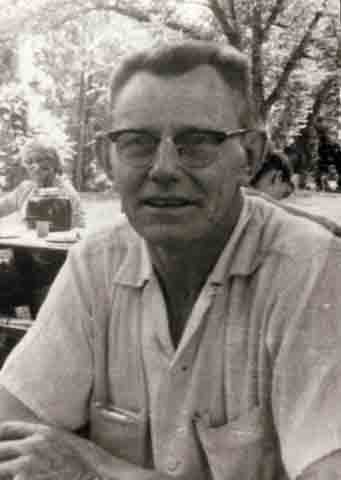

The eighth child and third son of Joseph L. and Millie Jane [Davis] McLain, was born August 9, 1909 at their farm on "Gander Hill" in New Buda Township, Decatur County, Iowa. "Gander Hill" is a story in itself, in essence the name was derived from Millie Jane keeping geese using their feathers for mattresses and pillows.

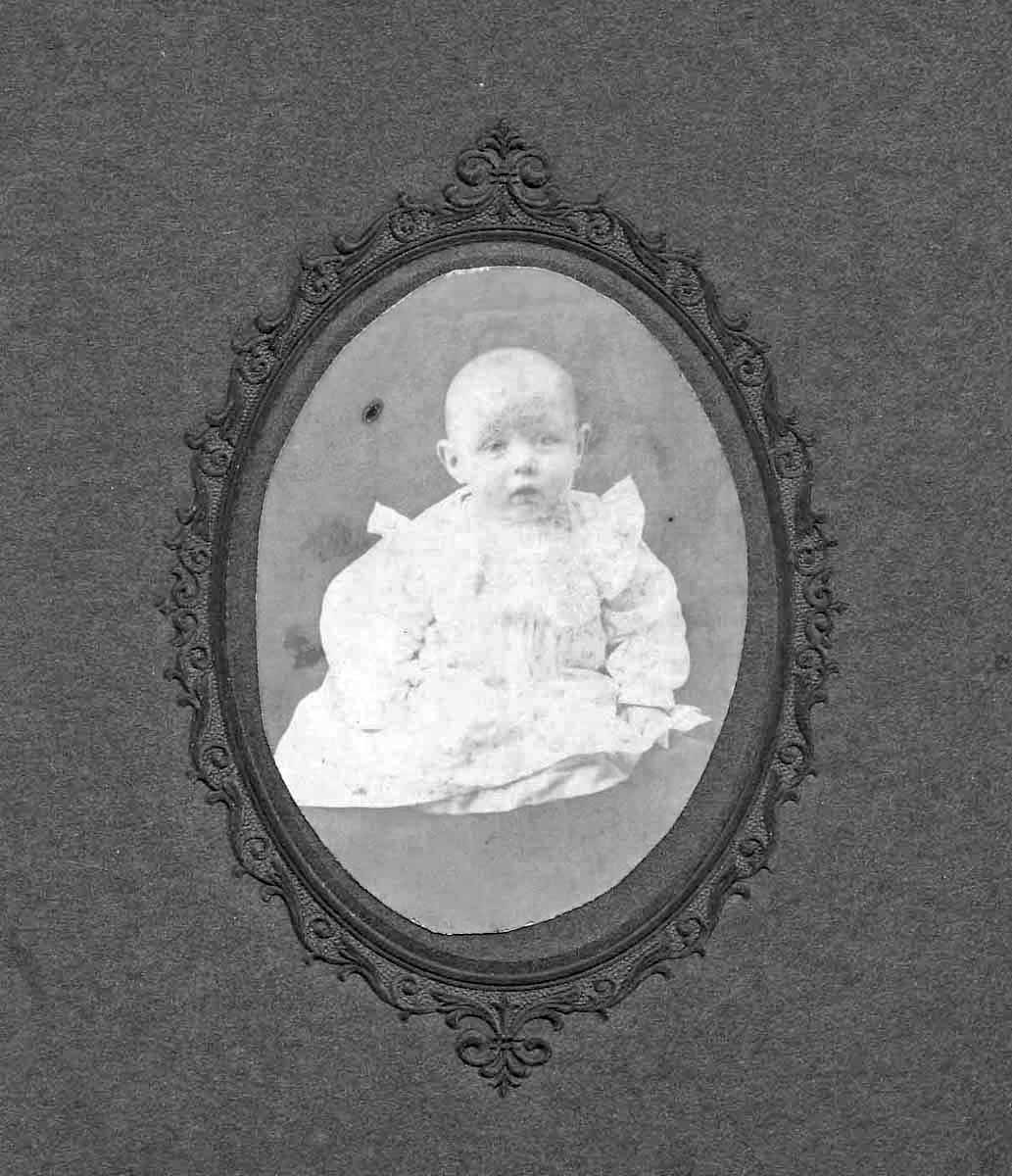

According to his sister, Berdie [McLain] Ordway "my kid brother was born in the east room upstairs on the farm. He weighed 9 pounds and born on the hottest day of the year. His aunt, Ida Davis, came to assist her sister-in-law and placed the newborn in the south bedroom where there was a cool breeze. He was so cute, Veta and I loved to hold him."

The parents, however, could not decide on a name. After a long discussion, Dr. J. B. Horner, the attending physician from Lamoni, Iowa, decided that if they couldn't decide he would call him Joseph after the father. In the official Decatur County birth records he was listed as Joseph. The parents were still undecided. When the 1910 census was enumerated on April 27, 1910 he was referred to as "Unnamed son." His father gave everybody nicknames and his became "Towd" as an abbreviated form of "Towhead" a term used for blondes. He was known as "Towd" for the rest of his life among his parents, siblings and Decatur county residents. He moved to Des Moines in 1942 and if anyone saw him and referred to him as "Towd" you knew immediately where they were from.

In the 1920 census, his name is William S. It is possible, but he never admitted that he detested the name William due to his cousin on a neighboring farm shared the same name. William or Bill, nicknamed "Babe" was retarded and spent his adult life in the euphemistically expression "show business" or otherwise as a carnival worker. A post card from his brother Charles, who was in the army during World War I, was addressed to William S. McLain, Davis City, Iowa.

Some might say that he might have been lucky to survive until the 1920 census. In January of 1913, his grandfather, Adam, was deathly ill. Joseph and his son Charles drove him to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN. He was suffering from stomach cancer and was diagnosed as being so ill that he might not survive the trip back to Davis City. Instead they took him to the home of his daughter, Bertie [McLain] Ruppert in LeMars, IA where he died on the 14th of January. When Joe returned home he laid his coat over a chair and went to bed. Towd was in the crib bed in the same room. His father often brought candy for them when he returned from trips. Towd woke up and saw that his father was home and saw the coat lying across the chair. He climbed out of the crib and searched the coat for candy. Instead he found his grandfather's medicine. He became restless. His dad told him to go to sleep. Irritated, his parents got up to find out what was wrong with him. His throat was swollen out to his chin. They managed to get him to the doctor in time to save him.

His two brothers, Charlie [12] and Jim [9], were sufficiently older so his playmates were his sister Madge and a niece, Ferne, who was a year younger. Between the two girls they always had him in trouble. He wasn't afraid to try anything they dared him to do. If anything went wrong of their devices he was the one to get punished.

As Berdie Ordway writes, "He was full of curiosity. He wanted to know why the babies rattler rattled; why a clocked ticked; a pump pumped water when you moved the handle and a light came on when you pulled the string." [He had to visit his Uncle Lyman in town as the farm didn't have electricity until the late 1940's] He was determined to find the answers and this usually got him in trouble. She continues, "He severed a finger, excepting a tiny bit of skin in a corn-sheller. His grandmother, Cynthia Wood, held it in place until Dr. Reed came and sewed the finger back in place to save it. The doctor told him if he wouldn't cry he would take him for a ride in his new car. This turned out to be an empty promise." She doubts that it kept him from finding out how the corn-sheller works.

Another time, "He was at the wind-mill watching the pump jack pumping water. Somehow he got his arm between the two cogwheels. He was lucky that his arm wasn't severed between the wrist and elbow. It was bleeding so profusely that he reached down and got a handful of dirt, packed it on the wound and stopped the bleeding." He saved the arm and Berdie often wondered if his mother ever got all the dirt out of the wound.

When he was a teenager he once went roller-skating with his cousin, Jimmy McLain. Shortly after arriving at the rink, Towd was no where to be found. On closer inspection they found him in a dark corner of the rink with his back to the wall. No amount of coaxing would bring him out of his corner. Later, he admitted that he had fallen and tore the seat out of his pants.

A more serious incident occurred with Jimmy after his parents moved into town. Towd stayed on the farm with his brother Charles and his wife Opal so that he could stay in school. He and Jimmy were about 12 and were playing with a spray pump at Jimmy's house. They filled the pump with gasoline. Towd lit a match as Jimmy pumped. Jimmy turned and sprayed Towd directly in the face. Towd couldn't see so Jimmy led him to the railroad tracks and he crawled into town and fearing his father's anger hid in the barn. Berdie went out to gather eggs and found him hiding in the barn. His face was a solid blister, water bags of skin were hanging down over his eyes. Somehow, this healed without leaving any scars on his face.

He often said that he spent six years in the 8th grade. In fact he spent six years in a one-room schoolhouse with eight grades. Unofficially, he dropped the name William and used his middle name Stephen.

Nothing had deterred his curiosity. He was still taking things apart and amazed everyone when he got it back together. When he was 13 the family owned two Model T's. His father was the self-appointed driving instructor for Davis City and would often chauffeur people all over the country. Steve investigated the inner workings of both cars and disassembled both. One can imagine his father's displeasure when he found this out and was just as pleasantly surprised when he put them back together. The latter part wasn't communicated to him directly.

Steve knew by the time that he was 17 that he had no interest in farming. Charlie and Jim had seniority and he got all the dirty jobs. Charlie and Jim didn't exactly have it easy either. Later, with the promise of 40 acres for himself, he wanted no part of his heritage. His sister, Veta had married Wade Hanie and had moved to Kansas City, MO. This looked like a promising opportunity so he went there as well. He was convinced that there was no job that he couldn't do and claimed experience in everything. He convinced a hotel manager that he could handle the telephone switchboard, when in fact he had never seen a switchboard. Within an hour he was a bellhop.

He eventually went back home to the farm. Not to farm, but to work occasionally with his father and Charlie, learned about electricity and carpentry. Jobs were either nil to scarce in Decatur County in the 1930's as they were in other parts of the country. In order to raise farm price on livestock the government slaughtered animals indiscriminately and buried them in open trenches along the roadside without compensation. Everyone had to pitch in just to survive and if possible-save the farm. The government then came in and offered 70-year low interest loans to help out.

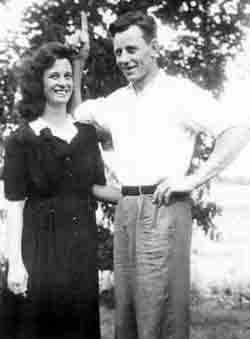

Steve was doing a quite a bit of work in the county seat of Leon. He was applying his newly gained skills in construction. Leon is eight miles from Davis City. There were always kids waiting for the school bus as he was going to work. Steve knew one of the kids, Elmer Reynolds, and offered him a ride to school. He couldn't take him without taking his siblings as well. There were four others going to the same school. One of which was Retha. Day after day they would be waiting to go to school and Steve obliged by taking them to school. After Retha graduated, they began dating and in November 1932 were married in the parsonage of the Brethren church in Leon. The father-in-law gave her the nickname of Peggy. After their marriage Steve was working on the electrical high-lines throughout Iowa. Peggy moved to the farm on Gander Hill and soon became pregnant. Steve's job would keep him away for weeks at a time.

The question arose about his given name. Fearing that his child would be considered illegitimate he went to the courthouse and had his name officially changed from Joseph [as the doctor had entered it] to Stephen. So after 24 years he finally got a name, officially. According to 'Peggy,' "Millie Jane," his mother, "insisted that Stephen's name was supposed to be Stephen Joseph," but this never made it into official records.

Dad was working at a variety of jobs, including the high-lines, Civilian Conservation Corps [CCC] and the WPA. After Wayne was born in 1933 at the farm on "Gander Hill," the family moved to a rented house in Leon, IA. I was born there in 1935. When work was real scarce, dad even resorted to taking a job as a farm laborer when several families in Decatur County went to northern Iowa to help with the harvest. Mom wrote to her sons who were left behind in Leon with Grandma Reynolds "That even the alleys in Ida Grove were so clean and they don't even use jailbirds." This was the standard fare for Decatur County.

Dad took advantage of an opportunity to learn welding at Des Moines Technical High school at night in 1941. Before he completed his training World War II had started. He immediately got a job with the Des Moines Steel Company. He was to spend the rest of his working career as welder, maintenance and finally tool crib manager. It was his versatility and mechanical knowledge that helped with his promotions. Pittsburgh Steel Company bought out the Des Moines Steel Company. When they discovered that he could repair pneumatic jacks, instead of throwing them away, they started sending tools from their other plants to Des Moines for him to repair. Both companies were involved in constructing framework for bridges, buildings and water towers. This included the framework for the St. Louis Arch.

This same mechanical knowledge affected his home life as well. Relatives, neighbors and co-workers would bring their cars to the house for him to fix. On rare occasions he would even get paid. Normally someone would bring over a six-pack and help him drink it while he fixed their cars. Otherwise it was a grateful thank you. He was ingratiating to all and found it difficult to refuse anyone.

Wayne and I were more interested in playing ball then watch dad work and get all greasy in the garage. We didn't spend as much time with him as we should have. On Friday nights Wayne and I would go to the movies with all the other kids. This was the usual ritual. We first had to ask permission to go to the show. It would go like this: "Mom can we go to the Show?" "Ask your Dad" "Dad can we go to the show?" "What did your Mother say?" "She said to ask you." Dad was usually in the garage. "I don't care if she doesn't." Once securing permission we had to repeat the procedure to get the money to go. It didn't take long for me to get tired of this process. I started mowing yards, carrying newspapers to earn my own money. This made it easier for Wayne to obtain his funds.

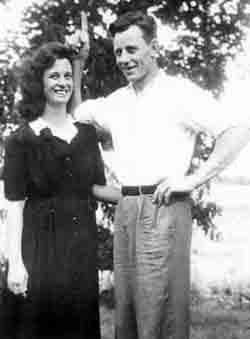

Dad never seemed comfortable in conversations with his children. He seldom asked questions. Never volunteered to attend social activities. Reticent in giving anyone advice. In a group he would seldom speak out and voice his opinion. In his own way he would find a way to speak to everyone in the group privately. Due to lung cancer he had a lung removed at the Iowa Lutheran Hospital in 1972. We went to visit him there and he introduced us to all the patients in his wing and called them all by name.

Wayne and I found out second-handed that Dad was proud of our accomplishments in sports through his co-workers. He never attended any of our games and had no in-depth knowledge of our activities. His co-workers would keep him informed. Brothers, Michael [1946] and Jim, [1948] were to benefit more as his working on cars begin to diminish. He managed to devote more attention to their activities. Other than playing an occasional game of horseshoes or playing cards, I don't think he ever participated in sports.

He was very private. He wasn't a joiner of organizations other than the United Steel Workers and served on the Board of Directors for their local. He did join the Moose Lodge in Burlington, IA so that he could go with his father-in-law and have a few drinks when he visited there. To my knowledge he never attended the Moose Lodge in Des Moines.

When someone was in need he was there to help. His mother-in-laws' house burned down in Leon, IA. May Vanhorn Reynolds' house was 70 miles south of Des Moines. On weekends, holidays and vacations he would go and help rebuild her house. He persuaded his brother Charles and a brother-in-law, Wilbur Baker to help. His sister Madge wanted a basement excavated under the existing house and he was there to do it. Wayne and I learned to drive using a 1933 Plymouth to spread the dirt around the yard that dad bought just for this purpose. Another sister Veta lived a short distance from him and he helped them remodel their home. Most of his life he did what was expected of good citizens, work, help others and be a good neighbor.

When he died, February 9, 1973, Hamilton Funeral home mentioned that it was one of the largest funerals that they had ever conducted for a non-personality. Pittsburgh-Des Moines Steel didn't close the plant in Des Moines, but allowed any employee who wanted to attend without loss of pay. We talked to the superintendent, Don Binks, afterwards, and he said they sould have shut down as almost everyone went to the funeral. The motor procession was bumper to bumper for well over a mile in length and wound from the east side of Des Moines to Sunset Memorial cemetery in the southwestern part of the city. All of this was to honor a man that asked nothing for himself and was several years without a name.

The eighth child and third son of Joseph L. and Millie Jane [Davis] McLain, was born August 9, 1909 at their farm on "Gander Hill" in New Buda Township, Decatur County, Iowa. "Gander Hill" is a story in itself, in essence the name was derived from Millie Jane keeping geese using their feathers for mattresses and pillows.

According to his sister, Berdie [McLain] Ordway "my kid brother was born in the east room upstairs on the farm. He weighed 9 pounds and born on the hottest day of the year. His aunt, Ida Davis, came to assist her sister-in-law and placed the newborn in the south bedroom where there was a cool breeze. He was so cute, Veta and I loved to hold him."

The parents, however, could not decide on a name. After a long discussion, Dr. J. B. Horner, the attending physician from Lamoni, Iowa, decided that if they couldn't decide he would call him Joseph after the father. In the official Decatur County birth records he was listed as Joseph. The parents were still undecided. When the 1910 census was enumerated on April 27, 1910 he was referred to as "Unnamed son." His father gave everybody nicknames and his became "Towd" as an abbreviated form of "Towhead" a term used for blondes. He was known as "Towd" for the rest of his life among his parents, siblings and Decatur county residents. He moved to Des Moines in 1942 and if anyone saw him and referred to him as "Towd" you knew immediately where they were from.

In the 1920 census, his name is William S. It is possible, but he never admitted that he detested the name William due to his cousin on a neighboring farm shared the same name. William or Bill, nicknamed "Babe" was retarded and spent his adult life in the euphemistically expression "show business" or otherwise as a carnival worker. A post card from his brother Charles, who was in the army during World War I, was addressed to William S. McLain, Davis City, Iowa.

Some might say that he might have been lucky to survive until the 1920 census. In January of 1913, his grandfather, Adam, was deathly ill. Joseph and his son Charles drove him to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN. He was suffering from stomach cancer and was diagnosed as being so ill that he might not survive the trip back to Davis City. Instead they took him to the home of his daughter, Bertie [McLain] Ruppert in LeMars, IA where he died on the 14th of January. When Joe returned home he laid his coat over a chair and went to bed. Towd was in the crib bed in the same room. His father often brought candy for them when he returned from trips. Towd woke up and saw that his father was home and saw the coat lying across the chair. He climbed out of the crib and searched the coat for candy. Instead he found his grandfather's medicine. He became restless. His dad told him to go to sleep. Irritated, his parents got up to find out what was wrong with him. His throat was swollen out to his chin. They managed to get him to the doctor in time to save him.

His two brothers, Charlie [12] and Jim [9], were sufficiently older so his playmates were his sister Madge and a niece, Ferne, who was a year younger. Between the two girls they always had him in trouble. He wasn't afraid to try anything they dared him to do. If anything went wrong of their devices he was the one to get punished.

As Berdie Ordway writes, "He was full of curiosity. He wanted to know why the babies rattler rattled; why a clocked ticked; a pump pumped water when you moved the handle and a light came on when you pulled the string." [He had to visit his Uncle Lyman in town as the farm didn't have electricity until the late 1940's] He was determined to find the answers and this usually got him in trouble. She continues, "He severed a finger, excepting a tiny bit of skin in a corn-sheller. His grandmother, Cynthia Wood, held it in place until Dr. Reed came and sewed the finger back in place to save it. The doctor told him if he wouldn't cry he would take him for a ride in his new car. This turned out to be an empty promise." She doubts that it kept him from finding out how the corn-sheller works.

Another time, "He was at the wind-mill watching the pump jack pumping water. Somehow he got his arm between the two cogwheels. He was lucky that his arm wasn't severed between the wrist and elbow. It was bleeding so profusely that he reached down and got a handful of dirt, packed it on the wound and stopped the bleeding." He saved the arm and Berdie often wondered if his mother ever got all the dirt out of the wound.

When he was a teenager he once went roller-skating with his cousin, Jimmy McLain. Shortly after arriving at the rink, Towd was no where to be found. On closer inspection they found him in a dark corner of the rink with his back to the wall. No amount of coaxing would bring him out of his corner. Later, he admitted that he had fallen and tore the seat out of his pants.

A more serious incident occurred with Jimmy after his parents moved into town. Towd stayed on the farm with his brother Charles and his wife Opal so that he could stay in school. He and Jimmy were about 12 and were playing with a spray pump at Jimmy's house. They filled the pump with gasoline. Towd lit a match as Jimmy pumped. Jimmy turned and sprayed Towd directly in the face. Towd couldn't see so Jimmy led him to the railroad tracks and he crawled into town and fearing his father's anger hid in the barn. Berdie went out to gather eggs and found him hiding in the barn. His face was a solid blister, water bags of skin were hanging down over his eyes. Somehow, this healed without leaving any scars on his face.

He often said that he spent six years in the 8th grade. In fact he spent six years in a one-room schoolhouse with eight grades. Unofficially, he dropped the name William and used his middle name Stephen.

Nothing had deterred his curiosity. He was still taking things apart and amazed everyone when he got it back together. When he was 13 the family owned two Model T's. His father was the self-appointed driving instructor for Davis City and would often chauffeur people all over the country. Steve investigated the inner workings of both cars and disassembled both. One can imagine his father's displeasure when he found this out and was just as pleasantly surprised when he put them back together. The latter part wasn't communicated to him directly.

Steve knew by the time that he was 17 that he had no interest in farming. Charlie and Jim had seniority and he got all the dirty jobs. Charlie and Jim didn't exactly have it easy either. Later, with the promise of 40 acres for himself, he wanted no part of his heritage. His sister, Veta had married Wade Hanie and had moved to Kansas City, MO. This looked like a promising opportunity so he went there as well. He was convinced that there was no job that he couldn't do and claimed experience in everything. He convinced a hotel manager that he could handle the telephone switchboard, when in fact he had never seen a switchboard. Within an hour he was a bellhop.

He eventually went back home to the farm. Not to farm, but to work occasionally with his father and Charlie, learned about electricity and carpentry. Jobs were either nil to scarce in Decatur County in the 1930's as they were in other parts of the country. In order to raise farm price on livestock the government slaughtered animals indiscriminately and buried them in open trenches along the roadside without compensation. Everyone had to pitch in just to survive and if possible-save the farm. The government then came in and offered 70-year low interest loans to help out.

Steve was doing a quite a bit of work in the county seat of Leon. He was applying his newly gained skills in construction. Leon is eight miles from Davis City. There were always kids waiting for the school bus as he was going to work. Steve knew one of the kids, Elmer Reynolds, and offered him a ride to school. He couldn't take him without taking his siblings as well. There were four others going to the same school. One of which was Retha. Day after day they would be waiting to go to school and Steve obliged by taking them to school. After Retha graduated, they began dating and in November 1932 were married in the parsonage of the Brethren church in Leon. The father-in-law gave her the nickname of Peggy. After their marriage Steve was working on the electrical high-lines throughout Iowa. Peggy moved to the farm on Gander Hill and soon became pregnant. Steve's job would keep him away for weeks at a time.

The question arose about his given name. Fearing that his child would be considered illegitimate he went to the courthouse and had his name officially changed from Joseph [as the doctor had entered it] to Stephen. So after 24 years he finally got a name, officially. According to 'Peggy,' "Millie Jane," his mother, "insisted that Stephen's name was supposed to be Stephen Joseph," but this never made it into official records.

Dad was working at a variety of jobs, including the high-lines, Civilian Conservation Corps [CCC] and the WPA. After Wayne was born in 1933 at the farm on "Gander Hill," the family moved to a rented house in Leon, IA. I was born there in 1935. When work was real scarce, dad even resorted to taking a job as a farm laborer when several families in Decatur County went to northern Iowa to help with the harvest. Mom wrote to her sons who were left behind in Leon with Grandma Reynolds "That even the alleys in Ida Grove were so clean and they don't even use jailbirds." This was the standard fare for Decatur County.

Dad took advantage of an opportunity to learn welding at Des Moines Technical High school at night in 1941. Before he completed his training World War II had started. He immediately got a job with the Des Moines Steel Company. He was to spend the rest of his working career as welder, maintenance and finally tool crib manager. It was his versatility and mechanical knowledge that helped with his promotions. Pittsburgh Steel Company bought out the Des Moines Steel Company. When they discovered that he could repair pneumatic jacks, instead of throwing them away, they started sending tools from their other plants to Des Moines for him to repair. Both companies were involved in constructing framework for bridges, buildings and water towers. This included the framework for the St. Louis Arch.

This same mechanical knowledge affected his home life as well. Relatives, neighbors and co-workers would bring their cars to the house for him to fix. On rare occasions he would even get paid. Normally someone would bring over a six-pack and help him drink it while he fixed their cars. Otherwise it was a grateful thank you. He was ingratiating to all and found it difficult to refuse anyone.

Wayne and I were more interested in playing ball then watch dad work and get all greasy in the garage. We didn't spend as much time with him as we should have. On Friday nights Wayne and I would go to the movies with all the other kids. This was the usual ritual. We first had to ask permission to go to the show. It would go like this: "Mom can we go to the Show?" "Ask your Dad" "Dad can we go to the show?" "What did your Mother say?" "She said to ask you." Dad was usually in the garage. "I don't care if she doesn't." Once securing permission we had to repeat the procedure to get the money to go. It didn't take long for me to get tired of this process. I started mowing yards, carrying newspapers to earn my own money. This made it easier for Wayne to obtain his funds.

Dad never seemed comfortable in conversations with his children. He seldom asked questions. Never volunteered to attend social activities. Reticent in giving anyone advice. In a group he would seldom speak out and voice his opinion. In his own way he would find a way to speak to everyone in the group privately. Due to lung cancer he had a lung removed at the Iowa Lutheran Hospital in 1972. We went to visit him there and he introduced us to all the patients in his wing and called them all by name.

Wayne and I found out second-handed that Dad was proud of our accomplishments in sports through his co-workers. He never attended any of our games and had no in-depth knowledge of our activities. His co-workers would keep him informed. Brothers, Michael [1946] and Jim, [1948] were to benefit more as his working on cars begin to diminish. He managed to devote more attention to their activities. Other than playing an occasional game of horseshoes or playing cards, I don't think he ever participated in sports.

He was very private. He wasn't a joiner of organizations other than the United Steel Workers and served on the Board of Directors for their local. He did join the Moose Lodge in Burlington, IA so that he could go with his father-in-law and have a few drinks when he visited there. To my knowledge he never attended the Moose Lodge in Des Moines.

When someone was in need he was there to help. His mother-in-laws' house burned down in Leon, IA. May Vanhorn Reynolds' house was 70 miles south of Des Moines. On weekends, holidays and vacations he would go and help rebuild her house. He persuaded his brother Charles and a brother-in-law, Wilbur Baker to help. His sister Madge wanted a basement excavated under the existing house and he was there to do it. Wayne and I learned to drive using a 1933 Plymouth to spread the dirt around the yard that dad bought just for this purpose. Another sister Veta lived a short distance from him and he helped them remodel their home. Most of his life he did what was expected of good citizens, work, help others and be a good neighbor.

When he died, February 9, 1973, Hamilton Funeral home mentioned that it was one of the largest funerals that they had ever conducted for a non-personality. Pittsburgh-Des Moines Steel didn't close the plant in Des Moines, but allowed any employee who wanted to attend without loss of pay. We talked to the superintendent, Don Binks, afterwards, and he said they sould have shut down as almost everyone went to the funeral. The motor procession was bumper to bumper for well over a mile in length and wound from the east side of Des Moines to Sunset Memorial cemetery in the southwestern part of the city. All of this was to honor a man that asked nothing for himself and was several years without a name.

Family Members

-

![]()

Mary Edith McLain Ambrassat

1890–1984

-

![]()

Esther Grace McLain Fitzwater

1894–1996

-

![]()

Charles Lewis "Charlie" McLain

1897–1994

-

![]()

Nellie Beatrice McLain Fitzwater

1899–1942

-

![]()

James Adam McLain

1901–1988

-

![]()

Berdie Irene McLain Ordway

1903–2003

-

![]()

Veta Viola McLain Hanie

1905–1992

-

![]()

Madge Marie McLain Ballentyne Rue

1912–2006

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement