James David Andrews had three military sons:

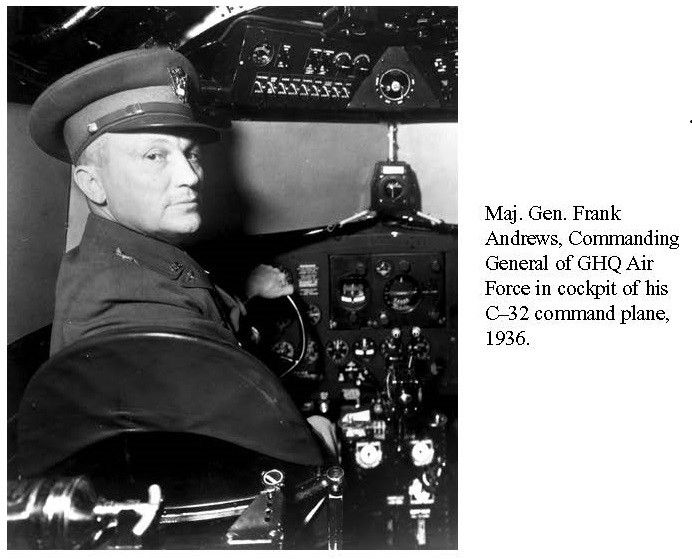

Lt. General Frank Maxwell Andrews after whom Andrews Airforce Base outside of Washington D.C. is named, William Valery Andrews and James David Andrews.

William Lafayette Andrews, Jr., who is related, played with General Andrews' niece, Louise Sikes, in Nashville, when they were children.

James David Andrews's great-uncles on his mother's side of the family were John Calvin Brown, Tennesse Governer and Confederate general and Neill Smith Brown (brothers who were both governors of Tennessee).

The Pulaski Citizen, November 11, 1880 edition

Mr. James D. Andrews, who, for a number of years, has been a most efficient member of the CITIZEN corps, left for Texas this morning on a prospecting tour. If he should succeed in making satisfactory arrangements there he will probably locate, but we hope he will find it to his interest to return, as Pulaski cannot afford to lose a young man of his high moral character and great social worth. Our sincere regard and best wishes will accompany him wherever he may go.

The Pulaski Citizen, December 2, 1880 edition

We are glad to hear that our Mr. Jas. D. Andrews stepped right into a good place upon a Dallas paper the next day after his arrival in Texas. Such men as he is are always in demand at the top.

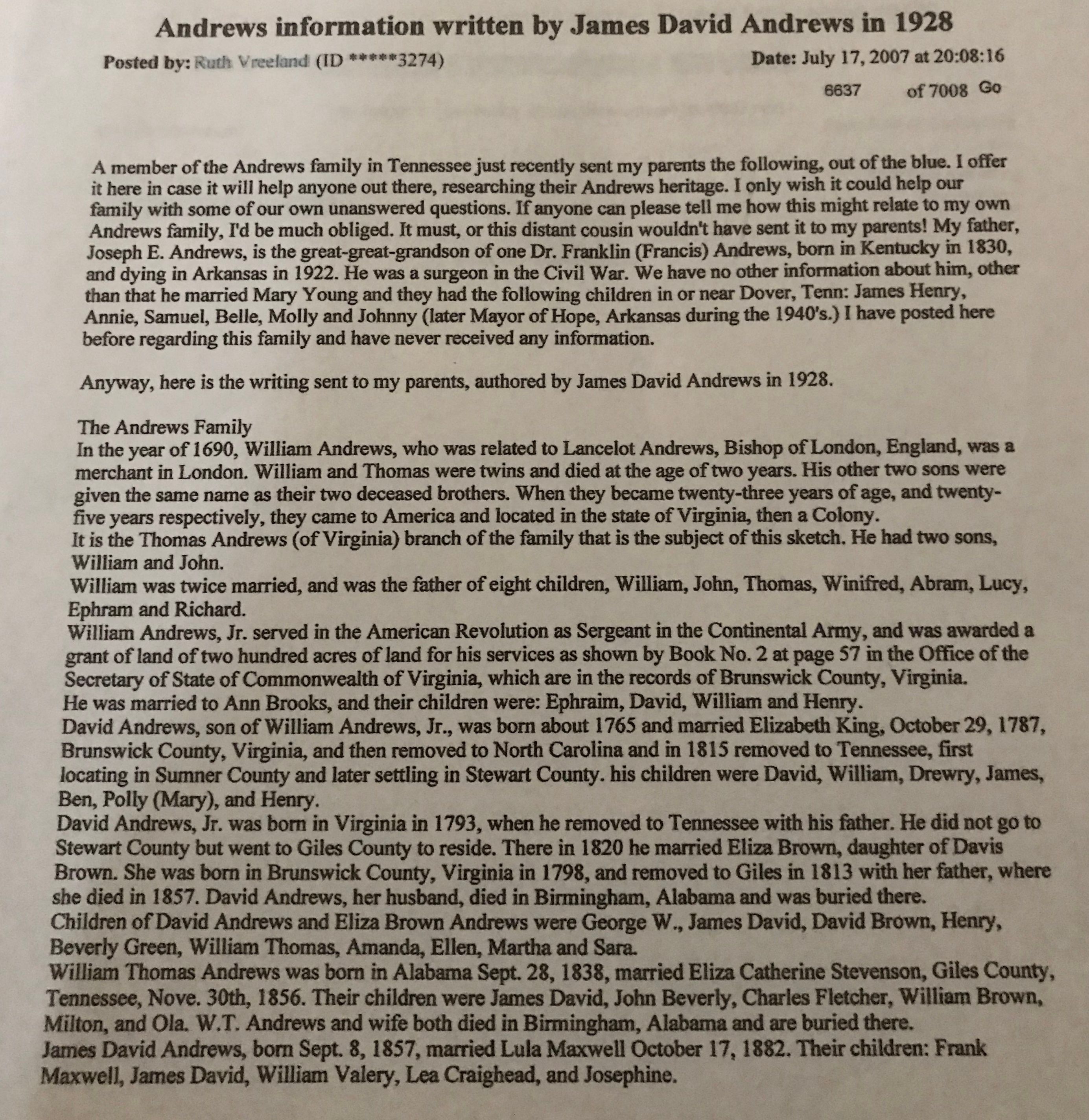

From Ruth Vreeland, Date: July 17, 2007 at 20:08:16:

A member of the Andrews family in Tennessee just recently sent my parents the following, out of the blue. I offer it here in case it will help anyone out there, researching their Andrews heritage. I only wish it could help our family with some of our own unanswered questions. If anyone can please tell me how this might relate to my own Andrews family, I'd be much obliged. It must, or this distant cousin wouldn't have sent it to my parents!

My father, Joseph E. Andrews, is the great-great-grandson of one Dr. Franklin (Francis) Andrews, born in Kentucky in 1830, and dying in Arkansas in 1922. He was a surgeon in the Civil War. We have no other information about him, other than that he married Mary Young and they had the following children in or near Dover, Tenn: James Henry, Annie, Samuel, Belle, Molly and Johnny (later Mayor of Hope, Arkansas during the 1940's.)

Morman Family Group Record

Husband; F M Andrews

Birth: 1833, Stewart, Tennessee

Marriage: 07 JUN 1858, Stewart, Tennessee

Wife; Mary Young

Birth: 1837, Stewart, Tennessee

Marriage: 07 JUN 1858, Stewart, Tennessee

Anyway, here is the writing sent to my parents, authored by James David Andrews in 1928.

From Ruth Vreeland, Date: July 17, 2007 at 20:08:16:

A member of the Andrews family in Tennessee just recently sent my parents the following, out of the blue. I offer it here in case it will help anyone out there, researching their Andrews heritage. I only wish it could help our family with some of our own unanswered questions. If anyone can please tell me how this might relate to my own Andrews family, I'd be much obliged. It must, or this distant cousin wouldn't have sent it to my parents! My father, Joseph E. Andrews, is the great-great-grandson of one Dr. Franklin (Francis) Andrews, born in Kentucky in 1830, and dying in Arkansas in 1922. He was a surgeon in the Civil War. We have no other information about him, other than that he married Mary Young and they had the following children in or near Dover, Tenn: James Henry, Annie, Samuel, Belle, Molly and Johnny (later Mayor of Hope, Arkansas during the 1940's.)

The Andrews Family

In the year of 1690, William Andrews, who was related to Lancelot Andrews, Bishop of London, England, was a merchant in London. William and Thomas were twins and died at the age of two years. His other two sons were given the same name as their two deceased brothers. When they became twenty-three years of age, and twenty-five years respectively, they came to America and located in the state of Virginia, then a Colony.

It is the Thomas Andrews (of Virginia) branch of the family that is the subject of this sketch. He had two sons, William and John. William was twice married, and was the father of eight children, William, John, Thomas, Winifred, Abram, Lucy, Ephram and Richard. William Andrews, Jr. served in the American Revolution as Sergeant in the Continental Army, and was awarded a grant of land of two hundred acres of land for his services as shown by Book No. 2 at page 57 in the Office of the Secretary of State of Commonwealth of Virginia, which are in the records of Brunswick County, Virginia. He was married to Ann Brooks, and their children were: Ephraim, David, William and Henry. David Andrews, son of William Andrews, Jr., was born about 1765 and married Elizabeth King, October 29, 1787, Brunswick County, Virginia, and then removed to North Carolina and in 1815 removed to Tennessee, first locating in Sumner County and later settling in Stewart County. his children were David, William, Drewry, James, Ben, Polly (Mary), and Henry.

David Andrews, Jr. was born in Virginia in 1793, when he removed to Tennessee with his father. He did not go to Stewart County but went to Giles County to reside. There in 1820 he married Eliza Brown, daughter of Davis Brown. She was born in Brunswick County, Virginia in 1798, and removed to Giles in 1813 with her father, where she died in 1857.

David Andrews, her husband, died in Birmingham, Alabama and was buried there. Children of David Andrews and Eliza Brown Andrews were George W., James David, David Brown, Henry, Beverly Green, William Thomas, Amanda, Ellen, Martha and Sara.

William Thomas Andrews was born in Alabama Sept. 28, 1838, married Eliza Catherine Stevenson, Giles County, Tennessee, Nove. 30th, 1856. Their children were James David, John Beverly, Charles Fletcher, William Brown, Milton, and Ola. W.T. Andrews and wife both died in Birmingham, Alabama and are buried there.

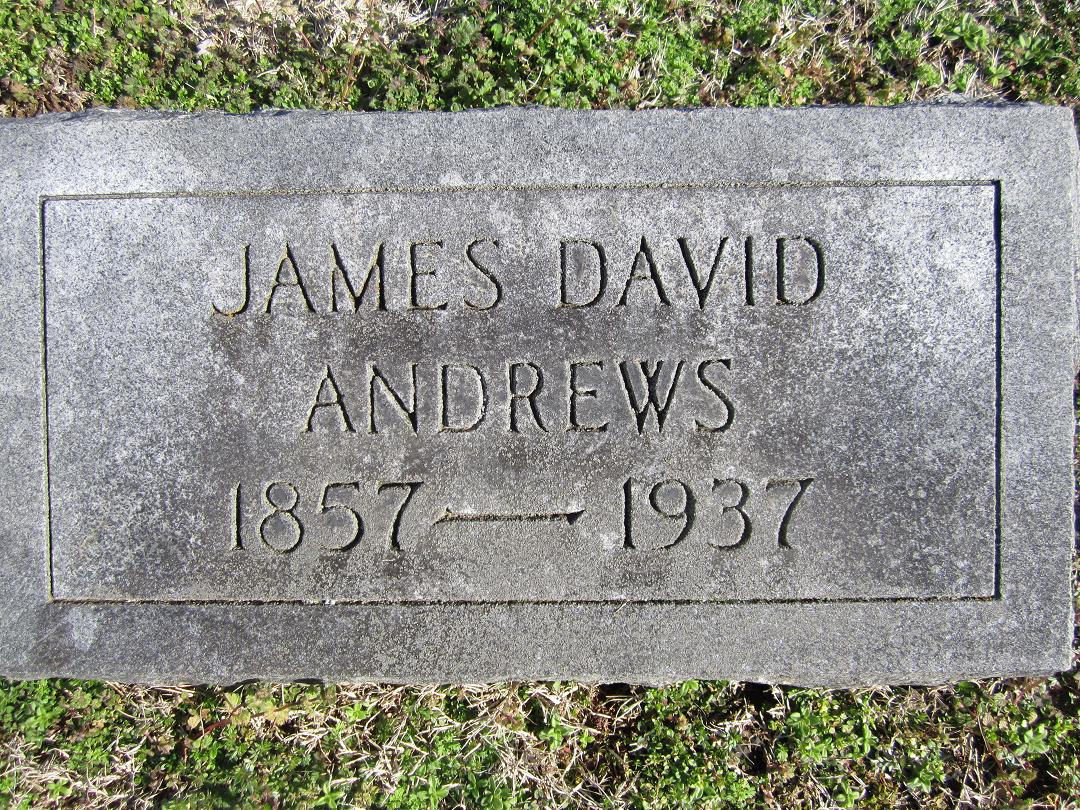

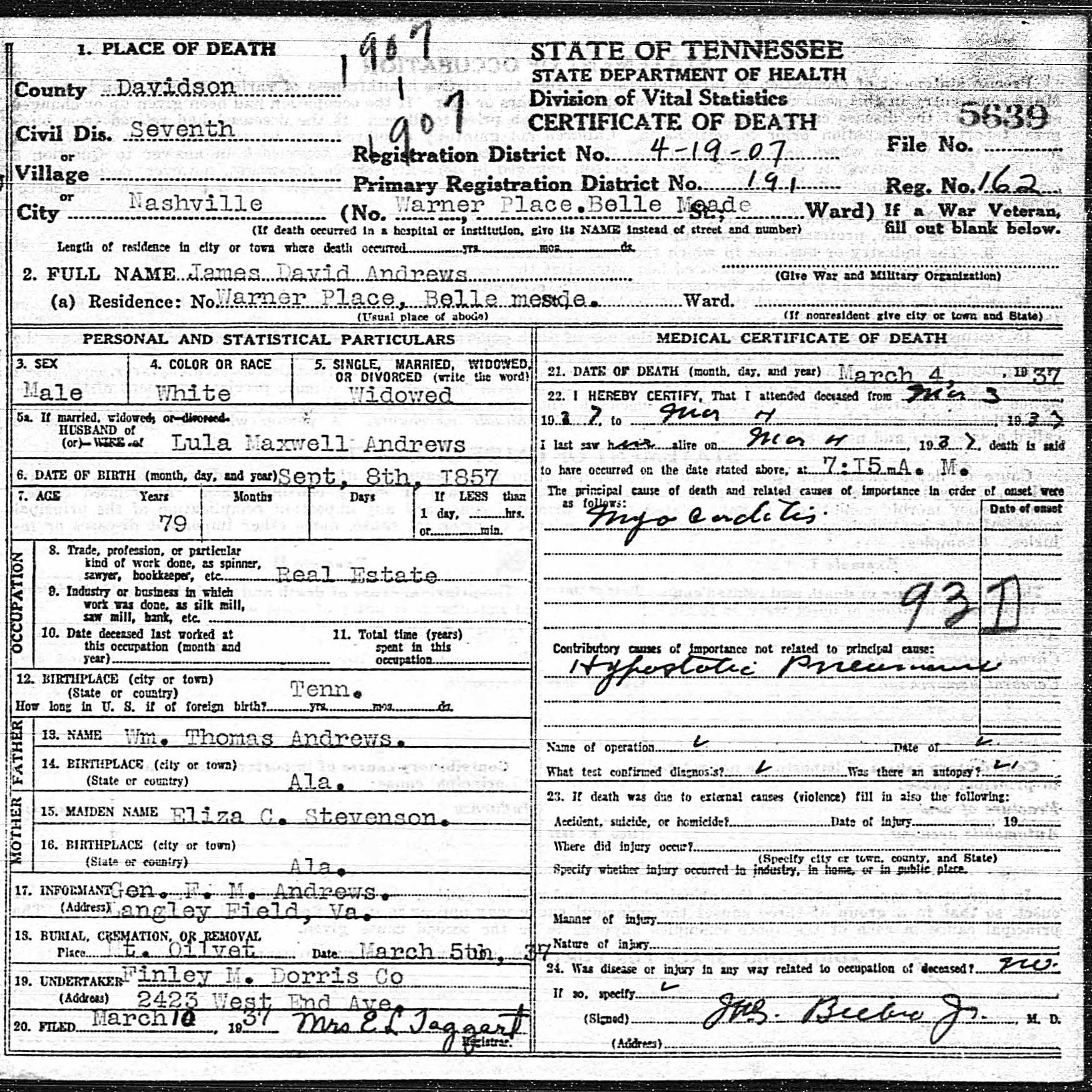

James David Andrews, born Sept. 8, 1857, married Lula Maxwell October 17, 1882. Their children: Frank Maxwell, James David, William Valery, Lea Craighead, and Josephine.

Ben Andrews, son of David Andrews, Sr. was married in Stewart County, Tennessee and resided there until his death. His children were Jane, Sara and William. Henry Andrews, son of David Andrews, Sr. married Rebecca Sexton in Stewart County and settled on a farm near Dover; their children were Emma, Mary, Pinkney, Eliza, Joiner, Missouri, and Marion R.

Marion R. Andrews married Emma McGee. He and his sister Eliza Cole now reside on the farm which their father settled and died.

C. Pinkney (Pink) Andrews, born in Stewart County, Oct. 8, 1836, married Maria Elizabeth Laurie, Jan. 2, 1873, at Paducah, Ky. Lived in Bells, Tennessee.

The authority for the compilation of the above data was derived from sundry sources, with satisfactory warrant for its correctness.

James David Andrews -- Nashville, Tennessee, Sept. 8, 1928

_____________

And I've been studying this letter written by James David Andrews again today... I copied the entire letter, so unfortunately, there is no further information. However, my Grandpa Andrews' cousin (J.D. Garland) who provided this letter to my parents 5 yrs. ago, also gave them 11 other pages, stapled together, which are copies out of a book titled "The Heritage of Montgomery Co., N.C., 1981." (I'd sure love to have the entire book someday!). J.D. Garland is married to one of my Dad's distant Andrews cousins. I'm not sure where J.D. lives, but will try to get that information from my parents soon. They met him at an Andrews family reunion in Paris Tennessee over Memorial Day weekend. I'm not sure where the information came from originally, other than the date at the bottom which is Sept. 8, 1928 -- in this typed letter from James David Andrews. How J.D. and his wife got it, I don't know -- and I also don't know how it possibly relates to our branch of the family, since there are so many unknowns on that part of my family tree. I can't seem to find anyone with information about my great-great-great grandfather, Franklin Andrews, who was a Dr. in the Civil War.

I was able to piece together a BIT more information about my own Andrews family, from one of the articles. I understand now that the typed letter from James David Andrews IS about my Andrews family, so that's very exciting for me. I believe that the two sons who came to America in the early to mid 1700's (William and Thomas) landed in the area of Brunswick, VA, as William's oldest child, William Jr. fought in the Revolutionary War as Sergeant in the Continental Army "and was awarded a grant of land of two-hundred acres of land for his services as shown by Book No. 2 at page 57 in the office of the Secretary of State of the Commonwealth of Virginia, which are in the records of Brunswick County, Virginia." This was James David Andrews' ancestor. I believe Williams's second oldest son John was MY John Andrews of Brunswick, VA, who later moved to Stewart Co., Tenn., as another article speaks more about this John's family, and it ties to mine very well.

Yes, I do believe this letter IS stating that William and Thomas Andrews were the sons of William Andrews, the London merchant in 1690. Is it possible that James David Andrews may have written his letter in a less-than-stellar state of mind, even though he would have only been about 61? Could he have had dates wrong? And no, the William and Thomas who came to America were not twins ... the twins had died at age two, and the younger brothers who were not twins were named for them. If they did come to America at ages 23 and 25, it would have been in about 1715 or 1720, if William the merchant was living in London in 1690 with small children ... right?? I have tried to tie THIS William and Thomas to the "Thomas Andrews" original Virginia settler, from whom all the Southern Andrews say they are descended, but I can't find that connection. Am I missing something? According to James David Andrews' letter, this appears to be a different family ... but then, I just don't know! I have a lot of research to do on this family. Thank you!

The 11 pages stapled together which appear to have copies of articles on them, with photos that are so washed out you can't make them out anymore. I believe all or most of the material comes from a book titled: "The Heritage of Montgomery Co., N.C., 1981" IBSN 0-89459-153-3. The articles on these pages are as follows (spellings left intact):

1. Mrs. Ellen Andrews [about the life of "Granny Andrews" married to Eli Franklin Andrews in 1865]

2. "The Andrews Family" [about the roots of the pioneer family who settled Montgomery Co., N.C. in the 18th century -- and also about the family of John Andrews from Brunswick Co., Virginia -- whose father-in-law was John Scarborough, Sr.]

3. an obituary for George Washington Andrews dated 1934

4. "Mrs. Ida Lee Andrews" [wife of Dr. Vernon L. Andrews, Sr. -- of Mt. Gilead]

5. "Dr. Vernon Liles Andrews, Sr." [an article about him written by Evelyn Andrews Hughes]

6. "The Descendants of Dr. Vernon Liles Andrews, Sr." again by Evelyn Andrews Hughes]

7. "The Robert Edgar Andrews Family" -- eldest of 10 children of George Washington and Martha Scarborough Andrews [an article by Marc Andrews]

8. "Thomas B. and Lena Harris Andrews" -- son of George W. and Martha Scarboro Andrews [an article by Lena H. Andrews]

9. "The Scarborough Family" -- descended from James Allen Scarborough, King of Wales in the mid-1700's [article by Iris Scarborough and Leah S. Barton]

10. "The Scarborough Family" [article by Margaret Scarborough Dickinson]

11. "The Scarborough Family Genealogy" and "Oscar Robert Scarborough Family."

Oh, and I too would LOVE to know more about Launcelot Andrews, Bishop of London!

Ruth Vreeland

__________________

LANCELOT ANDREWS

He was born at London, in 1565. He was trained chiefly at Merchant Taylor's school, in his native city, till he was appointed to one of the first Greek Scholarships of Pembroke Hall, in the University of Cambridge. Once a year, at Easter, he used to pass a month with his parents. During this vacation, he would find a master, from whom he learned some language to which he was before a stranger. In this way after a few years, he acquired most of the modern languages of Europe. At the University, he gave himself chiefly to the Oriental tongues and to divinity. When he became candidate for a fellowship, there was but one vacancy; and he had a powerful competitor in Dr. Dove, who was afterwards Bishop of Peterborough. After long and severe examination, the matter was decided in favor of Andrews. But Dove, though vanquished, proved himself in this trial so fine a scholar, that the College, unwilling to lose him, appointed him as a sort of supernumerary Fellow. Andrews also received a complimentary appointment as Fellow of Jesus College, in the University of Oxford. In his own College, he was made a catechist; that is to say, a lecturer in divinity.

His conspicuous talents soon gained him powerful patrons. Henry, Earl of Huntingdon, took him into the North of England; where he was the means of converting many papists by his preaching and disputations. He was also warmly befriended by Sir Francis Walsingham, Secretary of State to Queen Elizabeth. He was made parson of Alton, in Hampshire; and then Vicar of St. Giles, in London. He was afterwards made Prebendary and Canon Residentiary of St. Paul's, and also of the Collegiate Church of Southwark. He lectured on divinity at St. Paul's three times each week. On the death of Dr. Fulke, in 1589, Dr. Andrews, though so young, was chosen Master of Pembroke Hall, where he had received his education. While at the head of this College, he was one of its principal benefactors. It was rather poor at that time, but by his efforts its endowments were much increased; and at his death, many years later, he bequeathed to it, besides some plate, three hundred folio volumes, and a thousand pounds to found two fellowships.

He gave up his Mastership to become chaplain in Queen Elizabeth, who delighted in his preaching, and made him Prebendary of Westminster, afterwards Dean of that famous church. In the matter of Church dignities and preferments, he was highly favored. It was while he held the office of Dean of Westminster, that Dr. Andrews was made director, or president, of the first company of Translators, composed of ten members, who held their meetings at Westminster. The portion assigned to them was the five books of Moses, and the historical books to the end of the Second Book of Kings. Perhaps no part of the work is better executed than this.

With King James, Dr. Andrews stood in still higher favor than he had done with Elizabeth. "The Canterbury is the higher rack, but Winchester is the better manger." At the time of this last preferment Dr. Andrews was appointed Dean of the King's chapel; and these stations he retained till his death.

In the high offices Bishop Andrews filled, he conducted himself with great ability and integrity. The crack-brained king, who scarce knew how to restrain his profanity and levity under the most serious circumstances, was overawed by the gravity of this prelate, and desisted from mirth and frivolity in his presence. And yet the good bishop knew how to be facetious on occasion. Edmund Wailer, the poet, tells of being once at court, and overhearing a conversation held by the king with Bishop Andrews, and Bishop Neile, of Durham. The monarch, who was always a jealous stickler for his prerogatives, and something more, was in those days trying to raise a revenue without parliamentary authority. In these measures, so clearly unconstitutional, he was opposed by Bishop Andrews with dignity and decision. Wailer says, the king asked this brace of bishops," My lords, cannot I take my subject's money when I want it, without all this formality in parliament?" The Bishop of Durham, one of the meanest of sycophants to his prince, and a harsh and haughty oppressor of his puritan clergy, made ready answer," God forbid, Sir, but you should; you are the breath of our nostrils!" Upon this the king looked at the Bishop of Winchester; "Well my lord, what say you?" Dr. Andrews replied evasively, "Sir, I have no skill to judge of parliamentary matters." But the king persisted, "No put offs, my lord, answer me presently? "Then, Sir," said the shrewd Bishop, "I think it lawful for you to take my brother Neile's money, for he offers it." Even the petulant king was hugely pleased with this piece of pleasantry, which gave great amusement to his cringing courtiers.

"For the benefit of the afflicted," as the advertisements have it, we give a little incident which may afford a useful hint to some that need it. While Dr. Andrews was one of the divines at Cambridge, he was applied to by a worthy alderman of that drowsy city, who was beset by the sorry habit of sleeping under the afternoon sermon; and who, to his great mortification, had been publicly rebuked by the minister of the parish. As snuff had not then came into vogue, Dr. Andrews did not advise, as some matter-of-fact persons have done in such cases to titillate the "sneezer" with a rousing pinch. He seems to have been of the opinion of the famous Dr. Romaine, who once told his full-fed congregation in London, that it was hard work to preach to two pounds of beef and a pot of porter. So Dr. Andrews advised his civic friend to help his wakefulness by dining very sparingly. The advice was followed; but without avail. Again the rotund dignitary slumbered and slept in his pew; and again was he roused by the harsh rebukes of the irritated preacher. With tears in those too sleepy eyes of his, the mortified alderman repaired to Dr. Andrews, begging for further counsel. The considerate divine, pitying his infirmity, recommended to him to dine as usual, and then to take his nap before repairing to his pew. This plan was adopted; and to the next discourse, which was a violent invective prepared for the very purpose of castigating the alderman's somnolent habit, he listened with unwinking eyes, and his uncommon vigilance gave quite a ridiculous air to the whole business. The unhappy parson was nearly as much vexed at his huge-waisted parishioner's unwonted wakeful-ness, as before at his unseemly dozing.

Bishop Andrews continued in high esteem with Charles I; and that most culpable of monarchs, whose only redeeming quality was the strength and tenderness of his domestic affections, in his dying advice to his children, advised them to study the writings of three divines, of whom our Translator was one.

Lancelot Andrews died at Winchester House, in Southwark, London, September 25th, 1626, aged sixty-one years. He was buried in the Church of St. Saviour, where a fair monument marks the spot. Having never married, he bequeathed his property to benevolent uses. John Milton, then but a youth, wrote a glowing Latin elegy on his death.

As a preacher, Bishop Andrews was right famous in his day. He was called the "star of preachers." Thomas Fuller says that he was "an inimitable preacher in his way; and such plagiarists as have stolen his sermons could never steal his preaching, and could make nothing of that, whereof he made all things as he desired." Pious and pleasant Bishop Fei-ton, his contemporary and colleague, endeavored in vain in his sermons to assimilate to his style, and therefore said merrily of himself, "I had almost marred my own natural trot by endeavoring to imitate his artificial amble." Let this be a warning to all who would fain play the monkey, and especially to such as would ape the eccentricities of genius. Nor is it desirable that Bishop Andrews' style should be imitated even successfully; for it abounds in quips, quirks, and puns, according to the false taste of his time. Few writers are" so happy as to treat on matters which must always interest, and to do it in a manner which shall for ever please." To build up a solid literary reputation, taste and judgment in composition are as necessary as learning and strength of thought. The once admired folios of Bishop Andrews have long been doomed to the dusty dignity of the lower shelf in the library.

Many hours he spent each day in private and family devotions; and there were some who used to desire that "they might end their days in Bishop Andrews's chapel." He was one in whom was proved the truth of Luther's saying, that "to have prayed well, is to have studied well." His manual for his private devotions, prepared by himself, is wholly in the Greek language. It has been translated and printed. This praying prelate also abounded in alms-giving; usually sending his benefactions in private, as from a friend who chose to remain unknown. He was exceedingly liberal in his gifts to poor and deserving scholars. His own instructors he held in the highest reverence. His old schoolmaster Mulcaster always sat at the upper end of the Episcopal table; and when the venerable pedagogue was dead, his portrait was placed over the bishop's study door. These were just tokens of respect "For if the scholar to such height did reach, Then what was he who did that scholar teach?"

This worthy diocesan was much "given to hospitality," and especially to literary strangers. So bountiful was his cheer, that it used to be said, "My lord of Winchester keeps Christmas all the year round." He once spent three thousand pounds in three days, though "in this we praise him not," in entertaining King James at Farnham Castle. His society was as much sought, however, for the charm of his rich and instructive conversation, as for his liberal housekeeping and his exalted stations.

But we are chiefly concerned to know what were his qualifications as a Translator of the Bible. He ever bore the character of "a right godly man," and "a prodigious student." One competent judge speaks of him as "that great gulf of learning!" It was also said, that "the world wanted learning to know how learned this man was." And a brave old chronicler remarks, that, such was his skill in all languages, especially the Oriental, that, had he been present at the confusion of tongues at Babel, he might have served as Interpreter-General! In his funeral sermon by Dr. Buckeridge, Bishop of Rochester, it is said that Dr. Andrews was conversant with fifteen languages.

____________

Chronology

1857 Sept. - James D. Andrews born in Tennessee

1883 circa - James D. Andrews marries Lula Adaline Maxwell

1883-1901 - James D. Andrews works as business manager at the Nashville Banner newspaper

1884 Feb. 3 - Son Frank Maxwell Andrews born

1887 Dec. - Son James D. Andrews, Jr. born

1888 Aug. - Son William Valery Andrews born

1892 July - Daughter Josephine Andrews born

1900 - James D. Andrews listed as real estate agent. Unknown when he began in this occupation; he continues this work until his death

1918 - All three sons serve overseas during World War I

1921 circa - Blackwood Field opened near the Hermitage as a base for the 105th Observation Squadron. Its creation made possible in part by contributions of Nashville businessmen, especially members of the Commercial Club, including a generous donation of $1,000 from H.O. Blackwood, for which it is named.

1924 July 29 - First airmail flight from Nashville departs Blackwood Field.

1927 - Construction begins on McConnell Field, first municipal airport in city. Named for Lt. Brower McConnell, a Tennessee National Guard pilot killed in a crash in 1927.

1927 Nov. 29 - 105th Observation Squadron begins move from Blackwood Field to McConnell Field

1928 - Blackwood Field closed

1928 Dec. 1 - Air mail via Contract Air Mail (C.A.M.) Route 30, running from Atlanta to Chicago through Nashville's McConnell Field, begins.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 2

1929 June 5 - Construction begins on Sky Harbor airport, near Murfreesboro

1929 Sept. - Mayor Hilary Howse forms committee to assist in location and development of a class A-1 airport for Nashville. Committee members: E. A. Lindsay, chairman of the Chamber of Commerce aeronautics committee; James E. Caldwell; James A. Cayce, president of the Chamber of Commerce; James I. Finney; James G.Stahlman; Albert E. Hill.

1929 Oct. 14 - Dedication of Sky Harbor. It will become Nashville's main airport, despite the fact that it is located near Murfreesboro.

1930 Nov. 25 - 105th Observation Squadron moved to Armstrong Field in Memphis

1931 Jan. 30 - Granville Rucker and Ed Houston die in plane crash in Richland neighborhood, near McConnell Field

1931 Apr. 17 - 105th Observation Squadron moved from Memphis to Sky Harbor near Murfreesboro

1932 Feb. 24 - Bomber badly wrecked at McConnell; pilot did not think Nashville's airport would be in another county (Sky Harbor)

1932 Apr. 19 - Lula Maxwell Andrews dies.

1934 - Eastern Airlines begins operating out of Sky Harbor

1934 Dec. 19 - Strong winds damage planes, blow down tents used as hangars at McConnell Field

1935 - Members of city airport committee include: Will T. Cheek, chair; R.B. Beal, secretary; Ed Potter, John Sloan, Col. Herbert Fox, all representing Chamber of Commerce; Gen. J.H. Ballew, representing the State; James G. Stahlman, Nashville Banner; Lt J.Pardue, The Tennessean; T.B. Faucett, Nashville Labor Advocate; Dr. J.W. Bauman, Luther Luton, Mayor Howse, all representing the City; Dr. W.D. Haggard and W.O. Rhodes (affiliation unidentified)

1935 Nov. 5 - Nashville City Council passes $100,000 bond issue to construct new airport

1936 June 24 - An American Airlines DC-2 is first airplane to land at new Nashville airport, still under construction off of Murfreesboro Rd.

1936 Nov. 1 - Dedication ceremonies for Nashville Municipal Airport

1937 - State of Tennessee establishes Bureau of Aeronautics within the Department of Highways

1937 - McConnell Field closes

1937 - Commercial air traffic now routed through Nashville Municipal Airport instead of Sky Harbor

1937 Mar. 4 - James D. Andrews dies.

1937 June 12-13 - Official opening day celebration of Nashville Municipal Airport; the DC-3 American Airlines "Flagship Tennessee" is christened; many notable aviators attend

1938 Jan. 1 - 105th Observation Squadron moves from Sky Harbor to Nashville Municipal Airport (Berry Field)

--------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 3

Biographical/Historical Sketch

James D. Andrews was born in September 1857 in Tennessee. He married Lula Adaline Maxwell around 1883. Together they had a daughter, Josephine (the future Mrs. Gillespie Sykes); and three sons, all of whom served in the military: Frank Maxwell Andrews; James D. Andrews, Jr.; and William Valery Andrews. James D. Andrews, Sr. was business manager of the Nashville Banner newspaper from 1883 to 1901 and was a real estate agent in Nashville, Tenn. in the early 1900s. He was a vocal advocate for aviation in the city, so much so that some citizens even proposed that the new Nashville airport, opened in 1936, be named in his honor. He represented at least four property owners (William O. Harris; Rychen Brothers dairy; Flora Hammer Bean; and A. A. Buckingham) in the sale of land to the City for the future airport. James D. Andrews died on March 4,1937 at his home in Warner Place, in Belle Meade, Tenn., and was buried at Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Nashville, Tenn.

Scope and Contents of the Collection

Manuscripts, primarily consisting of original and copy letters, and news clippings relating to activities of Nashville real estate agent James D. Andrews and the subject of aviation in Nashville during the 1920s and 1930s, especially the creation of Nashville Municipal Airport in 1936. Manuscripts provide strong documentation of Andrews' personal involvement and activities, while news clippings provide a broader view of aviation in Nashville.

Manuscripts cover the time period of 1912-1943 and consist primarily of original and carbon copies of letters written to or by James D. Andrews, and also include sketch maps of property under consideration as potential sites for the new airport, layouts and diagrams of actual or hypothetical airports, and occasional brochures or other documents relating to aviation in Nashville, Tennessee, and the greater Southeast. Four local airfields figure prominently in these materials: Blackwell Field (Hermitage, Tenn.), McConnell Field (Nashville, Tenn.), Sky Harbor (Murfreesboro, Tenn.) and Nashville Municipal Airport, also known as Berry Field.

Subjects include: air mail routes and services; military aviation, especially the 105th Observation Squadron, based in Nashville and moved to both Memphis and Sky Harbor; inadequacies and safety risks of older fields if they continue to be used; specifications necessary for a new field; growth of the aviation industry in general, throughout the Southeast, and in Nashville; increasing demand for passenger service; aviation as a component of industrial growth and commercial development; support from the business community and Chamber of Commerce for a new airport; civic pride and boosterism about Nashville and the desire for a new airport, presenting Nashville as a "modern" city and in competition with other Southern cities, especially Memphis and Atlanta; and weather problems associated with Nashville which make flying difficult, including frequent fogs and soot from the city. Not surprisingly, due to Andrews's work as a real

--------------------------------------

Page 4

estate agent, much of the collection concerns land and property owners in areas under consideration for the new airfield, with a number of sketch maps, descriptions of property, property values, correspondence to and from land owners, and related matters. A number of different areas were considered as a possible location for the field, including property belonging to the Thompson family along Franklin Road, reopening of Blackwood Field, land in the Bordeaux area, and finally, the Harris farm site and adjoining lands on Murfreesboro Road (the Dixie Highway) – the latter being the site that eventually was chosen. As movement was being made on constructing a new airport in the mid-1930s, additional materials document the involvement of state, city, and national governments in the building of the new airport, especially numerous New Deal agencies of the Federal government, including the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Civil Works Administration (CWA), as well as other agencies, such as the Department of Commerce, which regulated airports. Other topics include construction methods, materials, and costs; funding sources; debate about the selection of a site for the new airport, and even skepticism that a new airport was needed at all. Other government-related topics include actions taken by the City and mayor in support of or opposition to anew airport; the suggestion to use the Park Commissioners as a model for development of an Airport Commission for the City; and activities of the Airport Commission. Other topics include visiting dignitaries, such as notable aviators and military and commercial aviation officials; and the proposed reuse of McConnell Field.

Some letters debate and provide commentary about the affect of airplanes upon the residents of mental asylums when asylums are in close proximity to an airport, of special concern since Central State Psychiatric Hospital was located near the Harris farm site, the eventual location of the new airport. Manuscripts also include some comments from James D. Andrews's son, Gen. Frank Maxwell Andrews of the U.S. Army Air Forces, who wrote in support of his father's claims and provided specifications, referrals, guidance and suggestions to his father in his advocacy efforts.

Specific incidents which are documented include: the death of Ed Houston and Granville Rucker in a plane crash in the Richland neighborhood of Nashville, near McConnell Field on Jan. 30, 1931; the proposed amendment of the City Charter in 1931 to create an Airport Commission; and the dedication (Nov. 1, 1936) and opening day (June 12-13,1937) ceremonies at Nashville Municipal Airport, also known as Berry Field, named in honor of Col. Harry S. Berry, State WPA Administrator. An early (circa 1915) brochure written by the future father-in-law of Frank M. Andrews, Lt. Col. Henry T. Allen, entitled "The Dixie Highway as a Military Asset" (Folder 1); a program from the opening of the Birmingham, Ala. airport in 1931 (Folder 75); and an article by Herbert Fox entitled, "Tennessee's Aviation Future" providing an overview of various airfields in the state (Folder 36), are also included in the manuscripts subseries. Additional topics which are incidental to the above and which appear to have no bearing on Andrews's airport advocacy include a few papers related to his work as a real estate agent and his religious beliefs. His occasional habit of using stray bits of paper as notepaper results in the documentation of several small businesses and other minutiae relating to Nashville in the 1920s and 1930s.

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 5

News clippings, covering the approximate time period of 1927-1937, essentially document most of the same subjects as the manuscripts, described above, although there is the notable contrast of the manuscripts documenting Andrews's personal involvement in aviation issues, while the clippings enable a broader view of the same subject, especially the community's response to the issue. Clippings also include photographs printed in the newspaper, editorials, letters to the editor, and editorial cartoons, providing visual information as well as a diversity of opinion. The majority of the clippings are undated.

Subjects contained in the clippings, in addition to those described above in the manuscripts subseries, include: the opening of Sky Harbor, attended by many well-known aviators; various government actions related to aviation and construction of a new airport, some favorable, some opposed; the 105th Observation Squadron; technical matters related to a new airfield, including proximity of electrical power, roadways, post office, and other details; opposition of the Ladies' Hermitage Association to the reopening of Blackwood Field; visits of Gen. Frank Maxwell Andrews to Nashville and vicinity; commercial airlines' involvement and advocacy for new airport; the National Air Tour's stop at Sky Harbor; Federal involvement in aviation and creation of a new airfield; technical matters relating to aviation such as night flying, radio navigation, and the increasing size, speed, and power of airplanes; James D. Andrews's letters to the editor and other actions he took in his support for aviation in Nashville; and extensive coverage, including photographs printed in the paper, about the dedication of Nashville Municipal Airport on Nov. 1 and 2, 1936.

Clippings also include a short series of articles entitled, "Learning to Fly in Nashville," a column written in 1929 by a Tennessean newspaper reporter who learns to fly; photographs and biographical information about the three sons of James D. Andrews and their military careers; the first airmail flight from Nashville to Old Hickory; and an "Air Circus" held at McConnell Field, featuring the "boy parachutist" Hugh Thomasson.

Individuals featured prominently in both the manuscripts and clippings subseries as authors, recipients, or subjects include: James D. Andrews; his son, Gen. Frank Maxwell Andrews; Nashville Mayor Hilary Howse; James A. Cayce; Capt. Herbert Fox; James G. Stahlman; Will T. Cheek who served on the Airport Commission; Gov. Hill McAlister; Capt. Charles G. Pearcy; and Granville Rucker and Ed Houston, both of whom died in a plane crash near McConnell Field in 1931. Other persons include editorial cartoonists; various government officials and a number of representatives from commercial airlines, especially Interstate Airlines and American Airways. Many other individuals appear in the collection, but are not featured as prominently as those mentioned above.

A wide variety of other subjects and persons are represented in the James D. Andrews Series of the collection. Researchers are advised to consult the two extensively detailed sections of this finding aid: the Contents Index and the Detailed Folder Listing, for more information.

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 6

Organization/Arrangement of Materials

The collection is organized into the following series:

I. James D. Andrews Series

II. Frank Maxwell Andrews Series

III. Miscellaneous Nashville subjects

Series I is divided further into the following subseries by format:

A. Manuscripts, 1912-1943 (arranged chronologically)

B. News clippings, 1927-1937 (no arrangement scheme)

Personal Names:

Andrews, Frank Maxwell, 1884-1943 -- Correspondence

Andrews, James David, 1857-1937 -- Correspondence

Andrews, James David, b. 1887

Andrews, William Valery, b.1888

Cheek, Will T., 1886-1958

Fox, Herbert F. (Herbert Franklin), 1896-1952

Houston, Ed (Edward C.), d. 1931

Howse, Hilary E. (Hilary Ewing), 1866-1938

McAlister, Hill, 1875-1959

Rucker, Granville, d.1931

Added Authors: Allen, Henry T. (Henry Tureman), 1859-1930

Associated and Related Material

A ten-page letter from James D. Andrews to Hartwell Brown Grubbs, dated Feb. 26,1932 is held by the Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville, Tenn.

Most materials created or collected by James D. Andrews, although a few items are dated after his death.

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 9

In addition, their holdings also include two manuscript collections relating to the Andrews family: the Frank Maxwell Andrews Papers and the William Valery Andrews Papers.

Detailed Description of the Collection

Series I. James D. Andrews Series, 1912-1943, 1 cu. ft.

Sub-series A. James D. Andrews Manuscripts, 1912-1943, .5 cu. ft.

Series Abstract/Description: Correspondence and other manuscript materials documenting James D. Andrews's efforts as an advocate for aviation in Nashville, Tenn. and in particular, his efforts to get a new modern airport built for the city.

Arrangement: Rough chronological order – many items undated or of uncertain date

Container List: Folders 1-52, 75

Sub-series B. James D. Andrews Clippings, 1927-1937, .46 cu. ft.

Series Abstract/Description: Newspaper clippings, mostly from the Nashville Banner, Tennesseean, and Nashville American newspapers concerning aviation in Nashville, including air mail, military aviation and the 105th Observation Squadron, and the effort to build a new airport in Nashville, which would become Nashville Municipal Airport, also known as Berry Field. Contains numerous clippings about two of Nashville's airfields: McConnell Field and Blackwood Field, as well as Sky Harbor near Murfreesboro.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 38

VI. Photographs

All photographs appear in newspaper clippings, unless otherwise noted

Folder Description

53 Frank Maxwell Andrews with granddaughter, Allen Reavis Williams, on their shared birthday

James Andrews Sr.; James Andrews Jr.; and Frank Maxwell Andrews

aerial photograph of Harris farm site, prior to construction of airport

54 aerial photograph of crowd attending opening ceremonies at Municipal Airport

Frank Maxwell Andrews in full flight gear, shaking hands with his father, James D. Andrews Sr., and Ellen Sikes [Sykes]

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 39

81 James D. Andrews and sons

85 Maj. Frank Maxwell Andrews, Capt. James D. Andrews, 1st Lt. William Valery Andrews and other officers from Nashville who are in the Army, 1921

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Page 40

Handwritten annotation indicates Lt. Andrews was a pilot.

Medals of Capt. James D. Andrews, Jr., 1926

Nashville aviators including Johnny MacKenzie in his last photobefore his death from setting off fireworks

VII. Editorial cartoons

Folder Description

----------------------------------------------------------------

Page 41

VIII. Miscellaneous items on unrelated subjects

James D. Andrews often used whatever paper was at hand to write notes or drafts, and frequently wrote on the backs of advertisements, letters, and other documents. Many of the items described below are incidental to the contents of the James D. Andrews Series, but nevertheless may be of interest to the local history researcher.

Folder Description

1 brochure: "Dixie Hwy. as Military Asset"

3 letter from unidentified church regarding fundraising, Synod of Tennessee will meet in Nashville in Oct. Signed by ___ Hearn,1926

8 form letter from Joe P. McCord, Davidson County tax assessor,1924

10 Caldwell & Co. information sheet for municipal bonds for CarterCo., 5% school bonds, 1928

12 advertisement for opening day of Hermitage Laundry on West End Ave., Feb. 19, 1927

--------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 42

90 Advertisement from Florsheim Shoe Shop, made to resemble newspaper, seeking J.D. Andrews as "missing customer" c. 1935

Detailed Folder Listing

Abbreviations: FMA = Frank Maxwell Andrews

JDA = James D. Andrews

Subseries A – Manuscripts

Folder Summary of contents

1 weather & threshing in Ariz.; brochure: "Dixie Hwy. as Military Asset" by Lt. Col. Henry T. Allen; handwritten list of medals and awards for James D. Andrews, Jr.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 43

8 notes of values and acreage of lands; description of Smith tract and value; comments from Maj. (F.M.) Andrews; air mail;

1929: smoke and fog problems; Sweeney farm; McConnell Field; State Senate Bill 327 granting Nashville the right of eminent domain to condemn and acquire land for airport; bonds; specifications for a safe field; summary of visits and reports by Federal and state officials; advocacy letters to newspapers by JDA; plan for growth of airport and size of planes; *see also Box 3 Folder 75. 1927: Costs of purchasing Kennon and McEwen land; JDA discourages site of Sloan land due to elevations and underlying rock; comparison of dirt and fill and expenses of Sloan and Berry lands, description of lands

13 Harris farm assets; dangers of McConnell Field; weather conditions, water and electric provisions at Harris site; letter from JDA to unidentified person, inquiring about specifics of an airfield being used by the correspondent

14 note about timber value on Harris farm and cost of removal; JDA inquires of Howse if Howse is open to suggestions; note by JDA on letter from Phillips stating that Phillips' report does not recommend McConnell Field

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 44

15 JDA reports on meeting with Dr. Core, superintendent of Davidson County Insane Asylum, Core reported inmates of asylum not disturbed by planes landing nearby in open field or flying over; FMA provides general social news and recommends Harris farm site, states Bolling Field and Naval Air Station are near an asylum; Bogle states the Committee did not investigate or inquire about Insane Asylum, Bogle believes an air field would have no adverse affect on the patients; Cooper says Sky Harbor in competition w/airport for Nashville; JDA reports 105th Observation Squadron has been flying over and landing near Asylum for several years with no adverse affect, similar situation in Washington DC - Bolling Field, Naval Air Station, St. Elizabeth's Hospital; opposition by Sky Harbor and Harris farm neighbors to Harris site; JDA proposes conference with Mayor for those who object; consider purchase property through Park Commissioners, then lease to Airport; compliments to Caldwell for his letter to Adj. Gen. Boyd; airplanes no affect on asylum inmates; ill affects of airplanes flying over State Insane Asylum in Texas, JDA's brother briefly was there;

25 Lance provides JDA with photographic negative of Col. Andrews & family at Sky Harbor visit; Riddle has been assessing airport locations in Nashville, not impressed, does not approve of Harris site, willing to meet w/JDA; Sky Harbor is a two hour round trip from Nashville, too far for convenience, summary of actions taken thus far to locate suitable site, land and prices vicinity Harris farm, fate of McConnell Field if abandoned, oil company may invest in a new field; disappointing results in bond issue vote, poor voter turnout, $1 million airport must not be wanted, but perhaps Nashville can get a suitable airport for half that amount

26 105th Observation Squadron will need to seek leased sites at Sky Harbor or Memphis, conditions of lease, minimum specs, dissatisfaction with current situation; Squadron. moves to Memphis & related fallout; JDA was schoolmate of Horton, advocates for Squadron to remain in Nashville; implication that moving squadron to Memphis is payback of election promise by Horton; advocate for squadron to remain at Sky Harbor; view of Militia Bureau from FMA; pilots prohibited from landing at McConnell Field, must use Sky Harbor; need adequate provision for squadron in order for it to remain in state with its equipment. Memphis not adequate, Sky Harbor could be, Atlanta may try to get squadron, planes cannot lawfully be used at this time; political contest between Sen. Charles Vaughn & Austin, and desire of/opposition to W.K. Abernathy for speaker of Tenn. Legislature, and political influence generally; squadron to Memphis, Federal authorities would not certify McConnell Field; FMA says Memphis field likely to lose the squadron, may be transferred to Maxwell Field in Ala., Sky Harbor could work, may be change in Tenn. governor, if so, best to have plans ready for use of Sky Harbor, FMA asks not to have his name used in this cause; hangars at McConnell orig. came from Ark. and Memphis then to Blackwood

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 46

then to McConnell by C.G. Pearcy, includes cost; 30th Div. Aviation, Militia Bureau; Memphis fails to meet requirements for squadron; JDA urges Horton to bring squadron to Sky Harbor; Fitzhugh could become governor, if so, he is from Memphis and would not be inclined to remove squadron from Memphis, Memphis not meeting requirements, may be flying w/o authority, Sky Harbor already meets requirements

28 Advocacy of Airport Commission bill in state legislature as proposed amendment to Nashville City charter, modeled after Park Commission providing for eminent domain acquisition of land; reference to 1929 act (S.B. 327, Chap. 204, Private Acts) concerning acquisition of land by Nashville for airport; concern about legality of any such act that it could withstand a court challenge; air mail; encourage Howse to convert Airport Committee into an Airport Commission; Andrews' frustration with slow response from Howse about Andrews' proposals

34. Summary of Senate Bill 1140, Chap. 17 (1931) enabling cities to establish airports, incl. condemning land if necessary; FMA's support for a new airport; notes concerning land near Bogle Rd. and Stones River Rd.

35 Note about transition from McConnell Field to Harris farm site incl. income from leases; typed summary of meeting between JDA, Mayor Howse, Mr. Centner of Aeronautics of U.S. Dept. of Commerce, and others about McConnell Field and

______________________________________________________

James D. Andrews Papers:

Series II. Frank Maxwell Andrews Series, 1908-c.1950 (bulk 1929-1943)

Collection Summary

Creator: James David Andrews, collector

Title: Frank Maxwell Andrews Series

Inclusive Dates: 1908-c.1950 (bulk 1929-1943)

Summary/Abstract: Manuscripts, including some correspondence, periodicals, newspaper clippings, and related materials about the military career of Army Air Corps general and Nashville, Tenn. native, Frank Maxwell Andrews.

Physical Description/Extent: .6 cu. ft.

Series: Frank Maxwell Andrews Series

Linking Entry Complexity Note: Forms part of the James D. Andrews Papers. Accession Number: Acc. RT-100

Language: In English.

Stack Location: Closed stacks SCC workroom range 1 section 3

Repository: Special Collections Division, Nashville Public Library, 615 Church St., Nashville, TN 37219

CHRONOLOGY

1884 Feb. 3 Frank Maxwell Andrews born to James D. and Lula Adaline Maxwell Andrews in Nashville, Tenn.

1887 Dec. - Brother James D. Andrews, Jr. born.

1888 Aug. - Brother William Valery Andrews born.

1892 July - Sister Josephine Andrews born.

1901 - Graduates from Montgomery Bell Academy.

1902 - Enters U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y.

1906 - June- Graduates from U.S. Military Academy with rank of second lieutenant. 1906 1906 - Served with 8th Cavalry Regiment in Philippines.

1907 Apr. - Began service with unidentified cavalry unit at Ft. Yellowstone Wyo. Served at Ft. Huachuca, Ariz.

1910 Oct./Nov. - Stationed at Ft. Meyer, Va.

1911 Jan. - Began serving for 3 years as aide to Brig. Gen. Macomb at Schofield Barracks, Honolulu, Hawaii.

1912 Nov. 12 - Promoted to first lieutenant.

1913 July - Returned to mainland U.S. serving with 2nd Cavalry at Ft. Bliss, Tex.

1913 Dec. - Stationed at Ft. Ethan Allen, Vt., meets Jeanette Allen, daughter of Gen. Henry T. Allen.

1914 Mar. 18 - Marries Jeanette Allen.

1916 July 15 - Promoted to captain.

1917 Apr. 6 - The United States enters World War I.

1917 Aug. 5 - Transferred to Signal Corps for duty with Aviation Division.

1918 July - Earned wings as Junior Military Aviator at age 34, considered old.

1918 Oct. - Supervisor of Southeastern Air Service District headquartered in Montgomery, Ala.

Page 2

Frank M. Andrews Series:

Page 2 of 16

James D. Andrews Papers

1918 Nov. 11 World War I ends.

1920 Aug. 14 Sent to Germany as part of Occupation forces

1923 June - 1927 Sept. Stationed at Kelly Field, Tex.

1929 Aug. Held rank of major and was executive officer in the office of Chief of Air Service, Washington, DC.

1930 Jan. 13 Promoted to lieutenant colonel.

1931 May Held rank of Lt. Col., chief of staff, operations and training divisions, U.S.Army Air Corps, Washington DC.

1932 Apr. Held rank of Col.

1932 Apr. 19 Lula Maxwell Andrews dies.

1935 Mar. 1 Became first Commanding General of GHQ Air Force with temporary rank of Brig. Gen.

1935 Spring Andrews makes statement to a 'secret session" of the House of Representatives that U.S. must be prepared, if necessary, to take over bases in other countries if they were in danger of being taken over by forces of enemies of the U.S. His statement is leaked to the press, causing a public outcry and denied as Army policy by Army officials, ultimately resulting in Andrews' censure by President Roosevelt.

1935 Aug. 24 Sets three world's records in a seaplane for speed without payload, speedwith payload of 500 kg, and speed with payload of 1000 kg, breaking all three records previously held by Charles Lindbergh.

1935 Dec. 26 Temporarily promoted to major general.

1936 Feb. 22 Serving as commanding general of General Headquarters Staff, American Air Force, Frank M. Andrews stops at Sky Harbor airport near Murfreesboro, Tenn. in his "office plane" and meets with his father.

1936 June 14 Nashville hosts celebration for Frank M. Andrews, including a reception, barbecue, and "sham battle" held on the estate of Col. Henry Dickinson.

1936 Nov. 1 Attends dedication ceremonies for new Nashville Municipal Airport (Berry Field).

1937 Mar. 4 James D. Andrews dies.

1937-1938 Participates in "war games" using air power against naval forces.

1939 Mar. Tour of duty as Commanding Gen. of GHQ completed and returned to permanent rank of colonel, sent to Ft. Sam Houston, Tex.

1939 July 1 Promoted to brigadier general by Gen. George C. Marshall and served on War Dept. General Staff in Washington, under Marshall.

1940 Nov. In command of Panama Canal Air Force.

1941 Sept. Became first air commander to head a joint forces organization when hebecame commander of Caribbean Defense Command and Panama Canal Department. The command system he established there was used as a model and advocated by Chief of the Army Air Forces, Gen. H.H. "Hap"Arnold.

1941 Dec. 7 The United States enters World War II after the Japanese attack Pearl Harbor, Territory of Hawaii.

1942 Nov. Andrews becomes commander of all U.S. forces in the Middle East.

1943 (early) Andrews becomes commander of U.S. forces in Europe, headquartered in London.

------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 3

Frank M. Andrews Series:

Page 3 of 16

James D. Andrews Papers

1943 May 3 Dies in plane crash in Iceland; buried at Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Va.

1943 June 14 Dedication of Andrews Blvd. in Nashville, named in his honor.

1944 Feb. Dedication of airfield in Dominican Republic, named in his honor.

1945 Camp Springs airbase in Maryland renamed Andrews Field in his honor.

1947 Andrews Field name changed to Andrews Air Force Base.

Biographical/Historical Sketch:

Frank Maxwell Andrews was born on Feb. 3, 1884, the first child of James D. and Lula Maxwell Andrews of Nashville, Tenn. All three of James D. Andrews's sons, Frank (or "Maxwell" as he was called in the family), James D. Andrews, Jr. (probably known as "David") and William Valery Andrews would go on to have military careers. He had one sister, Josephine, who later married Nashvillian Gillespie Sykes. Frank Maxwell Andrews attended public schools until the age of 13, when he entered Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville, graduating in 1901. The following year, he entered the United States Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., where he graduated in 1906 with the rank of second lieutenant. He was sent to serve with the 8th Cavalry Regiment in the Philippines. He returned to the United States about a year later, serving briefly in Wyoming, Arizona, and Virginia. In 1911, he became an aide to Brigadier General Macomb at Schofield Barracks in Hawaii, and returned to the United States mainland in the summer of 1913. He married Jeanette Allen on Mar. 18, 1914. Both Frank and Jeanette, who went by the nick name, "Johnnie," were avid polo players. She was the daughter of General Henry T. Allen. Allen, sensing Andrews's growing interest in aviation, declared no aviator would ever marry his daughter. Andrews remained in the cavalry for a time, but after several years of married life, in 1917, he joined the Signal Corps serving in the Aviation Division. Although considered old for an aviator, he nevertheless rapidly advanced in rank and responsibility. In 1918, he became supervisor of the Southeastern Air Service District. After World War I, he served in Germany as part of the Occupation, and commanded air forces under his father-in-law, Maj. Gen. Henry T. Allen. He returned to the United States sometime in the early 1920s, and he continued to advance in his career. On Mar. 1, 1935, he became the first Commanding General of GHQ Air Force, with the temporary rank of Brigadier General. His work in this capacity established the modern Air Force. Key innovations were the consolidation of all Army Air Forces under one overall command, the development of regional air commands, and improved training and strategic planning, especially in the strategic and tactical uses of bombers. In 1935, he set three new world records for speed in a seaplane, breaking the records held by Charles Lindbergh. Also in 1935, he caused an uproar when he stated before a House of Representatives secret session that it might be necessary for American forces to seize airbases of other countries if they were in danger of becoming a threat to the United States. The statement was leaked to the press, the Army denied such a policy, and President Roosevelt censured him. This difficulty did not, however, ultimately affect his career. He returned to Nashville numerous times, and was honored in June 1936 by Col. Henry Dickinson, who hosted a large community barbeque for him. He also spoke as a visiting dignitary at the dedication of the new Nashville Municipal Airport in 1936. In March 1939, his duties at GHQ ceased and he was returned to the rank of colonel, though four months later he was given the permanent rank of brigadier general

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 4

Frank M. Andrews Series:

Page 4 of 16

Last updated: 6/17/2009

James D. Andrews Papers

by Gen. George C. Marshall, serving on the War Department General Staff in Washington, DC. In 1940, he was given command of the Panama Canal Air Force, and in 1941 became the first air commander to head a joint forces operation. As World War II got underway, Andrews was promoted to even higher positions of authority. In November of 1942, he became commander of all U.S. forces in the Middle East; and in early 1943, he was sent to Europe with similar authority. On May 3, 1943, he died in a plane crash in Iceland, along with Methodist Bishop Adna W. Leonard, Brig. Gen. Charles Barth, Col. Morrow Krum, and others; only one man survived. Andrews received many posthumous honors, including the addition of an oak leaf cluster to his Distinguished Service Medal; the renaming of an airfield in Maryland in his honor (which was subsequently renamed Andrews Air Force Base in 1947); the naming of an airfield in the Dominican Republic in 1944; and the dedication of a street in his hometown of Nashville, Tenn. He was survived by his wife, Jeanette, and three children: Allen, Josephine (Mrs. Hiette S. Williams Jr.); and Jean, who was unmarried at the time of his death, but later married Martin F. Peterson. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

Scope and Contents of the Collection

Manuscripts, including some correspondence, periodicals, newspaper clippings, and related materials about the military career of Army Air Corps general and Nashville, Tenn. native, Frank Maxwell Andrews, most dating from 1929-1943, although some items are as early as 1908 or as late as circa 1950. The manuscripts subseries primarily consists of periodicals featuring articles about Andrews and his military career. A few other items, such as tickets and invitations are also included in this subseries. There is a small amount of correspondence, although most items of this nature have been pasted-over with newspaper clippings. Nevertheless, some of the original letters can still be read, at least in part. Clippings document Andrews's career in great detail, provide numerous anecdotes, and include information about his wife, Jeannette, and her father, Gen. Henry T. Allen. Information on other Andrews family members, such as Frank Maxwell Andrews's parents, James D. and Lula Andrews, and his siblings, James D. Andrews, Jr., William Valery Andrews, and Josephine Sykes, is also included.

Clippings are especially strong about Andrews's actions and influence during his assignments in the Panama Canal Zone and Caribbean, with GHQ Air Force, and the uproar caused by his statements before a House Committee in which he recommended taking over airbases in French and British possessions if America was threatened by enemy troops holding those bases. There are also numerous accounts about his death in a plane crash in Iceland in 1943, along with Methodist Bishop Adna W. Leonard, Brig. Gen. Charles Barth, and Col. Morrow Krum who also died. A few clippings provide information about Andrews's involvement, with his father, in the push to get a new airport for Nashville, Tenn.; a visit to Sky Harbor airport near Murfreesboro, Tenn. in 1936; and a grand celebration in his honor hosted by Col. Henry Dickinson of Nashville in 1936, where he was awarded a trophy. Some clippings also discuss Army Air Corps training, war games, planes, strategy, and reorganization, as they relate to Andrews's career and influence.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 5

Frank M. Andrews Series:

Page 5 of 16

Last updated: 6/17/2009

James D. Andrews Papers

Researchers are advised to consult Series I: James D. Andrews Series of this collection, which documents in more detail Frank Maxwell Andrews's efforts on behalf of his father's actions to obtain a new airport for Nashville. The younger Andrews often provided advice, specifications, and opinions about sites under consideration for a new airfield. He also assisted by providing information about the affect of airplanes on patients in insane asylums, an issue which threatened to stall or kill plans to develop the Harris farm site, near the Central State Hospital in Nashville. Series I also contains some personal correspondence between father and son, in which Frank Maxwell Andrews occasionally discusses places where he is stationed, his family, or other subjects. Researchers should check the finding aid to Series I for more details.

One newspaper article from Series III: Miscellaneous Nashville Subjects, is included in this finding aid, since it concerns Frank Maxwell Andrews. In addition to the biographical information on Frank Maxwell Andrews, there are a number of articles or anecdotes which relate to his two brothers, James D. Andrews Jr. who served in the engineers, and William Valery Andrews, who was also in Army aviation. Especially noteworthy is a clipping from Nov. 1941 (Folder 79) in which William Valery Andrews states that the Japanese population of Hawaii would be loyal to the United States in the event of war between the U.S. and Japan.

Organization/Arrangement of Materials

The collection is organized into the following series:

I. James D. Andrews Series

II. Frank Maxwell Andrews Series

III. Miscellaneous Nashville subjects

This finding aid concerns only Series II. Additional finding aids are available for other series. Series II is divided further into the following subseries by format:

A. Manuscripts, 1921-c.1950 (no arrangement scheme)

B. News clippings, 1908-1946 (bulk 1930-1943) (no arrangement scheme)

Some items are very fragile, and must be handled with care.

Index Terms

Personal Names:

Allen, Henry T. (Henry Tureman), 1859-1930

Andrews, Frank Maxwell, 1884-1943

Andrews, James David, 1857-1937

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 6

Frank M. Andrews Series:

Page 6 of 16

Last updated: 6/17/2009

James D. Andrews Papers

Andrews, James David, b. 1887

Andrews, Jeanette (Jeanette Allen) Andrews,

Lula Maxwell, 1859-1932

Andrews, William Valery, b.1888

Barth, Charles Henry, d. 1943

Dickinson, Henry, Colonel

Krum, Morrow, d. 1943

Leonard, Adna W., d. 1943

Sykes, Josephine (Josephine Andrews), b. 1892

Corporate Names/Organizations:

General Andrews Airport (Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic)

Montgomery Bell Academy (Nashville, Tenn.) -- Alumni and alumnae --Biography

Sky Harbor (Airport : Murfreesboro, Tenn.)

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 7

Frank M. Andrews Series:

Page 7 of 16

Last updated: 6/17/2009

James D. Andrews Papers

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 8

Frank M. Andrews Series:

Page 8 of 16

Last updated: 6/17/2009

James D. Andrews Papers

Two additional photographs concern Frank Maxwell Andrews, but their provenance is unknown. They may or may not have originally been a part of the original Andrews Papers. They are part of the Nashville Room Historic Photographs Collection and are identified as follows:

P-95 Lt. Gen. Frank M. Andrews, in uniform, outdoors at unidentified location, car and building behind him.

P-1961 Trophy cup presented to Frank M. Andrews.

Immediate Source of Acquisition: Source of acquisition unknown, but donated probably before 1980.

Ownership and Custodial History: Unknown provenance. Many materials probably collected by James D. Andrews, although a number of items are dated after his death. Some materials may have been collected by the sister of Frank Maxwell Andrews, Josephine Sykes.

Processing Information: Collection was originally physically housed in the library in three different areas: Persons Ephemera Subject Files; closed stacks shelf; oversize drawer. No original order was discernable within the materials. Materials were consolidated into one collection and artificially organized into three series by Library staff, and rehoused in appropriate storage containers. Accruals: No further accruals are expected.

Other Finding Aids

See additional finding aid for Series I – James D. Andrews and Series III – Miscellaneous Nashville subjects

References to Works by or about Collection Creator/Topic The Tennessee State Library and Archives holdings include the William Valery Andrews Papers. William was Frank Maxwell Andrews's brother. A biography by DeWitt S. Copp entitled Frank M. Andrews: Marshall's Airman (Washington, D.C.: Air Force History and Museums Program, 2003) is available online (as of Apr. 2009) at: http://www.airforcehistory.hq.af.mil/Publications/fulltext/FrankMAndrews.pdf

Detailed Description of the Collection

Series II. Frank Maxwell Andrews Series, 1908-c. 1950, .6 cu. ft.

---------------------------------------------------------------

Page 9

Frank M. Andrews Series:

Page 9 of 16

Last updated: 6/17/2009

James D. Andrews Papers

Sub-series A.

Frank Maxwell Andrews Manuscripts, 1921-c. 1950, .2 cu. ft. Series Abstract/Description: Manuscripts, including some correspondence and numerous periodicals containing articles about Frank M. Andrews and his military career.

Arrangement: No arrangement scheme

Container List: Folders 60-71, 77-78 Sub-series B. Frank Maxwell Andrews Clippings, 1908-1946 (bulk 1930-1943), .4 cu. ft. Series Abstract/Description: Newspaper clippings, many from the Nashville Banner, and Tennessean, but including a number of other newspapers from other cities, concerning the military career of Frank M. Andrews. His promotions and numerous special assignments are well-documented, and a significant portion of the clippings are about his death and posthumous honors.

Arrangement: No arrangement scheme

Container List: Folders 71-74, 79, 82-841 item in Folder 85, part of Series III and concerning Frank M. Andrews, is described below.

Container List Abbreviations:

FMA = Frank Maxwell Andrews

JDA = James D. Andrews

Subseries A – Manuscripts

Folder Summary of contents

60 Admission ticket to General Andrews Day at Col. Dickinson's farm, June 14, 1936; menu & program from Mid-South Section of American Society of Civil Engineers meeting Oct. 25, 1940; paper from dedication of Andrews Blvd. June 13, 1943; V-mail from Joe Thompson Jr. to "Cousin Josephine" Sykes, May 9, 1943, telling of his meeting w/Gen. Andrews and reaction to Andrews' death.

61 The Ground Ace, Apr. 1, 1921, vol. 1 no. 1, published in Weissenthrum, Germany. Cover photo of Maj. Frank M. Andrews "Our Chief."

62 "Notice to Aviators," May 1, 1921, No. 5, U.S. Navy Dept. Information about various landing fields in the United States, markings, use of radio & pigeons.

63 The Reserve Officer, Jan. 1935, vol. 12, no. 1, U.S. Army. Article: "Air Force Commander Plans Maneuvers."

------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 10

Frank M. Andrews Series:

Page 10 of 16

Last updated: 6/17/2009

James D. Andrews Papers

64 The National Aeronautic Magazine, Feb.-Mar. 1935, vol. 13, no.2 & 3, National Aeronautic Association. Article: "Our New GHQ Air Force."

65 U.S. Air Services: Feature Aeronautical Magazine, Commercial and Military, May 1935, vol. 20, no. 5, Air Service Publishing, Inc. Cover photo of Brig. Gen. Frank M. Andrews, Commander of GHQ Air Force, and article, "Significance of the General Headquarters Air Force" by Lt. Col. John D. Reardan.

66 The Bee-Hive, Oct. 1935, vol. 9 no. 10, United Aircraft Corporation. Article: "General Andrews Sets World's Records with Hornet-powered Martin Bomber."

67 Time magazine, July 29, 1940, vol. 36, no. 5. Article: "National Defense," includes profile of Brig. Gen. Frank M. Andrews.

68 The American Legion Magazine, March 1942, vol. 32, no. 3. Article: "Leading the Army Team," includes profile of Lt. Gen. Frank M. Andrews.

69 Air Force: The Official Journal of the Air Force Association, Sept. 1947, vol. 30, no. 9.

70 Unidentified notes or essay about the worldwide political consequences of World War II, c. 1950

71 This folder, although part of the clippings subseries, contains some manuscripts. Clippings have been pasted on to manuscript letters, presumably written by FMA. Portions of the letters are legible, but much is obscured by clippings. Letters date from 1930-1932. from Washington, DC Dec. 9, 1930, FMA to mother: Reference to David (perhaps James D. Andrews Jr.) stationed in Panama, having sinus difficulties, may return to States; F---? Field, possibly located in Central or South America, near Panama, or in Washington DC; Apr. 3, 1932, FMA to JDA: tells of flying over jungle so thick that the ground could not be seen, mentions Guatemala; unidentified fragment of letter, possibly continuation of previous: Costa Rica, Panama, will start for New York Apr. 16 [1932?] in the Republic [airplane?]; from Washington DC July 14, 1931, FMA to JDA: "Judith, David and the children" were at "our bachelor house" for dinner, played bridge, David looks well but still complains of ailments but expects to get out of hospital soon, Nelson has recovered from his operation; from Mather Field, Sacramento, Calif. Apr. 6, 1930, FMA to JDA: "I am glad to know that the board of experts recommended the Harris farm. You may get a big sale out of it." put on a show in San [Francisco? Fernando?]

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 11

Frank M. Andrews Series:

Page 11 of 16

Last updated: 6/17/2009

James D. Andrews Papers

77 The War Cry Feb. 1932, includes photograph of FMA and father JDA at Sky Harbor, Tenn.

78 London Calling, June 6-12, 1943, article, "HQ ETOUSA," notice of FMA's death as going to print Subseries B - Clippings

71 Dates: 1908-09, 1917-18, 1921, 1923-24, 1928-29, 1930-33, 1935-37,1946 Newspapers: Tennessean, Nashville American, Nashville Banner, Washington Post, Dayton Journal, Chicago Daily Tribune, (unidentified)Shreveport, Louisiana Subjects: FMA promotion from Maj. to Lt. Col. and from Col. to Maj. Gen.; FMA flights in U.S. and Europe, incl. Coblenz, Germany to London, England; seaplane record attempt by FMA; visits by FMA to parents in Nashville; FMA's opinions on Nashville airport; FMA's family incl. wife and son; FMA visits Cuba; airplanes flown by FMA; Lt. J.D. Andrews Jr. sent to Europe as engineer in rebuilding efforts; FMA directs war games and maneuvers at Dayton, OH and Chicago, IL; Johnnie Andrews & women's polo; FMA meets with Ray Murphy of American Legion; FMA promoted to Maj. and transfers from cavalry to aviation; FMA service with 8th Cavalry; various promotions of FMA; death, funeral, obituary of Charles Sykes, Gillespie Sykes, and Lula Andrews. Persons & Businesses: FMA; JDA; JDA Jr.; Johnnie Andrews (FMA's wife); Ray Murphy, National Commander American Legion; Gillespie Sykes; Charles Sykes; Lula Andrews.

Locations: Cuba; San Antonio, TX; Dayton, OH; Coblenz, Germany; London, England; McConnell Field, Nashville, TN; Sky Harbor, Murfreesboro, TN; Washington, DC; Chapman Field, Miami, FL; Barksdale Field; Fort Ethan Allen, VT; Yellowstone National Park; Fort Yellowstone; Panama; Central America; South America; Mather Field, Sacramento, CA; Guatemala; Costa Rica; San Francisco or San Fernando, CA; Harris farm site, Nashville, TN; Maps, Photos, Illustrations (in newspapers): Photos of Johnnie (Mrs. Frank M.) Andrews; Col. FMA and airplanes on maneuvers; Gillespie Sykes; Charles S. Sykes.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 12

Frank M. Andrews Series:

Page 12 of 16

Last updated: 6/17/2009

James D. Andrews Papers

Notes: Many clippings have been pasted on to manuscript letters, presumably written by FMA. Portions of the letters are legible, but much is obscured by clippings. For details, see entry for this folder in Manuscripts Subseries.

72 Dates: 1930, 1934-37 Newspapers: Nashville Banner, Tennessean, Washington Herald, Presbyterian Tribune Subjects: 27th Pursuit Squadron of First Pursuit Group stops at Sky Harbor under command of FMA; FMA's "air office" plane; FMA as head of GHQ Air Force; Andrews family history provided and controversy and defense of FMA's statements concerning war appears in Presbyterian Tribune article; Baker Board (results in formation of GHQ); R.O.T.C. in Nashville high schools; Barbeque hosted at Col. Henry Dickinson's farm in honor of FMA

Persons/Businesses: FMA, JDA Locations: Sky Harbor; Nashville high schools Maps, Photos, Illustrations (in newspapers): FMA, JDA, Mrs. JDA, FMA's sister Mrs. Gillespie Sykes; airplanes in formation, photo of trophy presented to FMA by Nashville citizens

73 Dates: 1921, 1930-32, 1934-36, 1939, 1942 Newspapers: Tennessean, Nashville Banner, San Francisco Examiner, Miami Herald, Washington Post, Pathfinder, New York Times Magazine, San Diego Union, Miami Daily News

Subjects: FMA's testimony before House committee that US may need to seize British and French possession in time of war & breach of secrecy by Rep. John Jackson McSwain, related uproar; Capt. William V. Andrews with British Squadron leader Carnegie at Bolling Field; tribute to FMA(after his death); FMA promoted to Maj. Gen.; breaking of 3 world records by FMA; war games and maneuvers in California and Miami; description of flight from Coblenz, Germany to London, England; biographical sketches of JDA and his three military sons; establishment of GHQ Air Force; statements by FMA on various subjects incl. readiness, strategy, defense; address to National Aeronautic Association about U.S. mainland defense and state of the Air Force; inspection of Panama Canal Zone defenses by Sec. of Navy.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 13

Frank M. Andrews Series:

Page 13 of 16

Last updated: 6/17/2009

James D. Andrews Papers

Persons/Businesses: FMA, JDA, William V. Andrews; JDA Jr.; Sec. Navy Frank Knox; Rear Adm. Clifford Evans Van Hook; Rep. John Jackson McSwain of SC.

Locations: Caribbean; Bolling Field; Panama Canal Zone; Coblenz, Germany; London; Miami, Florida; California. Maps, Photos, Illustrations (in newspapers): FMA, JDA, JDA Jr., William V. Andrews, air dignitaries and officers, Sec. Navy Frank Knox, Rear Adm. Clifford Evans Van Hook

74 Dates: 1925, 1937, 1943

Newspapers: Memphis Press Scimitar; Cincinnati Times-Star; Nashville Banner; Memphis Commercial Appeal; New York Herald Tribune; unidentified San Diego newspaper; New York Times; unidentified St. Louis newspaper; Subjects: Death of JDA; death of Lula Andrews; deaths of FMA, Methodist Bishop Adna W. Leonard, Brig. Gen. Charles Barth, Col. Morrow Krum and others in crash in Iceland; dedication of airfield in Dominican Republic in FMA's name; posthumous award of Oak Leaf Clusters and Distinguished Service Medal to FMA; FMA's burial in Arlington National Cemetery

Persons/Businesses: JDA; Lula Andrews; FMA; Bishop Adna W. Leonard; Brig. Gen. Charles Barth; Col. Murrow Krum

Locations: Iceland; Arlington National Cemetery; Dominican Republic Maps, Photos, Illustrations (in newspapers): FMA; Bishop Leonard

79 Dates: c. 1929, 1935-36, 1940-42 Newspapers: Spartanburg (SC) Herald, Banner, Tennessean, Denver Post, Collier's, New York Times, Memphis Commercial Appeal, Baltimore Sun Subjects: FMA's courtship, marriage, and honeymoon "on horseback" father-in-law objected to aviator so he went to cavalry; Gen. Hq. Air Force to be established at Langley Field, FMA to command; FMA assumes command of GHQ AF (1000 planes unified from throughout country); FMA visits Lowry Field, Denver; Col. William V. Andrews says Japanese in Hawaii would be loyal if war comes between U.S. & Japan, Nov. 1941;

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 14

Frank M. Andrews Series:

Page 14 of 16

Last updated: 6/17/2009

James D. Andrews Papers

Lt. Gen. FMA commander in Canal Zone; Flying Fortresses and training and organization under FMA; Brig. Gen. FMA, Lt. Col. JDA Jr., Lt. Col. William Valery Andrews to speak at American Society of Civil Engineers Mid-South Section in Memphis (Oct. 25, 1940); sham battle hosted at estate of Col. Henry Dickinson in FMA's honor; report of Lt. Gen. FMA on anti-submarine measures taken in Caribbean, incl. photojournalist's eyewitness account of attack by sub near Aruba

Persons/Businesses: FMA; Jeanette Allen (wife); Maj. Henry T. Allen(father-in-law); Col. William V. Andrews; Lt. Col. James D. Andrews Jr.

Locations: Langley Field, VA; Lowry Field, Denver, CO; Hawaii; Panama Canal Zone; Memphis; Sky Harbor, Murfreesboro, TN; Nashville Municipal Airport; Caribbean; Aruba

Maps, Photos, Illustrations (in newspapers): FMA as cadet at West Point and with father, JDA; numerous military photos of FMA; photo of airplanes in formation over Capitol at Washington DC; all 3 Andrews brothers together in Memphis; sham battle at Col. Dickinson's estate in Nashville.