Information from Betty Jane Andrews:

Sheridan Knowles was a famous playright in England who graduated from Aberdine University in Scotland. He was poet-lauriet of England and knighted by King George III. His wife was the pinkie (posed for Pinkie, the companion picture to Blue Boy) in Blue Boy by Thomas Gainsborough. It is safe to say, athough no proof exist, that Sheridan Knowles (or his parents or earlier ancestors) had to renounce his Catholic faith to have obtained the education he did and to have received the honors he received from England.

12/18/04 Phone Interview with Elizabeth Jane Early Andrews: "I do recall that Sheridan Knowles, Frances Knowles' uncle, came to America after his conversion to the faith (he did not convert, but his son Richard Brinsley Knowles did). All of his early writings before his conversion were very anti-papist."

Annie Brindle met a woman from Williamsburg, Virginia who said that the one who posed for the Pinkie painting was the aunt of Jane Austin (that Lady Sheridan Knowles, the one in the Pinky painting, was the Aunt of Jane Austin). Lady Sheridan Knowles' father owned a crystal factory in Ireland and she married Lord Sheridan Knowles who was from England and he was the one actually related to Jane Austin. [They may be confusing Lady Sheridan Knowles with Elizabeth Ann Lindley Sheridan.]

____________

EXCERPTS FROM THE LIFE OF JAMES SHERIDAN KNOWLES by his son Richard Brinsley Knowles

Hazlitt about James Sheridan Knowles:

The seeds of dramatic genius are contained and fostered in the warmth of the blood that flows in his veins; his heart dictates to his head. The most unconscious, the most unpretending, and the most artless of mortals, he instinctively obeys the impulses of natural feeling, and produces a perfect work of art. He has hardly read a poem or a play, or seen anything of the world, but he hears the anxious beatings of his own heart, and makes others feel them by the force of sympathy. Ignorant alike of rules, regardless of models, he follows the steps of truth and simplicity; and strength, proportion, and delicacy are the infallible results. By thinking of nothing but his subject, he rivets the attention of the audience to it. All his dialogue tends to action; all his situations form classic groups. There is no doubt that 'Virginius' is the best acting tragedy that has been produced on the modern stage. … There is no impertinent display, no flaunting poetry; the writer immediately conceives how a thought would tell if he had to speak it himself. Mr. Knowles is the first tragic writer of the age; in other respects he is a common man, and divides his time and affections between his plots and his fishing tackle; between the Muses' spring and those mountain streams.

Leigh Hunt once said to me, "No one could see your father in a room or on the stage without at once saying, 'That is a remarkable man.'"

...that sparkle like his own eye; that gush out like his own voice at the sight of an old friend. We have known him almost from a child, and we must say he appears to us the same boy-poet that he ever was. He has been cradled in song, and rocked in it as in a dream, forgetful of himself and of the world."

The italics in this extract are mine. I have made them because they recall my father to me, in some of his words, so perfectly. And if it were my duty to state what, in my opinion, was the main source of his success as a dramatist, I do not think I could do better than repeat the words - "He bears the anxious beatings of his own heart, and makes others feel them by the force of sympathy."

From the "Glasgow Herald," shortly after my father's death, in a letter written by "an Old Pupil”:

"James Sheridan Knowles! How my heart warms at the name of that single-minded and enthusiastic son of genius! For more than two years I was a member of his elocution class in Glasgow; and I look backward to the days which I spent under his tuition as amongst the brightest and most genial of my life. To become a pupil of Knowles' was to become in a great measure his adopted child. He loved his 'boys' with an affection greatly analogous to that of a father, nor was his kindness ever thrown away. We never looked upon him in the light of a task-exacting pedagogue. There was not one of us who would not have gone through fire and water for 'Old Knowles' or 'Paddy Knowles,' as in loving familiarity we called him, almost to his face. The sternest chastisement which he could inflict upon offenders was to debar them from the school-room for a given number of days. In other seminaries holidays are the reward of merit and diligence; with us they were regarded as penalties.

"Though in the receipt of a considerable income from class fees, Knowles in process of time slipped into the quagmire of poverty. This untoward state of things was not attributable either to extravagance or dissipation. In the words or a fellow-countryman and kindred spirit -

'Even his failings lean'd to virtue's side.'

Never could he hear unmoved the tale of sorrow or the supplication of penury. His last shilling was ever at the service of the man who could make out a plausible case of hardship or of want. Unfortunately, the designing and fraudulent took advantage too often of the generally-known temperament of the poet, and shoals of sordid leeches were ever ready to fasten upon him whenever he had a guinea in his purse. Much of the money thus disbursed was nominally in the shape of loans; but, as the lender seldom exacted acknowledgments of debt, the coin might as well in most cases have been buried in the recesses of the 'Dominie's Hole.'"

His habit was to write as much as possible in the open air and he would leave home after an early breakfast and stroll along the Newhaven sands with his book and pencil, returning to a four o'clock dinner, after which he would read to my mother what he had written, and then walk up to Edinburgh to attend his classes there. I well remember those evenings: - my mother sitting in her invalid chair, feeble after a long illness, my father reading to her what he had written during the day, dwelling hopefully on the progress of his work, and expressing his confidence of success. Of a morning he would sometimes take his younger sons down with him to the beach, and help them to sail a large yacht-rigged boat, and in sailing which, I believe, he took as much pleasure as they did. Indeed be was always ready to put his hand to any work of this kind to amuse us, and I remember his turning boat-builder himself on one occasion for my benefit, and making and rigging for me a lugger of which I was becomingly proud. Many a game at marbles did he play with us; many a kite was the work of his hands. He took especial delight in encouraging and directing our juvenile attempts at gymnastics, and whilst we lived at Edwin Place, near Glasgow, he put one of his sons on skates when he was seven years old, and trained him himself. He held that a boy’s amusements are as important a part of his education as his lessons.

The "Spectator" prefaces its criticism of the actor by giving a portrait of the man: -

"If we wished to see the model of a manly, open-hearted, generous fellow, Mr. Knowles is his image; somewhat coarse, perhaps,-a little provincial too; but there he stands- a broadside of integrity and manliness -a pyramid of strength and burliness; yet by the eye and the softening of the manner one in whom may be detected a gentle and affectionate spirit, a tender and inflammable heart.... His evident want of familiarity with the stage, his occasional failures in attempts at mouthing, and sometimes his straight-forward business-like procedure, more than once gave us great delight; we said, here is a natural man on the stage, going through his part as if he were on the great stage of the world. But for the true part of a hunchback, be he benevolent or malignant, he has too many burly perfections; and in working it out he wants concentratedness, calmness, and the consciousness of power. What he did in this way - for now and then he assumed the imposing - had too much the formal air of an elocutionist showing how the thing should be done."

There was something fearless, modest, generous, and real, about Mr. Knowles' deportment that won us completely; and the whole occurrence put the man and the house upon a familiar and sincere footing, that we like, but have never seen before. It was not one of his majesty's servants cringing to a tyrant public, but an artist facing his friends and fellow men. It was Ben Johnson in the nineteenth century."

One more scene yet I must record in that night's performances. It took place before no audience, and amid no waving of hats and handkerchiefs. "'How did you feel at the moment when your victory had reached its culminating point?' 'I cannot tell you what I felt,' was the reply. 'But I shall tell you what I did. As soon as they let me away from the front, I ran trembling and panting to my dressing-room, and bolting the door, I sank down on my knees, and from the bottom of my soul thanked God for his wondrous kindness to me. I was thinking on the bairns at home, my boy; and if ever I uttered the prayer of a grateful heart, it was in that little chamber.'"

I believe it was the bitterest regret of his last years, that he had spent so much of life 'without God, and without hope in the world.' It was a constant source of abasement, that while familiar with all the knowledge of which men boast, he had yet remained in darkness about God, and without receiving into his heart the love of God in Christ his Saviour.

On death of his son, Dr. James Knowles:

Amongst my father's many Glasgow friends was Captain Thomas Blair, of the Hon. East India Company's navy. One night after they had supped together prior to Captain Blair's starting the next day on a voyage to Calcutta, as they were bidding each other good-bye, Blair placed in my father's hands a roll of bank-notes, with these words: "If we never meet again, Knowles, regard this as a legacy." It was £500. Some time before this, seeing my father struggling with a large family, and being himself a bachelor and very wealthy, he offered to adopt one of his sons, and provide for him. But you might as well ask my father to give you his heart out of his breast as to part, even to such a friend and on such terms, with one of his children. So that offer went off. "Well, then," said Blair, "bring up your eldest son to the medical profession, and as soon as he is qualified, I will get him an appointment in my own ship."

