Residence: Henderson, Nevada, 54 years.

Services: 3 p.m. Friday at Palm Mortuary, 7600 Eastern Ave.

Survivors: Wife of 54 years, Carolyn; son, Steven of Las Vegas; three daughters, Cheree of Reno and Seanna and Lisa, both of Henderson; and four grandchildren.

Donations: To the Arnold-Jones-Evans Scholarship Fund, 1701 Whitney Mesa Drive, Henderson , Nevada 89014.

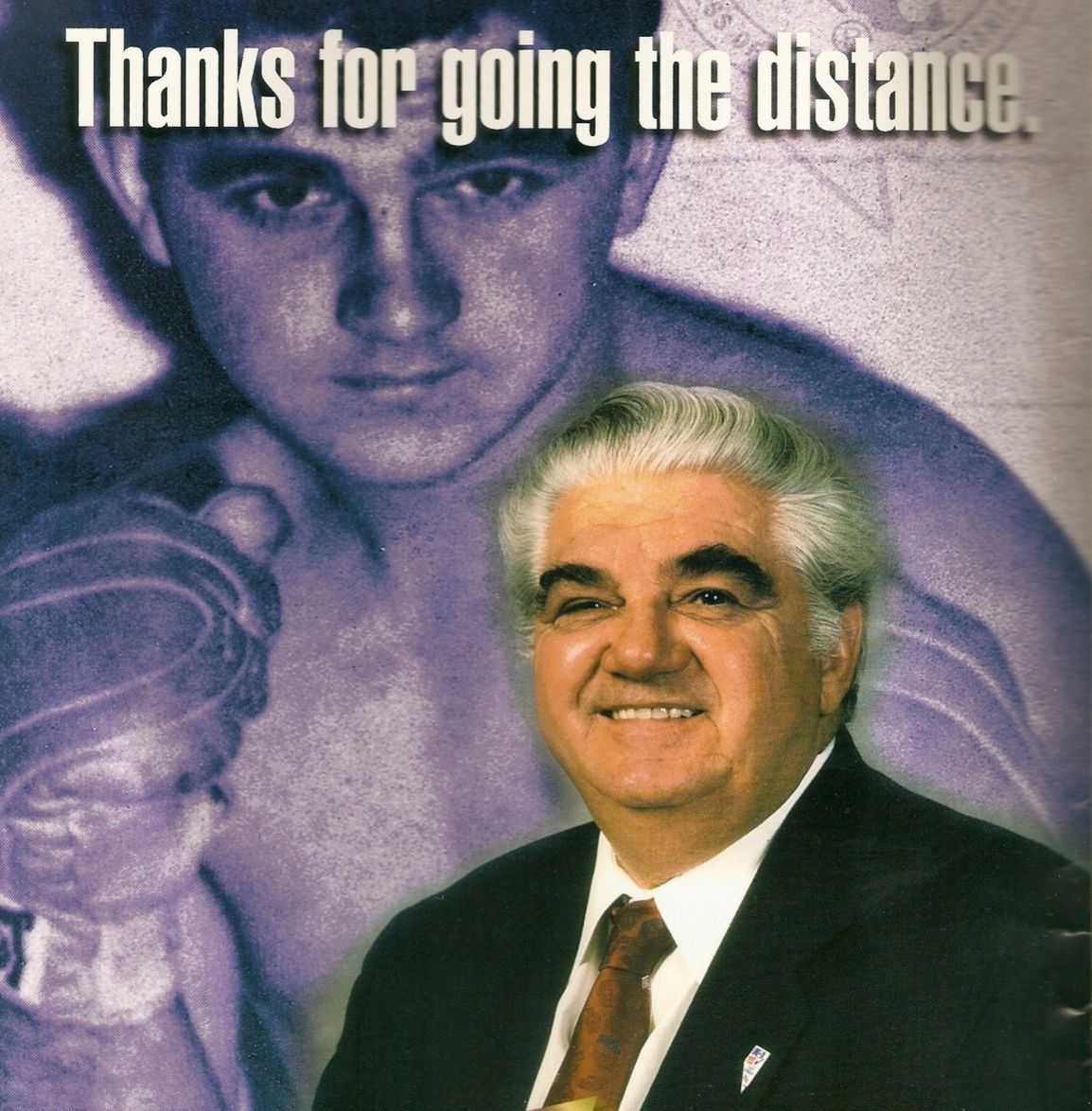

As the state's most powerful union leader in the 1980s and '90s, Claude "Blackie" Evans had great discipline organizing work forces by the thousands and haggling with management for the best deal for the working man.

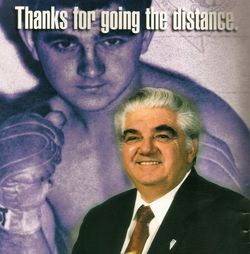

But for all of his strengths, the farm boy and Golden Gloves boxing champion from Missouri, who served seven terms as secretary-treasurer of the Nevada AFL-CIO, had one glaring weakness - a desire for heaping helpings of country cooking.

In the end, overindulgence brought on diabetes, shortened Evans' sterling career and contributed to his death Friday at his Henderson home. He was 71.

"It's ironic that my father used to say, 'More often than not, poor management in the workplace does its organizing for you,' " said Steven Evans, a state hearings officer.

"Although he tried to manage his diabetes a little better later in life, he could not shake eating habits he developed as a boy, when he consumed 15,000 calories then burned 15,000 calories working on the farm. The pork chops were still on his plate and he was always a beans and corn bread kind of guy."

Nevada Archivist, Guy Rocha, chuckled as he recalled that Evans' great appetite was as legendary as his hard work and unselfish dedication to union activities. "Evans was one of Nevada's three most significant post-World War II union leaders," Rocha said.

He likened Evans to venerable Laborers Union boss, James "Sailor" Ryan, now in his 90s and living in North Las Vegas, and former longtime Labor Commissioner, Stan Jones, in his 80s and residing in Reno.

"They are the triumvirate of Nevada labor," Rocha said.

"Blackie had the stereotypical look of a union leader - tough and gruff. He also had a certain pragmatism - a willingness to compromise when he needed to. He just wanted to get a bigger piece of pie for the workers , and in doing so he left his imprint on modern Nevada labor history."

Evans hitchhiked to Southern Nevada in 1953 with little or no intention of joining a union, much less becoming one of its most influential leaders. He wanted to get a job at the old Thunderbird Hotel-Casino, where his uncle worked. Instead, Evans, 17, lied about his age to get a job at Titanium Metals at the BMI plant, which had a minimum hiring age of 18.

Initially, Evans refused to pay the $3 monthly union dues, but reluctantly joined the union to help get a promotion.

"At first he didn't know what the union was because he was just a young cow-milker," said Jake Madill, a longtime friend and a steelworker at Titanium Metals for 36 years. "But things were happening on the job that Blackie didn't think were right, so he learned about the union and he learned real quick. He cared about people. He wanted to make things better."

Evans, who got his nickname from his dark complexion and wavy black hair, which later turned white, became a shop steward. Within months, he was elected vice-president of United Steelworkers of America Local 4856.

In 1961 he became president of that union and four years later settled a 62-day strike at Titanium Metals, securing a then unheard of cost-of-living salary increase, which laid the groundwork for the company paying what today is among the highest wages in the industry.

Evans called that negotiation his greatest labor victory.

Evans acknowledged that his overindulgence at the dining table and diabetes caused him to end his labor career early.

Evans spent his retirement in and out of hospitals, where, his son said, he was "the worst patient." But after giving his caregivers fits, Evans would apologize by giving them restaurant gift cards, Steven Evans said.

Days after being released from his most recent hospital stay in September, Evans got up during the night, fell and died from what his family learned was a massive heart attack.

Evans' regrets in life were few. Among them, he had not learned to speak Spanish, he had endorsed a few bad candidates and, at times, he had neglected his children because of his job. He made no apologies for his appetite, nor for enjoying a Bloody Mary each night before bedtime.

"It has been a hell of a ride and I have no regrets about the things I did to help the workers, who were always my first concern," Evans told the Sun for a 1999 story. "I never hesitated to open my mouth and be blunt. I was too darn dumb to lie and I was clean as a hound's tooth."

