first paycheck. He said, "I was so excited I couldn't come out to the house. I had to have you come here." He didn't know it but it was from the Bund; he was unknowingly employed by the Bund. It was so much he dared not leave until putting it in the bank.

And then I went into nursing and entered the Army as a nurse and didn't see Otto. He was put in as an American Prisoner of War and I lost track of, and I didn't see him. I'm getting into so many things… but anyway, America made him a prisoner of War and it saved his life. After I was in nursing, the FBI looked Otto up because of his membership in the Bund and put him in a concentration camp in Minnesota I think during World War II. Otto was transferred to a prison camp in Arkansas I think. The FBI questioned me about Otto.

Otto, when he came to our house at the farm, remember, he had the world's highest altitude record that night. After his visit to the farm he phoned me on my birthday [He remembers my birthday from the early days at U of D] and he told me he was up in a balloon and it crashed. It's hard to explain. Otto then told me that "if you hear that I died by suicide or accident, it will be neither."

Otto was the deepest Catholic. When a German has faith, it's very deep. And he knew the whole story as soon as he crashed and got back.

Mom left the University of Detroit before beginning her junior year in September of 1939. She went to the University to register, but later that same day registered for a nursing program at Mt. Carmel Mercy Hospital in Detroit instead. She left the University of Detroit because of the pressures of being very popular (elected queen of many balls and asked out very often). She received her RN degree in June 1943 and went into the Army just before Christmas of 1943 as a Second Lieutenant. She was sent to Montgomery Field, Alabama for basic training and then to Stuttgart Army Air Force Base in Arkansas in January 1944, where she met Dad, a First Lieutenant and Medical Supply Officer. They met while she was looking for the Army Post Office on base to send a letter home, and he saw her wandering around unable to find it. She then went up to solders who were German prisoners of war who did not understand her. Another officer came up and told her that they were German prisoners. Just at that moment that officer hailed an Army ambulance, which had her future husband in it, to take her to the Post Office. Dad introduced himself and, that night in pouring rain, went over to the base hospital and told Mom that he had some nice records that he wanted her to hear.

Later while Mom was on call for surgery, she and Dad went bicycling and saw a plane come straight down and hit the ground. After sounding the hospital alarm, they headed toward the plane and another alarm sounded. When they got there, four boys were sitting safely on the wings smiling as the ambulance drove up.

Dad successfully represented a soldier in a court marshall proceeding after the soldier took a plane home to visit his parents. Dad, as a lawyer, is not aggressive and that helped with the jury (officers on jury) according to Mom.

Mom and Dad met in January 1944, he proposed to her on May 1, 1944 at the nurses quarters and they were married on Saturday, November 25, 1944. Her father, Edward J. Early ("Gampa"), her mother, Ganger and her sister Joan (her brother Ted was flying in Europe), Dad's mother Stella Simpson ("Grandmother") and his sister, Aunt Sara, attended the wedding at the Army Air Force Chapel. They were married by Fr. Thomas Evans. Lt. Emil Mascha of New York was best man. They honeymooned at the King Cotton Hotel in Memphis, Tennessee for two days and then on to Nashville to visit Dad's family. Then both returned to Stuttgart. Mom stayed in the service until June, 1945 at which time she left because she was expecting William Lafayette Andrews, III, (Bill) (his name was changed to William Xavier Andrews later in life). Mom then returned home to Detroit when her husband was transferred to Alexandria, Louisana for four months, after which he was discharged as a Captain. Dad then came to Detroit where Bill, was born.

The family settled on Stokes Lane in Nashville, moved to Atlanta in 1950, Mom and the children left Atlanta for Detroit in January 1951, and then left Detroit for the Lewisburg, Tennessee farm in August 1953. Gampa bought a vacation lake house for her in Canada during her stay in Detroit and son John recalls one cold winter night leaving Lake House for Detroit with Bill in Gampa's car and their sisters, Joan and Susan, following with their mother in the "Old Grey Mare" as they called their car. Just after leaving Lake house and making the elbow turn at the river flowing into Lake Saint Claire, John looked back and noticed the headlights of the Old Grey Mare going on and off and the car did not seem to be moving. Gampa turned around and found that the Old Grey Mare had slid off of the road at the elbow turn and landed upside down on the ice covering the river. Gampa pulled everyone from the car safely.

John remembers his mother as a most loving, selfless and saintly person. She would do anything for others. When the family first moved to the farm in Lewisburg, Tennessee, she immediately had electricity put into the tenant house of Sally and Milton Evans, her husband's sharecroppers with twelve children. (Kenneth and Conslo Andrews, Dad's uncle and aunt, had lived in that house when they were first married and it was known as the oldest house in Marshall County. Mom had it torn down in 1972 and the hand-hued logs transported to the Old Hillsboro farm so that the wood could be used by Roy Wakefield of Lewisburg to add a room to the house there.) She regretted that she could not supply water to the house to save the Evans family the difficulty of having to carry buckets of water the eighth of a mile or so from the main farm house to their house. Mom recalls that in the dark of her first morning on the farm she was sound asleep when she heard Milton say loudly, "Good Morning, Mr. William!" after finishing his milking. Of their 12 children, Harvey Evans, who was 15 when the Andrews family moved to the farm, with his father, Milton, milked the Andrews' cows and did the other farm work. Harvey's twin brother, Howard, would help every now and then. Milton had worked for the railroad, but worked at the steel foundry in Lewisburg, owned by the Weaver family with whom the Andrews family attended mass, during the time the Andrews family lived on the farm. Dad and Milton split the profits from the sale of milk to compensate Harvey and Milton for their work. Harvey would get into trouble periodically and Dad would bail him out of jail. In the mid to late 1950s, men from town apparently followed the Evens boys home from a Saturday night out on the town and a fight broke out at their house. Dad woke up, went upstairs, got a machete, and stood between the Evans house and the farm house waiting. The police then came and broke things up. Milton died in 1965 when Bill and John were in their first year at St. Louis University and this affected John quite a bit because he missed the farm including the Evans family so much. After Milton died, the Evans family moved into a government housing project in Lewisburg. Every evening for a long time after Milton's death, Harvey could be seen sitting in a rocking chair on the front porch of the empty house he had lived in on the farm, rocking back and forth gazing off into the distance. Then all of a sudden he no longer returned.

Another example of Mom's extreme selflessness and kindness is that she was kind to her in-laws although they appeared to hate Catholics passionately and to hate her in particular, constantly ridiculing Catholics and their mother when speaking to her children. In her eighties beginning in the mid-1990s, Mom prepared meals for Aunt Sara and took care of her when she moved in with Mom and Dad on the farm after she was unable to care for herself alone in Nashville. Joan and Susan, recall their Aunt Sara telling them when they were in first grade that their mother had died at sea during her trip to Rome with Ganger in 1955 for the canonization of Pope Pius X. The children recall their father having to take all scapulars and all religious articles from them and brief them on what not to say before visiting their Aunt Sara and Grandmother.

In the early 1950s when our family attended Mass at a vacant drive-in theater building on the Nashville highway in Lewisburg, Betty wanted to donate a piece of land at the corner of the farm to the church so that the new Catholic Church could be built there, but her husband's family was opposed to that.

Betty, always very energetic, was constantly attempting to improve the farm house, most of the time to her husband's dismay. She tore one set of walls out of the hallway leading to the bathroom between the kitchen and the bedrooms. She built new closets between the girls and boys bedrooms and put holes in the shape of crosses in the back walls of each closet for the evening Rosaries. (She would sit in the closet on alternate nights in one bedroom and then the next night in the other saying the Rosary with the children. Their father, not being a Catholic, did not join them.) She moved all of the out-buildings, such as the chicken coup which Uncle Bascum had built years earlier, the tool shed and the log cabin, away from the house.

Betty's primary concern in life was instilling a strong faith and love of God in her children, teaching them kindness toward others, even those who might have harmed them, teaching them never to touch a drop of alcohol and the importance of purity even to the point of giving up life rather than being impure.

The children's education was also very important to her. In first grade she would sit with them going over their reading lessons. She constantly corrected their spoken English and drilled them in geography and other subjects. During the summers she would work with the children on their studies so they could either catch up or get ahead.

When with boys were studying to be alter-boys in second grade, she drilled them night after night in their Latin. When the children were in Belfast Elementary School she had each of them take piano lessons and made sure they practiced an hour each day. Bill, Joan and Susan took lessons for a year and John for two years.

When John started high school, he and Bill (who had spent his first year of high school at Marshall County High School) enrolled at Father Ryan High School in Nashville. They lived at a boarding house, Blair House, in Nashville near St. Thomas Hospital the first semester and first half of the second semester, which was just a few blocks from Father Ryan. This was very difficult. The boys recall having a 25 cent tuna sandwich for lunch each day and 5 cent Crystal hamburgers for dinner.

Their Aunt Sara visited them at the boarding house early the second semester and brought bananas. (John recalls them gobbling them up they were so hungry.) Then by Spring their grandmother and Aunt Sara allowed the boys to stay at their house at 4110 Lealand Lane in Nashville. John recalls telling his mother that he would prefer not going to Father Ryan that next year, but he changed his mind later.

He recalls going out into the woods on the farm on Sunday afternoons before returning to Nashville with Louise Gillespie and sitting in a tree to ponder and soak up the farm before leaving. The next school year, Betty and all of the children except Joan moved to the house Betty's mother had given her at 1003 Tyne Boulevand in Nashville. Joan elected to stay with her father in Lewisburg while he continued teaching at Belfast. Then the following year, Betty's husband left the farm and his job in Belfast and moved to Nashville with the rest of the family. The first year he renewed his teaching credentials by taking courses at Peabody College and then began teaching at Lipcomb School on Concord Road in Brentwood.

When John bought the farm in Williamson County in 1972 with a partial loan from his mother from the proceeds from the sale of the Tyne house, her husband retired from teaching at age 52 and the family moved back to the Lewisburg farm. After not having worked as a nurse for twenty or so years, Betty then returned to nursing, initially working at nursing homes and then at Lewisburg Community Hospital on Ellington Parkway near the farm.

Her husband, William L. Andrews, Jr., loved the farm as did she and the children. He spent every summer on that farm with his cousin Paul Harris after his father had died in 1925, when he was 8. Because of his love of the farm, he did not want the children to grow too attached to Nashville by going to social activities at school, etc. during their high school years.

During the years they lived in Nashville, the children loved spending every weekend and every summer on the farm. Elizabeth's son John: "My mother is a very strong and fervent Catholic and was dominant in the home. She instilled very strong morals and values in her children, made enormous sacrifices for them and attempted to protect them from harmful influences. These influences included those coming from my father who had a love of philosophy and whose philosophical ideas were adverse to those of my mother. She feared that my father's ideas would draw the children away from the Catholic faith.

My father was brought up in the Methodist faith and found it lacking. At the time my parents met during World War II, he was not practicing any faith. He appeared to be a deist with a very strong love of God. My father is very kind and loving, yet because his father died when he was only 8 and his mother and sister, who was 8 years his senior, were very domineering, he is a reserved person. He has extremely high morals and intelligence, and I feel very close to him as I do my mother.

Because of my father's beliefs and the interference of his mother and sister in the life of our family, my mother left my father for three years when I was between the ages of 3 and 6 years. When they reunited, there continued to be difficulty over religion despite my father going to Mass with us each and every Sunday. The difficulty, however, was very tame compared to that before their separation. The friction dissipated completely when my father became a Catholic to our surprise within a few years after I graduated from college.

My brothers and sisters and I were very close throughout childhood and are close today. My brother Bill and I were almost inseparable growing up and through college and I introduced him to his wife. He volunteered to serve in Viet Nam to prevent me from having to serve upon finding that I had orders.

I have from early childhood admired, and been in awe of, my sister Joan's unwavering convictions, self sacrifice, kindness and strength of character. My sister Susan and I had a few difficulties during childhood and later in adulthood. The childhood difficulties resulted because I thought Susan was too pretty and feminine, and, as a child, I wanted Susan to be a tom-boy. The later difficulty came because I disapproved of some of those Susan dated and because I did not give Susan enough credit for having the ability to make the right decisions in life. Susan and I are very close today, and I love her very much as I do my sister Miriam and my brother David."

The first time John felt close to his father was during his sophomore year of college at Saint Louis University in 1966. Just days after the start of the semester, at 5:00 one Saturday morning, his father knocked on the door to the dorm room he shared with Bill to tell John he had received an Army draft notice. He had traveled all night via train, derailing outside of St. Louis. When Dad left, John's eyes welled up with more emotion than he had ever felt for his father, as John waved goodbye to him as he viewed him through the back window of his taxi. This trip would have been something formulated and encouraged by Mom.

The Andrews family did not have a car for a period of time after the break-down of the Packard car that Gampa had given them for their trip from Detroit to move to the farm in August 1953. A few years later after owning their own cars, their Uncle Ted gave them his car for a trip back to Tennessee after summer vacation in Detroit. Mom sold her wedding and engagement rings to purchase school books for Bill and John, who were starting first grade at St. Catherine's School in Columbia, Tennessee. Dad did not work the first year the family was on the farm, and did not work after leaving Atlanta some years earlier. The family did not have regular meals and were nurished primarily by milk fresh from the cows on the farm, honey toast and popcorn. The milk was warm with thick cream on the top that Mom stirred into it with a raw eggs each morning before school and then the children took a jug of milk to school everyday as their only lunch food, Chairs March, a year older that John, cleaning the jug every day for them of his own volition. The children never lacked nurishment and they, especially John, loved the farm life they were lucky enough to live.

John recalls arriving at the farm just after dark in August 1953 and all of the children going from shed to shed surrounding the house, looking at the chickens in the chicken coups, etc. It was so exciting. The next morning, the children got up early and went first to the "Island Field" where they saw fifty or more sheep grazing. John loved farming more than the rest of the children and, athough his mother did not want the children's childhood spoiled by having to toil on the farm, he would periodically get up at 4:00 in the morning when he saw Sally and Milton's kerosine lamp go on before they had electricity and help Milton and Harvey milk. John also loved to plant a garden each year and plow and mow the fields. The children had to leave for school between 5:00 and 6:00 in the morning since there were no paved roads between Lewisburg and Columbia. John can remember throwing-up frequently in the mornings at one particular spot in the road just before getting into Columbia. For a period Bill and John rode into Columbia with Bit Hardison in his delivery van while he picked up eggs at farms along the way. Their first year on the farm, their father would wait in Columbia until the boys, who were in first grade together, got out of school and then drive them home. When the boys started second grade and Joan and Susan first grade, their father began teaching at Santa Fe School, thirteen or so miles north-west of Columbia.

When John was seven, he woke up after about an hour of sleep in the early fall of the year unable to control his crying after he had strong feelings about being all alone someday without his parents and family. Mom took him out into the front lawn, joined by Dad, and they sat with him attempting to give him solace.

Dad loved the farm as did she and the children. He spent every summer on that farm with his cousin Paul Harris after his father died in 1924, when he was eight years old. Because of his love of the farm, he did not want the children to grow too attached to Nashville by going to social activities at school, etc. during their high school years. During these years, the children loved spending every weekend and every summer on the farm.

INTERVIEW WITH MOM DECEMBER 15, 2012:

My sister Joan, my dear sister Joan, the dearest soul in the world, and she had it very, very hard. From the time she was born she was very weak, so when it got time for school, she went to St. Bridget's, and the local schools - St. Bridget's and St. Cecilia, so when it got time that she would naturally go to college, they sent her to a Catholic, very expensive school in Canada in, the first town in Canada after you cross, we didn't go under the tunnel, after you go across the Ambassador Bridge; Assumption. My father took borings to take footings for the Ambassador Bridge and the Tunnel. But anyway, they had my sister go to school there. I think it was – I think they called it Assumption. It was all girls and the girls were taught by French nuns, and they were taught very proper behavior. They used to call them finishing schools for wealthy girls. She didn't go to college. She went to this Assumption. May I tell you this? My mother, and I even I must say, and my grandmother and my Aunt Gertrude, they favored me over my dear sister Joan. She's the dearest girl in the world. And I was too dumb to see. I loved my sister but my mother would say at night, let's take a walk. I should have, I was too dumb to realize, why doesn't she take my sister Joan. I really mean that. I just loved everybody and I just didn't think there was such a thing, know there was such a thing as favoring. And when my mother said do you want to take a walk with me, everything my mother said was gospel to me and I just couldn't think for myself. My mother would say, Betty, let's take a walk and she'd buy me an ice cream cone. My mother took me for a walk, so that was it. It was strange. Everything my mother said is what I did. My first summer vacation at U of D my mother took me to Wisconsin with her and my mother thought my father's family, the Earlys, were just second class. My mother - I'm telling you as it is now - I never heard my mother say anything nice about my father. She wasn't bad to him. At dinner he would say all I'd like is a glass of water with the meal. I never heard her say, oh, put a glass of water at your father's place. I just can't explain it. But I never remember her saying anything good about my father. My father had a very lonely home life. He belonged; Daddy was deeply religious, deeply fervent. He was a third order Franciscan. When he died he was buried in his suit and some Dun Scotis priest came to the house and they brought a Franciscan robe. It wasn't put on my father. He didn't know that. And I said that's very good of you. And he said, I'd do anything in this world for that man. That's the way people felt about my father. My mother put it in the coffin, but not in a place you'd see.

LETTER FROM BETTY EARLY TO HER FUTURE HUSBAND:

Postage

Free

Lt. Betty J. Early

A.N.C. N-790172

Stuttgart, Ark. SAAF

July 4, 1944

____________________

13637 Monica Ave.

Detroit 4, Mich.

Lt. William L. Andrews 01533246

Sec. E. 2141 1st AAF Base Unit

SAAF Stuttgart, Arkansas

Monday

July 3

13637 Monica

Detroit

Dearest Andy --

Here is a setting of music ("Now I Know") and everything nice. I'll have a visit with you. All morning we've had beautiful music. I woke up with the strains of "I'll get by" from the radio in Joan's bedroom. Then we all came down for breakfast at 9:15 am and Joan had orange juice ready for us, and we turned on the radio downstairs.

We left on the train about 7:00 pm Friday night. I took some pictures of Ruth Habig and Wanda before leaving. There were quite a few people at the station leaving on that train and it seemed that everybody knew everybody else. I saw the Haytes there at the station. There was much excitement and the station manager came out and carried the baggage to our train! I bunked in with Ruth from Stuttgart to St. Louis, and we got into St. Louis about 9:00 am. The train for Detroit left St. Louis about 9:15 am, and it got to Detroit about 11:30 pm! (St. Louis was the only change.) Mother, Dad, and Joan were at the station! Golly, it was wonderful! The station was just packed and Joan was the first one that I saw. She was in a sweet orchid suit. We got home and had chicken a la king. And there were candles on the table and flowers in the house and music! We talked around the table until after 2:00 am. The house just looked like a jewel box! It just thrilled me to see the lights from the French windows shining through the trees as we drove up. Then the front door and the knocker, and the moon shinning down on the house! And inside! .......the living room in mulberry and moss green! And the dining room with the roses and candles and table set with the mulberry luncheon set! It just seems to me I never deserved all this. Mother and Dad gave Ray and Joan a beautiful dining room set that they're keeping packed in the basement and Joan showed me the pictures of Ray she had gotten, and they're both wonderful, both the smiling and serious one! Not a thing was changed in the bedroom. It is so grand to wake up in the morning and look around to the sky blue ceiling and soft rose walls and pretty little bedroom that I love!

Yesterday morning we went to 12 noon Mass at Gesu. Then we had dinner about 2:00 pm and visited. We took some pictures which I'll send to you Thursday, Andy. Joan continually asks me about you, Andy -- I wish you were here! The silver fruit basket is kept filled with fruit -- oranges, bananas, plums, green grapes, and big dark sweet cherries!

Joan is writing Ray right now and Mother is writing Ted and I'm writing to Andy darling. Ray is in Las Vegas, Nevada for this coming month. Ted has a new assignment and is in Spaghetti country. He said "all hell has broken loose" over there.

With the radio going all the time, I think of you more than ever, Andy. "I'll be Seeing You" - "Would you Rather be a Mule," etc. Have you heard "I found You in a Dream," Andy?

Frank Davner happened to phone yesterday and explained to Joan that he wanted to be a brother to me. I could see the new Officer's club at Romulus tonight, but I' not, Andy.

Your letter just came, Andy, and I was so happy to get it. Yes, I was so sorry that I did not go down to the train with you. As we stated off in the car I said to Ruth, "I wish Andy were in the car here." Several times on the train I almost said aloud to myself "I wish you were along."

I'm so glad to be home, I don't know how to act.

Well, Andy. Good bye, hasta la vista. Right now I'm eating a plum! Yummy it's good! Chew, Chew, lick, lick, smack!

Good bye again, Honey bunny, and don't work too hard.

Yours, Betty

Granddaughter Elizabeth Andrews:

Although there have been many experiences in my life that have encouraged and inspired me to pursue a career in nursing, the most memorable and impactful experience was one I shared with my grandmother. She loved to share stories with us and I was always captivated by her stories about her work as a nurse, both in the army during World War II and in civilian life. Through her, I began to see the life changing roles nurses play within the lives of their patients. Being a deeply compassionate person, my grandmother loved to care for the dying, especially those who had no family. She felt a responsibility to be there for those close to death to bring them reassurance and comfort. Not only did she care for her patients' physical needs, but for their emotional needs as well. She loved to get to know her patients and to spend time with them. She recognized the dignity and value of her patients regardless of their background and went out of her way to make them feel cared for. Hearing her speak of the different ways she brought meaning and joy into the lives of her patients instilled in me a desire to help people just as she had with cheerfulness and joy.

Some of my academic accomplishments include being on the President's List at Cecil College with a 4.0 GPA and also becoming a member of the Phi Theta Kappa Honor Society in 2015. I also received two awards for National History Day, including one for Ethical Issues in History. Additionally, through my diocese in 2015, I received the St. Timothy National Award for Outstanding Young People. Some of my interests include reading, sports (I very much enjoyed the intramural sports at Franciscan!), hiking and other outdoor activities. I also love being involved in my parish youth group and respect life group. I also hope to gain experience working in a hospital or nursing home this coming semester.

"THE ARROWHEAD FIELD" BY SON BILL:

Where my dad is laid back and soft spoken, Mom is a firecracker, a body constantly in motion whose outspoken candor and hardheadedness are perceived by many southerners as emblematic of Yankee assertiveness.

In 1918 Gampa was serving in France as a captain in army ordnance when Ganger gave birth to my mother, Betty Jane Early. Mom was born in Washington DC, during the opening phase of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive that ended the Great War. Reunited at war's end and anticipating economic opportunities in the bourgeoning automobile Mecca of southeast Michigan, Gampa and Ganger moved their young family from Green Bay to Detroit. There my grandfather founded the Michigan Drilling Company, an engineering firm that drilled and analyzed core soil samples to determine foundation strengths for the skyscrapers being built during the boom years of the Roaring Twenties. Gampa's rigorous work ethic built wealth for his family and his savvy investment sense spared him the great economic losses visited on so many other families during the depression.

During the late 1930's, Uncle Ted and Mom attended the University of Detroit, a Jesuit institution similar to Gampa's alma mater. Uncle Ted followed in Gampa's engineering footsteps and Mom majored in the liberal arts as had her mother... Mom was enjoying an active social life at U of D where she was a popular coed, a class officer, and a sorority sister in --- ---. Twice her peers elected her Snowball Queen for the university's biggest social gala. In old black and white photos and newspaper clippings collected by Ganger, Mom is always shown with a coterie of young men flocking about. In these time-capsule portraitures, she reminds me of Vivian Leigh's rendition of Scarlett O'Hara in the opening scenes of Gone with the Wind, with potential beaus flittering around her, solicitous to the point of sycophancy. One of Mom's beaus was Otto Winzen, an anti-Nazi German student who remained in the United States during the war, became an American citizen, and later gained renown as the inventor of high altitude balloons for scientific exploration of the ionosphere.

In September of 1939 when World War II erupted in Europe, Mom was enjoying an active social life at UD and Dad was in law school at Vanderbilt. A year later, as part of a preparedness program, Franklin Roosevelt inaugurated the first peacetime draft in American History and Dad was the first young man conscripted from Vanderbilt. The army permitted him to finish out the academic year before entering military service. He was one year shy of finishing law school when he entered the army.

Unlike many of their generation, neither of my parents was much affected in the quality of their lives by the Great Depression. It was Pearl Harbor that transformed frivolous and carefree youngsters into serious and responsible adults. Uncle Ted, Mom's brother, joined the Army Air Corps and after training piloted a B-24 Mitchell bomber in the European Theatre. He fell for an English girl, Katherine Thomas, and named his plane "Kate." Eventually he married her and brought her back to Detroit where my grandmother, long an aficionada of English manners and customs, treated her like royalty. Mom dropped out of the University of Detroit at the end of the spring semester in 1942 and entered St. Joseph Hospital's nursing school where enrollment soared due to the war's demand for medical personnel. She was recruited by the army at her graduation in the summer of 1943 and began basic training at Montgomery Field in Alabama in January of 1944. Her first duty assignment in March of 1944 was to the main hospital at Stutgartt Army Air Corps Base in Arkansas' rice and duck hunting country.

The 1940 draft that snared my dad was the first peacetime draft in the nation's history. It was a war preparation measure because things looked so bleak for England. The Battle of Britain was not going well and England was running out of funds to pay for the Cash and Carry provisions of the 1939 US Neutrality Act. At the time Dad got his draft notice, Roosevelt was running for an unprecedented third term on a platform that called for loaning England our planes and tanks. To promote his Lend-Lease program, Roosevelt used the example of the neighbor asking to use the fire hose. Dad was inducted into the army on 16 July 1941, one year shy of graduating from law school and five months prior to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Mom was still a college student in Detroit when Dad entered the service. He received his basic training at Camp Lee, Virginia, and advanced training at Camp Barkley near the Texas town of Abilene. In mid 1942 he was sent to Carlisle Barracks in Pennsylvania for Officer Candidate School where he received his commission as an officer in medical administration. After a brief stint at the military hospital in Columbus, Ohio, Dad was transferred to Stuttgart Army Airfield in Arkansas where he spent most of the remainder of the war. However, in late 1943 he applied to aviation school and was sent on temporary duty to an airfield near the Davis Mountains of southern Texas to learn to pilot an aircraft. He trained in an old Fairchild biplane and was already flying solo when he experienced a near collision one day. The incident occurred when he was on a flight with an instructor whose job it was to certify him. Dad was in the front seat of the cockpit when he saw an approaching aircraft ahead of him. In the confusing sounds of rushing winds swirling around the open cockpit, the instructor yelled or signaled to Dad in a way to suggest that he was taking the controls. Apparently the teacher didn't see the plane and thought Dad had the controls. It was a near miss and such a traumatic moment for Dad that he washed out and, to this day, flies infrequently. In fact, over the past sixty-two years, Dad has only flown three times as a passenger on a commercial aircraft and then only with white knuckles gripping the armrest. I find it interesting to speculate that if my father had not washed out in February of 1944, he never would have returned to Stuttgart to meet my mother and to father the child who would be I.

Back in Arkansas doing medical administrative work, he was called upon once to assist in a special court martial case where he had to work as an assistant defense council for a homesick soldier who had gotten drunk and stolen a plane for a flight home. Although not a pilot, the young man took the plane up and actually manage to land it without much damage. It was a cut and dried case with a sentence of about six months in the brig. Because Dad was within a year of graduating from law school, officers in the judge advocate division prevailed upon him to help in the case.

It was at Stuttgart that my parents met in the spring of 1944 when Mom was assigned to the post hospital as [chief] surgical nurse caring for the medical needs of young soldiers wounded in the Pacific Theatre. They met under circumstances not uncommon for men and women far from home in the midst of a global war. On the evening of her arrival at Stuttgart, she ate with the other base nurses in the Officer's mess where she was introduced to Dad and the other male officers at the hospital. The next day after work, she was walking around the base looking for the post office where she planned to mail letters home. She got lost because nearly all the buildings looked alike – the long, white, wood-framed one story structures characteristic of military structures during that war. At one point she noticed a large group of men in overalls on the other side of a fence and she approached them to ask for directions. They enthusiastically offered assistance, although in such heavy accents that she had trouble understanding them. About this time an officer approached her in a jeep and asked her if she needed assistance. The first lieutenant in the jeep was my Dad and he took her to her destination. He also explained to her that the group of men with whom she was fraternizing was a detachment of German prisoners-of-war. My mother was unaware that Stuttgart was not only an army air base but also a large POW facility. She was immediately struck by my Dad's easy, soft-spoken ways, his intelligence and his sense of humor. They were an attractive couple.

Not long after they began dating, an assembly was called for all hospital personnel where the commanding officer, Colonel Ryan, notified everyone that large crates of oranges were disappearing from the hospital at a prodigious rate. Dad informed on my mother, explaining that his girlfriend was manually squeezing the oranges into pulpy juice and serving the patients. She was a big believer in the efficacy of vitamins and none of the recovering patients on her ward lacked for Vitamin C. When Dad told me this story I was not surprised.

Throughout the childhood of me and my siblings, Mom had a propensity for filling our glasses to the brim with orange juice. For as long as I can remember, she force fed us this juice and justified the routine by citing health benefits. Interestingly she was doing the same thing in 1944 for those seriously wounded soldiers of the Pacific Theatre.

Photographs I have of my parents during their courtship at Stuttgart reveal of couple smitten by love. They met in March of 1944 and were married the following November at the Riceland Hotel in Stuttgart, in a private ceremony whose simplicity was in keeping with wartime restraint. When in February of 1945 Mom learned that she was pregnant, she applied for separation from the army. It took a month for her papers to be processed and in March she left for Detroit to live with her parents, to prepare for my birth, and to await my father's separation from the military. While my parents wrote love letters to each other and spoke of a bright future devoid of kaki and regimentation, world events were moving with inexorable momentum toward the conflict's finale. By the time Mom reached Detroit, American soldiers had just crossed the Rhine and were racing into the heart of Germany while Soviet troops were smashing into Germany from the East. Within weeks Franklin Roosevelt would be dead and two weeks later, at the end of May, Mussolini and Hitler would be history.

Soon after Mom left for Detroit, Dad was transferred to Exler Field outside of Alexandria, Louisiana, his final duty station. He was still in medical administration under the command of Major Ghatti, an army officer and a physician. Dad lived on base in a canvass-roofed hooch for about a month until Mom arrived by train from Detroit after which time they rented a room in a private home in nearby Alexandria and took their meals together in town. By the time she returned to Detroit a few months later, war news was bright and Dad could sense that he would soon be out of uniform. The war in Europe was already over and the conflict in the Pacific was nearing its conclusion. Dad knew that because he had been in service since July of 1941 – five months before Pearl Harbor, he would benefit from an expeditious demobilization.

I was born at Grace Hospital in Detroit on 14 November 1945, three months after the end of World War II. Dad was visiting Mom in Detroit at the time of the birth and, while on leave, helped my maternal grandparents move into their new and imposing home on Oakman Blvd. Their previous dwelling on Monica, two blocks away, had been my grand-parents' residence since 1926. The new home was a large structure, a mix of Tudor and Gothic in architectural style, with a large garage that Gampa converted into an office for his Michigan Drilling Company. At the time of my birth, Dad had only one more month left in the army.

Dad left the army as a captain in early January of 1946. As he was in a hurry to complete law school, he reapplied to Vanderbilt only to discover that in the dislocation of war the law school was temporarily closed. He decided to finish his last year at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville and rented a room for us in a spacious private home that before the war was a Catholic retreat house. There were only two rooms available for rent and the other one went to a first year law student who lived with his new bride. Like Dad, he was a veteran taking advantage of a very generous GI Bill to pay for tuition, books and living assistance. I was only two months old at the time of our move to Tennessee and, of course, have no recollection of the eight months we lived in Knoxville. Mom's prodigious affection for photography, however, gives me a visual record of that time and, as always the case with the first-born, most of the pictures were of me. While Dad was in class, Mom carried me on walks into the fields behind our house to experience nature. On weekends there were picnics with cows grazing in the background. One photograph on the front porch swing shows me offering a graham cracker to my mother. To this day I still am in the habit of dunking graham crackers into milk. We lived in this bucolic setting of Knoxville until Dad got law degree. In a graduation photograph with Dad in cap and gown holding me and with Mom's hand on her husband's arm, my parents looked happy and contented.

It was obviously a time of optimism with the war over, couples getting married, a baby boom beginning, and feverish spending after four years of national thrift and rationing. A photograph of the University of Tennessee's incoming class of 1946 reveals something of this optimism in the expressions of male students registering for courses in coats and ties. Their dress and demeanor reflects a class of men who were older, more conservative and more serious than the typical incoming class of college students. They were, like my Dad, veterans returning to school on the GI Bill. This was the so-called Greatest Generation, young men who didn't complain about tough course loads and intimidating professors because life was now gravy for them. Just months earlier they were sleeping in fox holes, experiencing combat, and distant from families they loved.

With a law degree under his belt in September of 1946, Dad moved Mom and me to Nashville where he planned to study for the bar exam and look for a house. As was typical across the country, housing was in short supply after the war and we were forced to live with Grandmother Andrews and Aunt Sara for several months. Dad could not practice law until after he took the bar exam so he worked in management for Southern Bell at the company's Nashville office. Mom was pregnant with a second child, Dad was studying and working, and tensions began to grow between Mom and her in-laws.

Aunt Sara and Grandmother to an extent exhibited the stereotypical Southern WASP prejudice against Catholics. To make matters worse, Mom was a strong-willed Northerner who seldom let slights or barbs go unanswered. Aunt Sara and Grandmother let Mom know that they disapproved of her being pregnant again when Dad had not yet obtained a position in a Nashville law firm. They not only communicated their dissatisfactions to Dad, but in the subsequent decades they would also tell me and my siblings repeatedly that it was my mother who stifled Dad's ambitions and saddled him with too many children. The friction never ended. My earliest memories of Aunt Sara coalesced around the toy drawer she opened for me and her animated denunciations of my mother. Into adulthood I got along well with my aunt and grandmother because I generally didn't come to Mom's defense and simply remained silent during their denuncations. My more undiplomatic sisters, however, were much more willing to defend Mom and, in consequence, always remained emotionally at arms length from Aunt Sara and Grandmother.

January 1947 was a good month in the history of my family. My little brother John was born on the same day that Dad received word of his passing the bar exam. This was also the month that we moved into a home of our own on Stokes Lane. The house, in the Belmont area of South Nashville, was a convenient five minute walk to Christ the King Catholic Church where Mom attended daily mass with her children and about six blocks from Grandmother and Aunt Sara. During the three years we lived in our little yellow-stone home on Stokes Lane, two additional children were born to my parents. By the end of the decade, I was one of four children. My sister Joan was born in 1948 and my sister Susan was born the next year.

Because we were so close in age – only fourteen months apart – we were never lonely. Mom remained home to dote on us and Dad continued to work in management at Southern Bell. He never practiced law. To this day Mom claims that it was because Dad did not like the contentious nature of law practice and even Dad admits that his distaste for law stemmed much from its proclivity to win cases rather than to seek truth. To this day, I don't believe Dad regrets his decision to eschew law as a career.

Our little home on Stokes Lane was a protective wonderland for me and my three siblings. We enjoyed a tree-shaded fenced-in back yard that we called "Never-Never Land." It was a perfect life for children growing up and we were never in want for attention and adulation from our parents. There was stress whenever we visited Grandmother and Aunt Sara but it was not because we were sucked into the verbal crucible of denunciations against our mother. We were too young at that time. However, as the oldest of four children, I can remember by 1949 that Dad would often have to endure the diatribes against Mom – her Catholicism, her affection for having many children, and her hard-headed unwillingness to take advice. By the end of 1949 I can remember that after our weekly visits to Grandmother and Aunt Sara, loud and animated arguments would ensue at home. Mom refused to accompany us on these visits and Dad was torn between loyalty to his family and loyalty to his wife. We felt loved but we could also sense the tensions aroused by the animosities of our mother and her in-laws.

Chapter Five Uncle Sam and Viet Nam: First Draft

The summer of 1967 was one of the most fruitful when it came to arrowhead hunting. It was also the season of much reading. As was the custom inaugurated back in high school, I would take an hour or two looking for arrowheads and then, to cool off, head for the spring, kneel on the bedrock at the deepest end of the pool, and, as doctor fish and crawdads scurried for safety, dipped my upper torso into the cold water. Then I would grab a book and knock off a chapter or two before returning to the field. By this summer I began to use a golf iron to break up clumps of dirt while looking for arrowheads. Where I acquired this iron I cannot recall as no one in my family played golf.

No longer thinking about college, I was reading for fun and I went through the books with an earnestness which came from sheer pleasure. The entire family was on the farm that summer with the exception of John who was at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, finishing up his training in ground control radar. There was a great void that summer without John and the entire family seemed diminished in its collective vigor from a pervasive anxiety. Vietnam was on everyone's mind if not on their lips.

I also thought of our family vacation the previous summer. Dad had gone west on an ambitious camping trip with the four older children in our white '65 Impala. The heavy canvas umbrella tent and sleeping bags were strapped to the roof and cooking gear was in the trunk. We saw the Garden of the Gods near Colorado Springs, visited the Custer Battlefield in Montana, and hiked around Mt. Rushmore and Devil's Tower. Camping out each night in state or national parks, we followed a rudimentary agenda set by Dad to entertain and educate us. The majestic Rockies, in particular, stood in stark contrast to the older and more familiar Appalachians.

When Dad took us to Rocky Mountain National Park, John and I got the notion to scale Long's Peak, at 14,000 feet one of the highest in that cordillera. We began early in the morning, leaving Dad and the girls to watch the wedding of Lucy Baines Johnson, the president's older daughter, on the miniature B&W battery powered TV which Dad brought for his never-to-be-missed Huntley-Brinkley newscasts. John and I reached the mountain's boulder field by mid-afternoon and, although winded easily from the thin air, enjoyed a snowball fight at a slightly higher elevation. By dusk we stopped directly under the last leg of the climb realizing that without pitons and ropes, scaling the summit would be hazardous in the dark. We rested until darkness descended and viewed the distant lights of Denver. It was peaceful and serene up there, reminding me of the poem by World War II pilot _____ Campbell airing frequently on television like a soap commercial. " …I can "reach out and touch the face of God." This would prove to be the last summer in many years before John and I would share such a sublime moment.

So now a year later I was looking for arrowheads and finding them by the score each day. One of the books I devoured that summer was "The Arrogance of Power" by Arkansas Senator J. William Fullbright who had acquired the reputation of a hardhitting war critic in his role as chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. I also read William Lederer's "A Nation of Sheep," Dostoesvski's "The Idiot," William Manchester's "Death of a President," and Thomas Hardy's "Return of the Native." I also finished William Shire's "Rise and Fall of the Third Reich," a book which I began early in my sophomore year at St. Louis [see friend Kurt von Schuschnigg] but which I had abandoned due to required assignments and Joan's request for it. She had the bulky volume read within weeks.

Although only a year away from graduating with a major in political science, my interest was increasingly moving toward history. I could see this change most dramatically a year earlier in my SLU political science classes with Drs. Legeay-Feueur and Daugherty. Now in the arrowhead field, I could remember the historical anecdotes they employed to illustrate the theories that had been long since forgotten.

We heard that John, as he was finishing up his training in New Jersey, would be reassigned soon and it was anyone's guess where. I spoke to Joan and Susan about a quick trip to see John, got the OK from Mom and Dad, loaded up the VW bug, and took off with Joan and Susan on another fine adventure, my last before leaving for the army myself.

Fort Monmouth provided family visitors with special quarters at a very reasonable rate so we did not have to break out the tent and camping gear. John was free after 4:00 each weekday and we had an entire weekend together. Once John invited me into his workstation and introduced me to some of his classmates. Without thinking, in a sector of the high tech satellite and communications center, I took a flash photo of John standing in front of some highly classified equipment. It didn't dawn on me until later that it was the Ft. Monmouth soldiers who came under investigation by Senator Joe McCarthy for treasonable espionage thirteen years earlier.

We spent the weekend with John at Asbury Park and its beaches. Susan had a little romantic fling with a young man by the name of Jeff Goldstein whose mother was proprietor of a shop on the boardwalk and Joan served as an invited chaperone. John and I flirted with two girls who looked great in their bathing suits but who were too young to take seriously. Interestingly, the girls spoke about how they supported the right of women to have an abortion. I had never considered the subject before and I frankly cannot recall the conversational tangent that conveyed us to this topic. I remember them telling us that they were Reformed Jews.

If it was an idyllic weekend at the beach, what I saw at the military installation gave me some reason for trepidation. For one thing, John hated his military service and was extremely homesick for family and St. Louis University friends. He had the sense that he was wasting time, not learning much, and constantly subject to the whims and machinations of superiors whose only claim to authority was an extra stripe or a little more time in service. It was an inauspicious introduction to the life that awaited me.

Looking back on it, I must confess that we were all aware of college deferments and we knew that all it would take was a letter from Father McGannon, Dean of Students, to verify our status as students in good standing at an accredited university. But we never went that route. Perhaps we should have but I speak from present prejudices and predilections. In fact, John and I had talked of this before. We felt that many people were flocking into colleges and universities all over the country for the wrong reasons. College had become a haven for many young men who, except for the fear of Nam, would otherwise have been content elsewhere. And conversely, many young men were fodder for the cannons with SAT scores too low for college admissions or, if sufficiently endowed with intelligence, with insufficient financial resources to afford a higher education. Of course, this was before the days of inexpensive and accessible community colleges or readily available tuition assistance. The irony was the Higher Education Act, a Johnson priority for his Great Society agenda, was being trumped by the president's increasing obsession with the war. As Johnson later said "The Great Society was the woman I really loved and the war was the bitch who…" - well you know the rest.

In any case, we felt the draft was inherently unfair, favoring the rich and the well connected and victimizing the poor and academically unprepared. ..

There were other reasons for our unwillingness to seek deferment status. Admittedly John and I were both getting a little bored with school and we also knew that Mom and Dad were making some very real sacrifices for an education which we ourselves could not appreciate at the time. Perhaps we were ready for some travel and adventure which, in our naiveté, did not include combat zones. And there was another reason. Mom and Dad had both been officers in the Second World War and had served their country selflessly. I cannot speak for John but, as for myself, I did seek parental approval and thought that to make a dramatic appeal before the draft board in Nashville would look cowardly. Such are the concerns of uncynical youth and I suspect there were many others who enlisted in those years for reasons of parental or peer approval.

I entered the army on 21 September 1967 with little fanfare, waving goodbye to my family as my olive drab bus left the Nashville induction center for Fort Campbell near Clarksville, about an hour's drive north. I recall that there was little talking on the drive up. Few people knew each other and most, I suspect, were like me spending the time reflecting on an uncertain future. Most of the men were young draftees.

Basic training was not the culture I had anticipated. Living for two years in a men's dorm at college was an experience that imparted some important social and survival skills. There was a decided pecking order which was obviously based on physical prowess but there was also – and this came as a surprise to me – respect shown for intelligence and common sense. The shock for me was the extent to which boys in my company were physically unfit. Many had difficulty on the obstacle course. Many feared heights. Many were easily exhausted by the rigors of forced marches and bivouac. The fact that John and I during high school and college routinely ran ten to twenty miles cross country – and this was before jogging became a popular fashion – made the marches easy. On the mile race under full backpack, helmet, boots and M-14 rifle, I was always one of the first to reach the finish. I actually enjoyed the obstacle course and felt that my years playing tennis helped with balance and coordination. When we crawled through the mud at night, negotiating our way under concertina wire and machine gun tracers over head, it was no big deal. In fact, it was sort of fun.

On our first day at the rifle range, we were ordered to fire live rounds at a target just thirty meters away to scope in our M-14 rifles. I was told to fire three shots at the target and retrieve it. When the drill sergeant looked at mine he stopped and told me to put up another paper. I was told to fire three more shots. I did. After the third sequence, the DI took my paper targets and walked over to the other instructors. Whatever he told them, they all looked over at me. In each of my targets, the pattern of three shots all could fit within the size of a dime...

My most anticipated visit came from John as my eight weeks of training were drawing to a close. He was a PFC stationed at Fort Carson, Colorado, and he told me about his adventures and adversities. He was taking classes part-time at the university there and he told me about how he ran into Olympic skater Peggy Flemming at the school library. In retrospect, I believe that John suffered much more than I did from the harassments and humiliations from the army's pecking order, and the arbitrary edicts of petty, small-minded men with a power they could never expect to exert in the fluid and freewheeling civilian world. When John and I shook hands as he was about to leave, I could not control it, hard as I tried, but my eyes watered up and I had to turn quickly away before I embarrassed myself more. I remember thinking what a good brother John was. He was the most sensitive of my siblings, the one who broke down and cried when Milton Evans, our black sharecropper, died. Years later when Ganger died, it was John who broke down and sobbed. The irony was that Ganger always showed more favoritism toward me, showered me with more gifts, and requested that I be the one to stay with her in Mobile. Of all my siblings, it seemed at the time that John had the greatest capacity for sentiment and yet, like Mom and my sisters, was also somewhat disinclined to compromise. These traits would make the regimentation of military life very difficult for him.

From: William Andrews

Sent: Monday, December 26, 2016 6:53 PM

To: Andrews, John (DC); David; dandrews

Subject: Mom and Dad

Hi John and David. I was playing tennis this afternoon in Lewisburg and one of the players was Les Woodard. When he said that his sister is a nurse at the nursing home near the Recreation center, I told him that my mother worked there for a time. His mouth dropped. He asked "Betty Andrews?" When I said yes, he said he remembered her and that Mom would have Daddy come over to play the piano at the nursing home. I never knew Daddy did this. He said he loved Mom and Dad. When I told him that Mom was 98 and living with our sister, he said "amazing." And then he said that our Dad lived to a ripe old age. I told him he was a few months shy of 89 and that he would be 100 now if he were still living. Did you know that Daddy played at the nursing home at Mom's request? John, when you see Mom again, ask her about it. I'm surprised that I didn't know this bit of info. WillyX

Comments by Betty's grandson John Patrick Andrews to his Dad, April 2017: But I do want to be like you. I want to be so strong that I can do everything I have to - sleep, food, comfort, who needs it? I want to be able to put others first consistently, instinctually. I want to be able to recognize the beautiful Spirit of God - in people like grandmama, mom - and I want to be able to keep them in my life. I want to be honest, especially when it's hard.

Mom sold the family's Tyne Blvd home in Nashville in 1972, bought 207 acre farm from Joe Dickinson and she and her family moved back to their farm in Lewisburg.

Monday July 17 - 1972

Beloved John -

Your check for $1,487.00 just came in the mail & I am depositing it immediately. Thank you. I am very grateful that you would clear out the bank there & will also send each pay check through Aug. 15th.

Tyne Closing is August 12 and our meeting with Joe Dickinson will be August 17th (my birthday) after your Aug 15 check arrives. Please, dear John, send every penny you can scrape up. I know you are.

John dear, Daddy thinks you should try your first years to make your money off of the land __________ since you made this huge investment in your farm. He thinks if you work at some regular job like (well, even sales at Friden). You can put each pay-check in beef cattle . That is a big investment & will double every year if you start out buying only springing heifers.

Daddy said since you bought the farm, it's right to make your money that way. He said you can rent your tobacco base each year & make $1500.00 that way too. Beef is big money.

Daddy said construction would take a huge investment, and he said the farm was big enough for you to invest in. He thinks you can really make a real thing of beef cattle if you put even a selling or teaching or modest monthly salary in it. If you set aside your salary each month.

You cannot believe how beautiful our farm is becoming with Daddy working with the side-winder every day. We will have wonderful grazing land.

GOD BLESS YOU. Bill loves Mexico. Daddy, Joan, Susan, Dave, Miriam.

Joel and Mariah (horses) are perky and happy.

Chuck H. Spell:

John, on a whim, I read about your father... what I read was Very Touching. I'd have to say, your father had to be a Great Southern Man, as Great Southern Men go. Seems he was a very positive role model, and a Very Good Man. And Yes, John, I do firmly believe your father is in Heaven.

Sounds like you grew up on a Family Farm, as did I. I've done everything you can do on a Family Farm except String Tobacco and Pick Cotton. But my Mom string tobacco as a girl and my father picked cotton – so I think I am still covered in that respect.

On your father's side you have a connection to a former Commissioner of the IRS. NOW THAT IS VERY INTERESTING!!!! considering where I ended up working right after I finished at the College of Charleston in 1986.

Prentiss Andrews :

I wanted to say that my wife and I were very moved by your brother's fine memorial to your father. We have lost our beloved parents and had to try to hold back our tears when reading his piece.

Prentiss Andrews

Denton, Texas

Daughter-in-law Sue was staying with Mom at a time during about 2012 or so and Mom asked her to open the curtains to let a little light in. Sue told her that the curtains were open. Mom responded by saying, I really am blind then!

Daughter Susan recalls being in the back year at her grandparents', Gampa and Ganger's, house in Detroit when her brother Bill came out and said, "Our Daddy is here." Susan replied, "Of course he's here." Bill said, "No our real Daddy." Susan said, "Gampa is our real daddy." Right after this a tall, skinny man came out and hugged her and Susan was stiff and didn't know what to think. This is the first she remembers of her father.

Susan also remembers the first day at the farm as her sister Joan spent hours chasing all of the chickens all over the yard and then putting them all into the car because she wanted to bring them back to Detroit with her. Her parents asked her why she had done this and told her that the family was not going back to Canada or Detroit. One of Susan's first memories of the farm that first week or month was a windy stormy night when the corn had to be harvested and put into the barn before the rain. The corn was in the field beyond the corn field and arrowhead field near the high field in the field with the sink hole in it. The corn was huge. The boys from the Eavan family, the black tenant family who lived on the farm, Harvey and Howard, were out there, but not Milton. The tractor lights were on against the wind and the oncoming rain and it was beautiiful, but Susan was afraid she would get lost in the rows of corn if she let go of her mother's apron. She also remembers a chicken named knotthead that would always run into fences. Susan thinks he was mentally ill and that he was the one who fell into the pond and got frozen. Joan carried him around in her pocket for two days and he recovered but was never the same again. She remembers Suzie her cow who fell into the sink hole to the side of the house and Daddy pulling her out with the tractor. She never seemed to grow more after that. Susan's memories of Lake House in Canada were the water and the wind blowing against the water at night. She remembers the well in the shape of a hand pump. Her mother had a garden that a farmer tilled for her and Susan was out there with her mother eating a sandwich. Susan was playing in dirt and found a grub and called to her mother, "look." Her mother said "eat it" every time Susan said, "look Mama." Just as Susan was about to put the grub into her mouth, her mother screamed and Susan dropped it. She remembers really feeling bad when Bill and John burned Gampa's bus. She remembers them getting into trouble and hiding, and she remembers crying and hearing the fire engins and hearing Bill and John cry or get scolded by Uncle Ted. She also remembers Uncle Ted taking her out on his motor boat on a place in Detroit like Old Hickery Lake in Nashville. Only Susan, Jamie and Uncle Ted were there. Susan thinks she fell into the water and couldn't breath and she remembers being afraid of water after that. Susan remembers floating on the water head down at Lake House in Canada and being able to hear things such as the sound of the water but being unable to do anything. She remembers she and Joan getting lost in Detroit and a policeman bringing them home. The man sat on a store counter and gave them an ice cream cone. Joan kept saying, "2850 Oakman Blvd," over and over, but he couldn't understand her since she spoke so fast. The policeman put her on the counter at the restaurant and then Susan told Joan that she could find the way to the school where their mother had gone to take Bill and John to school (St. Bridget's). In Canada Susan and Joan got lost and mounted police brought them back.

When Susan and Joan were 4 and 5 and their mother had taken a ship to Europe with their grandmother, their Aunt Sara told them that their mother was dead; that she had drowned. Up until 4 or 5 years ago (1998?)Joan and Susan had never talked about this. One time Susan had talked to her father about putting the farm in her mother's name also because if he died Aunt Sara would get the whole thing. So after Susan built the Chalet on the farm, she told Daddy that not also putting the farm in Mama's name wasn't a fair thing to do to her mother. This was after her father had collapsed at Mass while playing the organ. So her father said that the farm had nothing to do with her mother. That his father had given it to him and his sister and it had nothing to do with Mama. Susan told Daddy that when they moved to the farm, it looked like a trash farm because it had all those barns around the house and the upstairs had corsets and snake skins and it was real messy. There were chicken coops, the smoke house, the kitchen of the original house that had burned down that was used as a garage and old barns. She told Daddy that every night and all day long while Daddy was at school, Mama would pull up all those bushes that had stalks like trees and red berries. She would pull them up by their roots. And every night when everyone got home from school, they would have a bonfire. And now it looks like a park and that Mama made it look like that. "How can you say it has nothing to do with Mama?" Aunt Sara has never lived there one day in her life. To prove her point, Susan said she had never told anyone this before, but Aunt Sara really hated Mama. (Susan felt that her grandmother had talked Aunt Sara into hating Mama). Susan's father said that wasn't true. To prove it, she told him that when she was 4 years old and Joan 5, when Daddy brought them to Aunt Sara's house, and Daddy left Bill and John there for a week and then Susan and Joan there for another week, one night when Joan and Susan were playing on the floor and grandmother was sitting on one recliner and Aunt Sara on another, Aunt Sara called them over to her chair and showed them a picture of an oceanliner in the newspaper. She said, "look your mother's ship sank and your mother's dead." Joan grabbed Susan's hand and pulled her into the bedroom as Susan was crying and told Susan that Aunt Sara was lying, that she hates Mama and Mama wasn't dead. So, years later, Daddy told Susan what Susan had said about Aunt Sara was a lie, that it never happened. Susan was so shocked that Daddy called her a lier than Susan said, "Daddy why do you choose to believe Aunt Sara instead of us? You've never stuck up for Mama and act as if Mama is wrong. If you don't believe me, ask Joan. She was older at five and she'll tell you." Joan and Susan had never talked about it. It was raining the night Aunt Sara said this and Susan remembers everything about it. Joan said, "Come on, we'll run away." They took some toys they had been playing with and an unbrella. A couple days later after telling Daddy this many years after it happened, Susan picked Joan up at airport and said, "Joan do you remember? Daddy says I am lying." Joan replied, "Of course I remember." Then Joan told Susan things about that weekend that she didn't even remember. Susan asked how did you know that Aunt Sara was lying. Joan said, "I didn't, but I knew how much Aunt Sara hated Mama and just hoped she was lying." Joan said that Daddy never asked her about this as Susan had asked him to do.