That sealed my brother's fate for the medical profession. As soon as he had passed his examinations, my father received from another friend the offer of an appointment for him, as head surgeon on board one of the king's ships. He at first accepted it; but, on second thoughts, doubted the propriety of placing so young a man in so responsible a position, and declined it. Shortly aftenwards my brother was appointed assistant surgeon to the "William Fairlie," H.E.I.C.S.; and in his first voyage in 1832, reached Calcutta, and died of fever.

I shall never forget the occasion when the news reached us. We had been anxiously expecting a letter, and one day my father took me with him to the city to make enquiries. His first visit was to an office where he was known. There was no letter; and it was clear there never would be one as soon as the gentleman who saw him said, "I don't know whether you are aware that there has been a good deal of sickness on board." That was enough. My father just managed to say, "Has anything happened to my son?" The answer, "I don't know," did not deceive him. As soon as he got into the street he burst into tears. ''Your brother is dead," he said to me; and with his heart bursting, he went weeping along the streets till we reached another office, where, not knowing who he was, a clerk showed him the last list of the ship's company, with the entry, "James Knowles-dead."

Not a word or a look of all this has passed from my memory, for his death was the first death, except of infant children, which had happened in our family, and we were all very fond and proud of him. And no wonder, for he was a lion-hearted young fellow, and a fine specimen of manly strength and beauty. The thought of fear never entered his mind, nor of self if any one needed help. Walking with him on the pier at Newhaven, one day when the tide was in, he suddenly threw down his hat and stick and dived. I looked down and saw a dark body struggling in the water near the bottom. In a few seconds my brother brought it to the surface. It was an idiot lad, who had fallen off the ledge of the pier, and would certainly have been drowned but for this interposition. On another occasion, at the same place, he saved the life of a man who was taken with cramp while bathing. He swam out to him and brought him to shore. Again at Newhaven, while rowing with two fellow students, an oar broke, or was lost, and there not being a spare one, the boat, which was sharp at both ends, was unmanageable. In this perplexity they lowered their anchor, while my brother stripped and, though the boat was more than a mile from shore, swam to land, got an oar, and swam back with it.

He was at that time finishing his medical studies at Edinburgh. The students bad been annoyed by a pugilist who amused himself with insulting and then thrashing them if they showed fight. Unluckily one day he fell foul of a student who knew something of sparring, and was not to be trifled with. "If," said my brother, "you were a gentleman I should require from you the satisfaction of a gentleman." [The stupid practice of dueling was not then out of fashion, and there had been more than one duel just then amongst the students.] As you are a pugilist I will take you in your own way. Meet me in the meadows at six this evening." They met, and after a fight which lasted an hour and twenty minutes, the fellow went home with a sound thrashing, and cured, for the time at least, of his ruffianly propensity.

But a pluckier thing still, and which was the talk of all the schools in Glasgow the day after, was his charging, single handed, a company of curlers [Curling is simply the game of bowls played upon the ice, the curling stone being flat-bottomed instead of round, and grasped by a bent handle. It is not an instrument with which a skater would like to come into collision], and rescuing from them a young student who would othewise have fared badly at their hands. We had been skating on Middleton Pond, near Glasgow, but after a while my brother took off his skates, strapped them up, and walked up and down the bank watching the others. It was thawing, and the curlers having worn out the ice at their end of the pond, came to ours and began to play there. This was very unfair and excited much indignation amongst the skaters, one of whom, a spirited young fellow, took his stand upon the line of play they had marked out, and swore with an oath that the game should not go on. One of the curlers said he would soon settle that. He took the curling stone and was about to drive it at the skater, when the latter finding his position untenable, began to stamp with all his might upon the ice in order to destroy its surface, and spoil the game which he saw he could not prevent. This bare statement of the thing gives no idea of the extent to which blood was up on both sides. The rage and excitement were intense, and when the curlers saw they were likely to be baffled they rushed upon him, and he, instead of giving them leg bail upon the ice, as he easily could have done, most injudiciously made a rush for the bank, and ran crippled by his skates till they overtook him in a field close by, knocked him down and began to belabour him.

My brother, who was standing with me a little way off, had taken no part in all this, nor did he approve of the skater's temerity, which he thought rash, nor of his flight, which he thought fatal. But now he took a part in it with a vengeance. Dashing in amongst them he laid about him right and left with his skates with such surprising effect that in less than a minute the curlers were ftying across the field in every direction. It was really a fine thing to see a lad between nineteen and twenty, "like an eagle in a dove-cot," not "fluttering" the fellows of whom there were not less than a dozen, but sending them scampering off like so many hares. No doubt he wielded an effective weapon, but it was risky work for all that, and if the men had stood their ground and rallied he could have had no chance with them. The onslaught however with which he came crashing down upon them was so sudden, unexpected, and fierce, that they were seized with panic. It was sauve qui peut in a moment; but the victor lost his hat in the melee, and had to walk back to Glasgow with his handsome curly head bare.

Neither my father nor mother had any favourites amongst us: but, as their first child, the companion of their early days of poverty, he must necessarily have had some preference in their affections, and it was an awful blow to them to lose him just as they had started him in life with such good prospects, and when they were preparing to welcome him back to a home which had been so brightened by prosperity in the interval of his absence. He was not to see it. After spending some weeks in Calcutta with Captain Blair, he returned to the ship, took jungle fever from an officer whom he attended and cured. The physician could not cure himself. One day, Captain Blair, who had meantime resumed the command, went into his cabin and sat with him. He said he felt that the worst was over and that he should now rapidly recover. Presently he expressed a desire to sleep, and in that sleep he died.

As for the subject of this memoir I can say, looking back to my earliest recollection of him (Sheridan Knowles) and the impressions made upon my mind from my childhood upwards with regard to him, that I have rarely known a man who had a stronger sense of religion, deeper veneration for it, or who carried out its precepts more in the practice of his life. Therefore if we must speak of his "conversion," let us clearly understand what sort of conversion we mean.

It was certainly not that of the flagrant sinner whose life has been a scandal to his neighbours, and whose heart by some touch of grace has been suddenly melted into penitence. Nor was it that of the "respectable" sinner perfectly correct in his exterior, but whose heart might as well have been made of putty for all the loving kindness that ever came out of it. Few men ever went through the rough work of sixty years so free from reproach. That character which comes nearest to that of "Christian" the character of "gentleman" - he had filled so as to win for himself

"Golden opinions from all sorts of people."

No man was more considerate of the feelings of others, which I take to be a main note of both characters; nor more upright in his dealings, more straight forward, more sensitively honourable, more incapable of meanness or injustice. He was not perfect, any more than the rest of us, but of none could it be more truly said that his faults-vices he had none, nor the shadow of a vice-were the excess of his virtues. His acts of generosity were habitual. If he saw merit pining in the shade, it rejoiced him to help it into the light. He was a fast friend and stood by those he loved all the more staunchly if they happened to be in trouble. Of his plays, it is not enough to say that they are free from objection; they never fail to inculcate a high tone of morality, and even, occasionally of religion. I have shown to what practical use, when a very young man, he turned Rowland Hill's preaching; and I can vouch for him that both by example and precept he strenuously aided my mother's pious efforts to give her children a Christian education. Another mark of the Christian and gentleman I see in his chivalrous respect for women and in the purity of his conversation. With him in all sorts of companies, -literary, theatrical, professional; amongst merchants, manufacturers, sea-captains, or what not, I never heard an impure expression from his lips. We have here then, I submit, a very fair Christian to begin with; and if we are bound to speak of the change which took place in him somewhere about his sixtieth year, as a "conversion," we must qualify the term by bearing in mind that it produced in him neither a sudden nor a very great alteration. It was rather a development of what he was already than the substitution of something new, and it by no means justifies the statement in the sermon already quoted that he spent sixty years of his life "without true religion."

One phase of it, indeed, was a total departure from his antecedents. We have seen how large was the heart of his youth and middle age 1 - how warmly he advocated the cause of Catholic emancipation; and how in his days of struggle and poverty he could find time to lecture for the Roman Catholic poor schools of Glasgow. Earnest he was in those days in his own faith; not indifferent to the obligations it imposed upon him as a citizen and the head of a household; yet putting his creed into practice by acts of kindliness to all whom he could befriend without asking whether at their morning and evening devotions they knelt before a crucifix or the back of a bed-room chair. That is not the man we have now to contemplate. Instead of lecturing for Catholic poor schools, he will lecture on the Errors of Popery to raise funds for the Irish Church Missions. He no longer believes that the Papist can be loyal to the throne or inherit salvation, but regards him as a tool in the hands of a designing priesthood, working for the overthrow of the constitution under which he lives, and especially for the damnation of his own soul. I am not putting this too strongly. I state it at all very much against my will. But as a faithful chronicler I am bound to say that after his conversion no one cried, "No Popery!" louder than he did - in his books, on the platform, in the pulpit, or in private conversation.

But here again we find in him a thorough sincerity. Whatever their value as contributions to sacred literature, his two controversial books, and his essay on the Gospel of St. Matthew, evince strong convictions, and were not produced without great industry. Of the former, the first published was the "Rock of Rome; or, the Arch-Heresy." It combats the position that St. Peter was the head of the Apostles, and denies that he was ever at Rome. In the second, "The Idol demolished by its own Priest," -he proposes to refute a work of his late Eminence Cardinal Wiseman on the Holy Eucharist.

Though he lost all patience in speaking of popes and cardinals, there was some thing very affecting in the gentle, endearing way in which, after an animated invective, he would ask you for your soul's health to lay aside your own convictions and adopt his. And, again, if like myself you were a Catholic and happened to dine with him on a Friday he would have the best fish to be got for your dinner...

But his conversion had other fruits than controversy; it did not, as I maintain, produce a change of heart, but it converted a man of strong religious feelings into one who became all-absorbed by them. Religion had never been absent from his thoughts; was never named by him without reverence. I do not believe the sun ever rose or set upon him in all his life that he did not pay the Christian's homage to his Creator; it was only the fulfilment of a strong probability that, with advancing years, he came to think more often and more earnestly of the solemn "hereafter,'" and resolved that thenceforth this thought alone should occupy his mind, to the exclusion, as far as possible, of every other. That he did so with sincerity I have the best reason, apart from the impossibility of his doing anything otherwise, for knowing. When an offer was made to him through myself of £500 for a novel, a sum which would have been very acceptable to him at the time, he wrote to me, "I have put my hand to the plough and will not turn back." Other evidences were not wanting: the resignation, for example, with which he bore the physical sufferings of his latter years, and his detachment from the interests of life. But upon this subject it may be better that I let others speak.

It is confessed by all who have sketched the character of our departed friend that he abounded in strength and simplicity of character. He united in himself more forcefully and more beautifully than is even common with men of genius, strength of intellect and simplicity of heart. There was at times a piercing brilliancy, but more frequently a subdued and subduing tenderness, in his lustrous grey eye. He was gifted with a woman's tenderness, a man's resoluteness, and the playfulness of a child [very true]. These qualities were conspicuous in his religious character, as they should have been; for religion is not repugnant to nature, is not sent to supplant but to direct it. When he began really to live, his natural simplicity became Christian transparency and guilelessness, his manly resoluteness became Christian firmness, and his childlike playfulness became chastened into Christian cheerfulness. It is God's plan to make of men 'little children' to verify Christ'sends. 'Except ye be converted, and become as little children, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of Heaven.' It excites our wonder to see the scheming man of the world, when he comes under the transforming influence of the Gospel, become a 'little child' in simplicity and trust; but it is more beautiful, because more natural and less restrained, to see Christianity build itself upon natural and uncorrupted simplicity of character, if that be not weakness; but if allied with manly strength of intellect and purpose, there is every ennobling element, all the material for spiritual beauty and grandeur of nature.

"Our beloved friend was all this in an eminent degree. His piety in every respect was manly strength and childlike simplicity; he received Christ as his Saviour, and clung to Christ with all the unquestioning trust of a 'little child,' and was delighted with every discovery he made of that Saviour's beauty, as the child with new gifts, or the explorator with new discoveries. And yet he rendered to Christ the firm adherence of one whose loyalty was not a sentiment merely, but a life. To learn Christ and to follow Christ became the one object of a most sacred ambition; his intellect embraced the simplest truths of the Gospel, his imagination was fired by its glories; but, above all, his heart was thrilled with its glad tidings. Hence he became a most diligent student of God's word. It had a chann for him no other book ever had. Having given an intelligent faith to its inspiration and divine authority, he bowed his intellect to whatever he regarded as its teachings. To ascertain its meaning on the least and greatest of its themes, he considered no protracted labour too great.

"His Greek Testament became his constant companion, and he committed to memory the whole of St. John's Gospel, the better to impress its truths upon his mind. I have seen him, when confined to bed, and amidst the paroxysms of acute rheumatism, still eagerly pondering that Testament, and throwing as much earnestness into an hour's talk about what he was reading, as though he had been addressing a large audience-his broad chest expanding, his eagle eye flashing, until compelled to desist by a fresh assault of acutest pain. A friend who saw him often during the first year of his real life, and who knew him well, says he pursued the study of God's word with such an ardour as to threaten injury to his health.. Never have I seen any one so thankful for the least aid in clearing up the meaning of what was doubtful in God's word; but while he would for this purpose sit at the feet of any unlettered Christian, he held what he had embraced as God's truth with the utmost tenacity. He was very much what Wesley regretted he had not been - 'a man of one book' in his Christian studies. What he knew of Divine truth he got from the fountain head of truth-the Bible.

____________

Sheridan KNOWLES, M.D. (1784 - 1862).

Irish dramatist and actor

Life

James Sheridan Knowles; born at Cork on 12 May 1784, was son of James Knowles [q. v.] the lexicographer, by his first wife; to London, 1793; studied medicine there and grad. Aberdeen; army; joined Cherry's touring company; played with Edmund Kean.

Richard Brinsley Sheridan, from whom he derived his second name, was his father's first cousin. At the age of six he was placed in his father's school at Cork, but in 1793 moved with the family to London. There he made early efforts in verse, and at the age of twelve attempted a play, in which he acted with his juvenile companions, as well as the libretto of an opera on the story of the Chevalier de Grillon. A few months later he wrote' The Welch Harper,' a ballad, which was set to music and became popular. He was befriended by the elder Hazlitt, an acquaintance of the family, who helped him with advice and introduced him to Coleridge J and Lamb.

His mother, from whom he received much encouragement, died in 1800; and on his father's second marriage to a Miss Maxwell soon afterwards, Knowles, unable to agree with his stepmother, left the parental roof in a fit of anger, and lived for some time from hand to mouth, helped by his friends. During this period he served as an ensign in the Wiltshire, and afterwards (1805) in the Tower Hamlets militia; studied medicine under Dr. Willan, obtained the degree of M.D. from the university of Aberdeen, and became resident vaccinator to the Jenuerian Society. Meanwhile he was writing small tragedies and 'dabbling in private theatricals. Eventually he abandoned medicine and took to the provincial stage. He made his first appearance probably at Bath. Subsequently he played Hainlet with little success at the Crow Street Theatre, Dublin. In a company at Wexford he met, and on 25 Oct. 1809 married, Miss Maria Charteris of Edinburgh. They acted together in Cherry's company at Waterford, and there Knowles made the acquaintance of Edmund Kean, for whom he wrote 'Leo, or the Gipsy,' 1810, which was performed with favour at the Waterford Theatre. About the same time he published a small volume of poems. After a visit to Swansea, where his eldest son was born, Knowles appeared on the boards at Belfast. There he wrote, on the basis of an earlier work of the same name, a play entitled 'Brian Boroihme, or the Maid of Erin,' 1811, whicli proved very popular.

But these efforts produced a very small income, and Knowles was driven to seek a living by teaching. He opened a school of his own at Belfast, and composed for his pupils a series of extracts for declamation under the title of 'The Elocutionist,' which ran through many editions. In 1813 he was invited to offer himself for the post of first head-master in English subjects in the Belfast Academical Institution; but this appointment he declined in favour of his father, contenting himself with the position of as months; but by the time it was ready Kean had accepted another play on the same theme, which was not performed at Drury Lane until 29 Muy 1820 (genrst, Hi*t. Stage, ix.. 36). Knowles meanwhile produced his drama at Glasgow, where Tait, a friend of Macready, saw it, and brought it under that actor's notice. It was afterwards performed at Covent Garden on 17 May 1820, with Macready in the title-role, Charles Kemble as Icilius, Miss Foote as Virginia, and Mrs. Faucit as Servia; and although Genest denounces it as dull, it ran successfully for fourteen nights (ib. pp. 56-7). Among the congratulations which Knowles received was one in verse from Charles Lamb. Knowles then remodelled his 'Caius Gracchus,' and Macready brought it out at Covent Garden on 18 Nov. 1823. At Macready's suggestion he afterwards wrote a play on 'William Tell,' in which the actor appeared witli equal success two years later. Knowles's reputation was thus established, and Hazlitt in his 'Spirit of the Age,' 1825, spoke of him as the first tragic writer of his time. But Knowles made little money by his dramatic successes. In 1823 and 1824 he added to his income by conducting the literary department of the 'Free Press,' a Glasgow organ of liberal and social reform. His school did not prosper, and he took to lecturing upon oratory and the drama, a field in which he won the praises of Professor Wilson in the 'Noctes Ambrosianne.'

Knowles's first comedy, 'The Beggar's Daughter of Bethnal Green,' was produced at Drury Lane on 28 May 1828. It was based on the well-known ballad, which had already inspired a play by Henry Chettle and John Day (written about 1600, and printed London, 1659). Though expectation ran high, Knowles's play was damned at the first performance; the verdict was perhaps unduly emphasised by the presence of many illwishers from the rival house of Covent Garden, then temporarily closed. Knowles at once set to work to redeem the failure. In 1830 he and his family left Glasgow and settled near Newhaven, by Edinburgh, and at the beginning of 1832, but there was delay in producing it. Knowles demanded his manuscript hack, and took it to Charles Kemble at Covent Garden. It was produced there on 5 April 1832; Julia was played by Miss Kemble, and Master Walter by the author himself, who thus returned to his early calling. The comedy was a great success, and enjoyed an almost uninterrupted run till the end of the season, but Knowles's acting did not meet with much approval. On taking 'The Hunchback' to Glasgow and Edinburgh, he was received with enthusiasm by his former friends and pupils. When his next important play,'The Wife,' was brought out at Covent Garden on 24 April 1833, Charles Lamb wrote both prologue and epilogue; and an article in the' Edinburgh Review ' at this date described Knowles as the most successful dramatist of the day.

On 10 Oct. 1837 appeared 'The Love Chase,' which, with the exception of 'The Hunchback,' has retained more public favour than any of Knowles's plays. With Strickland as Fondlove, and Elton, Webster, Mrs. Glover, and Mrs. Nisbett as Waller, Wildrake, Widow Green, and Constance respectively, the play was a brilliant success, and ran until the end of December.

Knowles, notwithstanding adverse criticism, continued to act up till 1843, and by his own account thus made a fair income. He acted in 'Macbeth' and in some of his own plays at the Coburg Theatre, and also in the provinces and in Ireland. After playing with Macready in 'Virginius' before an enthusiastic Loudon audience, he paid, in 1834, a very successful visit of nine months to the United States. He spoke to the audience and as he spoke he was frequently interrupted by applause, and by vociferous negations whenever he alluded to the necessity of his exile." "The whole discourse," says another reporter, "was received with tremendous enthusiasm, and the cheering at the termination was loud and long continued." Says a third: "The possibility of losing Knowles entirely seemed hardly to have struck the audience until he arrived at the last sentence, and it was met by a most hearty and universal negative. It is not in our power to describe the sort of emotion that seemed to pervade all his hearers; for there was something so very captivating in Knowles's manner, from its mere sincerity, that it was felt by box, pit, gallery, orchestra, and stage-for all were densely crowded."

HE sailed from Liverpool for New York early in August, 1834, on board the Columbus, Captain Cobb. If "troops of friends " be one of the riches of this life no man was ever richer. "On Thursday," says the "Liverpool Albion" of that date, "the eminent dramatist arrived here. On Friday he partook of a farewell dinner at the Mersey Coffee House with a few friends, who afterwards accompanied him on board the Columbus, in which vessel every berth had been taken. Numerous friends lined the piers anxious to pay their parting respect to the dramatic poet, whose spirits were more than usually depressed, although it was gratifying to see colours, flags, and handkerchiefs, waving from the different villas on both sides of the Mersey, in compliment to him in passing down the river. His friends left him at the Rock, and the three cheers at parting were re-echoed from the shore."

Nine happy and, upon the whole, prosperous months he spent in the United States, and he returned to England enthusiastic about the people, and deeply impressed with their destiny as a nation. He was delighted with the straightforward, unaffected simplicity of their manners; and he was one of the few literary men who at that date visited the States and brought back a glowing report of them. As a man, in nowise superficial himself, but who, thoroughly in earnest in all his acts and opinions, respected the reality of things, and looked with contempt upon appearances, he was not at all offended by peculiarities which others mistook for American character, when they were only its accidents; but recognized and did homage to the spectacle of a nation of men working out their destiny without regard to conventionalities, and opening the paths of promotion to the highest honours of the state to the humblest in the community.

But what struck him above all things was their thorough Englishness, if I may use the word. When I walk your streets,"he said at Albany, where he was entertained by the inhabitants of Dutch descent, at the anniversary dinner of their patron saint: - "When I walk your streets, when I enter your houses, I frequently ask myself, 'Do I not feel as if I were still in England?' And I really do feel as if I were still there.I sit atyour tablcs - I see a different description of attendants - !see dishes that are new to me; but the countenances that surround the board - the tongues that I hear - are similar to what I have been familiar with all my life. Everything inyour humanity appears to me to be English. I see the forest of two or three hundred years ago displaced to a distance by a new Liverpool, a new Manchester - by some populous city or another, the inhabitants of which commune in the language which I have spoken from my infancy. I wonder that any of my countrymen can be cross with you - can pick a quarrel with you about straws of peculiarities. You make me prouder of being a British subject - for I am, and ever shall be, proud of being so - you make me prouder of being a British subject than ever I felt before. I know that you or most of you trace your origin to the Dutchman, proverbially the son of enterprise, indefatigability,patience, genius, and bravery; I know that the sentiments and feelings which animated the breasts of your forefathers are now glowing within yours; I trace, or think I trace, in your features and frames, your affinity to your hardy progenitors. Yet, when from your lips I hear the greatest gift, next to the breath of life, bestowed by God on man - the faculty of speech - when I hear that gift,issuing in substantially the same fashion in which it has fallen upon my ear from my childhood, how can I feel othenvise than as if we had sprung from one national mother - how can I but glory more than ever I did in a mother, and that mother my own, which seems to me to be the parent of so multitudinous a progeny as that which you belong to."

As he expressed himself in this speech he expressed himself when he returned to England, not only to strangers but in his own family and good reason he had to speak well of the Americans, for they treated him everywhere with the greatest hospitality.

His first appearance at the Park Theatre, New York, is noticed in a contemporary New York paper thus: - "Nothing could be more gratifying to him than the warm, the affectionate reception he experienced. Unlike the noisy acclamations with which, as a matter of courtesy, a mere actor of European celebrity is received, it was the spontaneous tribute of admiration and respect for one to whose superior genius we have so often.been indebted for amusement and instruction." A cutting from a paper of later date, says: - "The progress of Mr. Sheridan Knowles throughout the United States has been marked with more triumph than, perhaps, ever fell to that of any member of his arduous profession. Not only do the theatres ring with app1ause at each successive representation of the heroes of his own undying tragedies.but he is made welcome as a guest at the public entertainments which take place at the different cities through which he passes." At Philadelphia a banquet was given in his honour, at which Charles Matthews the elder and Tyrone Power were present. New York gave him a "complimentary" benefit, the net proceeds of which amounted to £6oo. Wherever he went he was welcomed and feted. Somehow that feeling of personal regard for him, which mingled with his reputation as a dramatist, and made friends for him even amongst people who had never seen him, had crossed the Atlantic before him, and met him there when he landed. Before he left the deck of the Columbus he was claimed as a guest by a gentleman whom he had never seen before and was carried off to his house with an intimation that it was his own as long as he chose to consider it so. " He is one of the best specimens of the Briton we have had from over the ocean," says. a contemporary journal. "Pity that Englishmen should not send us over more of such men." President Jackson said he had never shaken hands with a European with so much pleasure. Tempting offers were made to him to settle in the States. Land was offered him by more than one of his newly-made friends, and he was further tempted by the assurance that his sons would be placed in the best possible position for making their way in the world. Finally, the patronage he received was so liberal that my mother made frequent visits to the city during his absence to invest his remittances in the Three per Cents; and thus at last realized her long-cherished dream of - money in the bank.

Between his return from America and 1843 he brought out eight more plays of his own (see list below), besides adapting Beaumont and Fletcher's 'Maid's Tragedy' under the name of 'The Bridal,' and iater on the same authors "Noble Gentleman;' the latter, however, was not acted. In 1841 he composed the libretto of a ballad-opera, 'Alexina,' which after his death was re-arranged and brought out as a play under the name, 'True unto Death.' He also wrote tales in the magazines and continued his public lectures. Two novels by him—'George Lovell' and 'Fortescue' —appeared in 1846-7, but neither of them is remarkable. Although he was now in receipt of a comfortable income, his resources were hampered by his ready charity and his chivalrous efforts to discharge his father's debts. In 1848 Knowles was granted a civil-list pension of £200. He was an original member of the committee formed for the purchase of Shakespeare's birthplace at Stratford-on-Avon, and it was reported in 1848, when the purchase was completed, that the custodianship was offered to him. He never filled the office, but at his death the trustees of the birthplace recorded their belief that he had been in receipt of the dividends of £l,000, invested in the names of Forsterand Dickens, for the ostensible purpose of founding a custodianship of the birthplace, and inquiries were made into the investment and appropriation of the dividends (extract from Trustees' Minute-book, 31 Dec. 1862).

Knowles had always had strongly religious and philanthropic interests, and had in early days been greatly impressed by the preaching of Rowland Hill at the Surrey Chapel. About 1844 he embraced an extreme form of evangelicalism and joined the baptists, professing that he had hitherto lived without God and without hope in the world. He delivered sermons from chapel pulpits and at Exeter Hall. He denounced Roman Catholicism, attacked Cardinal Wiseman on the subject of transubstantiation, and wrote two books of controversial divinity; but he avoided preaching against the stage.

He was a great believer in the water-cure. In his last years he visited various parts of the kingdom, and in 1862, soon after entering his seventy-ninth year, was entertained at a banquet in his native city of Cork. On 30 Nov. of the same year he died at Torquay. He was buried in the Necropolis at Glasgow. His first wife died in 1841, and in the following year he married a Miss Elphinstone, a former pupil, who had played Meeta in his 'Maid of Mariendorpt." His son by his first wife, Richard Brinsley Knowles, is noticed separately.

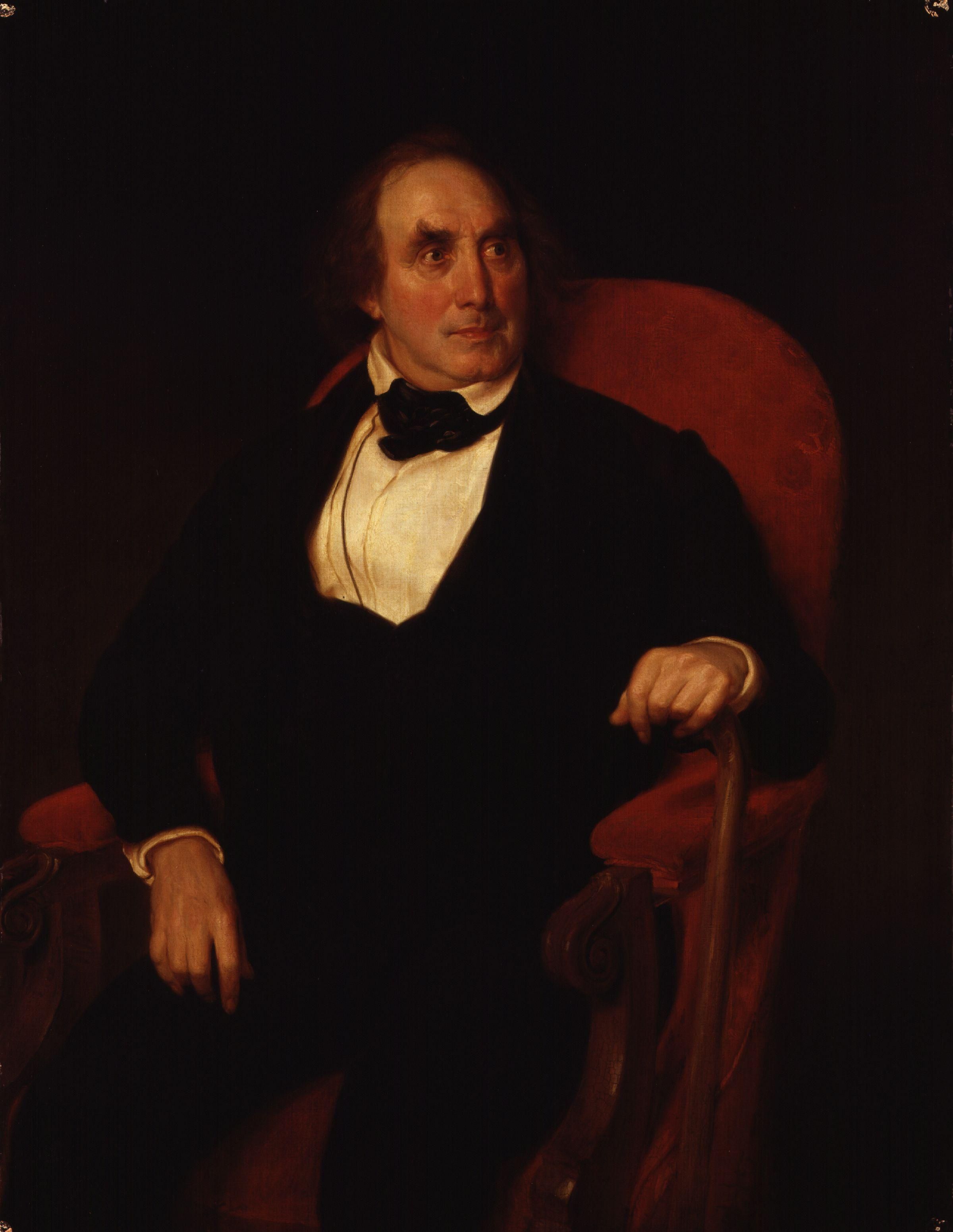

There is a portrait of Knowles in the 'Life' by his son, Richard Brinsley Knowles, and an outline sketch of him in Maclise's Portrait Gallery.

Judged by literary tests alone, Knowles's plays cannot lay claim to much distinction. His plots are conventional, his style is simple, and, in spite of his Irish birth, his humour is not conspicuous. Occasionally he strikes a poetical vein, and his fund of natural feeling led him to evolve many effective situations. But he is a playwright rather than a dramatist. As an actor, his style, from a want of relief and transition, was apt to become tedious, but his unmistakable earnestness strongly recommended him to audiences with whom, as a dramatist, he was in his lifetime highly popular (see Westland MarsTon, Our Becent Actors, ii. 122).

His published works may be conveniently divided into three classes. The dates given are those of first publication.

_____________________________________________

SONGS, POEMS, AND VERSES

BY

Helen, Lady Dufferin (COUNTESS OF GIFFORD)

Edited, with a Memoir and some Account of the Sheridan Family, by her Son THE MARQUESS OF DUFFERIN AND AVA

SECOND EDITION

LONDON

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET

1894

DEC 16 1956

Printed by R. & R. CLARK, Edinburgh

[Pages omitted]

... But those of the Sheridans to whom I have thus briefly referred, are not the only scions of the house who have enriched the literature of their country with works of recognised value; for it will be seen on reference to a table appended to this volume that during the last two hundred and fifty years the family has produced twenty-seven authors and more than two hundred works. Of the collateral contributors to its literary fame I will only mention two: Joseph Thomas Sheridan Lefanu, grandson of Brinsley Sheridan's sister Alicia, who wrote the House by the Churchyard, Uncle Silas, and some other powerful novels, as well as the delightful ballad of "Shamus O'Brien," and Sheridan Knowles, descended from Thomas Sheridan of Quilca, Swift's friend, the author of the Hunchback, a play that still keeps the stage, as well as of other

works and poems of considerable repute.

_________________

Portrait by Daniel Maclise, printed in Patrick Rafroidi, Irish Literature in English, The Romantic Period, 1789-1850, Vol. 1 (1980).

_______________________

QUOTES FROM

JAMES SHERIDAN KNOWLES

Irish dramatist and actor

(1784 - 1862)

Extremes are ever neighbors; 'tis a step from one to the other.

Find earth where grows no weed, and you may find a heart wherein no error grows.

Save the love we pay to heaven, there is none purer, holier, than that a virtuous woman feels for him she would cleave through life to. Sisters part from sisters, brothers from brothers, children from their parents, but such woman from the husband of her choice, never!

The herald, earth-accredited, of heaven,--which when men hear, they think upon heaven's king, and run the items over of the account to which he is sure to call them.

The longest time that man may live,

The lapse of generations of his race,

The continent entire of time itself,

Bears not proportion to Eternity;

Huge as a fraction of a grain of dew

Co-measured with the broad, unbounded ocean!

There is the time of man--his proper time,

Looking at which this life is but a gust,

A puff of breath, that's scarcely felt ere gone!

Wedlock joins nothing, if it joins not hearts.

Women do act their part when they do make their ordered houses know them.

I hear a sound so fine there's nothing lives

'Twixt it and silence-- Virginius (act V, sc. 2) [Sound]

He was buried in the Necropolis at Glasgow. It is only speculation that James Thomas Knowles is James Sheridan Knowles' son.

DEATH AND BURIAL

"On the 29th May, 1862," Sir Joseph Napier writes to my aunt, "he came to see me, and partook of our luncheon. He was joyous and hearty as of old; his eye shone with gladness and his countenance lit up with emotion. But his heart was full of the great subject of the happy change that had come over him, and which he ascribes to the lessons and the prayers of a pious mother. He spoke of a great part of his life as having been a waste for weeds; but that he had learned at last two great truths¬ first, the power of prayer, and next, the infallibility of God's blessed word.

"He felt peace and joy in his heart, and he looked forward with faith and hope to a better and brighter world-a home in heaven.

"He proposed to call on me in London …

"He was not permitted to fulfil his intended visit. The next news I heard of him was that he had entered into his rest. He died in the Lord."

Some little time after this visit to Dublin he went to Glasgow. He had often, in speaking of "the city of his affections," expressed a desire, when his end should come, to be buried there. And now, a very aged man, so changed from the fiery piece of humanity which once bustled along its streets, he visits the Necropolis, and looks around him on the graves of many who had gone before him - some of his " boys " possibly among them - and especially on that of his old friend Stevenson Dalglish. On this same spot - this hill of tombs - he says he would like "to take his own last rest, when his time should come. "It came a few months later; and on the 5th of December, 1862, he was buried on the spot he had selected, some forty friends following him, amongst whom were Robert Dalglish, M.P., Sheriff H. G. Bell, and one of the earliest of his Glasgow "boys," Thomas M. Mackay.

"The mortal remains of this distinguished man," said the" Glasgow Herald" of December 8, "were deposited in the Necropolis of this city on Friday last, in compliance with the wishes of the illustrious deceased.”

Nowhere were the genial qualities of the Irish dramatist more highly appreciated than in this city. Knowles was a universal favourite, not because of his extraordinary abilities, or the fecundity of his genius, but because of his loveable personal attributes. It was the warm and kind¬ hearted man, the fast and steady friend, and the high-minded gentleman, to whom an unworthy thought was absolutely unknown, who forty years ago won the affections of what were then young and generous natures, and who laid the foundations of that reciprocal esteem, of the existence of which we have so recently seen so interesting an illustration."

The grave has seldom closed over any man to whose personal worth there has been so universal a testimony. From the old lady who in his early days said that he needed no other letters of introduction than his face and his heart, down to the tribute I have just quoted, the chain of testimony is absolutely unbroken. And now that I have stood aside, as far as I could, and have left others to speak of him, there is something I would say of him myself, and without which I could not be content to close this volume.

He was deficient in worldly prudence; threw away many good opportunities; undertook unnecessary burdens; acted much, almost mainly upon impulse; was easily imposed upon; and had that defect of character which is understood when we speak of a man being unable to say " No." But we cannot judge of him as of ordinary men. He was so completely sui generis that I cannot say I ever met any one who, in the leading points of his character, even approximately resembled him. He seemed to me¬ and the feeling has grown upon me in retracing my knowledge of him¬ to have lived in the world to a great extent rather as one not quite belonging to it than as a man bearing an earnest and active part in its work. Heaven knows his work was earnest and active enough, but his manner of going through it was unlike that of other men; and, with all his geniality, all his love of his fellow-creatures, all the popularity which his qualities attracted to him, publicly, and still more (if possible) privately, he looked to me as if he stood always apart from his human surroundings, and had in him a radical difference from the rest of men: - as if, in mixing with the world, he came out of an inner world of his own, which more or less is the case with all of us, but which in him was a transit from his habitual world to one to which he did not properly belong.

Perhaps it was in some degree owing to this fact that he carried into advanced age a freshness of sentiment which with men in general seldom survives middle age; and not that only, but a simplicity of character which was almost childlike. The idea, for example, that any one could make up a story for the purpose of robbing him by an appeal to his charity never occurred to him; and if you suggested it, he would tell you to put so ungenerous a notion out of your mind.

Information from Betty Jane Andrews:

Sheridan Knowles was a famous playright in England who graduated from Aberdine University in Scotland. He was poet-lauriet of England and knighted by King George III. His wife was the pinkie (posed for Pinkie, the companion picture to Blue Boy) in Blue Boy by Thomas Gainsborough. It is safe to say, athough no proof exist, that Sheridan Knowles (or his parents or earlier ancestors) had to renounce his Catholic faith to have obtained the education he did and to have received the honors he received from England.

12/18/04 Phone Interview with Elizabeth Jane Early Andrews: "I do recall that Sheridan Knowles, Frances Knowles' uncle, came to America after his conversion to the faith (he did not convert, but his son Richard Brinsley Knowles did). All of his early writings before his conversion were very anti-papist."

Annie Brindle met a woman from Williamsburg, Virginia who said that the one who posed for the Pinkie painting was the aunt of Jane Austin (that Lady Sheridan Knowles, the one in the Pinky painting, was the Aunt of Jane Austin). Lady Sheridan Knowles' father owned a crystal factory in Ireland and she married Lord Sheridan Knowles who was from England and he was the one actually related to Jane Austin. [They may be confusing Lady Sheridan Knowles with Elizabeth Ann Lindley Sheridan.]

____________

EXCERPTS FROM THE LIFE OF JAMES SHERIDAN KNOWLES by his son Richard Brinsley Knowles

Hazlitt about James Sheridan Knowles:

The seeds of dramatic genius are contained and fostered in the warmth of the blood that flows in his veins; his heart dictates to his head. The most unconscious, the most unpretending, and the most artless of mortals, he instinctively obeys the impulses of natural feeling, and produces a perfect work of art. He has hardly read a poem or a play, or seen anything of the world, but he hears the anxious beatings of his own heart, and makes others feel them by the force of sympathy. Ignorant alike of rules, regardless of models, he follows the steps of truth and simplicity; and strength, proportion, and delicacy are the infallible results. By thinking of nothing but his subject, he rivets the attention of the audience to it. All his dialogue tends to action; all his situations form classic groups. There is no doubt that 'Virginius' is the best acting tragedy that has been produced on the modern stage. … There is no impertinent display, no flaunting poetry; the writer immediately conceives how a thought would tell if he had to speak it himself. Mr. Knowles is the first tragic writer of the age; in other respects he is a common man, and divides his time and affections between his plots and his fishing tackle; between the Muses' spring and those mountain streams.

Leigh Hunt once said to me, "No one could see your father in a room or on the stage without at once saying, 'That is a remarkable man.'"

...that sparkle like his own eye; that gush out like his own voice at the sight of an old friend. We have known him almost from a child, and we must say he appears to us the same boy-poet that he ever was. He has been cradled in song, and rocked in it as in a dream, forgetful of himself and of the world."

The italics in this extract are mine. I have made them because they recall my father to me, in some of his words, so perfectly. And if it were my duty to state what, in my opinion, was the main source of his success as a dramatist, I do not think I could do better than repeat the words - "He bears the anxious beatings of his own heart, and makes others feel them by the force of sympathy."

From the "Glasgow Herald," shortly after my father's death, in a letter written by "an Old Pupil”:

"James Sheridan Knowles! How my heart warms at the name of that single-minded and enthusiastic son of genius! For more than two years I was a member of his elocution class in Glasgow; and I look backward to the days which I spent under his tuition as amongst the brightest and most genial of my life. To become a pupil of Knowles' was to become in a great measure his adopted child. He loved his 'boys' with an affection greatly analogous to that of a father, nor was his kindness ever thrown away. We never looked upon him in the light of a task-exacting pedagogue. There was not one of us who would not have gone through fire and water for 'Old Knowles' or 'Paddy Knowles,' as in loving familiarity we called him, almost to his face. The sternest chastisement which he could inflict upon offenders was to debar them from the school-room for a given number of days. In other seminaries holidays are the reward of merit and diligence; with us they were regarded as penalties.

"Though in the receipt of a considerable income from class fees, Knowles in process of time slipped into the quagmire of poverty. This untoward state of things was not attributable either to extravagance or dissipation. In the words or a fellow-countryman and kindred spirit -

'Even his failings lean'd to virtue's side.'

Never could he hear unmoved the tale of sorrow or the supplication of penury. His last shilling was ever at the service of the man who could make out a plausible case of hardship or of want. Unfortunately, the designing and fraudulent took advantage too often of the generally-known temperament of the poet, and shoals of sordid leeches were ever ready to fasten upon him whenever he had a guinea in his purse. Much of the money thus disbursed was nominally in the shape of loans; but, as the lender seldom exacted acknowledgments of debt, the coin might as well in most cases have been buried in the recesses of the 'Dominie's Hole.'"

His habit was to write as much as possible in the open air and he would leave home after an early breakfast and stroll along the Newhaven sands with his book and pencil, returning to a four o'clock dinner, after which he would read to my mother what he had written, and then walk up to Edinburgh to attend his classes there. I well remember those evenings: - my mother sitting in her invalid chair, feeble after a long illness, my father reading to her what he had written during the day, dwelling hopefully on the progress of his work, and expressing his confidence of success. Of a morning he would sometimes take his younger sons down with him to the beach, and help them to sail a large yacht-rigged boat, and in sailing which, I believe, he took as much pleasure as they did. Indeed be was always ready to put his hand to any work of this kind to amuse us, and I remember his turning boat-builder himself on one occasion for my benefit, and making and rigging for me a lugger of which I was becomingly proud. Many a game at marbles did he play with us; many a kite was the work of his hands. He took especial delight in encouraging and directing our juvenile attempts at gymnastics, and whilst we lived at Edwin Place, near Glasgow, he put one of his sons on skates when he was seven years old, and trained him himself. He held that a boy’s amusements are as important a part of his education as his lessons.

The "Spectator" prefaces its criticism of the actor by giving a portrait of the man: -

"If we wished to see the model of a manly, open-hearted, generous fellow, Mr. Knowles is his image; somewhat coarse, perhaps,-a little provincial too; but there he stands- a broadside of integrity and manliness -a pyramid of strength and burliness; yet by the eye and the softening of the manner one in whom may be detected a gentle and affectionate spirit, a tender and inflammable heart.... His evident want of familiarity with the stage, his occasional failures in attempts at mouthing, and sometimes his straight-forward business-like procedure, more than once gave us great delight; we said, here is a natural man on the stage, going through his part as if he were on the great stage of the world. But for the true part of a hunchback, be he benevolent or malignant, he has too many burly perfections; and in working it out he wants concentratedness, calmness, and the consciousness of power. What he did in this way - for now and then he assumed the imposing - had too much the formal air of an elocutionist showing how the thing should be done."

There was something fearless, modest, generous, and real, about Mr. Knowles' deportment that won us completely; and the whole occurrence put the man and the house upon a familiar and sincere footing, that we like, but have never seen before. It was not one of his majesty's servants cringing to a tyrant public, but an artist facing his friends and fellow men. It was Ben Johnson in the nineteenth century."

One more scene yet I must record in that night's performances. It took place before no audience, and amid no waving of hats and handkerchiefs. "'How did you feel at the moment when your victory had reached its culminating point?' 'I cannot tell you what I felt,' was the reply. 'But I shall tell you what I did. As soon as they let me away from the front, I ran trembling and panting to my dressing-room, and bolting the door, I sank down on my knees, and from the bottom of my soul thanked God for his wondrous kindness to me. I was thinking on the bairns at home, my boy; and if ever I uttered the prayer of a grateful heart, it was in that little chamber.'"

I believe it was the bitterest regret of his last years, that he had spent so much of life 'without God, and without hope in the world.' It was a constant source of abasement, that while familiar with all the knowledge of which men boast, he had yet remained in darkness about God, and without receiving into his heart the love of God in Christ his Saviour.

On death of his son, Dr. James Knowles:

Amongst my father's many Glasgow friends was Captain Thomas Blair, of the Hon. East India Company's navy. One night after they had supped together prior to Captain Blair's starting the next day on a voyage to Calcutta, as they were bidding each other good-bye, Blair placed in my father's hands a roll of bank-notes, with these words: "If we never meet again, Knowles, regard this as a legacy." It was £500. Some time before this, seeing my father struggling with a large family, and being himself a bachelor and very wealthy, he offered to adopt one of his sons, and provide for him. But you might as well ask my father to give you his heart out of his breast as to part, even to such a friend and on such terms, with one of his children. So that offer went off. "Well, then," said Blair, "bring up your eldest son to the medical profession, and as soon as he is qualified, I will get him an appointment in my own ship."

That sealed my brother's fate for the medical profession. As soon as he had passed his examinations, my father received from another friend the offer of an appointment for him, as head surgeon on board one of the king's ships. He at first accepted it; but, on second thoughts, doubted the propriety of placing so young a man in so responsible a position, and declined it. Shortly aftenwards my brother was appointed assistant surgeon to the "William Fairlie," H.E.I.C.S.; and in his first voyage in 1832, reached Calcutta, and died of fever.

I shall never forget the occasion when the news reached us. We had been anxiously expecting a letter, and one day my father took me with him to the city to make enquiries. His first visit was to an office where he was known. There was no letter; and it was clear there never would be one as soon as the gentleman who saw him said, "I don't know whether you are aware that there has been a good deal of sickness on board." That was enough. My father just managed to say, "Has anything happened to my son?" The answer, "I don't know," did not deceive him. As soon as he got into the street he burst into tears. ''Your brother is dead," he said to me; and with his heart bursting, he went weeping along the streets till we reached another office, where, not knowing who he was, a clerk showed him the last list of the ship's company, with the entry, "James Knowles-dead."

Not a word or a look of all this has passed from my memory, for his death was the first death, except of infant children, which had happened in our family, and we were all very fond and proud of him. And no wonder, for he was a lion-hearted young fellow, and a fine specimen of manly strength and beauty. The thought of fear never entered his mind, nor of self if any one needed help. Walking with him on the pier at Newhaven, one day when the tide was in, he suddenly threw down his hat and stick and dived. I looked down and saw a dark body struggling in the water near the bottom. In a few seconds my brother brought it to the surface. It was an idiot lad, who had fallen off the ledge of the pier, and would certainly have been drowned but for this interposition. On another occasion, at the same place, he saved the life of a man who was taken with cramp while bathing. He swam out to him and brought him to shore. Again at Newhaven, while rowing with two fellow students, an oar broke, or was lost, and there not being a spare one, the boat, which was sharp at both ends, was unmanageable. In this perplexity they lowered their anchor, while my brother stripped and, though the boat was more than a mile from shore, swam to land, got an oar, and swam back with it.

He was at that time finishing his medical studies at Edinburgh. The students bad been annoyed by a pugilist who amused himself with insulting and then thrashing them if they showed fight. Unluckily one day he fell foul of a student who knew something of sparring, and was not to be trifled with. "If," said my brother, "you were a gentleman I should require from you the satisfaction of a gentleman." [The stupid practice of dueling was not then out of fashion, and there had been more than one duel just then amongst the students.] As you are a pugilist I will take you in your own way. Meet me in the meadows at six this evening." They met, and after a fight which lasted an hour and twenty minutes, the fellow went home with a sound thrashing, and cured, for the time at least, of his ruffianly propensity.

But a pluckier thing still, and which was the talk of all the schools in Glasgow the day after, was his charging, single handed, a company of curlers [Curling is simply the game of bowls played upon the ice, the curling stone being flat-bottomed instead of round, and grasped by a bent handle. It is not an instrument with which a skater would like to come into collision], and rescuing from them a young student who would othewise have fared badly at their hands. We had been skating on Middleton Pond, near Glasgow, but after a while my brother took off his skates, strapped them up, and walked up and down the bank watching the others. It was thawing, and the curlers having worn out the ice at their end of the pond, came to ours and began to play there. This was very unfair and excited much indignation amongst the skaters, one of whom, a spirited young fellow, took his stand upon the line of play they had marked out, and swore with an oath that the game should not go on. One of the curlers said he would soon settle that. He took the curling stone and was about to drive it at the skater, when the latter finding his position untenable, began to stamp with all his might upon the ice in order to destroy its surface, and spoil the game which he saw he could not prevent. This bare statement of the thing gives no idea of the extent to which blood was up on both sides. The rage and excitement were intense, and when the curlers saw they were likely to be baffled they rushed upon him, and he, instead of giving them leg bail upon the ice, as he easily could have done, most injudiciously made a rush for the bank, and ran crippled by his skates till they overtook him in a field close by, knocked him down and began to belabour him.

My brother, who was standing with me a little way off, had taken no part in all this, nor did he approve of the skater's temerity, which he thought rash, nor of his flight, which he thought fatal. But now he took a part in it with a vengeance. Dashing in amongst them he laid about him right and left with his skates with such surprising effect that in less than a minute the curlers were ftying across the field in every direction. It was really a fine thing to see a lad between nineteen and twenty, "like an eagle in a dove-cot," not "fluttering" the fellows of whom there were not less than a dozen, but sending them scampering off like so many hares. No doubt he wielded an effective weapon, but it was risky work for all that, and if the men had stood their ground and rallied he could have had no chance with them. The onslaught however with which he came crashing down upon them was so sudden, unexpected, and fierce, that they were seized with panic. It was sauve qui peut in a moment; but the victor lost his hat in the melee, and had to walk back to Glasgow with his handsome curly head bare.

Neither my father nor mother had any favourites amongst us: but, as their first child, the companion of their early days of poverty, he must necessarily have had some preference in their affections, and it was an awful blow to them to lose him just as they had started him in life with such good prospects, and when they were preparing to welcome him back to a home which had been so brightened by prosperity in the interval of his absence. He was not to see it. After spending some weeks in Calcutta with Captain Blair, he returned to the ship, took jungle fever from an officer whom he attended and cured. The physician could not cure himself. One day, Captain Blair, who had meantime resumed the command, went into his cabin and sat with him. He said he felt that the worst was over and that he should now rapidly recover. Presently he expressed a desire to sleep, and in that sleep he died.

As for the subject of this memoir I can say, looking back to my earliest recollection of him (Sheridan Knowles) and the impressions made upon my mind from my childhood upwards with regard to him, that I have rarely known a man who had a stronger sense of religion, deeper veneration for it, or who carried out its precepts more in the practice of his life. Therefore if we must speak of his "conversion," let us clearly understand what sort of conversion we mean.

It was certainly not that of the flagrant sinner whose life has been a scandal to his neighbours, and whose heart by some touch of grace has been suddenly melted into penitence. Nor was it that of the "respectable" sinner perfectly correct in his exterior, but whose heart might as well have been made of putty for all the loving kindness that ever came out of it. Few men ever went through the rough work of sixty years so free from reproach. That character which comes nearest to that of "Christian" the character of "gentleman" - he had filled so as to win for himself

"Golden opinions from all sorts of people."

No man was more considerate of the feelings of others, which I take to be a main note of both characters; nor more upright in his dealings, more straight forward, more sensitively honourable, more incapable of meanness or injustice. He was not perfect, any more than the rest of us, but of none could it be more truly said that his faults-vices he had none, nor the shadow of a vice-were the excess of his virtues. His acts of generosity were habitual. If he saw merit pining in the shade, it rejoiced him to help it into the light. He was a fast friend and stood by those he loved all the more staunchly if they happened to be in trouble. Of his plays, it is not enough to say that they are free from objection; they never fail to inculcate a high tone of morality, and even, occasionally of religion. I have shown to what practical use, when a very young man, he turned Rowland Hill's preaching; and I can vouch for him that both by example and precept he strenuously aided my mother's pious efforts to give her children a Christian education. Another mark of the Christian and gentleman I see in his chivalrous respect for women and in the purity of his conversation. With him in all sorts of companies, -literary, theatrical, professional; amongst merchants, manufacturers, sea-captains, or what not, I never heard an impure expression from his lips. We have here then, I submit, a very fair Christian to begin with; and if we are bound to speak of the change which took place in him somewhere about his sixtieth year, as a "conversion," we must qualify the term by bearing in mind that it produced in him neither a sudden nor a very great alteration. It was rather a development of what he was already than the substitution of something new, and it by no means justifies the statement in the sermon already quoted that he spent sixty years of his life "without true religion."

One phase of it, indeed, was a total departure from his antecedents. We have seen how large was the heart of his youth and middle age 1 - how warmly he advocated the cause of Catholic emancipation; and how in his days of struggle and poverty he could find time to lecture for the Roman Catholic poor schools of Glasgow. Earnest he was in those days in his own faith; not indifferent to the obligations it imposed upon him as a citizen and the head of a household; yet putting his creed into practice by acts of kindliness to all whom he could befriend without asking whether at their morning and evening devotions they knelt before a crucifix or the back of a bed-room chair. That is not the man we have now to contemplate. Instead of lecturing for Catholic poor schools, he will lecture on the Errors of Popery to raise funds for the Irish Church Missions. He no longer believes that the Papist can be loyal to the throne or inherit salvation, but regards him as a tool in the hands of a designing priesthood, working for the overthrow of the constitution under which he lives, and especially for the damnation of his own soul. I am not putting this too strongly. I state it at all very much against my will. But as a faithful chronicler I am bound to say that after his conversion no one cried, "No Popery!" louder than he did - in his books, on the platform, in the pulpit, or in private conversation.

But here again we find in him a thorough sincerity. Whatever their value as contributions to sacred literature, his two controversial books, and his essay on the Gospel of St. Matthew, evince strong convictions, and were not produced without great industry. Of the former, the first published was the "Rock of Rome; or, the Arch-Heresy." It combats the position that St. Peter was the head of the Apostles, and denies that he was ever at Rome. In the second, "The Idol demolished by its own Priest," -he proposes to refute a work of his late Eminence Cardinal Wiseman on the Holy Eucharist.

Though he lost all patience in speaking of popes and cardinals, there was some thing very affecting in the gentle, endearing way in which, after an animated invective, he would ask you for your soul's health to lay aside your own convictions and adopt his. And, again, if like myself you were a Catholic and happened to dine with him on a Friday he would have the best fish to be got for your dinner...

But his conversion had other fruits than controversy; it did not, as I maintain, produce a change of heart, but it converted a man of strong religious feelings into one who became all-absorbed by them. Religion had never been absent from his thoughts; was never named by him without reverence. I do not believe the sun ever rose or set upon him in all his life that he did not pay the Christian's homage to his Creator; it was only the fulfilment of a strong probability that, with advancing years, he came to think more often and more earnestly of the solemn "hereafter,'" and resolved that thenceforth this thought alone should occupy his mind, to the exclusion, as far as possible, of every other. That he did so with sincerity I have the best reason, apart from the impossibility of his doing anything otherwise, for knowing. When an offer was made to him through myself of £500 for a novel, a sum which would have been very acceptable to him at the time, he wrote to me, "I have put my hand to the plough and will not turn back." Other evidences were not wanting: the resignation, for example, with which he bore the physical sufferings of his latter years, and his detachment from the interests of life. But upon this subject it may be better that I let others speak.