*************************

LAS VEGAS REVIEW JOURNAL -

29 Sep 2007

EX-LABOR LEADER DIES

Claude "Blackie" Evans, a Golden Gloves boxing champion during his youth in the Midwest, took up the fight for workers' rights as a powerful union boss and political activist in Nevada.

The longtime secretary-treasurer of Nevada State AFL-CIO, died Friday at his Henderson, Nevada home from a heart attack. He was 71.

Evans, who moved to Henderson in 1953 from Joplin, Missouri, was elected to the executive position in 1978, leading a labor organization with 130,000 members. He retired in 1999.

"As one of those whom you define as a labor union boss, I'm very proud that the union members of Nevada have elected me to my current position and the other union offices I've held for the past 40 years," Evans said at the 1998 Nevada State AFL-CIO convention at the Tropicana.

Nicknamed for his dark complexion and wavy black hair, Evans was commended by the Legislature in 1999 for his public service to people in Nevada.

"He was very helpful in any sort of fight or struggle we had," Culinary Local 226 Secretary-Treasurer D. Taylor said. "He was also a human being that took a personal interest in people. He never forgot where he came from, out of the plants in Henderson, Nevada. He always knew how members and their families had to deal with issues."

He started as a steel lathe operator for Titanium Metals in Henderson and, at age 22, was the youngest president of Steelworkers Local 4856. His election in 1978 prompted the withdrawal of the 26,000-member Culinary union, which was then the largest local in the state. The Culinary rejoined the AFL-CIO in 1981 after the organization elected a new secretary-treasurer.

Evans was preceded in death by his brother, Dan, former administrator of the Nevada Occupational Safety and Health Administration, who died of bone cancer in 2000 at age 50.

Former Governor, Bob Miller, remembered Blackie Evans as a hard-working and strong leader when he dealt with him as district attorney in the 1970s and '80s.

"He brought people together and, when he spoke, he had the force and respect of his membership behind him. There was no question he was the leader," Miller said. "We went through some significant labor-management issues during his years. He was a tireless advocate for working men and women, but he exerted his knowledge without intimidation. He got a lot accomplished because of his personality."

Former Nevada Governor and U.S. Senator, Richard Bryan, said Evans was the "quintessential" blue-collar worker from Henderson and one of his favorite labor leaders.

"I liked his personality and I liked the fact you always knew where you stood with Blackie. He was a pragmatist, very reasonable. You're always able to work out issues with him," Bryan said from Chicago.

In a statement, Sen. Harry Reid, D-Nev., said he is "deeply saddened" by Evans' passing.

"Throughout his life, he worked tirelessly for the hard-working men and women of Nevada and the nation," Reid said. "His efforts helped ensure working families a better standard of living. My thoughts are with his family during this time of sadness."

Evans liked to quote President Truman, who once said: "Those who say they love workers but hate unions are damn liars."

When he passed his duties to Danny Thompson in 1999, Evans said "it's a little strange" leaving the post after 46 years as a union man, starting as a steelworker in Henderson in 1953. He served eight years as head of the Nevada Industrial Commission under Gov. Mike O'Callaghan.

"It's been fun, it's been enjoyable," Evans told the Review-Journal at the time. "I've had the opportunity to meet some great people, some top labor officials. It was time. I had a couple of medical problems, which I got over."

In regard to the so-called "paycheck protection" initiative to block union dues from being used to support political candidates, Evans said, "We will not attack anyone simply because of their party affiliation, but based on their records and their positions on issues important to the working men and women of our state and nation."

Unions have historically contributed more to Democratic candidates than Republicans, but Evans noted that Nevada AFL-CIO membership included 25,000 registered Republicans.

Evans was born Nov. 26, 1935, in Duenweg, Mo. He is survived by his wife, Carolyn, of 54 years; son, Steven, of Las Vegas; daughters, Sheree, of Reno; Seanna and Lisa, both of Henderson; and four grandchildren.

Services are scheduled for 3 p.m. next Friday at Palm Mortuary at 7600 S. Eastern Ave.

Residence: Henderson, Nevada, 54 years.

Services: 3 p.m. Friday at Palm Mortuary, 7600 Eastern Ave.

Survivors: Wife of 54 years, Carolyn; son, Steven of Las Vegas; three daughters, Cheree of Reno and Seanna and Lisa, both of Henderson; and four grandchildren.

Donations: To the Arnold-Jones-Evans Scholarship Fund, 1701 Whitney Mesa Drive, Henderson , Nevada 89014.

As the state's most powerful union leader in the 1980s and '90s, Claude "Blackie" Evans had great discipline organizing work forces by the thousands and haggling with management for the best deal for the working man.

But for all of his strengths, the farm boy and Golden Gloves boxing champion from Missouri, who served seven terms as secretary-treasurer of the Nevada AFL-CIO, had one glaring weakness - a desire for heaping helpings of country cooking.

In the end, overindulgence brought on diabetes, shortened Evans' sterling career and contributed to his death Friday at his Henderson home. He was 71.

"It's ironic that my father used to say, 'More often than not, poor management in the workplace does its organizing for you,' " said Steven Evans, a state hearings officer.

"Although he tried to manage his diabetes a little better later in life, he could not shake eating habits he developed as a boy, when he consumed 15,000 calories then burned 15,000 calories working on the farm. The pork chops were still on his plate and he was always a beans and corn bread kind of guy."

Nevada Archivist, Guy Rocha, chuckled as he recalled that Evans' great appetite was as legendary as his hard work and unselfish dedication to union activities. "Evans was one of Nevada's three most significant post-World War II union leaders," Rocha said.

He likened Evans to venerable Laborers Union boss, James "Sailor" Ryan, now in his 90s and living in North Las Vegas, and former longtime Labor Commissioner, Stan Jones, in his 80s and residing in Reno.

"They are the triumvirate of Nevada labor," Rocha said.

"Blackie had the stereotypical look of a union leader - tough and gruff. He also had a certain pragmatism - a willingness to compromise when he needed to. He just wanted to get a bigger piece of pie for the workers , and in doing so he left his imprint on modern Nevada labor history."

Evans hitchhiked to Southern Nevada in 1953 with little or no intention of joining a union, much less becoming one of its most influential leaders. He wanted to get a job at the old Thunderbird Hotel-Casino, where his uncle worked. Instead, Evans, 17, lied about his age to get a job at Titanium Metals at the BMI plant, which had a minimum hiring age of 18.

Initially, Evans refused to pay the $3 monthly union dues, but reluctantly joined the union to help get a promotion.

"At first he didn't know what the union was because he was just a young cow-milker," said Jake Madill, a longtime friend and a steelworker at Titanium Metals for 36 years. "But things were happening on the job that Blackie didn't think were right, so he learned about the union and he learned real quick. He cared about people. He wanted to make things better."

Evans, who got his nickname from his dark complexion and wavy black hair, which later turned white, became a shop steward. Within months, he was elected vice-president of United Steelworkers of America Local 4856.

In 1961 he became president of that union and four years later settled a 62-day strike at Titanium Metals, securing a then unheard of cost-of-living salary increase, which laid the groundwork for the company paying what today is among the highest wages in the industry.

Evans called that negotiation his greatest labor victory.

Evans acknowledged that his overindulgence at the dining table and diabetes caused him to end his labor career early.

Evans spent his retirement in and out of hospitals, where, his son said, he was "the worst patient." But after giving his caregivers fits, Evans would apologize by giving them restaurant gift cards, Steven Evans said.

Days after being released from his most recent hospital stay in September, Evans got up during the night, fell and died from what his family learned was a massive heart attack.

Evans' regrets in life were few. Among them, he had not learned to speak Spanish, he had endorsed a few bad candidates and, at times, he had neglected his children because of his job. He made no apologies for his appetite, nor for enjoying a Bloody Mary each night before bedtime.

"It has been a hell of a ride and I have no regrets about the things I did to help the workers, who were always my first concern," Evans told the Sun for a 1999 story. "I never hesitated to open my mouth and be blunt. I was too darn dumb to lie and I was clean as a hound's tooth."

*************************

LAS VEGAS REVIEW JOURNAL -

29 Sep 2007

EX-LABOR LEADER DIES

Claude "Blackie" Evans, a Golden Gloves boxing champion during his youth in the Midwest, took up the fight for workers' rights as a powerful union boss and political activist in Nevada.

The longtime secretary-treasurer of Nevada State AFL-CIO, died Friday at his Henderson, Nevada home from a heart attack. He was 71.

Evans, who moved to Henderson in 1953 from Joplin, Missouri, was elected to the executive position in 1978, leading a labor organization with 130,000 members. He retired in 1999.

"As one of those whom you define as a labor union boss, I'm very proud that the union members of Nevada have elected me to my current position and the other union offices I've held for the past 40 years," Evans said at the 1998 Nevada State AFL-CIO convention at the Tropicana.

Nicknamed for his dark complexion and wavy black hair, Evans was commended by the Legislature in 1999 for his public service to people in Nevada.

"He was very helpful in any sort of fight or struggle we had," Culinary Local 226 Secretary-Treasurer D. Taylor said. "He was also a human being that took a personal interest in people. He never forgot where he came from, out of the plants in Henderson, Nevada. He always knew how members and their families had to deal with issues."

He started as a steel lathe operator for Titanium Metals in Henderson and, at age 22, was the youngest president of Steelworkers Local 4856. His election in 1978 prompted the withdrawal of the 26,000-member Culinary union, which was then the largest local in the state. The Culinary rejoined the AFL-CIO in 1981 after the organization elected a new secretary-treasurer.

Evans was preceded in death by his brother, Dan, former administrator of the Nevada Occupational Safety and Health Administration, who died of bone cancer in 2000 at age 50.

Former Governor, Bob Miller, remembered Blackie Evans as a hard-working and strong leader when he dealt with him as district attorney in the 1970s and '80s.

"He brought people together and, when he spoke, he had the force and respect of his membership behind him. There was no question he was the leader," Miller said. "We went through some significant labor-management issues during his years. He was a tireless advocate for working men and women, but he exerted his knowledge without intimidation. He got a lot accomplished because of his personality."

Former Nevada Governor and U.S. Senator, Richard Bryan, said Evans was the "quintessential" blue-collar worker from Henderson and one of his favorite labor leaders.

"I liked his personality and I liked the fact you always knew where you stood with Blackie. He was a pragmatist, very reasonable. You're always able to work out issues with him," Bryan said from Chicago.

In a statement, Sen. Harry Reid, D-Nev., said he is "deeply saddened" by Evans' passing.

"Throughout his life, he worked tirelessly for the hard-working men and women of Nevada and the nation," Reid said. "His efforts helped ensure working families a better standard of living. My thoughts are with his family during this time of sadness."

Evans liked to quote President Truman, who once said: "Those who say they love workers but hate unions are damn liars."

When he passed his duties to Danny Thompson in 1999, Evans said "it's a little strange" leaving the post after 46 years as a union man, starting as a steelworker in Henderson in 1953. He served eight years as head of the Nevada Industrial Commission under Gov. Mike O'Callaghan.

"It's been fun, it's been enjoyable," Evans told the Review-Journal at the time. "I've had the opportunity to meet some great people, some top labor officials. It was time. I had a couple of medical problems, which I got over."

In regard to the so-called "paycheck protection" initiative to block union dues from being used to support political candidates, Evans said, "We will not attack anyone simply because of their party affiliation, but based on their records and their positions on issues important to the working men and women of our state and nation."

Unions have historically contributed more to Democratic candidates than Republicans, but Evans noted that Nevada AFL-CIO membership included 25,000 registered Republicans.

Evans was born Nov. 26, 1935, in Duenweg, Mo. He is survived by his wife, Carolyn, of 54 years; son, Steven, of Las Vegas; daughters, Sheree, of Reno; Seanna and Lisa, both of Henderson; and four grandchildren.

Services are scheduled for 3 p.m. next Friday at Palm Mortuary at 7600 S. Eastern Ave.

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement