Roy is the only American casualty from the Great War whose body remains on the Scottish island of Islay.

He was born in Rico, Colorado, the son of William J. Muncaster (born in England 18th October 1853) and Elizabeth Muncaster( born in England 11th March 1853)and at the time of enlistment worked as a forest ranger in Seattle, Washington State.

His siblings were:

John, William and James.

Elizabeth, Edith and Ethyl(sic.)

All the Tuscania soldiers were exhumed with the exception of one man. The family of Private Roy Muncaster requested that his body remain undisturbed.

The good folks of Islay ensured that his grave would be attended to as if he were one of their own. It is now maintained by The Commonwealth War Graves Commission-quite unique as they do not care for private memorials, nor do they usually maintain the graves of non-Commonwealth casualties.

Muncaster Mountain in Quinault, Washington is named in his memory.

Address: 4503 17th Ave. N.E., Seattle, WA 98105 (1917)

University of Washington Graduate; Degree in Forestry

Member of Phi Gamma Delta Fraternity, Sigma Tau Chapter

University of Washington ROTC Cadet, Rank Private (6 months)

Forest Ranger for Quinault District, Olympic National Forest

The Great War came to an end when Germany surrendered November 11, 1918. Two years later in the summer of 1920 the American Red Cross financed the construction of a Monument to be built on the Island of Islay. The Monument stands in the shape of a Light House high above the cliffs where so many were lost in the wrecks of the Troop Transport Tuscania and the Otranto.

Also in 1920 a project began to exhume all the American Soldiers from their graves on Islay and relocate them to either Brookwood War Cemetery in England, or return them to the States.

Wisconsin Newspaper article (paper unknown)

June 30th, 1920

BODIES OF TUSCANIA VICTIMS TO BE EXHUMED AND RETURNED TO U.S.

PARIS - Exhumation of the bodies of 489 American soldiers which were washed upon the rocky shores of the Island of Islay off the Scottish Coast after the sinking of the transports Tuscania and Otranto in 1918, will be started July 1st 1920 it was announced here today.

The Scottish Clan which inhabits the lonely spot has taken tender care of the graves and the chief has given a pledge that the Clan would look after the graves as if they were its own, until the end of time. The Chief pleaded that the bodies be left on the Island, but relatives in many cases wished the return of the bodies and it was decided by the Graves Registration Service to remove them all.The coast of Islay is so steep and rocky that the coffins will have to be carried down steep trails cut in the rocks or lowered by ropes and tackle to a waiting barge, which will convey them to a Transport standing off shore.

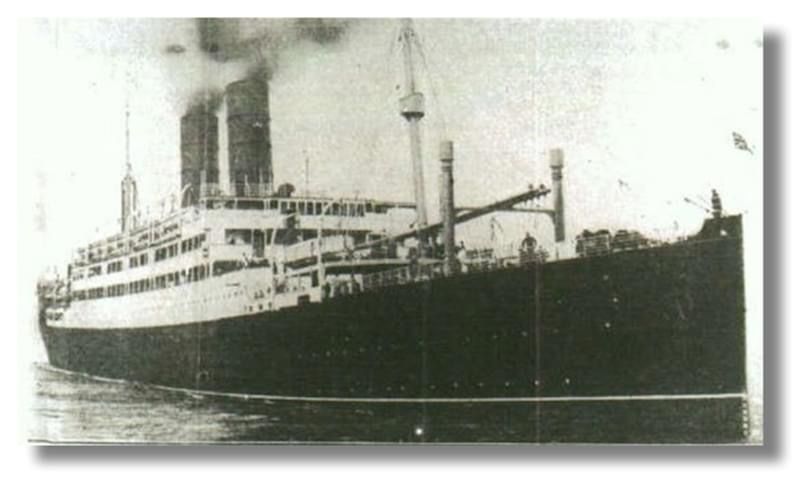

It seems that he was one of the heroes of this tragedy and that he saved others that they might live, sacrificing his own chance of survival. Greater love hath no man than this, that he lays down his life for his friends.The Tuscania was the first ship taking American troops to Europe to be torpedoed and sunk by a German submarine in the First World War. The ship was completed in 1914. Built originally for the Anchor line, it would be their largest and finest ship. By early 1916 the Tuscania was requisitioned by the British Admiralty and placed in the Cunard fleet for war service. On the final voyage the Tuscania was transporting U.S. Army troops to Europe. The troops that were aboard were as follows:1) 6th Battalion, 20th Forestry Engineers, Company D, E, F, and H.q. Division. 2) Aero squadrons of the 100th, 158th, and 213th U.S. Army Air Corps. 3) Advanced Elements of the 32nd Division National Guard from Wisconsin and Michigan. 4) Officers and replacement troops from Camp Travis, Texas. 7 December 1917, The formation of the 6th Battalion, 20th Engineers was ordered to be organized. The formation began at Ft. Meyer, Va. The War Department made the rapid formation of forestry troops one of its primary objectives to the American Expeditionary Forces. The troops were dependent on lumber.The Forestry troops would supply lumber for dugouts, trenches, entanglements. They would construct compounds for prisoners, and construct all the Military facilities that were required. December 1917, Two hundred and forty nine recruits composed the 6th Battalion 20th Engineers at this time. Some were hospital cases left over from other battalions. 27 December 1917, The 6th Battalion moves to Camp American University, Washington, DC (Regimental Headquarters) were they were organized, and trained. (Col. W. A.Mitchell, Regimental Commanding Officer) 25% forestry experts, 25% officers with Military training, 50% Sawmill and Logging men, made up the 6th Battalion Forestry Engineers. 1 January 1918, With the arrival of several hundred men from the Pacific Northwest, and the Great Lakes region, the 6th Battalion reached war strength (750 Men). Training and organizing continues. 22 January 1918, At 9:30 p.m., under full pack the 6th Battalion moves out of Camp American University, on a hike of five and half miles through the snow, to Ft. Meyer, where the Sixth Battalion boards a train at midnight for Hoboken, New Jersey, reaching the port at noon the next day. 23 January 1918, 6th Battalion, 20th Engineers ( 750 men ) companies D, E, F, plus medical and H.q. ( 35 men ),together with several Aerial Squadrons and a few miscellaneous troops, 2,300 men in all, went on board the troopship "Tuscania". She was manned by British officers and crew. While in port the Tuscania was painted an olive drab for camouflage. A special Rapid fire four inch gun was mounted at her stern. 24 January 1918, Tuscania is scheduled to embark from pier 56, destination Le Havre, France.(scheduled arrival date, March 24, 1918) The Tuscania is to stop in Halifax, and Britain,before reaching her final destination. The ship steams for Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. On the morning of 26 January 1918, the SS Tuscania arrives in Halifax, the designated rendezvous, for this ship, joining ships from other locations, to form a convoy. Sunday,January 1918, SS Tuscania leaves the harbour of Halifax with 2 other troopships, HMS Baltic and HMS Ceramic. The troops on the Baltic are mainly Canadian, and a few Americans. Joining these ships is the USS Kanawha (oil tanker with U.S.Navy personnel), Tunisian (cargo), Oanfa (cargo), Scotian (cattle boat), Dwisk (cattle boat), Westmoreland (merchant ship), Orita (merchant ship), and the Kursk (merchant ship). Escorting the convoy are 9 HMS Class British Cruiser Destroyers. The lead escort is the HMS Cochrane.Protecting the sides of the convoy are the Minos, Harpy, Beagle, Savage,Grasshopper, Badger, Pigeon, and HMS Mosquito. Positioned far in front of the Tuscania is the Baltic, while behind her is the USS Kanawha. On the Tuscania's starboard side is the Oanfa, and on the port side is the Scotian. A zig-zag course was followed on the voyage, and great precautions were taken especially at night. A boat drill was performed every day at 2:00 p.m. By the time the convoy was 2 days out of Halifax,the soldiers knew their proper lifeboat stations. They were informed that in an emergency, the ship's officer and 6 of the ship's crew were trained in the operations of emergency evacuation and would be at each of the stations to lower the boats. 4 February 1918, twelve days at sea, while west of Ireland, the convoy is met by 8 British destroyers that came to escort them through the British Isles.5 February 1918, German U-boat 77 (submarine) had come north after operating off Berehaven to try her luck in the North Channel, and in spite of being hampered by destroyers as well as other patrols, took up her position seven miles north of Rathlin Island Lighthouse, in which UB-97 happened to be operating. The convoy had passed the Northern tip of Ireland, and was proceeding South Easterly of Ireland in the North English Channel. It is recorded that they are 30 miles from land, the Scottish Coast on one side, the Irish Coast on the opposite side.4:30 p.m. The two submarines meet and exchange remarks, UB 97 leaves. 5:05 p.m. UB - 77 sighted a convoy eastward bound strongly guarded by destroyers, speed twelve knots. Lieut.-Commander Wilhelm Meyer of Saarbrucken, Germany is in command. An able officer, he is determined to get in his attack before the light of day has departed. 5:40 p.m With considerable difficulty Commander Meyer fires two torpedoes (G7 type II, 280 kg. warhead) at what he perceived as the largest ship of this convoy, the Tuscania, range 1300 yards. No alarm sounded from any one of the 15 lookouts on the Tuscania. No one saw the wake of foam as the torpedo came towards the vessel. 5:41 p.m. One torpedo passes harmlessly in front of the Tuscania. The second torpedo slams into the side of the Tuscania's hull. Simultaneously the lights went out and a deafening crash echoed and re-echoed through the ship. The torpedo struck squarely amidships on the starboard side (boiler room).A great hole was torn in the hull and all the superstructure directly above was reduced to a mass of wreckage. Several lifeboats were lost due to the explosion, which had thrown a sheet of flame and debris, two hundred feet in the air. Fragments of steel and wood, were shot in all directions. Clouds of hissing steam rose from the ship.From the moment of the explosion the ship began listing starboard. 5 February 1918-the men went into action scrambling to their posts. The ship's crew was almost non-existent as far as help was concerned. The ship's officers were engaged in other duties for some time, starting the emergency dynamo, sending up flare rockets etc.1st Lieut. Donald A. Smith notes, "Our men had to lower the boats, they made an awful mess of it. I saw one boat containing about 25 men, dropped nearly thirty feet flat onto a crowded boat in the water. I saw another boat dropped perpendicular, spilling the 25 or more occupants out, into the water like a sack of beans, then down went the boat, stern first, among them. This type of accident happened several times. At least half of our loss, must have been due to men being crushed by falling lifeboats. Some of the men in the water were crushed between the lifeboats and the liner. "The waves of the sea were high and the darkness made the rescue of men in the water almost impossible. They worked feverishly to lower the lifeboats. Private Roy Muncaster from Washington, and Sergeant Everett Harpham, a native Oregonian, worked for an hour, along with several others, at the pulleys and the tangled cables, getting the lifeboats launched into the foaming, pounding sea. The pitch darkness made the work more difficult. Our soldiers were not trained in the procedures of lowering lifeboats. Yet now, their ship was sinking. They had no idea how the davits had to be managed to get a boat safely into the water. The work on lowering the lifeboats proved discouraging. The boat tackle was discovered, in many cases, to have been fouled or rotted and unfit for use. The Tuscania acquired such a list to the starboard side, it was necessary on the port side to slide the lifeboats down the rivet-studded sloping side of the ship with the aid of oars as levers. In all some 30 lifeboats were launched and perhaps 12 of these were successful. 6:55 p.m. Muncaster and Harpham slid down the ropes into the last lifeboat. The lifeboats were tossed about in the relentless pounding of the sea. The men stood in icy water up to their knees, some dipping and bailing constantly to keep afloat. George Schwartz (6th Battalion, 20th Engineers, F company) from Richmond, Michigan, wrote later "We got into a life boat which was half swamped. Was washed off the life boat twice but managed to crawl back on. My legs were soon chilled by the icy water, sitting in the boat which was full of water so that I could not move them but held on with my hands. The life boat was partially submerged in the water for over 4 hours". 5 February 1918 7:00 p.m.. On the Tuscania all the lifeboats gone 1350 men still aboard, excitement filled the air as they felt helplessly trapped. It was not certain how fast the Tuscania was sinking. Out of the darkness, a tiny destroyer came siding up to the troopship. She approached near enough for men to be transferred to her deck. UB-77 fires a torpedo from the stern tube (K type III) at this destroyer, which misses; another destroyer starts dropping depth charges. When the destroyer was loaded to her limit, she steamed away. 7:00 p.m. 1st Lieut. Donald A. Smith saw a smashed in, collapsible boat floating away past the stern. With two enlisted men following him, they slid down the ropes and swam for the boat. 1st Lieut. Smith remembers,"We shivered in that boat for five hours because we didn't know how to light the flares in the boat. I found them right away, they were under water and I wasted a dozen trying to light one. We were fast approaching the rocks of Islay Island. I made a thorough search for the matches, I knew they were somewhere. I found them in a lantern, in a tin box. I didn't know the secret in opening it. I was quite frustrated. It took me twenty minutes to cut it open, because I couldn't find the opening in the dark and cold. With a match I read the flare directions, which told me they were to be scratched, not lighted". 5 February 1918 A soldier writes "The lifeboats and rafts were drifting helplessly about, it was impossible to make any headway with the oars, as most of the boats were full of water, and there was such a heavy sea, that any such effort was useless. In and out among these boats the destroyers raced, looking for traces of the submarine and dropping depth bombs where there were any suspicious indications. Each time one of the "ash cans", exploded, the boats would shiver and shake with concussion. Those men who were in the water were knocked breathless with each explosion, and in a few cases rendered unconscious. The noise of the depth bombs, the bursting of the distress and the illuminating rockets, together with the reports from the destroyer's deck guns, created the impression that a Naval battle was in progress. Most of the boys believed we were being shelled by the Germans. 5 February 1918 8:15 p.m. A second destroyer sided up to the Tuscania and completed the rescue work. She was crowded to the limit but stayed till every known person on board was transferred. No sooner had she pulled away, the longitudinal bulkheads gave way, admitting the water to the port holds. Slowly the Tuscania resumed an even keel. The waves were pounding fiercely against the rocky shoal of Islay Island, a lifeboat carrying 20 men shatters on the rocks, Sergeant Harpham and Private Muncaster are aboard. An undertow pulled Harpham under the surface. His head struck a rock, leaving him stunned. A huge wave threw him high on a sharp rock. Another wave brought him onto a higher rock. From here he managed to crawl to a larger rock that gave him some protection from the waves, and the bitter wind, which now seemed to freeze the blood in his body. Finally, five of his companions joined him, and they huddled together on this large rock. They would be rescued 4 or 5 hours later. This never - forgotten night was filled with pitiful and anguished cries of men calling for help along the shore. Battered by the waves and smashing rocks, Private Muncaster and 12 of his lifeboat companions, floated motionless in the pounding tide. Out of the 20 in that particular lifeboat, only 8 survived. A number of trawlers and small fishing boats helped in gathering survivors. These vessels together with the destroyers combed the vicinity picking up men in lifeboats and rafts. Each bit of wreckage was closely scanned for the possibility that someone may be clinging to it. In this way the majority of the living were rescued. Darkness and the wide area over which the rafts and boats were scattered made it impossible to find them all. 10:00 p.m. Four hours after being struck, the Tuscania took her final plunge. With a muffled explosion as the water reached her boilers, she gently slid, bow first, under the surface. According to official reports from the British Navy the Tuscania sank 7 miles north of the Rathlin Ireland Lighthouse. Latitude 55 degrees, 25 minutes north ; Longitude 6 degrees, 13 minutes west. However the Tuscania did not sink at that location. The U-boat had intercepted the distress signals, and thought it was odd that the distress signal was reporting the ship sinking in the wrong location. 10:00 p.m. Somewhere near the rocky coast of Islay Island. 1st Lieut. Donald Smith recalls "I had the pleasure of seeing several people picked up near me but was unable to attract their attention." 5 February 1918 Between 10:30 to 11:00 p.m. George Schwartz had a fracture to the skull, and was very ill. In a semi-conscious condition George and the men in his raft are rescued by the British Trawler "Elf King". While on board the destroyer George took a blow on the head owing to the excessive motion of the boat. He was taken to a hospital in Larne, Ireland. 12:00 Midnight, 1st Lieut. Donald Smith and his two companions are picked up by a trawler.

ON ENSANGUINED FIELDS OF HONOR

Three golden stars are upon Sigma Tau's World War I service flag. They are for Adelbert McCleverty 1912; J. Roy Muncaster 1917, and Harold Clarence White 1920.

Roy is the only American casualty from the Great War whose body remains on the Scottish island of Islay.

He was born in Rico, Colorado, the son of William J. Muncaster (born in England 18th October 1853) and Elizabeth Muncaster( born in England 11th March 1853)and at the time of enlistment worked as a forest ranger in Seattle, Washington State.

His siblings were:

John, William and James.

Elizabeth, Edith and Ethyl(sic.)

All the Tuscania soldiers were exhumed with the exception of one man. The family of Private Roy Muncaster requested that his body remain undisturbed.

The good folks of Islay ensured that his grave would be attended to as if he were one of their own. It is now maintained by The Commonwealth War Graves Commission-quite unique as they do not care for private memorials, nor do they usually maintain the graves of non-Commonwealth casualties.

Muncaster Mountain in Quinault, Washington is named in his memory.

Address: 4503 17th Ave. N.E., Seattle, WA 98105 (1917)

University of Washington Graduate; Degree in Forestry

Member of Phi Gamma Delta Fraternity, Sigma Tau Chapter

University of Washington ROTC Cadet, Rank Private (6 months)

Forest Ranger for Quinault District, Olympic National Forest

The Great War came to an end when Germany surrendered November 11, 1918. Two years later in the summer of 1920 the American Red Cross financed the construction of a Monument to be built on the Island of Islay. The Monument stands in the shape of a Light House high above the cliffs where so many were lost in the wrecks of the Troop Transport Tuscania and the Otranto.

Also in 1920 a project began to exhume all the American Soldiers from their graves on Islay and relocate them to either Brookwood War Cemetery in England, or return them to the States.

Wisconsin Newspaper article (paper unknown)

June 30th, 1920

BODIES OF TUSCANIA VICTIMS TO BE EXHUMED AND RETURNED TO U.S.

PARIS - Exhumation of the bodies of 489 American soldiers which were washed upon the rocky shores of the Island of Islay off the Scottish Coast after the sinking of the transports Tuscania and Otranto in 1918, will be started July 1st 1920 it was announced here today.

The Scottish Clan which inhabits the lonely spot has taken tender care of the graves and the chief has given a pledge that the Clan would look after the graves as if they were its own, until the end of time. The Chief pleaded that the bodies be left on the Island, but relatives in many cases wished the return of the bodies and it was decided by the Graves Registration Service to remove them all.The coast of Islay is so steep and rocky that the coffins will have to be carried down steep trails cut in the rocks or lowered by ropes and tackle to a waiting barge, which will convey them to a Transport standing off shore.

It seems that he was one of the heroes of this tragedy and that he saved others that they might live, sacrificing his own chance of survival. Greater love hath no man than this, that he lays down his life for his friends.The Tuscania was the first ship taking American troops to Europe to be torpedoed and sunk by a German submarine in the First World War. The ship was completed in 1914. Built originally for the Anchor line, it would be their largest and finest ship. By early 1916 the Tuscania was requisitioned by the British Admiralty and placed in the Cunard fleet for war service. On the final voyage the Tuscania was transporting U.S. Army troops to Europe. The troops that were aboard were as follows:1) 6th Battalion, 20th Forestry Engineers, Company D, E, F, and H.q. Division. 2) Aero squadrons of the 100th, 158th, and 213th U.S. Army Air Corps. 3) Advanced Elements of the 32nd Division National Guard from Wisconsin and Michigan. 4) Officers and replacement troops from Camp Travis, Texas. 7 December 1917, The formation of the 6th Battalion, 20th Engineers was ordered to be organized. The formation began at Ft. Meyer, Va. The War Department made the rapid formation of forestry troops one of its primary objectives to the American Expeditionary Forces. The troops were dependent on lumber.The Forestry troops would supply lumber for dugouts, trenches, entanglements. They would construct compounds for prisoners, and construct all the Military facilities that were required. December 1917, Two hundred and forty nine recruits composed the 6th Battalion 20th Engineers at this time. Some were hospital cases left over from other battalions. 27 December 1917, The 6th Battalion moves to Camp American University, Washington, DC (Regimental Headquarters) were they were organized, and trained. (Col. W. A.Mitchell, Regimental Commanding Officer) 25% forestry experts, 25% officers with Military training, 50% Sawmill and Logging men, made up the 6th Battalion Forestry Engineers. 1 January 1918, With the arrival of several hundred men from the Pacific Northwest, and the Great Lakes region, the 6th Battalion reached war strength (750 Men). Training and organizing continues. 22 January 1918, At 9:30 p.m., under full pack the 6th Battalion moves out of Camp American University, on a hike of five and half miles through the snow, to Ft. Meyer, where the Sixth Battalion boards a train at midnight for Hoboken, New Jersey, reaching the port at noon the next day. 23 January 1918, 6th Battalion, 20th Engineers ( 750 men ) companies D, E, F, plus medical and H.q. ( 35 men ),together with several Aerial Squadrons and a few miscellaneous troops, 2,300 men in all, went on board the troopship "Tuscania". She was manned by British officers and crew. While in port the Tuscania was painted an olive drab for camouflage. A special Rapid fire four inch gun was mounted at her stern. 24 January 1918, Tuscania is scheduled to embark from pier 56, destination Le Havre, France.(scheduled arrival date, March 24, 1918) The Tuscania is to stop in Halifax, and Britain,before reaching her final destination. The ship steams for Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. On the morning of 26 January 1918, the SS Tuscania arrives in Halifax, the designated rendezvous, for this ship, joining ships from other locations, to form a convoy. Sunday,January 1918, SS Tuscania leaves the harbour of Halifax with 2 other troopships, HMS Baltic and HMS Ceramic. The troops on the Baltic are mainly Canadian, and a few Americans. Joining these ships is the USS Kanawha (oil tanker with U.S.Navy personnel), Tunisian (cargo), Oanfa (cargo), Scotian (cattle boat), Dwisk (cattle boat), Westmoreland (merchant ship), Orita (merchant ship), and the Kursk (merchant ship). Escorting the convoy are 9 HMS Class British Cruiser Destroyers. The lead escort is the HMS Cochrane.Protecting the sides of the convoy are the Minos, Harpy, Beagle, Savage,Grasshopper, Badger, Pigeon, and HMS Mosquito. Positioned far in front of the Tuscania is the Baltic, while behind her is the USS Kanawha. On the Tuscania's starboard side is the Oanfa, and on the port side is the Scotian. A zig-zag course was followed on the voyage, and great precautions were taken especially at night. A boat drill was performed every day at 2:00 p.m. By the time the convoy was 2 days out of Halifax,the soldiers knew their proper lifeboat stations. They were informed that in an emergency, the ship's officer and 6 of the ship's crew were trained in the operations of emergency evacuation and would be at each of the stations to lower the boats. 4 February 1918, twelve days at sea, while west of Ireland, the convoy is met by 8 British destroyers that came to escort them through the British Isles.5 February 1918, German U-boat 77 (submarine) had come north after operating off Berehaven to try her luck in the North Channel, and in spite of being hampered by destroyers as well as other patrols, took up her position seven miles north of Rathlin Island Lighthouse, in which UB-97 happened to be operating. The convoy had passed the Northern tip of Ireland, and was proceeding South Easterly of Ireland in the North English Channel. It is recorded that they are 30 miles from land, the Scottish Coast on one side, the Irish Coast on the opposite side.4:30 p.m. The two submarines meet and exchange remarks, UB 97 leaves. 5:05 p.m. UB - 77 sighted a convoy eastward bound strongly guarded by destroyers, speed twelve knots. Lieut.-Commander Wilhelm Meyer of Saarbrucken, Germany is in command. An able officer, he is determined to get in his attack before the light of day has departed. 5:40 p.m With considerable difficulty Commander Meyer fires two torpedoes (G7 type II, 280 kg. warhead) at what he perceived as the largest ship of this convoy, the Tuscania, range 1300 yards. No alarm sounded from any one of the 15 lookouts on the Tuscania. No one saw the wake of foam as the torpedo came towards the vessel. 5:41 p.m. One torpedo passes harmlessly in front of the Tuscania. The second torpedo slams into the side of the Tuscania's hull. Simultaneously the lights went out and a deafening crash echoed and re-echoed through the ship. The torpedo struck squarely amidships on the starboard side (boiler room).A great hole was torn in the hull and all the superstructure directly above was reduced to a mass of wreckage. Several lifeboats were lost due to the explosion, which had thrown a sheet of flame and debris, two hundred feet in the air. Fragments of steel and wood, were shot in all directions. Clouds of hissing steam rose from the ship.From the moment of the explosion the ship began listing starboard. 5 February 1918-the men went into action scrambling to their posts. The ship's crew was almost non-existent as far as help was concerned. The ship's officers were engaged in other duties for some time, starting the emergency dynamo, sending up flare rockets etc.1st Lieut. Donald A. Smith notes, "Our men had to lower the boats, they made an awful mess of it. I saw one boat containing about 25 men, dropped nearly thirty feet flat onto a crowded boat in the water. I saw another boat dropped perpendicular, spilling the 25 or more occupants out, into the water like a sack of beans, then down went the boat, stern first, among them. This type of accident happened several times. At least half of our loss, must have been due to men being crushed by falling lifeboats. Some of the men in the water were crushed between the lifeboats and the liner. "The waves of the sea were high and the darkness made the rescue of men in the water almost impossible. They worked feverishly to lower the lifeboats. Private Roy Muncaster from Washington, and Sergeant Everett Harpham, a native Oregonian, worked for an hour, along with several others, at the pulleys and the tangled cables, getting the lifeboats launched into the foaming, pounding sea. The pitch darkness made the work more difficult. Our soldiers were not trained in the procedures of lowering lifeboats. Yet now, their ship was sinking. They had no idea how the davits had to be managed to get a boat safely into the water. The work on lowering the lifeboats proved discouraging. The boat tackle was discovered, in many cases, to have been fouled or rotted and unfit for use. The Tuscania acquired such a list to the starboard side, it was necessary on the port side to slide the lifeboats down the rivet-studded sloping side of the ship with the aid of oars as levers. In all some 30 lifeboats were launched and perhaps 12 of these were successful. 6:55 p.m. Muncaster and Harpham slid down the ropes into the last lifeboat. The lifeboats were tossed about in the relentless pounding of the sea. The men stood in icy water up to their knees, some dipping and bailing constantly to keep afloat. George Schwartz (6th Battalion, 20th Engineers, F company) from Richmond, Michigan, wrote later "We got into a life boat which was half swamped. Was washed off the life boat twice but managed to crawl back on. My legs were soon chilled by the icy water, sitting in the boat which was full of water so that I could not move them but held on with my hands. The life boat was partially submerged in the water for over 4 hours". 5 February 1918 7:00 p.m.. On the Tuscania all the lifeboats gone 1350 men still aboard, excitement filled the air as they felt helplessly trapped. It was not certain how fast the Tuscania was sinking. Out of the darkness, a tiny destroyer came siding up to the troopship. She approached near enough for men to be transferred to her deck. UB-77 fires a torpedo from the stern tube (K type III) at this destroyer, which misses; another destroyer starts dropping depth charges. When the destroyer was loaded to her limit, she steamed away. 7:00 p.m. 1st Lieut. Donald A. Smith saw a smashed in, collapsible boat floating away past the stern. With two enlisted men following him, they slid down the ropes and swam for the boat. 1st Lieut. Smith remembers,"We shivered in that boat for five hours because we didn't know how to light the flares in the boat. I found them right away, they were under water and I wasted a dozen trying to light one. We were fast approaching the rocks of Islay Island. I made a thorough search for the matches, I knew they were somewhere. I found them in a lantern, in a tin box. I didn't know the secret in opening it. I was quite frustrated. It took me twenty minutes to cut it open, because I couldn't find the opening in the dark and cold. With a match I read the flare directions, which told me they were to be scratched, not lighted". 5 February 1918 A soldier writes "The lifeboats and rafts were drifting helplessly about, it was impossible to make any headway with the oars, as most of the boats were full of water, and there was such a heavy sea, that any such effort was useless. In and out among these boats the destroyers raced, looking for traces of the submarine and dropping depth bombs where there were any suspicious indications. Each time one of the "ash cans", exploded, the boats would shiver and shake with concussion. Those men who were in the water were knocked breathless with each explosion, and in a few cases rendered unconscious. The noise of the depth bombs, the bursting of the distress and the illuminating rockets, together with the reports from the destroyer's deck guns, created the impression that a Naval battle was in progress. Most of the boys believed we were being shelled by the Germans. 5 February 1918 8:15 p.m. A second destroyer sided up to the Tuscania and completed the rescue work. She was crowded to the limit but stayed till every known person on board was transferred. No sooner had she pulled away, the longitudinal bulkheads gave way, admitting the water to the port holds. Slowly the Tuscania resumed an even keel. The waves were pounding fiercely against the rocky shoal of Islay Island, a lifeboat carrying 20 men shatters on the rocks, Sergeant Harpham and Private Muncaster are aboard. An undertow pulled Harpham under the surface. His head struck a rock, leaving him stunned. A huge wave threw him high on a sharp rock. Another wave brought him onto a higher rock. From here he managed to crawl to a larger rock that gave him some protection from the waves, and the bitter wind, which now seemed to freeze the blood in his body. Finally, five of his companions joined him, and they huddled together on this large rock. They would be rescued 4 or 5 hours later. This never - forgotten night was filled with pitiful and anguished cries of men calling for help along the shore. Battered by the waves and smashing rocks, Private Muncaster and 12 of his lifeboat companions, floated motionless in the pounding tide. Out of the 20 in that particular lifeboat, only 8 survived. A number of trawlers and small fishing boats helped in gathering survivors. These vessels together with the destroyers combed the vicinity picking up men in lifeboats and rafts. Each bit of wreckage was closely scanned for the possibility that someone may be clinging to it. In this way the majority of the living were rescued. Darkness and the wide area over which the rafts and boats were scattered made it impossible to find them all. 10:00 p.m. Four hours after being struck, the Tuscania took her final plunge. With a muffled explosion as the water reached her boilers, she gently slid, bow first, under the surface. According to official reports from the British Navy the Tuscania sank 7 miles north of the Rathlin Ireland Lighthouse. Latitude 55 degrees, 25 minutes north ; Longitude 6 degrees, 13 minutes west. However the Tuscania did not sink at that location. The U-boat had intercepted the distress signals, and thought it was odd that the distress signal was reporting the ship sinking in the wrong location. 10:00 p.m. Somewhere near the rocky coast of Islay Island. 1st Lieut. Donald Smith recalls "I had the pleasure of seeing several people picked up near me but was unable to attract their attention." 5 February 1918 Between 10:30 to 11:00 p.m. George Schwartz had a fracture to the skull, and was very ill. In a semi-conscious condition George and the men in his raft are rescued by the British Trawler "Elf King". While on board the destroyer George took a blow on the head owing to the excessive motion of the boat. He was taken to a hospital in Larne, Ireland. 12:00 Midnight, 1st Lieut. Donald Smith and his two companions are picked up by a trawler.

ON ENSANGUINED FIELDS OF HONOR

Three golden stars are upon Sigma Tau's World War I service flag. They are for Adelbert McCleverty 1912; J. Roy Muncaster 1917, and Harold Clarence White 1920.

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement