The grave of John's mother, the former Delilah Alexandra Kea has yet to be located. She is presumed to be buried in the Darlington County area, and is estimated to have died around 1851 in Darlington County. His father is buried in Newman Swamp United Methodist Church cemetery, listed on Find-A-Grave as "Newman Swamp Cemetery".

In 1932, John Alexander dictated a shortened version of his life story to his daughter Maggie Louise Alexander, a schoolteacher who knew he had a lot to say about some of the historical events of the War Between the States. This is his "Reminiscence".

"I was born August 26, 1846, in Henry County, Alabama. My parents emigrated from Alabama when I was about three years old. My mother died when I was about four years old, so I have never known the love of a mother.

In writing this, I wish to relate some of the most impressive experiences of my life as a soldier during my four years of service in the War Between the States as best I can remember them now.

I was too young to realize what I was getting into when I entered the war. I had a pal, John W. DuBose, who was older than I. He had enlisted for service, and as I loved him dearly, I could not bear for him to leave me. It was because of his influence that I volunteered to go to the army, as I was not quite fifteen years of age. My pal and I were in all the conflicts.

I entered the war in 1861. W.I. Carter of Cartersville was my captain, his company A, 14th South Carolina Regiment. We were trained for service at a place called Lightwood Knot Springs, near Columbia, South Carolina. I was in training about three months, served on the coast about Beaufort Island until the second day of May, 1862.

The Northern troops were encamped on Beaufort Island. We had several skirmishes around and near Port Royal and Beaufort Island. In these skirmishes, very few lives were lost. On the twenty-second day of May, 1862, we got orders to go to the Northern Army at Richmond, Virginia.

A short while after this we went into hostilities. The comptroller of the Northern Army was General McClellan. Among those in my company were my pal, John W. DuBose, Sewell W. DuBose, Henry DuBose, George Scarborough, Marion Large, Charlie and Alexander Stuckey.

Alexander Stuckey was an orderly sergeant. He was wounded at The Battle of the Wilderness. A minnie ball struck him on one side of the head going through it and came out on the other side. I reported him as dead. He was taken to some hospital and recovered. Sewell DuBose was a brave soldier. After the war, he married Elizabeth Gwynn Jenkins, and reared a large and intelligent family of children. Marion Large married a daughter of Sewell DuBose.

At the beginning of the war, my only brother, Abner Alexander, enlisted for service for six months. He fought in the first Battle of Bull Run, Virginia. Six months he came home and found that I had entered the army. He regretted, very much, that I had taken this step. I went away while he was at home. My brother re-enlisted and went back to the same company. Just a few days before they went to Tennessee, I heard that my brother's command was about a mile from me. I got permission to go to him, and this was the last time I ever saw him. He came a part of the way back with me. We sat on a chestnut log and he told me that he felt like that we would never see each other again, and told me, also, where I would find his trunk and other belongings. He was killed at Lookout Mountain, Tennessee. I found his things, as he told me, his trunk and picture, but his girlfriend refused to part with his jewelry.

The first battle I engaged in was The Battle of Seven Pines. This battle took place along the Chickahominy River, and was as complete a victory as the Southern Army ever had. We drove twenty-seven miles down the river until we were under the shelter of their gunboats that lay in the James River. At this time our brigadier general was Maxcy Gregg of Florence, South Carolina, who was one of the bravest men I ever knew. Later I saw him, after he was killed, being carried on a stretcher at The Battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia. I do not know how old General Gregg was at the time of his death, but he looked to be about forty years old. From this time the battles were too numerous for me to remember the dates.

I fought in the following divisions: I fought under General A.P. Hill, General Maxcy Gregg, Abner Perrin. I was never wounded bad enough to leave the battlefield, but was knocked down by a ball at Vine Run, Virginia. I had a small camp Testament in my pocket which I think saved my life. The ball hit me in the region of my heart, doubling the Testament in the center. I was knocked down, was stunned, but soon got up and took my place in the battle.

At The Battle of Cold Harbor we fought all afternoon until dark. When the battle ceased, I was detailed to go to the rear and get water for the company. Taking as many canteens as I could carry, I went to a little ravine to get water. A Union soldier was lying near the ravine. His teeth had been shot out and his jawbone was broken. He made me understand that he wanted water. I held the canteen to his lips and he drank all he wanted. After this, he made me understand that he wanted me to carry him to the rear, as we were still in danger. I carried him about three hundred yards and left him. When I returned to my company, I was sent to help bring the dead. We worked all night until up into the next day.

I was in the Battle of Gettysburg, which lasted four days and nights. This was the most cruel of all the battles. It was a slaughter pen. I was a drummer boy at this time, and after three or four rounds of fighting, the bass drummer and I were detailed to care for the wounded. The Battle of the Wilderness was a thick forest of junipers which were hewn down by balls like a field of grain. It did not seem that a person could come out the battle alive.

Twice during the war I was dangerously ill. I had typhoid fever, also typhoid pneumonia. One day I was sent to Richmond, Virginia, a distance of about twelve miles, to drive cattle for beef for the army. On my way back to camp, a thundercloud arose, and I lay in a wet blanket that night in mud and water. When I awoke the next morning I was very sick. Two days later, my commander was sent to Fredericksburg, Virginia and I was sent to a hospital in Lynchburg, Virginia. I had developed typhoid fever. One Sunday morning while convalescing, two of us decided to ask permission of the doctor to let us take a walk. He agreed, on the condition that we would not eat anything on the trip. We promised. On our trip we saw a garden of beautiful green collards and asked a colored woman to cook some of them for us. This she did, and we ate all we wanted with no bad results.

At Malvern Hill I was captured prisoner. From there was sent to Point Lookout, and from there was sent to Elmira, New York.

This was a very bitter experience. As it was very cold, the prisoners suffered severely from cold and hunger. Here, I contracted typhoid pneumonia and again, was dangerously ill. When I had about recovered, I got an exchange payroll. When I left prison they gave me a piece of pickled pork and hard tacks to eat. I would have died from hunger, but got up with some officers, who shared what they had with me.

I left Elmira, New York the 14th of March 1865, and reached my home on the 27th of March. I came home by way of Richmond, and came by railroad to Blackstock, South Carolina. The Union Army had torn up the railroad, and I had to walk the rest of the way, a distance of one hundred and ten miles. When my partner and I reached the Wateree River, we made an attempt to cross over without the help of the ferryman, and had a narrow escape from drowning. But the ferryman arrived and carried us safely over.

The first night after reaching Camden, I spent the night with a cousin who sent us a part of the way home the next morning. Sherman's Raid had passed through this country and had destroyed everything. "Life preserver peas" were about the only thing that could be had, and the people said that they had the right name.

On arriving home, I heard that my cousin, Edward Alexander, who served in the Western armies, who had been reported and lamented as dead for three years, had returned home two weeks previous. His funeral had been planned, and a preacher engaged to preach his funeral on the Sunday following his arrival on Friday night. On this Sunday, this soldier went to the service and told the preacher he need not bother about preaching his funeral.

I was in a company of one hundred and twelve men, and as far as I know, am the only living one at the present time. I was never wounded in the war, but soon after, I had the misfortune to get my leg broken twice in the same place. From this accident I have never recovered, but the results have followed me until the present time.

I am now in my 87th year. I have six children living, thirty-nine grandchildren, thirty-two great-grandchildren, and one great-great grandchild. I am also the only one of my family of the older Alexanders living now. (signed) John Wesley Alexander"

Obituary from "Florence Morning News", and believed to have written by John Alexander's daughter, Maggie Louise Alexander:

"Taps for Brave Soldier Sound

Funeral Services for John W. Alexander at Timmonsville Today

Special to Morning News:

TIMMONSVILLE, Feb 14 - Funeral services for John W. Alexander, 87, gallant Confederate veteran who died Tuesday night at his home a few miles from Timmonsville, will be held Thursday morning 11 o'clock from the Pine Grove Methodist church conducted by his pastor, the Rev. J.F. Campbell. Interment will follow in the Thornwell Cemetery (Thornal is correct) beside the grave of his wife.

Mr. Alexander enlisted in the Confederate army at the age of fifteen years and served throughout the war. He was a member of Culpepper Camp, U.C.V. of Timmonsville. For thirty years he had been superintendent of the Pine Grove Methodist Sunday School being assisted the last few years by his son Luther Alexander.

Mr. Alexander was a splendid Christian gentleman and his influence for good has been far reaching. His death, due to heart trouble from which he had been suffering for some time brings sorrow to a host of friends.

Surviving are two daughters, Mrs. George Hatchell and Miss Maggie Alexander and four sons; J.L., J.K., C.E. Alexander all the Timmonsville section, and H.L. Alexander of Greenville. He also leaves 32 grandchildren, 30 great-grandchildren and four 2-great-grandchildren. The passbearers will be six grandsons: Gary Hill, Roy Hatchell, Lee, Arnold, James, and Earl Alexander."

Obituary from the March 15, 1934 issue of the Methodist periodical "Southern Christian Advocate":

"On Feb 13, 1934, death came into our midst and removed from the home, church and Sunday school one of the most faithful and beloved members, Bro. John Wesley Alexander, 87 years 5 months and 17 days of age. He was the son of the late Rev. John William Alexander who died in the year 1903 (1899 is correct). His loving wife passed through the gate of death in 1917, leaving him a widower for the past 17 years.

Brother Alexander gave his heart to God around 45 years ago and had a rich experience until the day came when he fell asleep. He really did fall asleep. On Friday night preceding his death, realizing that he was soon to pass out, he called all who were near to his bedside and talked and prayed with them closing with a benediction. He then went into a state of coma and breathed his last on the following Tuesday night. He served as steward of Pine Grove Methodist Church for quite a number of years and was superintendent of the Sunday school until the day of his death. He died in harness for his Lord.

He was a member of the league of Confederacy, having served all four years in the war between the States. During the war his life was saved by a pocket Testament. A bullet, which perhaps would have pierced his heart, struck the Testament in his pocket and his life was spared.

He is survived by six children: Charlie Alexander, H.L. Alexander, J. Luther Alexander, Joseph Alexander, Mrs. G.C. Hatchell, and Miss Maggie Alexander; also 40 grandchildren, 40 great grandchildren, and 3 great great grandchildren. He is gone but not forgotten. His works do follow him. - J.F. Campbell"

John and his wife Sallie had another daughter, Ella L. Alexander Hatchell, not listed, who died in the early 1900s at age 33. Although it is theorized that she was buried in John's "Lone Tree Farm" family cemetery, not too far from Pine Grove, it has not been proven that she is buried there. There has been a lot of destruction there over the years.

The grave of John's mother, the former Delilah Alexandra Kea has yet to be located. She is presumed to be buried in the Darlington County area, and is estimated to have died around 1851 in Darlington County. His father is buried in Newman Swamp United Methodist Church cemetery, listed on Find-A-Grave as "Newman Swamp Cemetery".

In 1932, John Alexander dictated a shortened version of his life story to his daughter Maggie Louise Alexander, a schoolteacher who knew he had a lot to say about some of the historical events of the War Between the States. This is his "Reminiscence".

"I was born August 26, 1846, in Henry County, Alabama. My parents emigrated from Alabama when I was about three years old. My mother died when I was about four years old, so I have never known the love of a mother.

In writing this, I wish to relate some of the most impressive experiences of my life as a soldier during my four years of service in the War Between the States as best I can remember them now.

I was too young to realize what I was getting into when I entered the war. I had a pal, John W. DuBose, who was older than I. He had enlisted for service, and as I loved him dearly, I could not bear for him to leave me. It was because of his influence that I volunteered to go to the army, as I was not quite fifteen years of age. My pal and I were in all the conflicts.

I entered the war in 1861. W.I. Carter of Cartersville was my captain, his company A, 14th South Carolina Regiment. We were trained for service at a place called Lightwood Knot Springs, near Columbia, South Carolina. I was in training about three months, served on the coast about Beaufort Island until the second day of May, 1862.

The Northern troops were encamped on Beaufort Island. We had several skirmishes around and near Port Royal and Beaufort Island. In these skirmishes, very few lives were lost. On the twenty-second day of May, 1862, we got orders to go to the Northern Army at Richmond, Virginia.

A short while after this we went into hostilities. The comptroller of the Northern Army was General McClellan. Among those in my company were my pal, John W. DuBose, Sewell W. DuBose, Henry DuBose, George Scarborough, Marion Large, Charlie and Alexander Stuckey.

Alexander Stuckey was an orderly sergeant. He was wounded at The Battle of the Wilderness. A minnie ball struck him on one side of the head going through it and came out on the other side. I reported him as dead. He was taken to some hospital and recovered. Sewell DuBose was a brave soldier. After the war, he married Elizabeth Gwynn Jenkins, and reared a large and intelligent family of children. Marion Large married a daughter of Sewell DuBose.

At the beginning of the war, my only brother, Abner Alexander, enlisted for service for six months. He fought in the first Battle of Bull Run, Virginia. Six months he came home and found that I had entered the army. He regretted, very much, that I had taken this step. I went away while he was at home. My brother re-enlisted and went back to the same company. Just a few days before they went to Tennessee, I heard that my brother's command was about a mile from me. I got permission to go to him, and this was the last time I ever saw him. He came a part of the way back with me. We sat on a chestnut log and he told me that he felt like that we would never see each other again, and told me, also, where I would find his trunk and other belongings. He was killed at Lookout Mountain, Tennessee. I found his things, as he told me, his trunk and picture, but his girlfriend refused to part with his jewelry.

The first battle I engaged in was The Battle of Seven Pines. This battle took place along the Chickahominy River, and was as complete a victory as the Southern Army ever had. We drove twenty-seven miles down the river until we were under the shelter of their gunboats that lay in the James River. At this time our brigadier general was Maxcy Gregg of Florence, South Carolina, who was one of the bravest men I ever knew. Later I saw him, after he was killed, being carried on a stretcher at The Battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia. I do not know how old General Gregg was at the time of his death, but he looked to be about forty years old. From this time the battles were too numerous for me to remember the dates.

I fought in the following divisions: I fought under General A.P. Hill, General Maxcy Gregg, Abner Perrin. I was never wounded bad enough to leave the battlefield, but was knocked down by a ball at Vine Run, Virginia. I had a small camp Testament in my pocket which I think saved my life. The ball hit me in the region of my heart, doubling the Testament in the center. I was knocked down, was stunned, but soon got up and took my place in the battle.

At The Battle of Cold Harbor we fought all afternoon until dark. When the battle ceased, I was detailed to go to the rear and get water for the company. Taking as many canteens as I could carry, I went to a little ravine to get water. A Union soldier was lying near the ravine. His teeth had been shot out and his jawbone was broken. He made me understand that he wanted water. I held the canteen to his lips and he drank all he wanted. After this, he made me understand that he wanted me to carry him to the rear, as we were still in danger. I carried him about three hundred yards and left him. When I returned to my company, I was sent to help bring the dead. We worked all night until up into the next day.

I was in the Battle of Gettysburg, which lasted four days and nights. This was the most cruel of all the battles. It was a slaughter pen. I was a drummer boy at this time, and after three or four rounds of fighting, the bass drummer and I were detailed to care for the wounded. The Battle of the Wilderness was a thick forest of junipers which were hewn down by balls like a field of grain. It did not seem that a person could come out the battle alive.

Twice during the war I was dangerously ill. I had typhoid fever, also typhoid pneumonia. One day I was sent to Richmond, Virginia, a distance of about twelve miles, to drive cattle for beef for the army. On my way back to camp, a thundercloud arose, and I lay in a wet blanket that night in mud and water. When I awoke the next morning I was very sick. Two days later, my commander was sent to Fredericksburg, Virginia and I was sent to a hospital in Lynchburg, Virginia. I had developed typhoid fever. One Sunday morning while convalescing, two of us decided to ask permission of the doctor to let us take a walk. He agreed, on the condition that we would not eat anything on the trip. We promised. On our trip we saw a garden of beautiful green collards and asked a colored woman to cook some of them for us. This she did, and we ate all we wanted with no bad results.

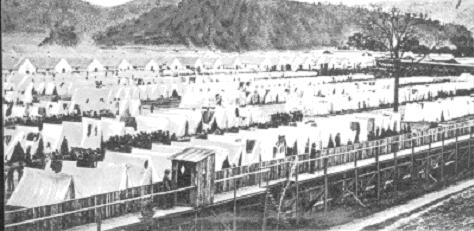

At Malvern Hill I was captured prisoner. From there was sent to Point Lookout, and from there was sent to Elmira, New York.

This was a very bitter experience. As it was very cold, the prisoners suffered severely from cold and hunger. Here, I contracted typhoid pneumonia and again, was dangerously ill. When I had about recovered, I got an exchange payroll. When I left prison they gave me a piece of pickled pork and hard tacks to eat. I would have died from hunger, but got up with some officers, who shared what they had with me.

I left Elmira, New York the 14th of March 1865, and reached my home on the 27th of March. I came home by way of Richmond, and came by railroad to Blackstock, South Carolina. The Union Army had torn up the railroad, and I had to walk the rest of the way, a distance of one hundred and ten miles. When my partner and I reached the Wateree River, we made an attempt to cross over without the help of the ferryman, and had a narrow escape from drowning. But the ferryman arrived and carried us safely over.

The first night after reaching Camden, I spent the night with a cousin who sent us a part of the way home the next morning. Sherman's Raid had passed through this country and had destroyed everything. "Life preserver peas" were about the only thing that could be had, and the people said that they had the right name.

On arriving home, I heard that my cousin, Edward Alexander, who served in the Western armies, who had been reported and lamented as dead for three years, had returned home two weeks previous. His funeral had been planned, and a preacher engaged to preach his funeral on the Sunday following his arrival on Friday night. On this Sunday, this soldier went to the service and told the preacher he need not bother about preaching his funeral.

I was in a company of one hundred and twelve men, and as far as I know, am the only living one at the present time. I was never wounded in the war, but soon after, I had the misfortune to get my leg broken twice in the same place. From this accident I have never recovered, but the results have followed me until the present time.

I am now in my 87th year. I have six children living, thirty-nine grandchildren, thirty-two great-grandchildren, and one great-great grandchild. I am also the only one of my family of the older Alexanders living now. (signed) John Wesley Alexander"

Obituary from "Florence Morning News", and believed to have written by John Alexander's daughter, Maggie Louise Alexander:

"Taps for Brave Soldier Sound

Funeral Services for John W. Alexander at Timmonsville Today

Special to Morning News:

TIMMONSVILLE, Feb 14 - Funeral services for John W. Alexander, 87, gallant Confederate veteran who died Tuesday night at his home a few miles from Timmonsville, will be held Thursday morning 11 o'clock from the Pine Grove Methodist church conducted by his pastor, the Rev. J.F. Campbell. Interment will follow in the Thornwell Cemetery (Thornal is correct) beside the grave of his wife.

Mr. Alexander enlisted in the Confederate army at the age of fifteen years and served throughout the war. He was a member of Culpepper Camp, U.C.V. of Timmonsville. For thirty years he had been superintendent of the Pine Grove Methodist Sunday School being assisted the last few years by his son Luther Alexander.

Mr. Alexander was a splendid Christian gentleman and his influence for good has been far reaching. His death, due to heart trouble from which he had been suffering for some time brings sorrow to a host of friends.

Surviving are two daughters, Mrs. George Hatchell and Miss Maggie Alexander and four sons; J.L., J.K., C.E. Alexander all the Timmonsville section, and H.L. Alexander of Greenville. He also leaves 32 grandchildren, 30 great-grandchildren and four 2-great-grandchildren. The passbearers will be six grandsons: Gary Hill, Roy Hatchell, Lee, Arnold, James, and Earl Alexander."

Obituary from the March 15, 1934 issue of the Methodist periodical "Southern Christian Advocate":

"On Feb 13, 1934, death came into our midst and removed from the home, church and Sunday school one of the most faithful and beloved members, Bro. John Wesley Alexander, 87 years 5 months and 17 days of age. He was the son of the late Rev. John William Alexander who died in the year 1903 (1899 is correct). His loving wife passed through the gate of death in 1917, leaving him a widower for the past 17 years.

Brother Alexander gave his heart to God around 45 years ago and had a rich experience until the day came when he fell asleep. He really did fall asleep. On Friday night preceding his death, realizing that he was soon to pass out, he called all who were near to his bedside and talked and prayed with them closing with a benediction. He then went into a state of coma and breathed his last on the following Tuesday night. He served as steward of Pine Grove Methodist Church for quite a number of years and was superintendent of the Sunday school until the day of his death. He died in harness for his Lord.

He was a member of the league of Confederacy, having served all four years in the war between the States. During the war his life was saved by a pocket Testament. A bullet, which perhaps would have pierced his heart, struck the Testament in his pocket and his life was spared.

He is survived by six children: Charlie Alexander, H.L. Alexander, J. Luther Alexander, Joseph Alexander, Mrs. G.C. Hatchell, and Miss Maggie Alexander; also 40 grandchildren, 40 great grandchildren, and 3 great great grandchildren. He is gone but not forgotten. His works do follow him. - J.F. Campbell"

John and his wife Sallie had another daughter, Ella L. Alexander Hatchell, not listed, who died in the early 1900s at age 33. Although it is theorized that she was buried in John's "Lone Tree Farm" family cemetery, not too far from Pine Grove, it has not been proven that she is buried there. There has been a lot of destruction there over the years.

Family Members

-

![]()

Mary Elizabeth "Mary" Alexander Rogers

1867–1886

-

![]()

Charles Engram "Charlie" Alexander

1871–1949

-

![]()

Henry Lee Alexander

1872–1948

-

![]()

Mattie Viola Alexander Hatchell

1874–1951

-

![]()

John Luther Alexander Sr

1878–1955

-

![]()

Maggie Louise Alexander

1879–1965

-

![]()

Addie Olivia Alexander Hill

1883–1911

-

![]()

Joseph Kirkland "Joe" Alexander Sr

1885–1962

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

Advertisement