At age 21, Norman married on 4 March 1896 to Lulu Pearl Miles (1876-1898); but she died on March 3rd, and was buried on March 4th, on what would have been their second wedding anniversary. Wishing to make a fresh start, Norman left Butler in 1898, and bicycled from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to St. Louis, Missouri. He worked there a short while to save money for a train ticket to San Francisco, where he obtained employment at a mill on the waterfront.

Later he went to work in the big mill at Santa Clara, and studied architecture at night by correspondence courses. He became a draftsman with Bliss & Faville, San Francisco architects, and soon was head of their drafting department. After the 1906 earthquake, he worked with them rebuilding the St. Francis Hotel, which had been gutted by the fire, and also the St. Francis hospital.

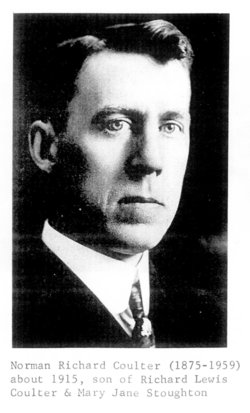

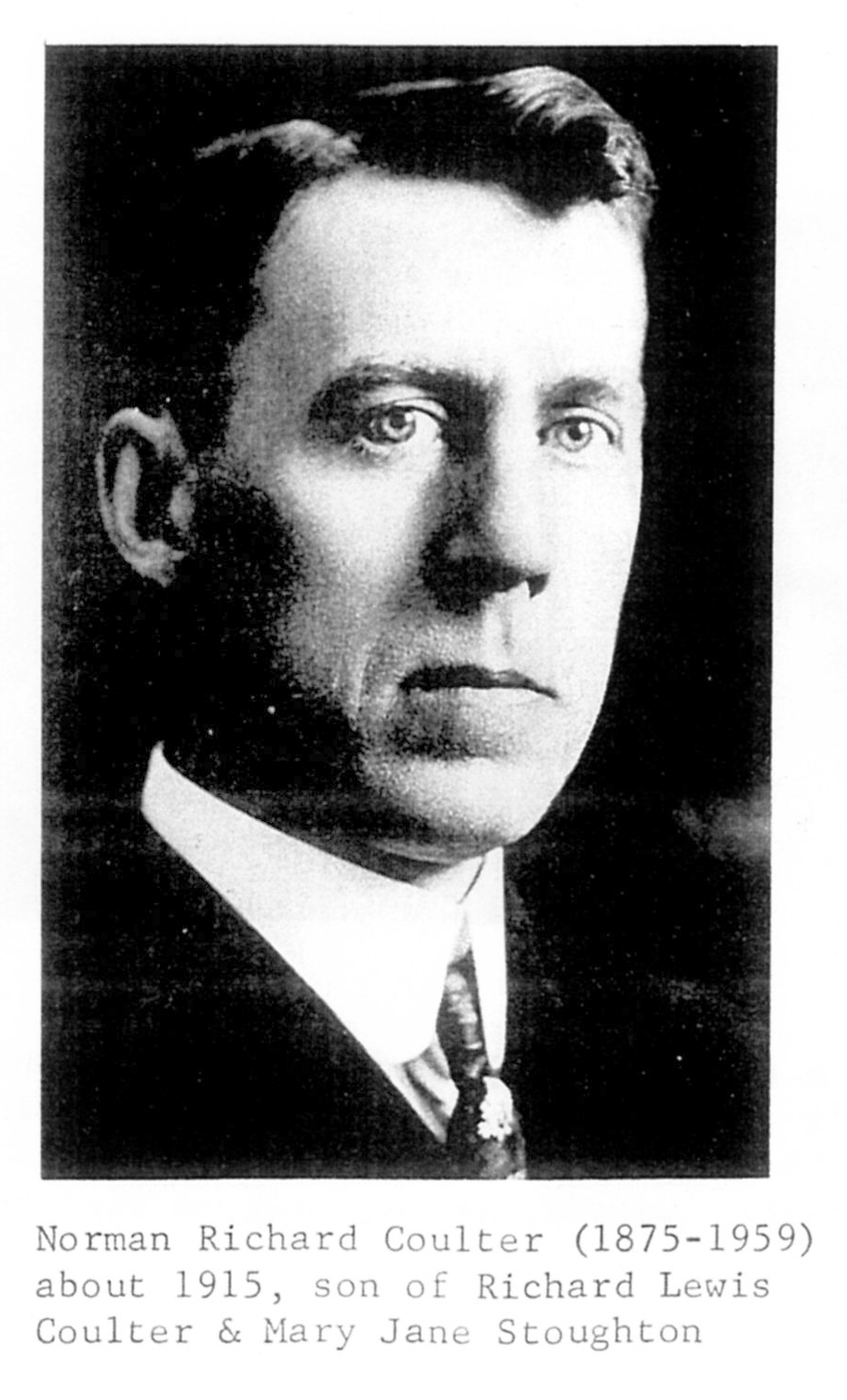

Norman took the California state exam and became a licensed architect. He specialized in designing large public schools in northern and central California. He also built hotels, theatres, jails, the John Deere building---a "first" in design, necessitating the city pass a new building ordinance; and the Colonel Andrews Jewelry store in San Francisco---then one of the most beautiful buildings in the world, with murals by E. Tojetti, a Vatican muralist. The Portuguese government commissioned Norman to set up their ornate building at the 1915 Pan-American International Exposition in San Francisco. When World War I started, Norman drew up the first complete set of plans for a United States Navy destroyer. When Norman registered for the military draft on 12 September 1918, he was six feet tall, blue eyes, black hair, age 43, occupation: ship draftsman for Bethlehem Ship Builders, 20th Illinois Street, San Francisco; residence: 146-21st Street, San Francisco; spouse: Winifred King Coulter (the war ended two months later on 11 November 1918).

On a trip to Los Angeles in the 1920s, Norman was almost waylaid by a group of highwaymen; but he became suspicious and managed to elude them. As soon as he reached the nearest town, he contacted the sheriff of Santa Barbara and helped capture the gang, which had been terrorizing travelers for some time. Sheriff Ross appointed Norman a deputy sheriff, as did the sheriffs of Del Norte County and San Francisco County.

In the 1930s, Norman owned Big Tree Park, a resort lodge surrounded by giant redwoods at Requa, California. Norman was an expert photographer, and developed his own pictures. He used his photos of his redwoods on personally-designed Christmas cards promoting his resort. But thanks to the Great Depression, Big Tree Park failed; and Norman lost everything.

His personal life also included disappointments. Norman had a fine singing voice; and he and his second wife Caroline performed in church recitals. They wed on 2 July 1901, but the marriage ended in divorce; and Caroline took their two children: Therese and Richard with her to her father's home in San Jose, California. Young Richard---named after his grandfather---died at age 38 in 1943. Richard was childless; so the Coulter name is extinct on this branch of our family tree. (Norman's older brother James was also childless.)

Norman had no children by his third marriage, on 17 Aug 1916, to Winifred Cliff King (1880-1930), or his fourth, to Lillian Martha Arland (1902-1987), a native of Canada, who was the same age as Norman's only daughter, Therese. Lillian was Norman's photography assistant, both before and after their marriage. (Being an astute Coulter, Norman probably realized he would no longer have to pay Lillian an employee's salary after they married!)

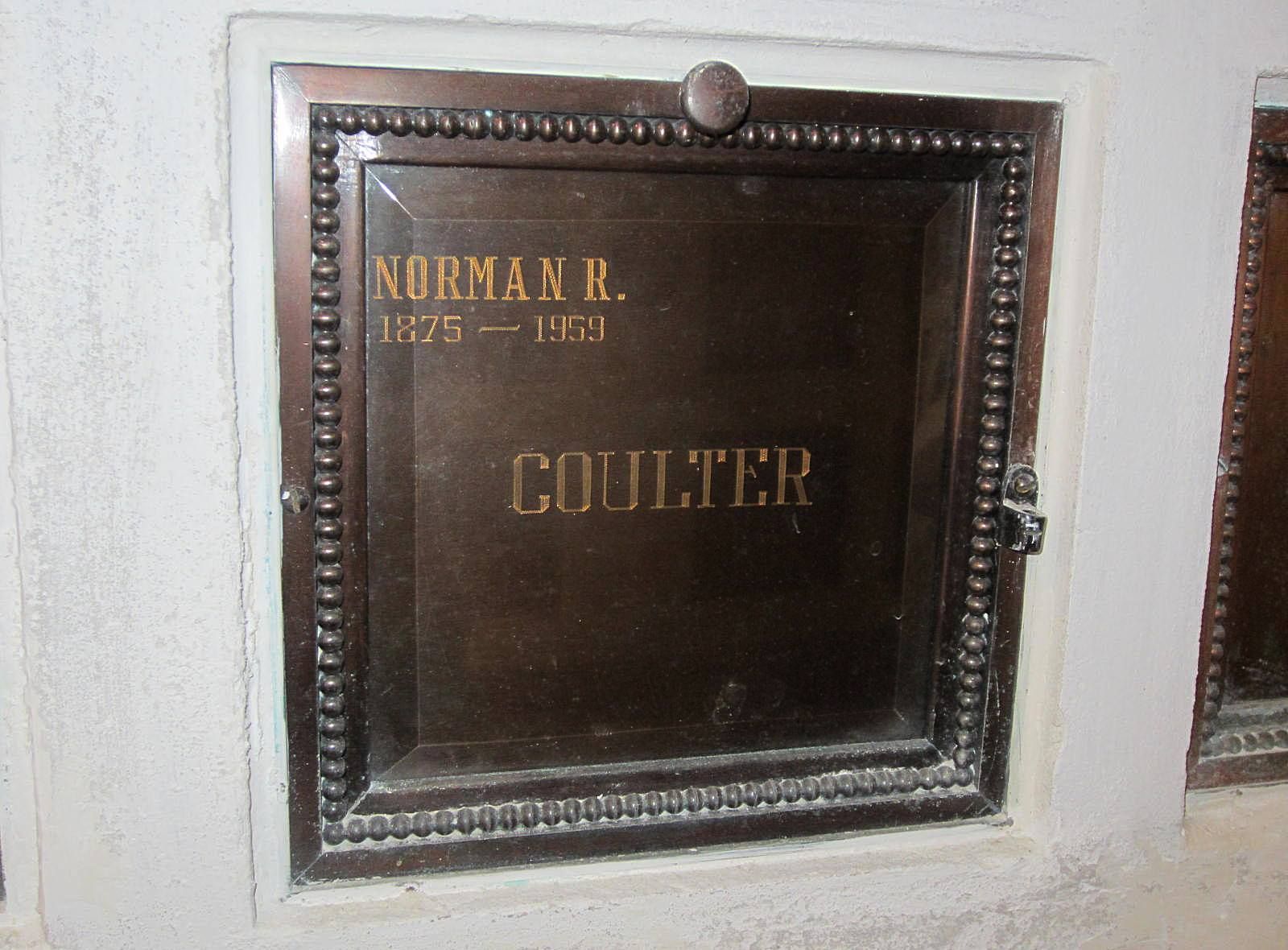

Norman Coulter's final years were tragic. He developed schizophrenia, and was confined to the California state mental hospital in Napa County, where he died at age 83 on 15 March 1959. He had outlived his only son and his five siblings and their families. His fourth wife Lillian survived him. Norman's ashes rest in a crypt on the top (4th) floor of the San Francisco Columbarium (now operated by the Neptune Society). Unlike swanky apartment buildings, where the penthouse commands a premium due to the better view, the top floor of the Columbarium contains the least-expensive niches. Lillian Coulter's ashes were added to the Coulter crypt after her death on 16 Jan 1987, age 84. Norman's only daughter, Therese Lockwood Coulter, died the same year, 11 June 1987, age 85, in Santa Clara County, California.

Norman's parents, Richard & Mary Jane (Stoughton) Coulter, and his sisters Eva Conlan and Inez Dowlin and their husbands are also inurned in San Francisco Columbarium. Also, Norman's brother-in-law, Ray R. Davison 1876-1922, "A Hero"---a veteran of the Spanish-American War.

The photo, above right, taken 1 February 1902, shows Norman and his second wife, Caroline Henrietta Pitkin (1870-1947), daughter of Charles Allen Pitkin & Henrietta C. Lockwood. Caroline married second on 1 January 1910 in San Jose, Santa Clara County, California, to Leonard Napoleon Brock (1872-1952). They had no children.

Norman R. Coulter lived through the great San Francisco earthquake and fire of April 18-19th, 1906. He wrote the following eyewitness account to his sister, Eva (Coulter) Conlan of Chicago.

San Jose, Cal. Apr 21, 1906

My Dear Sister:

I know you are anxious to hear all the news you can from California, so I will tell you a little of my experience. I had an awful time getting out of the city and narrowly escaped with my life in the great fire. The sights and sounds were something terrible and if I had not a strong constitution I never could have done the stunt I did. After the shake, which was awful, I started for the depot and ran right into the worst of the city, and before I knew it I was surrounded by blocks and blocks of fire. The streets were full of great cracks and holes and in one place for a whole block the ground was sucked down in the middle of the street, as wide as a street car and ten or fifteen feet deep, and water boiling up through holes in the earth. The roar of the flames was awful and the smoke was so thick I could scarely see and great chunks of burning pieces falling and dead people and wounded in the street--and half-naked, screaming, terrified wretches running aimlessly about. I thought to myself that I was caught like a rat in a trap. I could not go back the way I came; I could not go ahead for the bay was only a block or two away, and the only thing I could do was to run in front of the fire towards the hills. Just then I came in contact with a woman with two little boys, heading for the depot; I told her not to go there or she would be burned up, and there were no trains, as the shock had torn up the tracks. Somehow I was not quite coward enough to desert her, so I got the one boy, who was six years old, on my back and started to run, and she and the older boy followed as best they could. I stumbled along through the thick smoke and falling fire until I thought I could go no further. But the terrible roar behind me told me I must, so for a mile I packed the little fellow until we reached the foot of the great hills, then I let him down and led him by the hand, and helped the woman and other lad. On all sides were people streaming for the hills, and when I looked back over the city, from the hilltop, there were blocks and blocks of flames; such a sight I hope never to see again. Near the cemeteries the road was flooded with water pouring up out of the earth and I waded and carried the boy through water and mud. I must have carried him nearly four miles. Finally I left them at San Mateo. I walked forty miles that day with only a bite or two of bread to eat and all along the way were scenes of horror and desolation. I struggled on to Palo Alto which is fifteen miles from San Jose, where I got a train and when I got to San Jose I found it badly torn up, but kept on going until I reached home and found my family safe. I did not stop for they had not heard from Father and I was afraid he would be dead so I started for there, but when I came in sight of the house, my brother said I was staggering like a drunken man, and he got hold of me and got me to the lounge or I don't know what would have happened. I did not know I was so utterly exhausted. However, the next day I stood guard all day at the First National Bank with my rifle loaded. The shake did not injure Father in the least, and he was so sick, in fact he was less disturbed and took it more calmly then those who were well. I don't think there is any danger of more shakes, at least severe ones. I am not worried much about sister (Inez) and her husband, as their house being frame would not likely be shaken down and there is plenty of vacant space out towards the Presidio for them to escape the fire, so I think they are all right.

Kindest regards to all,

Norman R. Coulter

At age 21, Norman married on 4 March 1896 to Lulu Pearl Miles (1876-1898); but she died on March 3rd, and was buried on March 4th, on what would have been their second wedding anniversary. Wishing to make a fresh start, Norman left Butler in 1898, and bicycled from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to St. Louis, Missouri. He worked there a short while to save money for a train ticket to San Francisco, where he obtained employment at a mill on the waterfront.

Later he went to work in the big mill at Santa Clara, and studied architecture at night by correspondence courses. He became a draftsman with Bliss & Faville, San Francisco architects, and soon was head of their drafting department. After the 1906 earthquake, he worked with them rebuilding the St. Francis Hotel, which had been gutted by the fire, and also the St. Francis hospital.

Norman took the California state exam and became a licensed architect. He specialized in designing large public schools in northern and central California. He also built hotels, theatres, jails, the John Deere building---a "first" in design, necessitating the city pass a new building ordinance; and the Colonel Andrews Jewelry store in San Francisco---then one of the most beautiful buildings in the world, with murals by E. Tojetti, a Vatican muralist. The Portuguese government commissioned Norman to set up their ornate building at the 1915 Pan-American International Exposition in San Francisco. When World War I started, Norman drew up the first complete set of plans for a United States Navy destroyer. When Norman registered for the military draft on 12 September 1918, he was six feet tall, blue eyes, black hair, age 43, occupation: ship draftsman for Bethlehem Ship Builders, 20th Illinois Street, San Francisco; residence: 146-21st Street, San Francisco; spouse: Winifred King Coulter (the war ended two months later on 11 November 1918).

On a trip to Los Angeles in the 1920s, Norman was almost waylaid by a group of highwaymen; but he became suspicious and managed to elude them. As soon as he reached the nearest town, he contacted the sheriff of Santa Barbara and helped capture the gang, which had been terrorizing travelers for some time. Sheriff Ross appointed Norman a deputy sheriff, as did the sheriffs of Del Norte County and San Francisco County.

In the 1930s, Norman owned Big Tree Park, a resort lodge surrounded by giant redwoods at Requa, California. Norman was an expert photographer, and developed his own pictures. He used his photos of his redwoods on personally-designed Christmas cards promoting his resort. But thanks to the Great Depression, Big Tree Park failed; and Norman lost everything.

His personal life also included disappointments. Norman had a fine singing voice; and he and his second wife Caroline performed in church recitals. They wed on 2 July 1901, but the marriage ended in divorce; and Caroline took their two children: Therese and Richard with her to her father's home in San Jose, California. Young Richard---named after his grandfather---died at age 38 in 1943. Richard was childless; so the Coulter name is extinct on this branch of our family tree. (Norman's older brother James was also childless.)

Norman had no children by his third marriage, on 17 Aug 1916, to Winifred Cliff King (1880-1930), or his fourth, to Lillian Martha Arland (1902-1987), a native of Canada, who was the same age as Norman's only daughter, Therese. Lillian was Norman's photography assistant, both before and after their marriage. (Being an astute Coulter, Norman probably realized he would no longer have to pay Lillian an employee's salary after they married!)

Norman Coulter's final years were tragic. He developed schizophrenia, and was confined to the California state mental hospital in Napa County, where he died at age 83 on 15 March 1959. He had outlived his only son and his five siblings and their families. His fourth wife Lillian survived him. Norman's ashes rest in a crypt on the top (4th) floor of the San Francisco Columbarium (now operated by the Neptune Society). Unlike swanky apartment buildings, where the penthouse commands a premium due to the better view, the top floor of the Columbarium contains the least-expensive niches. Lillian Coulter's ashes were added to the Coulter crypt after her death on 16 Jan 1987, age 84. Norman's only daughter, Therese Lockwood Coulter, died the same year, 11 June 1987, age 85, in Santa Clara County, California.

Norman's parents, Richard & Mary Jane (Stoughton) Coulter, and his sisters Eva Conlan and Inez Dowlin and their husbands are also inurned in San Francisco Columbarium. Also, Norman's brother-in-law, Ray R. Davison 1876-1922, "A Hero"---a veteran of the Spanish-American War.

The photo, above right, taken 1 February 1902, shows Norman and his second wife, Caroline Henrietta Pitkin (1870-1947), daughter of Charles Allen Pitkin & Henrietta C. Lockwood. Caroline married second on 1 January 1910 in San Jose, Santa Clara County, California, to Leonard Napoleon Brock (1872-1952). They had no children.

Norman R. Coulter lived through the great San Francisco earthquake and fire of April 18-19th, 1906. He wrote the following eyewitness account to his sister, Eva (Coulter) Conlan of Chicago.

San Jose, Cal. Apr 21, 1906

My Dear Sister:

I know you are anxious to hear all the news you can from California, so I will tell you a little of my experience. I had an awful time getting out of the city and narrowly escaped with my life in the great fire. The sights and sounds were something terrible and if I had not a strong constitution I never could have done the stunt I did. After the shake, which was awful, I started for the depot and ran right into the worst of the city, and before I knew it I was surrounded by blocks and blocks of fire. The streets were full of great cracks and holes and in one place for a whole block the ground was sucked down in the middle of the street, as wide as a street car and ten or fifteen feet deep, and water boiling up through holes in the earth. The roar of the flames was awful and the smoke was so thick I could scarely see and great chunks of burning pieces falling and dead people and wounded in the street--and half-naked, screaming, terrified wretches running aimlessly about. I thought to myself that I was caught like a rat in a trap. I could not go back the way I came; I could not go ahead for the bay was only a block or two away, and the only thing I could do was to run in front of the fire towards the hills. Just then I came in contact with a woman with two little boys, heading for the depot; I told her not to go there or she would be burned up, and there were no trains, as the shock had torn up the tracks. Somehow I was not quite coward enough to desert her, so I got the one boy, who was six years old, on my back and started to run, and she and the older boy followed as best they could. I stumbled along through the thick smoke and falling fire until I thought I could go no further. But the terrible roar behind me told me I must, so for a mile I packed the little fellow until we reached the foot of the great hills, then I let him down and led him by the hand, and helped the woman and other lad. On all sides were people streaming for the hills, and when I looked back over the city, from the hilltop, there were blocks and blocks of flames; such a sight I hope never to see again. Near the cemeteries the road was flooded with water pouring up out of the earth and I waded and carried the boy through water and mud. I must have carried him nearly four miles. Finally I left them at San Mateo. I walked forty miles that day with only a bite or two of bread to eat and all along the way were scenes of horror and desolation. I struggled on to Palo Alto which is fifteen miles from San Jose, where I got a train and when I got to San Jose I found it badly torn up, but kept on going until I reached home and found my family safe. I did not stop for they had not heard from Father and I was afraid he would be dead so I started for there, but when I came in sight of the house, my brother said I was staggering like a drunken man, and he got hold of me and got me to the lounge or I don't know what would have happened. I did not know I was so utterly exhausted. However, the next day I stood guard all day at the First National Bank with my rifle loaded. The shake did not injure Father in the least, and he was so sick, in fact he was less disturbed and took it more calmly then those who were well. I don't think there is any danger of more shakes, at least severe ones. I am not worried much about sister (Inez) and her husband, as their house being frame would not likely be shaken down and there is plenty of vacant space out towards the Presidio for them to escape the fire, so I think they are all right.

Kindest regards to all,

Norman R. Coulter

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement