Weste Harris was a younger son of David Golightly Harris & Emily Jane Lyles Harris of Golightly, SC a few miles south of Spartanburg, an agricultural area named after his great-grandfather Christopher Golightly who was one of the first white settlers and landowners here before the Revolutionary War. Published in 1900, John Landrum's history of Spartanburg County has a small headshot of Christopher, and a short biography stating he was a fine upstanding Christian man, though Landrum mentioned he was "eccentric". Christopher's fine house still stands near where Weste was born and grew up. Christopher's daughter Elizabeth Golightly probably met her future husband James Harris of NC during the Revolutionary War when the revolutionaries encamped nearby and fought a battle against the Redcoats on what is now the land of the Cedar Springs School for the Deaf and the Blind a few miles to the north. I suspect that her father Christopher, like many big landowners, gave shelter and sustenance to the men who were assembling along the path of the British Redcoats who were advancing northward in their march from Charleston, SC to join up with the British in the Northeast. The British lost their first big battle with the Patriots at Kings Mountain shortly after they passed thru this area.

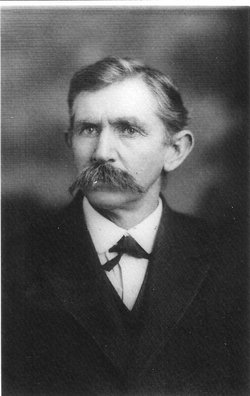

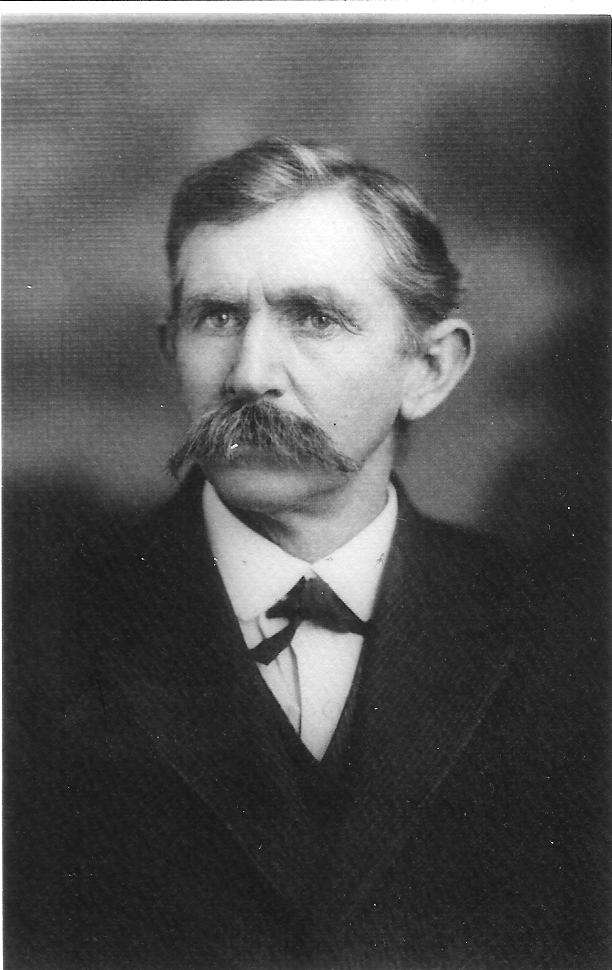

Weste was known as a succinct man of few words who read a lot. He was homeschooled by his mother Emily Jane Liles Harris, who was unusually for her day the product of a highly-rated finishing school & an excellent writer, samples of which writing still exist in the journal they kept during the 1850's-70's. Weste was known as a highly progressive farmer, skills which combined both his parents' strong focus on education and agricultural knowledge.

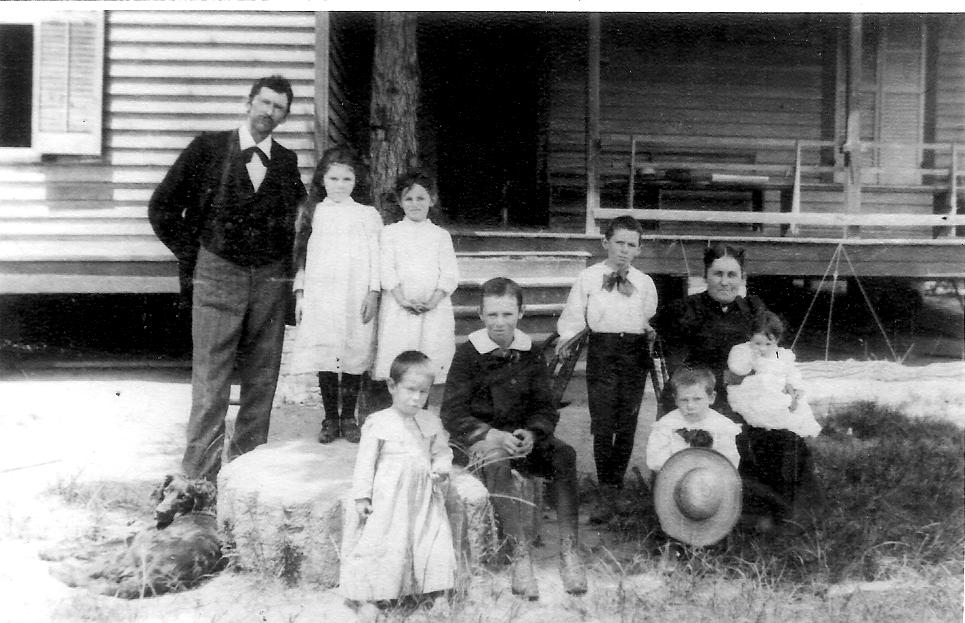

Weste married the oldest daughter of the county sheriff, Harriet Caroline "Hattie" Gentry, whom he met when they were both baptized on the same day at the (First) Baptist Church of Spartanburg. (It was the first of many Baptist Churches but was not labeled 'first' until years later.) Hattie's rich father Sheriff Landon Miles Gentry was said to have disapproved of his oldest daughter marrying a poor country farmer's son, but Miles eventually gave them land next to the Southern Railway's Shops north of Spartanburg, where they raised 9 out of 10 children, all but one of whom graduated from college & all but one of whom became teachers.

Weste was said by his daughter Hattie Weste to be an emotionally low-key man who never raised his voice or got angry when his children made mistakes in contrast to his wife who often whipped the children for minor unintentional infractions, he was a practical and well-rounded self-educated man and somewhat of a jack-of-all-trades. Weste once set the compound-fractured arm of his daughter, who was playing on the roof & fell off, and he had basic brickmasonry and carpentry skills. When recounting her father to me, Hattie Weste said that when she would do something wrong, her mother would whip her with a hickory switch which would hurt, but the physical pain would not last & would have no positive impact on her behavior. But if her father would take her on his knee & start explaining what she did wrong, by the time he finished she would be crying & would understand why what she had done was wrong, & thus she would never want to do it again. Hattie Weste, needless to say, adored her father.

Hattie Weste was first called Hattie Bess according to her father's grandfather clock where he wrote the names and birth dates of all the children, but she said she later changed Bess to Weste in honor of her closeness to her favorite parent.

Weste was known as an accomplished farmer, teaching himself advanced farming methods by reading and experimenting, he was a Mason & also a senior member of the Ku Klux Klan when it was at it's height in the 1920's according to his granddaughter Marjorie Foster Jameson, who said she recognized him during a Klan meeting by a crooked little finger which was broke and never healed straight. He raised his family on land given to them by his father-in-law and he built his own home which he added to as his family grew. At one point Weste removed the roof of the house & built a 2nd floor, and later he built himself a study off to the side where he kept his library and fiddled on his violin away from his wife who my mother said did not at all enjoy fiddling, he was away sometimes attending fiddling conventions and owned several violins, one of which is now in the possession of his grandson John Edwin Foster, he had hand carved a case for his favorite violin out of the stump of a walnut tree, and it was said to fit so snugly it would not shake when moved. That violin was given to him by an old black man who fiddled at his wedding, and then presented to him the violin as his wedding gift, telling him that now it was his time to learn.

Weste learned farming from both his parents and steadily improved on his parents' knowledge, reading up on the modern techniques and becoming known as a very progressive farmer. His mother had a fruit orchard & vegetable garden, and his father raised large cash crops like oats and wheat before & during the Civil War on their small plantation south of Spartanburg at Golightly, SC, about halfway between Spartanburg & Pauline. They had some slaves and his father also managed his sisters land and slaves as well as his own which was adjacent to his. His journal details the farm life they lived on this upstate plantation which was much smaller than lowcountry plantations. The upstate plantations were not as large and did not have as many slaves due to land and climate differences. His father's journal has many comments about farm life and the general happenings, he started the journal as just a factual record of the farm, but he changed more and more as time went on to talking about the family and the current events of the day. When his father was gone in the Confederate army, his mother Emily took over the journal and kept up with events. Emily's writing is striking, it is more evocative of feelings and shows a strong awareness of her own strong emotions. She did not like being left in charge of the slaves, who were becoming sullen and stealing.

Weste did not receive a school education, very few people did then, and his father wrote they lived too far from the town to attend city schools, before the Civil War there were no free public schools, only a few boarding schools, so his father was trying to hire a schoolteacher for the school he built just before the Civil War, but his only schoolteacher did not stay but a few months and his wife Emily was highly educated and he pointedly praised her homeschooling for all their children. (From the way he wrote, I suspect they used the journal as a method of communication between the two of them.) Weste's father David was a prodigious reader & writer himself & also became a Baptist preacher near the end of his life as the pastor of Philadelphia Baptist in Pauline a few miles to the south; both his parents highly valued education and Weste and his wife continued the path his parents had laid by sending all their children to higher education.

In 1908, Weste Harris was honored with the appointment as Spartanburg County's very first County Demonstration Agent, a new national position, he was put in charge of showing farmers how to better their crop yields using modern scientific methods. It was a prestigious job which unfortunately they decided required a higher education degree, so he only held the job for 4 years while they paid for a local boy to attend the Clemson Agricultural College. His daughter Emily told me that after the newly graduated young man took over his job, Weste and his wife Hattie had to teach him basic farming techniques because he did not have much practical experience, she said she remembered them coming inside shaking their heads over his ignorance. Weste was a skilled farmer, he had earned the County Demonstration Agent position by cross-pollinating & grafting a new type of apple which he named the Harris apple; Weste had taken a bushel of the Harris apples to the state agricultural convention in 1907 & gained himself an article in The State newspaper, which was reprinted in the Spartanburg Herald & the Spartanburg Journal. (Unfortunately, his apple orchard later burned to the ground during a brush fire according to his grandson J Edwin Foster, so his hybrid apple did not survive.) During this job, which lasted four yrs, Weste emphasized positive environmental practices, encouraging people to love the land. One of the innovations he started was the County Fair contests which were extremely popular during the 1900's into the 1960's, people would come from all over the county in October to enter their best homemade jams & quilts & farm livestock for a ribbon & hopefully a cash prize & get their names printed in the newspaper; it greatly increased the respectability of the fair which until then had been known mostly for drunkenness & gambling.

Weste felt strongly about respecting the land & taking care of it & using it wisely, he urged the planting of trees in the town as a way of cooling off the hot summer days, personally planting a row of oak trees along Reidville Rd, some of which are still there today 100 years later. My mother said that Weste had a personal motto that before he would decide to cut down any tree, he would watch that tree grow for 10 yrs; he emphasized respect for nature, trees were so valuable to society & took so many years to mature, he wanted people to realize they had a life span as long as a human being; Once cut, a tree would take decades to replace. Weste surrounded his own home with large oak trees which lined the long driveway to his house, his daughter Emily said the shade underneath the trees would be 10-15 degrees cooler in the summertime.

In his free time, Weste was an avid fiddler, often attending fiddler's conventions, his interest in fiddling had begun when the old Negro man who played at his wedding then offered him his fiddle as a wedding present, a great honor as it was his most valuable possession. Weste carved a solid case for that fiddle out of the stump of a walnut tree, & the fit was so snug the fiddle would not shake about. (The fiddle is now in the possession of his grandson John Edwin Foster.) When at home, Weste would fiddle off in a study he had built for himself off the main house, he would close the door so as not to irritate his wife. Weste would often buy & sell fiddles, one story goes that he was at a fiddler's convention when a man approached him at the break with an offer to buy his fiddle. Since this was the fiddle the old Negro man had given him at his wedding, Weste refused. The well-dressed man was insistent, saying he'd heard that fiddle over all the other fiddlers playing & he wanted that mellow-sounding fiddle. Weste refused to sell again. At this point, the would-be buyer brought out his checkbook & offered Weste a blank check for the fiddle, saying he could write his own price, but he again refused. When Weste returned home & told his family of the encounter, his frugal wife, disgusted, is said to have responded, "Today, two fools met."

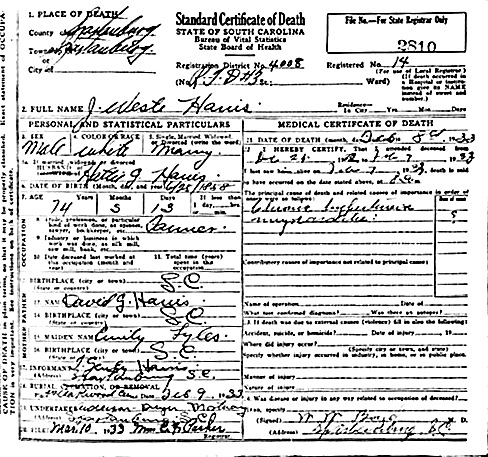

In later years, Weste was getting dementia which several of his children also suffered from, he was described as "eccentric" to me by two of his grandchildren who knew him. He died at home, two years before his son Gentry committed suicide. (Weste's mother Emily Lyles Harris had often complained of emotional problems, possibly bipolar disorder, several of her descendants have been diagnosed with bipolar & depression.) Weste was described by my grandmother as a very even-tempered man, she said he never lost his temper or raised his voice to anyone, and when he spoke, he was frugal with words, succinct. He evidently succumbed to a heart condition listed as chronic myocarditis when he died in the home he had built.

Children of Weste Harris

Lyles, the oldest of Weste Harris's surviving sons, became a missionary to Africa in 1912 after graduating from Clemson Mechanical & Agricultural College in 1909 with degrees in both Agriculture & Chemistry, he became a progressive farmer like his father, growing cotton in the British Colony of Kenya in the early 1920's after the 'Great War' in Europe where he fought on the English side. He traveled widely before he returned to America in 1925 and then he managed several farms in NC in the 1930's to 1950's; he also edited a newspaper in Franklin, NC & managed a hotel in Blowing Rock, NC with his English wife Jan who was a British nurse; my mother said Jan nursed him back to health during a terrible sickness when he almost died during the war. They had 2 sons.

Weste Harris's son John Weste Harris, Jr, who had worked in military intelligence during WWI according to his sister Mella, was a graduate of Wofford College & also taught there after making straight A's, he became a lawyer, teacher & businessman, but his most public contribution to society was the National Beta Club. The National Beta Club recognizes high school children for their ability to maintain a B average in school. John was said to have gotten the idea from a friend who died, a Mr Green, according to his sister Mella, she said John never gave his friend credit for the very worthy organization, one of many complaints she had about John's behavior.

F Gentry Harris graduated from Wofford, then graduated from Columbia University law school in NYC, he became a very famous local lawyer and was head of the Federal Land Bank and the Principal of West End School. The year before Gentry committed suicide in 1935 in his law office on Morgan Square, he was listed in the 1934 edition of "Who's Who In SC". He left behind a wife & 3 children and a mother & siblings who deeply mourned his loss. My mother told me his long suicide note began: "I'm tired, tired, tired, and I want to rest." My mother related that her mother Hattie Weste said that Gentry had always been his mother's right hand, she often sent him when young to collect rent from the many rental properties she had inherited from her father, whom she took care of at the end of his life. Hattie Weste said she believed her mother put too much responsibility on his young shoulders. Gentry was blind in one eye from amblyopia, an hereditary condition in which a child is born with one eye either very nearsighted or farsighted, his sister Mella said it kept him from being drafted in the Great War, which angered him. Gentry was so eager to serve that eventually the commandant of Camp Wadsworth gave him the job of water boy which Mella said pleased him greatly.

Son Carlos died in 1926 from wounds suffered in France in The Great War in 1918. Carlos was a 1st Lieutenant and commanded a black fighting unit which was highly commended during the war for bravery. Carlos also graduated from Clemson Mechanical and Agricultural College, he was the editor for the Clemson school newspaper in his senior year & I'm recently told by a Clemson graduate doing a book on Clemson veterans that he organized the senior dance that year as well as being the captain of the basketball team. Carlos later graduated from Columbia Univ's law program in 1925 & passed the bar in NY, but he never practiced law, he joined McClellan's Dept. Store & managed their store in Iowa during the last year of his life until infection from his hip injury caused septicemia; he died in the New York Veteran's Hospital with his brother John by his side. John accompanied his body home to Spartanburg on the train, the newspaper article and his nephew Edwin said the funeral was so large that the police had to cordon off Main Street around the First Baptist Church for several blocks to accommodate all the attendees. Carlos is buried in the Oakwood family plot with his parents, he left no wife or children.

Daughters Hattie, Julia, Emily & Mella all became K-12 teachers in the Spartanburg school system; Hattie was first a private family governess, then taught grades 1-6 at Poplar Springs Elementary before she retired to raise 7 children; Julia became a Spartanburg public school history teacher & the family genealogist & raised 4 children; Emily taught 1st & 2nd grade & raised 3 children; Mella first taught physical education, and then switched to English, she retired from Cleveland Junior High School in 1969; her students remembered her as a tough and effective teacher; she never had any children but she took over the care of two nieces during the Depression and sent them to Converse College. All the children but Mella and Carlos married & all but Carlos, Mella & Joe had families. Mella told me once that nursing & teaching were considered the only 'respectable' jobs open to women at that time, she made it clear that she would've loved to have had a different career, particularly as a novelist.

Weste's youngest child Joe graduated from Clemson's world-famous agricultural program, then went to work for the Southern Railroad near his family home; he married twice but my mother said he had a physical defect and could not have children. Both his wives were named Lyda Mae. I remember Joe near the end of his life as a big jolly man with a very deep powerful voice that quite literally shook the house when he laughed, he reminded me of Santa. He died of a strange ailment that the many doctors he consulted could not diagnose, my mother said she believed he had lead poisoning from painting boxcars.

NOTE:

The marker on the Harris plot in West Oakwood cemetery is the main grist mill stone that came from Weste Harris's father David Golightly Harris's grist mill in Golightly, which was chronicled in his journal, transcribed & printed under the name "A Piedmont Farmer" by Wofford College professor Dr. Philip Racine. Weste's daughter Mella Harris had 3 grist mill stones, this one was the main stone. She also possessed the 2 other smaller stones from the grist mill which I remember sitting in her front yard near the sidewalk. Mella told me the local stonemasons refused at first to use the big stone because they believed it was too heavy to move. One finally agreed, but only if they could drill a large hole into the middle to hoist it up by crane. Mella thought this quite ironic since men had cut & moved this same stone several times in the 1800's-1900's with much more primitive technology. The monument is very distinctive & unique. The plot is in West Oakwood, next to the present-day Converse University playing field. Hattie Gentry Harris's parents are buried nearby, as are several of Weste & Hattie's children. Mella told me that West Oakwood was reserved for members of the elite of Spartanburg, she was quite proud her family was buried there.

--Jeni

Weste Harris was a younger son of David Golightly Harris & Emily Jane Lyles Harris of Golightly, SC a few miles south of Spartanburg, an agricultural area named after his great-grandfather Christopher Golightly who was one of the first white settlers and landowners here before the Revolutionary War. Published in 1900, John Landrum's history of Spartanburg County has a small headshot of Christopher, and a short biography stating he was a fine upstanding Christian man, though Landrum mentioned he was "eccentric". Christopher's fine house still stands near where Weste was born and grew up. Christopher's daughter Elizabeth Golightly probably met her future husband James Harris of NC during the Revolutionary War when the revolutionaries encamped nearby and fought a battle against the Redcoats on what is now the land of the Cedar Springs School for the Deaf and the Blind a few miles to the north. I suspect that her father Christopher, like many big landowners, gave shelter and sustenance to the men who were assembling along the path of the British Redcoats who were advancing northward in their march from Charleston, SC to join up with the British in the Northeast. The British lost their first big battle with the Patriots at Kings Mountain shortly after they passed thru this area.

Weste was known as a succinct man of few words who read a lot. He was homeschooled by his mother Emily Jane Liles Harris, who was unusually for her day the product of a highly-rated finishing school & an excellent writer, samples of which writing still exist in the journal they kept during the 1850's-70's. Weste was known as a highly progressive farmer, skills which combined both his parents' strong focus on education and agricultural knowledge.

Weste married the oldest daughter of the county sheriff, Harriet Caroline "Hattie" Gentry, whom he met when they were both baptized on the same day at the (First) Baptist Church of Spartanburg. (It was the first of many Baptist Churches but was not labeled 'first' until years later.) Hattie's rich father Sheriff Landon Miles Gentry was said to have disapproved of his oldest daughter marrying a poor country farmer's son, but Miles eventually gave them land next to the Southern Railway's Shops north of Spartanburg, where they raised 9 out of 10 children, all but one of whom graduated from college & all but one of whom became teachers.

Weste was said by his daughter Hattie Weste to be an emotionally low-key man who never raised his voice or got angry when his children made mistakes in contrast to his wife who often whipped the children for minor unintentional infractions, he was a practical and well-rounded self-educated man and somewhat of a jack-of-all-trades. Weste once set the compound-fractured arm of his daughter, who was playing on the roof & fell off, and he had basic brickmasonry and carpentry skills. When recounting her father to me, Hattie Weste said that when she would do something wrong, her mother would whip her with a hickory switch which would hurt, but the physical pain would not last & would have no positive impact on her behavior. But if her father would take her on his knee & start explaining what she did wrong, by the time he finished she would be crying & would understand why what she had done was wrong, & thus she would never want to do it again. Hattie Weste, needless to say, adored her father.

Hattie Weste was first called Hattie Bess according to her father's grandfather clock where he wrote the names and birth dates of all the children, but she said she later changed Bess to Weste in honor of her closeness to her favorite parent.

Weste was known as an accomplished farmer, teaching himself advanced farming methods by reading and experimenting, he was a Mason & also a senior member of the Ku Klux Klan when it was at it's height in the 1920's according to his granddaughter Marjorie Foster Jameson, who said she recognized him during a Klan meeting by a crooked little finger which was broke and never healed straight. He raised his family on land given to them by his father-in-law and he built his own home which he added to as his family grew. At one point Weste removed the roof of the house & built a 2nd floor, and later he built himself a study off to the side where he kept his library and fiddled on his violin away from his wife who my mother said did not at all enjoy fiddling, he was away sometimes attending fiddling conventions and owned several violins, one of which is now in the possession of his grandson John Edwin Foster, he had hand carved a case for his favorite violin out of the stump of a walnut tree, and it was said to fit so snugly it would not shake when moved. That violin was given to him by an old black man who fiddled at his wedding, and then presented to him the violin as his wedding gift, telling him that now it was his time to learn.

Weste learned farming from both his parents and steadily improved on his parents' knowledge, reading up on the modern techniques and becoming known as a very progressive farmer. His mother had a fruit orchard & vegetable garden, and his father raised large cash crops like oats and wheat before & during the Civil War on their small plantation south of Spartanburg at Golightly, SC, about halfway between Spartanburg & Pauline. They had some slaves and his father also managed his sisters land and slaves as well as his own which was adjacent to his. His journal details the farm life they lived on this upstate plantation which was much smaller than lowcountry plantations. The upstate plantations were not as large and did not have as many slaves due to land and climate differences. His father's journal has many comments about farm life and the general happenings, he started the journal as just a factual record of the farm, but he changed more and more as time went on to talking about the family and the current events of the day. When his father was gone in the Confederate army, his mother Emily took over the journal and kept up with events. Emily's writing is striking, it is more evocative of feelings and shows a strong awareness of her own strong emotions. She did not like being left in charge of the slaves, who were becoming sullen and stealing.

Weste did not receive a school education, very few people did then, and his father wrote they lived too far from the town to attend city schools, before the Civil War there were no free public schools, only a few boarding schools, so his father was trying to hire a schoolteacher for the school he built just before the Civil War, but his only schoolteacher did not stay but a few months and his wife Emily was highly educated and he pointedly praised her homeschooling for all their children. (From the way he wrote, I suspect they used the journal as a method of communication between the two of them.) Weste's father David was a prodigious reader & writer himself & also became a Baptist preacher near the end of his life as the pastor of Philadelphia Baptist in Pauline a few miles to the south; both his parents highly valued education and Weste and his wife continued the path his parents had laid by sending all their children to higher education.

In 1908, Weste Harris was honored with the appointment as Spartanburg County's very first County Demonstration Agent, a new national position, he was put in charge of showing farmers how to better their crop yields using modern scientific methods. It was a prestigious job which unfortunately they decided required a higher education degree, so he only held the job for 4 years while they paid for a local boy to attend the Clemson Agricultural College. His daughter Emily told me that after the newly graduated young man took over his job, Weste and his wife Hattie had to teach him basic farming techniques because he did not have much practical experience, she said she remembered them coming inside shaking their heads over his ignorance. Weste was a skilled farmer, he had earned the County Demonstration Agent position by cross-pollinating & grafting a new type of apple which he named the Harris apple; Weste had taken a bushel of the Harris apples to the state agricultural convention in 1907 & gained himself an article in The State newspaper, which was reprinted in the Spartanburg Herald & the Spartanburg Journal. (Unfortunately, his apple orchard later burned to the ground during a brush fire according to his grandson J Edwin Foster, so his hybrid apple did not survive.) During this job, which lasted four yrs, Weste emphasized positive environmental practices, encouraging people to love the land. One of the innovations he started was the County Fair contests which were extremely popular during the 1900's into the 1960's, people would come from all over the county in October to enter their best homemade jams & quilts & farm livestock for a ribbon & hopefully a cash prize & get their names printed in the newspaper; it greatly increased the respectability of the fair which until then had been known mostly for drunkenness & gambling.

Weste felt strongly about respecting the land & taking care of it & using it wisely, he urged the planting of trees in the town as a way of cooling off the hot summer days, personally planting a row of oak trees along Reidville Rd, some of which are still there today 100 years later. My mother said that Weste had a personal motto that before he would decide to cut down any tree, he would watch that tree grow for 10 yrs; he emphasized respect for nature, trees were so valuable to society & took so many years to mature, he wanted people to realize they had a life span as long as a human being; Once cut, a tree would take decades to replace. Weste surrounded his own home with large oak trees which lined the long driveway to his house, his daughter Emily said the shade underneath the trees would be 10-15 degrees cooler in the summertime.

In his free time, Weste was an avid fiddler, often attending fiddler's conventions, his interest in fiddling had begun when the old Negro man who played at his wedding then offered him his fiddle as a wedding present, a great honor as it was his most valuable possession. Weste carved a solid case for that fiddle out of the stump of a walnut tree, & the fit was so snug the fiddle would not shake about. (The fiddle is now in the possession of his grandson John Edwin Foster.) When at home, Weste would fiddle off in a study he had built for himself off the main house, he would close the door so as not to irritate his wife. Weste would often buy & sell fiddles, one story goes that he was at a fiddler's convention when a man approached him at the break with an offer to buy his fiddle. Since this was the fiddle the old Negro man had given him at his wedding, Weste refused. The well-dressed man was insistent, saying he'd heard that fiddle over all the other fiddlers playing & he wanted that mellow-sounding fiddle. Weste refused to sell again. At this point, the would-be buyer brought out his checkbook & offered Weste a blank check for the fiddle, saying he could write his own price, but he again refused. When Weste returned home & told his family of the encounter, his frugal wife, disgusted, is said to have responded, "Today, two fools met."

In later years, Weste was getting dementia which several of his children also suffered from, he was described as "eccentric" to me by two of his grandchildren who knew him. He died at home, two years before his son Gentry committed suicide. (Weste's mother Emily Lyles Harris had often complained of emotional problems, possibly bipolar disorder, several of her descendants have been diagnosed with bipolar & depression.) Weste was described by my grandmother as a very even-tempered man, she said he never lost his temper or raised his voice to anyone, and when he spoke, he was frugal with words, succinct. He evidently succumbed to a heart condition listed as chronic myocarditis when he died in the home he had built.

Children of Weste Harris

Lyles, the oldest of Weste Harris's surviving sons, became a missionary to Africa in 1912 after graduating from Clemson Mechanical & Agricultural College in 1909 with degrees in both Agriculture & Chemistry, he became a progressive farmer like his father, growing cotton in the British Colony of Kenya in the early 1920's after the 'Great War' in Europe where he fought on the English side. He traveled widely before he returned to America in 1925 and then he managed several farms in NC in the 1930's to 1950's; he also edited a newspaper in Franklin, NC & managed a hotel in Blowing Rock, NC with his English wife Jan who was a British nurse; my mother said Jan nursed him back to health during a terrible sickness when he almost died during the war. They had 2 sons.

Weste Harris's son John Weste Harris, Jr, who had worked in military intelligence during WWI according to his sister Mella, was a graduate of Wofford College & also taught there after making straight A's, he became a lawyer, teacher & businessman, but his most public contribution to society was the National Beta Club. The National Beta Club recognizes high school children for their ability to maintain a B average in school. John was said to have gotten the idea from a friend who died, a Mr Green, according to his sister Mella, she said John never gave his friend credit for the very worthy organization, one of many complaints she had about John's behavior.

F Gentry Harris graduated from Wofford, then graduated from Columbia University law school in NYC, he became a very famous local lawyer and was head of the Federal Land Bank and the Principal of West End School. The year before Gentry committed suicide in 1935 in his law office on Morgan Square, he was listed in the 1934 edition of "Who's Who In SC". He left behind a wife & 3 children and a mother & siblings who deeply mourned his loss. My mother told me his long suicide note began: "I'm tired, tired, tired, and I want to rest." My mother related that her mother Hattie Weste said that Gentry had always been his mother's right hand, she often sent him when young to collect rent from the many rental properties she had inherited from her father, whom she took care of at the end of his life. Hattie Weste said she believed her mother put too much responsibility on his young shoulders. Gentry was blind in one eye from amblyopia, an hereditary condition in which a child is born with one eye either very nearsighted or farsighted, his sister Mella said it kept him from being drafted in the Great War, which angered him. Gentry was so eager to serve that eventually the commandant of Camp Wadsworth gave him the job of water boy which Mella said pleased him greatly.

Son Carlos died in 1926 from wounds suffered in France in The Great War in 1918. Carlos was a 1st Lieutenant and commanded a black fighting unit which was highly commended during the war for bravery. Carlos also graduated from Clemson Mechanical and Agricultural College, he was the editor for the Clemson school newspaper in his senior year & I'm recently told by a Clemson graduate doing a book on Clemson veterans that he organized the senior dance that year as well as being the captain of the basketball team. Carlos later graduated from Columbia Univ's law program in 1925 & passed the bar in NY, but he never practiced law, he joined McClellan's Dept. Store & managed their store in Iowa during the last year of his life until infection from his hip injury caused septicemia; he died in the New York Veteran's Hospital with his brother John by his side. John accompanied his body home to Spartanburg on the train, the newspaper article and his nephew Edwin said the funeral was so large that the police had to cordon off Main Street around the First Baptist Church for several blocks to accommodate all the attendees. Carlos is buried in the Oakwood family plot with his parents, he left no wife or children.

Daughters Hattie, Julia, Emily & Mella all became K-12 teachers in the Spartanburg school system; Hattie was first a private family governess, then taught grades 1-6 at Poplar Springs Elementary before she retired to raise 7 children; Julia became a Spartanburg public school history teacher & the family genealogist & raised 4 children; Emily taught 1st & 2nd grade & raised 3 children; Mella first taught physical education, and then switched to English, she retired from Cleveland Junior High School in 1969; her students remembered her as a tough and effective teacher; she never had any children but she took over the care of two nieces during the Depression and sent them to Converse College. All the children but Mella and Carlos married & all but Carlos, Mella & Joe had families. Mella told me once that nursing & teaching were considered the only 'respectable' jobs open to women at that time, she made it clear that she would've loved to have had a different career, particularly as a novelist.

Weste's youngest child Joe graduated from Clemson's world-famous agricultural program, then went to work for the Southern Railroad near his family home; he married twice but my mother said he had a physical defect and could not have children. Both his wives were named Lyda Mae. I remember Joe near the end of his life as a big jolly man with a very deep powerful voice that quite literally shook the house when he laughed, he reminded me of Santa. He died of a strange ailment that the many doctors he consulted could not diagnose, my mother said she believed he had lead poisoning from painting boxcars.

NOTE:

The marker on the Harris plot in West Oakwood cemetery is the main grist mill stone that came from Weste Harris's father David Golightly Harris's grist mill in Golightly, which was chronicled in his journal, transcribed & printed under the name "A Piedmont Farmer" by Wofford College professor Dr. Philip Racine. Weste's daughter Mella Harris had 3 grist mill stones, this one was the main stone. She also possessed the 2 other smaller stones from the grist mill which I remember sitting in her front yard near the sidewalk. Mella told me the local stonemasons refused at first to use the big stone because they believed it was too heavy to move. One finally agreed, but only if they could drill a large hole into the middle to hoist it up by crane. Mella thought this quite ironic since men had cut & moved this same stone several times in the 1800's-1900's with much more primitive technology. The monument is very distinctive & unique. The plot is in West Oakwood, next to the present-day Converse University playing field. Hattie Gentry Harris's parents are buried nearby, as are several of Weste & Hattie's children. Mella told me that West Oakwood was reserved for members of the elite of Spartanburg, she was quite proud her family was buried there.

--Jeni

Family Members

-

![]()

Amos Lyles "Liles" Harris

1887–1956

-

![]()

Landon Miles Harris

1888–1890

-

![]()

Frederick Gentry Harris

1890–1935

-

![]()

Julia Anna Harris Foster

1892–1978

-

![]()

Hattie Weste Harris Anderson

1894–1972

-

![]()

Dr John Weste Harris Jr

1895–1976

-

![]()

1LT Carlos Golightly "Kelly" Harris

1896–1926

-

Emily Jane Harris Patton

1898–1985

-

![]()

Joe Elmo Harris

1900–1964

-

![]()

Mary Ella "Mella" Harris

1902–1982

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement