Son of Anthony and Phebe (Reed) Stoddard of Woodbury, Connecticut

Grandson of Eliakim and Joanna (Curtiss) Stoddard of Woodbury, Connecticut

Great-grandson of Rev. Anthony and Prudence (Welles) Stoddard of Woodbury, Connecticut

Amos Stoddard was born in his grandfather's house in Woodbury, Connecticut. The house was originally built circa 1720 for his great-grandfather, Reverend Anthony Stoddard, and was located on his parsonage homelot not far from his original parsonage house built in 1701. The house and an acre of land were deeded to his eldest surviving son, Eliakim Stoddard, in 1736. This house is still standing today (2021) in Woodbury, Connecticut and is operated as an inn.

At the time of Amos Stoddard's birth, the house was owned by Amos' uncle, Israel Stoddard, his father's brother. Israel Stoddard was deeded the house and one acre of land on March 31, 1752 as his part of his share of the distribution of his father's estate. Anthony Stoddard, the brother of Israel (and the father of Amos), had been living in the house with Israel and his other brothers since the death of their father in October 1749. Their mother, Joanna (Curtiss) Stoddard, remarried to Samuel Waller in 1750, and had relocated to Kent, Connecticut. She took the girls and youngest sons with her to Kent. Their eldest brother, John Stoddard (from whom the author of this biography descends), married Mary Atwood in April 1751 and relocated to Harwinton (near Watertown), Connecticut. Their brother Abiram soon left the house and relocated to Albany, New York where he died at the age of 19 in 1755. By circa 1754, only Israel and Anthony remained living in the house. Israel pursued an education as a doctor. Anthony farmed the lands of their deceased father and their grandfather.

Israel Stoddard married Elizabeth Reed on July 4, 1759. Anthony Stoddard then married his brother's wife's sister, Phebe Reed, in 1760 or 1761. Amos Stoddard was then born in the house they shared in Woodbury, Connecticut on October 26, 1762.

Amos' father Anthony sold his inherited lands (lands received from his father's estate as well as lands he received from his grandfather's estate after the death of Reverend Anthony Stoddard in September 1760) and relocated the family to New Framingham (the town name later changed to Lanesborough) in Massachusetts in 1763. His father later purchased a 100-acre farm in Lenox, Massachusetts from Nathan Mead in February 1773. This is where Amos Stoddard came of age. The Anthony Stoddard family home in Lenox, the childhood home of Amos Stoddard, is still standing. It has been preserved by the late David Kanter and his widow, Rori Kanter.

At the age of 16, Amos Stoddard enlisted in the Massachusetts militia in the spring of 1779. He was assigned to the 12th Massachusetts Regiment of Infantry. After walking over 100 miles to the New York highlands, he mustered-in with Inspector General Baron de Steuben at what is known today as West Point, New York. In November 1779, he reenlisted for the duration of the war and was assigned to Capt. Henry Burbeck's Company in the 3rd Continental Regiment of Artillery.

In the fall of 1780, while stationed at Stony Point, New York, Amos Stoddard witnessed the escape of General Benedict Arnold by boat and his boarding a British vessel in Haverstraw Bay. His artillery company then marched 20 miles south to Tappen, New York where Amos witnessed the hanging of British co-conspirator and spy, Major John Andre, while standing next to the wagon from which he was hung. He writes his personal account of the historical event in his autobiography. During his trip to England in 1791, Amos was requested and was given the opportunity to share his account of the event with Major Andre's brother in London, which was very emotional yet greatly appreciated. Forty years later, Major Andre's body was disinterred and transported back to England in November 1821 and he was laid to rest at Westminster Abby.

During the Campaign of 1781, Amos Stoddard served in an artillery company under the command of Capt. Joseph Savage and assigned to an army under the overall command of General Marquis de Lafayette. It was during this campaign that he participated in the Battle of Green Springs and the Siege of Yorktown. He was witness to the surrender of the British Army at Yorktown. The day after the surrender ceremony, he was one of a dozen soldiers sent into Yorktown where he participated in striking the British flag and raising the Stars and Stripes. His personal, first-hand account of his experiences during these events is included in his autobiography.

When the army was disbanded in early 1783, Amos Stoddard, at the time stationed at present-day West Point, New York, returned to the family home in Lenox, Massachusetts. Amos taught school at Lenox for a little more than a year after the War. In the spring of 1784, he traveled to Boston to receive his pay due for his military service. Back in 1783, while on his way home from the army, Amos encountered two gentlemen from Boston who offered to help him get a civilian career started. They told him to contact them if he was ever in Boston. He did. This led to Amos getting an introduction to Charles Cushing, the clerk of the Supreme Judicial Court, during this trip to Boston in 1784. As a result, Amos then became an assistant "writer" and clerk to Charles Cushing while also residing in his home. With the exception of a year-long break in 1787, when Amos was appointed an ensign in the state militia to support the Massachusetts governor and to serve to suppress Shays' Rebellion, Amos' employment with Charles Cushing lasted until his decision to study the law with Seth Padleford, Esq. at Taunton, Massachusetts in 1790. The story of Amos Stoddard's role in the suppression and defeat of Shays' Rebellion is told in great detail and is a highlight of Amos Stoddard's autobiography. Amos wholeheartedly supported the government over the plight of the insurrectionists — many of whom were neighbors and fellow veterans of the Revolution. His life was threatened as a result of his military position and support to the authorities. It is one of the very few personal and first-hand accounts of that largely unknown event in American history.

In December 1790, Amos took a break from his law studies to take a trip to London, England in an unsuccessful attempt to secure a Stoddard family estate for his uncle, John Stoddard (from whom the author of this biography descends). This trip lasted until August 1791. During his time in London, Amos wrote and published a 120-page political essay titled, "The Political Crisis: or, a Dissertation on the Rights of Man." Amos describes his trip and the details of his efforts to secure the estate (as well as an explanation for writing his political essay) in his autobiography.

.........................................................

As noted above, and at the risk of slightly jumping ahead of th e order of this story, in December 1790 Amos Stoddard took a break from his work for Charles Cushing at the Supreme Judicial Court and traveled to London to secure a family estate for his uncle, John Stoddard, of Watertown, Connecticut. While in London, Amos wrote to William Hyslop on May 14-15, 1791 and apprised him of his legal efforts to secure the estate and solicited his advice. William Hyslop was related to Amos Stoddard through marriage. He was married to Mehetable Stoddard, the daughter of David Stoddard. David was the son of Simeon Stoddard, the brother of Rev. Solomon Stoddard, from whom Amos descended. In his letter, Amos also mentions "Mr. Sumner" and suggests William Hyslop discuss the legal situation with him. This was referring to Increase Sumner, the son-in-law of William Hyslop (father of Elizabeth Hyslop Sumner). William Hyslop died in 1796. His son-in-law, Increase Sumner, then became governor of Massachusetts in 1797. About this time, Amos Stoddard was admitted to the Bar of Massachusetts (1796) and removed himself to Hallowell, Massachusetts. In 1798, Amos Stoddard was commissioned a captain in the U.S. Regiment of Artillerists and Engineers. He was assigned command at Portland. In February 1799, he wrote to secretary of war James McHenry and proposed that the fort, which had been greatly improved, receive a name. On May 3rd, James McHenry wrote to Major General Alexander Hamilton, to whom Capt. Amos Stoddard was reporting to at the time, and authorized the fort to be named "Fort Sumner" after the governor of Massachusetts, Increase Sumner. Governor Sumner then died on June 7, 1799. Nonetheless, the name change went ahead as authorized. On July 4th, 1799, Capt. Amos Stoddard announced the name of the fort to a gathering of several hundred spectators, including members of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. He also provided an oration which was printed and sold by E.A. Jenks, titled, "An Oration, Delivered Before The Citizens of Portland, And The Supreme Judicial Court In The Commonwealth of Massachusetts, On the Fourth Day of July 1799; Being the Anniversary of American Independence." On July 9th, Amos Stoddard wrote to Major General Alexander Hamilton the following: "Agreeably to your orders of the 14th communicated to me by Major Jackson, the fort at this place, on the 4th Instant, received the name of Sumner. The ceremony was passed in the presence of several hundred spectators; and I flatter myself, that the tribute of respect, so deservedly due to the memory and virtue of our late Governor, was not omitted on the occasion."

.........................................................

Upon his return from England, Amos continued his law studies with Seth Padleford at Taunton. He was admitted an attorney of the Supreme Judicial Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts on February 16, 1796. At that time, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts included the district of Maine. Maine was not yet a separate state.

Amos Stoddard, Esq. relocated to Hallowell, Massachusetts (today, Maine) in early 1796 and began to practice law and to dabble in politics. He was twice elected to represent Hallowell, Lincoln County, in the Massachusetts House of Representatives. With Federal elections approaching on February 6, 1797, political passions ran hot. The previous month, on December 10, 1796, Federalist candidate John Adams was the winner the first contested election in the United States, defeating Democratic-Republican candidate Thomas Jefferson to replace George Washington. Jefferson, by the rules at that time, became Vice President. Amos Stoddard was very happy: He was a Federalist, and a strong supporter of Washington and Adams.

At some point around this time, Amos Stoddard became an officer in the Massachusetts Militia serving as Brigadier Major & Inspector in the 2nd Brigade, 8th Division. This is evidenced by an annoucement he published on the front page of the Toscin (Hallowell) newspaper on May 5, 1797 in which he published "the following extract of the militia law of this commonwealth" and gave notice to the townships in the division that he would "inspect their respective magazines sometime in the months of July or August next" as required by law. The 8th Division militia officer corp included Brigadier General Henry Dearborn. Amos probably served in the militia up until the time he was commissioned a captain in the U.S. Army Corps of Artillerists and Engineers in May 1798.

In the first two weeks of January, 1797, Amos Stoddard wrote a lengthy political diatribe that was published in two issues of the Kennebeck Intelligencer spanning a week apart. The article covered the entire front page of each issue and half of the second page in the first issue. His political views were expressed under a pseudonym, "An Old Soldier," in which Amos advocated for a Federalist candidate to replace the incumbent Democratic-Republican representative (member of the House of Representatives), Henry Dearborn. Dearborn was then defeated in his bid for reelection several weeks later.

In September 1797, Amos had the occasion to meet Henry Dearborn in person. Their conversation evolved into a discussion of the articles of "the Old Soldier." Amos Stoddard then bravely admitted to Dearborn that he was "the Old Soldier" and that he was the author of the article. Amos followed-up a few days later to this face-to-face encounter of September 7th with a letter to Henry Dearborn. While he apologized in the letter for any misinterpretation of his words by the public, and "ask your pardon for the injury they may have occasioned to your character and feelings," he did not apologize for the content of the article or for stating his personal political beliefs. An image of the front page of the Kennebeck Intelligencer of January 14th and an image of the letter Amos Stoddard wrote to Henry Dearborn on September 10, 1797, which provided the evidence that Amos Stoddard had indeed been the author of the article by "An Old Soldier," are uploaded to this memorial. This is the first time in over 220 years that the author of the article published in the Kennebeck Intelligencer (and undoubtedly, excerpts of which were published in many other newspapers throughout Massachusetts) has been publicly divulged.

Amos Stoddard's honest confession later had repercussions for him when Thomas Jefferson defeated John Adams (and then after 36 ballot votes, Congress broke a tie between Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr) and Jefferson became president in 1800. President Jefferson then selected Henry Dearborn as his Secretary of War. As a result, Henry Dearborn then became the civilian commander of Captain Amos Stoddard of the 1st Regiment of Artillerists and Engineers. However, credit should be given to Henry Dearborn for being manly over this episode. While the memory of it may have caused some discomfort to Capt. Amos Stoddard, and while Henry Dearborn may have shared knowledge of it with other members of the cabinet that did cause Capt. Stoddard some difficulties during this period of his military career, there is no evidence that has been found that Secretary Dearborn used the past incident to take his revenge and severely punish Capt. Stoddard as a result.

Amos Stoddard, by his own admission, had a "roving disposition." He was often restless. After spending only about a year working as lawyer at Hallowell, Amos apparently became bored with the mundane aspect of actually being a lawyer. He first sought out an opportunity to serve abroad in England as a foreign representative in the Adams Administration. That effort was unsuccessful, but on May 28, 1798 , Amos Stoddard's name was submitted by President John Adams to the U.S. Senate for confirmation as a captain in the U.S. Army Corps of Artillerists and Engineers. Thus began Amos Stoddard's post-Revolutionary War military career.

Amos Stoddard's honorable military career is far too extensive to be covered in this relatively short biography. However, it is covered in great detail in the introduction to his autobiography. Since Amos Stoddard was a prolific writer, and because many of his letters to men such as his mentor, Henry Brubeck, thankfully survived, we can determine where Amos Stoddard was located or assigned during various years, what his thoughts were during those times, and what type of man Amos Stoddard was through his own words. His autobiography is especially useful in this regard.

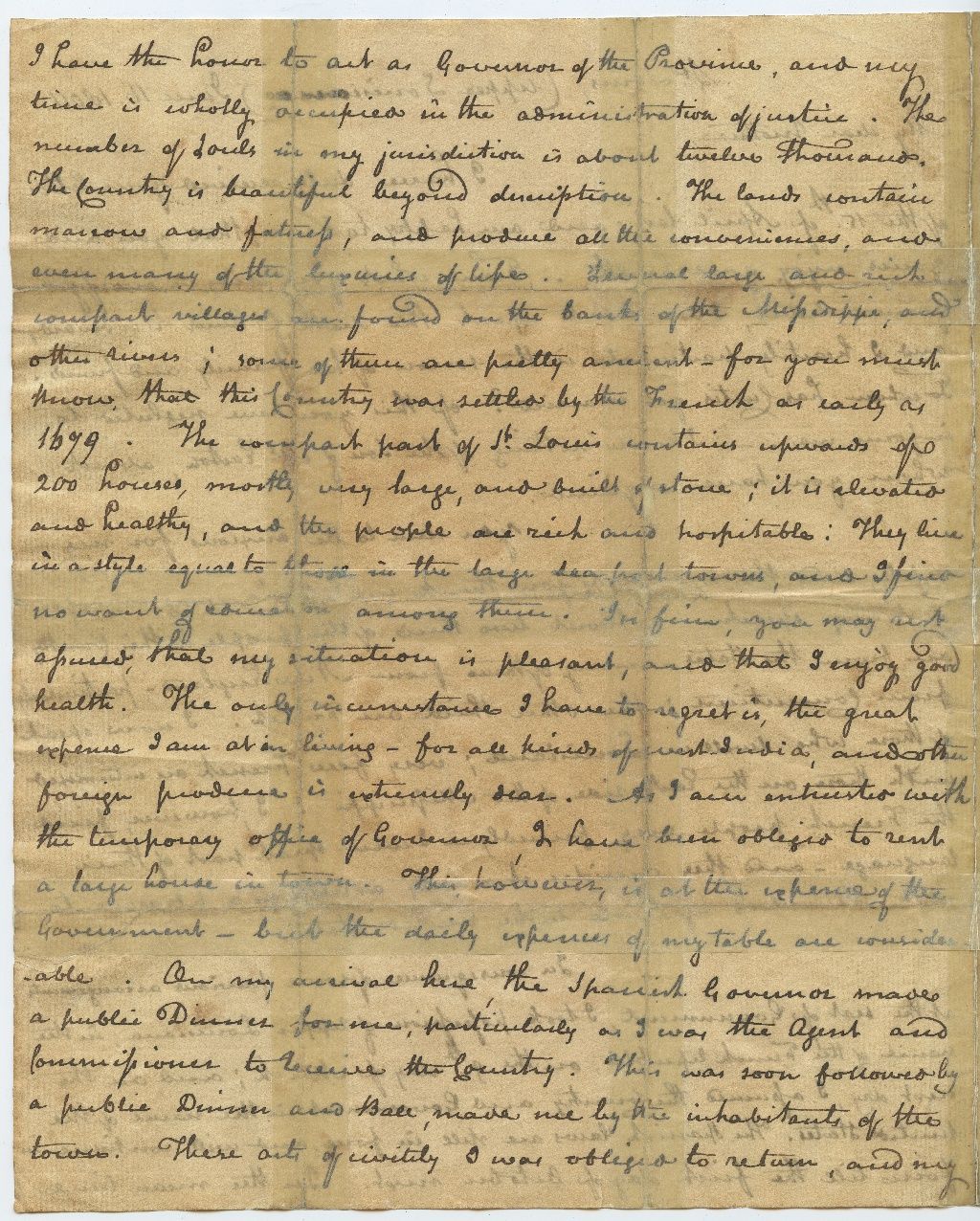

Amos Stoddard was a devoted member of the Masonic movement. He was a founding member of the Kennebeck Lodge at Hallowell in 1796 and he gave an oration to its members on St. John's Day (June 24th) in 1797. Amos loved to write, memorize and give orations on his political views and on Masonic virtue and history. He gave his orations from memory — not from written text. He gave a Masonic oration on St. John's Day (June 24th) and a celebratory oration on the Anniversary of American Independence at Portland, Massachusetts (today, Maine) in 1799 while commanding there at that time. At this same event on the 4th of July, he also announced the new name of the fort, Fort Sumner, after the late governor of Massachusetts, Gov. Increase Sumner. The site of this event and the fort is today Fort Sumner Park in Portland, Maine. He also gave a Masonic oration at Portsmouth, New Hampshire on St. John's Day (June 24th) in 1802 while commanding there. After his command at Portsmouth, in late 1802, Capt. Amos Stoddard, in command of an artillery company, was ordered westward on a secret mission. He ultimately ended-up at Kaskaskia on the east bank of the Mississippi River where he rendezvoused with the Lewis and Clark Expedition in the fall of 1803. He then took command at St. Louis in May 1804. Details of his significant role and largely unknown participation in this extraordinary period of American history can be found in the introduction to his autobiography.

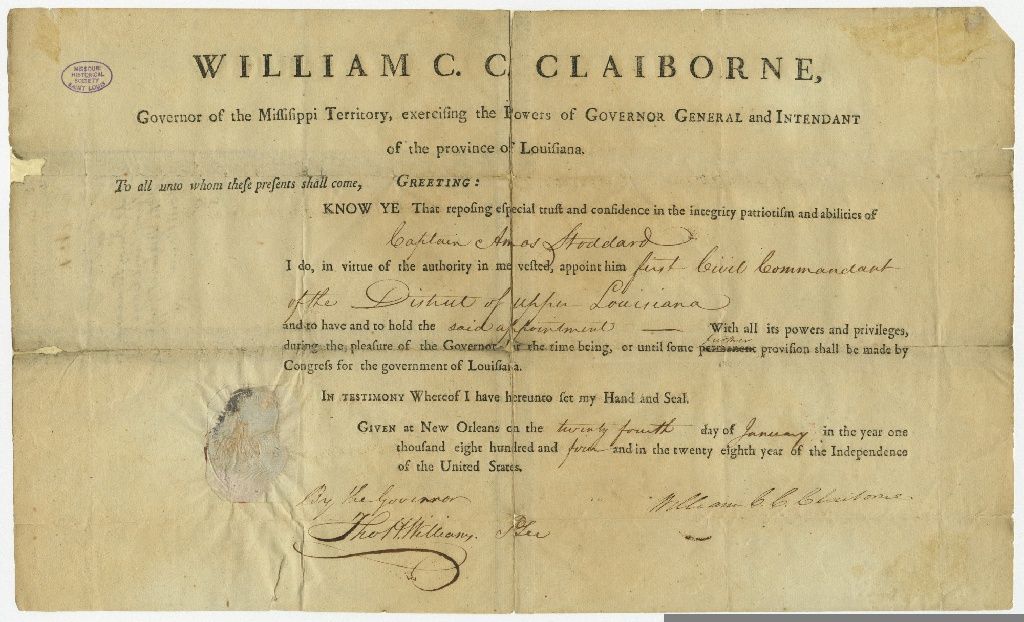

The high (and low) point of Amos Stoddard's life may well have been his commission as the first governor and civil commandment of Upper Louisiana and his role in the transfer of the Upper Louisiana to the United States on May 10, 1804. He represented both the Republic of France and the United States while transferring the territory from Spain to France on May 9th and from France to the United States on May 10th. This event is celebrated in St. Louis as "Three Flags Day." He also saw his friends, Capt. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, off on their expedition at St. Charles on May 21, 1804. Amos Stoddard was replaced as governor and first civil commandment by William Henry Harrison on October 1, 1804. In the fall of 1805, Capt. Amos Stoddard led a deputation of Indian chiefs to Washington and delivered them to President Jefferson at the Capital on January 6, 1806. Being ill at the time, Capt. Stoddard then took a leave of absence until the fall of 1806.

Capt. Amos Stoddard commanded at Fort Adams in the Mississippi Territory (and for a brief time, at Newport, Kentucky) between 1806 and 1808. He was promoted to major on June 30, 1807 after the resignation of his former nemesis, Major James Bruff. He also commanded for a short time in 1808 at Fort Dearborn (Chicago) before taking leave in the fall of 1808 until December 1809 to conduct an expedition of the Red River area of the Mississippi Territory and beyond for research in writing a book.

In December 1809, Major Amos Stoddard took command at Fort Columbus in New York harbor where he proceeded on writing his book. He became a member of the New York Historical Society at this time and likely used his membership and their library in New York in his publishing pursuit. His book, "Sketches, Historical and Descriptive, of Louisiana," was published in 1812 — just before the outbreak of hostilities with England. A copy of his book is included in the personal library of Thomas Jefferson at Monticello.

Prior to the outbreak of war in 1812, Amos Stoddard was involved in three significant events: One, he was a member of the first court martial trial for General James Wilkinson between September and Christmas 1811; Two, he published his opus, "Sketches, Historical and Descriptive, of Louisiana;" And three, he wrote and published, "Exercise for Garrison and Field Ordinance Together with Maneuvers" as a revision to General Tadeusz Kosciusko's "Manoeuvers," which became the first official manual of drill and tactics for the United States artillery and remained in use nearly until the Civil War.

After the court martial trail of General James Wilkinson ended on Christmas Day 1811 (Wilkinson was disappointingly acquitted), Major Amos Stoddard was assigned to the Department of War in Washington. After the Declaration of War was passed by Congress on June 18, 1812, Major Amos Stoddard began gathering intelligence and considering the best possible routes and methods for an attack of British forces in Canada. He then wrote, "Outlines of a Plan for an Attack on Canada." He submitted his strategic plan ("We ought to menace an attack at three places at once...") and tactics for an October attack of Canada to Secretary of War William Eustis on August 20, 1812. His plan was undoubtedly shared with President Madison. However, an alternative plan that was executed in December 1812 suffered from poor leadership and coordination and proved to be disastrously unsuccessful.

In September 1812 Major Amos Stoddard was ordered by Secretary of War Eustis to go to Pittsburg and command a forward supply base and to coordinate desperately needed supplies to the northwestern army commanded by William Henry Harrison. It proved to be an extremely difficult and thankless command. The northwestern army was an army comprised of untrained volunteer militia from various states led by inexperienced officers given their rank because of their local social status than their military leadership abilities. In mid-November, Major Amos Stoddard was then ordered by Secretary of War Eustis to join the northwestern army as the senior officer in charge of the artillery. He resisted this command...primarily because he didn't have the proper clothing with him to sustain him during a winter campaign in the field and because he mistrusted the militia army that had been assembled. He nonetheless followed his orders and rendezvoused with General Harrison at the Maumee River on or about February 1, 1813. The army immediately began constructing a defensive fort, at first named Camp Meigs and later named Fort Meigs.

In early March 1813, General Harrison departed Camp Meigs. Instead of placing his senior army officer, Major Amos Stoddard, in charge, he placed militia Brigadier General Joel Leftwich of Virginia, in charge. I can't help but think this had something to do with Harrison's past history with Major Stoddard back at St. Louis in 1804 and some jealousy he felt of Major Stoddard and his superior military knowledge and experience. He made the wrong decision. The choice of Leftwich was a complete disaster. Construction of the fort came to a complete stop. Torrential rains began. The militia men would not leave their tents to work. Some men even began disassembling the wooden fort walls they had built for firewood. Morale plummeted. To add insult to injury, General Leftwich and his Virginia militia, whose enlistment was ending, departed the camp on April 2nd (the Pennsylvania militia also departed on the 6th of April — although to their honor some men stayed until the 18th). As the senior officer, Major Amos Stoddard was placed in charge and took over command on April 2, 1813.

It was only after Major Stoddard took over command that efforts to complete the fort were restarted. He quickly issued organizational commands and priority directives while restoring discipline, confidence and morale. While he was only in command for 10 days, they were 10 days that ultimately saved many lives and provided the conditions for the army to survive the siege by the British and their Indian allies.

General Harrison returned to Fort Meigs on April 12th. Work on the Grand Traverse was already underway. By the time the British scouting elements arrived on the 26th everything was in order. The British were allowed to complete their encampment and position their artillery unmolested (yet another indication of the utter failure of leadership by Harrison) due to a shortage of artillery munitions. Harrison had apparently ordered munitions to be diverted to another location where he expected to face the enemy. This was yet another major error in Harrison's military understanding and leadership: Cannon are useless without shells. The British then commenced their assault of the fort in the early morning hours of May 1, 1813.

Major Amos Stoddard was on the field actively directing his artillery. His men were inexperienced militia volunteers who had limited training firing the guns. He was commanding at the Grand Battery when he was struck in the thigh by shrapnel from a British shell that exploded over the battery.

Major Stoddard was taken from the Grand Battery to an unknown location. As the senior officer he should have received immediate medical assistance and the best possible convalescent conditions. It is doubtful that he received and any such honor and respect. The "hospital department" of Harrison's army was totally deficient of medical supplies and was only staffed with young men with no medical knowledge, training or experience and not even worthy to be called "surgeons." There was no one capable to properly treat the wounded...and no medical supplies to ease their pain except for a gill of gin. Major Amos Stoddard may have spent the duration of the siege in no more than a tent with a dirt floor in the field. In any case, he contracted Tetanus.

Over the next ten days, Major Amos Stoddard's strength disintegrated from the symptoms of the bacterial infection known at that time as "lockjaw." It was a slow and painful death. His only satisfaction may have come when and if he understood that the fort and the men had withstood the assault and siege and that the British and their Indian allies had departed on May 9th.

Major Amos Stoddard then died at 11 o'clock on the night of May 11, 1813.

Major Stoddard was said to be buried in front of the Grand Battery — the place where he sustained his injury — on May 12, 1813 by the men of the 2nd Regiment of Artillery commanded by Capt. Daniel Cushing. In Capt. Daniel Cushing's diary, he states Major Stoddard was buried "in front of the Grand Battery." A granite monument honoring him is located inside the fort near the Grand Battery. However, it is not likely the actual site of burial. It is highly doubtful that Major Stoddard (or any other man, for that matter) was buried inside the fort walls. The military did not have a practice of burying human remains inside their fort walls. This was an active military installation housing hundreds and even thousands of men at the time — and it is unlikely they would bury their dead there. Perhaps they might have buried decaying corpses during the siege when they couldn't venture outside the fort walls...but Major Stoddard died after the British and Indians had departed the area and it was safe to leave the confines of the fort. It has been suggested by members of the Old Northwest Military History Association that Major Amos Stoddard may have been buried outside the picket "in front" of the Grand Battery. However, the area outside the fort wall "in front" of the battery facing the river is a steep hillside —so it is doubtful he was buried there either. In my opinion, it is most likely that his body was buried outside the fort yet near the Grand Battery. This possible burial location has been identified on a map reproduced by C.S. Van Tassel in 1935. From his map, the burial place of Major Amos Stoddard is identified as being between Blockhouse #1 and Blockhouse #7 near the Garrison Burial Ground. This makes perfect sense. The map has been uploaded to this memorial page. To download a copy, see: https://utdr.utoledo.edu/islandora/object/utoledo%3A2602

It should be noted that this 1935 map shows the second rendition of the layout of Fort Meigs. The Grand Battery is no longer present. The fort was reconfigured after the battles of 1813 to a smaller but more efficient fortress to accommodate a smaller number of men based there. The fort was ultimately abandoned and destroyed. The fort was reconstructed in 2001 as it was originally configured and this is the fort you can visit today at Perrysburg, Ohio.

The Ohio State Historic Preservation Office has jurisdiction over the Fort Meigs Historical Site. They have not approved a request to search for the burial site of Major Amos Stoddard. The following is part of their detailed response from Burt Logan to my request for a search and re-burial of the remains of Major Amos Stoddard:

"Representatives from the Ohio History Connection's historic sites, archaeology, and history sections met recently to review your request. Collectively they were knowledgeable of the site, the historic time period, and historic site operations throughout the Ohio History Connection. After careful consideration, I regret that we will not be able to allow the exhumation of Major Stoddard's remains, as explained below.

"Since 2002 the Ohio History Connection has maintained a moratorium on the excavation of human remains and their removal from the ground at any OHC sites. This stems from the discovery of pre-contact American Indian remains during the reconstruction of Fort Meigs in 2001-2002. Only in the most extreme circumstances of imminent danger to the preservation of human remains, such as their unexpected discovered during roadway construction or other related digging, can this moratorium be lifted."

————————————————————————————————————————————

The information contained in this biography is taken from the book, "The Autobiography Manuscript of Major Amos Stoddard, Edited and with an Introduction by Robert A. Stoddard," Deluxe Edition with Color Illustrations, from Robert Stoddard Publishing.

Reproduction prints of Amos Stoddard's "A Masonic Address...of the Kennebeck Lodge" delivered at Hallowell, Massachusetts in 1797, and his "An Oration...on the Fourth Day of July" delivered at Portland, Massachusetts in 1799, images of the original title pages which are found in the photo section, are available from Robert Stoddard Publishing through many online retailers.

————————————————————————————————————————————

Son of Anthony and Phebe (Reed) Stoddard of Woodbury, Connecticut

Grandson of Eliakim and Joanna (Curtiss) Stoddard of Woodbury, Connecticut

Great-grandson of Rev. Anthony and Prudence (Welles) Stoddard of Woodbury, Connecticut

Amos Stoddard was born in his grandfather's house in Woodbury, Connecticut. The house was originally built circa 1720 for his great-grandfather, Reverend Anthony Stoddard, and was located on his parsonage homelot not far from his original parsonage house built in 1701. The house and an acre of land were deeded to his eldest surviving son, Eliakim Stoddard, in 1736. This house is still standing today (2021) in Woodbury, Connecticut and is operated as an inn.

At the time of Amos Stoddard's birth, the house was owned by Amos' uncle, Israel Stoddard, his father's brother. Israel Stoddard was deeded the house and one acre of land on March 31, 1752 as his part of his share of the distribution of his father's estate. Anthony Stoddard, the brother of Israel (and the father of Amos), had been living in the house with Israel and his other brothers since the death of their father in October 1749. Their mother, Joanna (Curtiss) Stoddard, remarried to Samuel Waller in 1750, and had relocated to Kent, Connecticut. She took the girls and youngest sons with her to Kent. Their eldest brother, John Stoddard (from whom the author of this biography descends), married Mary Atwood in April 1751 and relocated to Harwinton (near Watertown), Connecticut. Their brother Abiram soon left the house and relocated to Albany, New York where he died at the age of 19 in 1755. By circa 1754, only Israel and Anthony remained living in the house. Israel pursued an education as a doctor. Anthony farmed the lands of their deceased father and their grandfather.

Israel Stoddard married Elizabeth Reed on July 4, 1759. Anthony Stoddard then married his brother's wife's sister, Phebe Reed, in 1760 or 1761. Amos Stoddard was then born in the house they shared in Woodbury, Connecticut on October 26, 1762.

Amos' father Anthony sold his inherited lands (lands received from his father's estate as well as lands he received from his grandfather's estate after the death of Reverend Anthony Stoddard in September 1760) and relocated the family to New Framingham (the town name later changed to Lanesborough) in Massachusetts in 1763. His father later purchased a 100-acre farm in Lenox, Massachusetts from Nathan Mead in February 1773. This is where Amos Stoddard came of age. The Anthony Stoddard family home in Lenox, the childhood home of Amos Stoddard, is still standing. It has been preserved by the late David Kanter and his widow, Rori Kanter.

At the age of 16, Amos Stoddard enlisted in the Massachusetts militia in the spring of 1779. He was assigned to the 12th Massachusetts Regiment of Infantry. After walking over 100 miles to the New York highlands, he mustered-in with Inspector General Baron de Steuben at what is known today as West Point, New York. In November 1779, he reenlisted for the duration of the war and was assigned to Capt. Henry Burbeck's Company in the 3rd Continental Regiment of Artillery.

In the fall of 1780, while stationed at Stony Point, New York, Amos Stoddard witnessed the escape of General Benedict Arnold by boat and his boarding a British vessel in Haverstraw Bay. His artillery company then marched 20 miles south to Tappen, New York where Amos witnessed the hanging of British co-conspirator and spy, Major John Andre, while standing next to the wagon from which he was hung. He writes his personal account of the historical event in his autobiography. During his trip to England in 1791, Amos was requested and was given the opportunity to share his account of the event with Major Andre's brother in London, which was very emotional yet greatly appreciated. Forty years later, Major Andre's body was disinterred and transported back to England in November 1821 and he was laid to rest at Westminster Abby.

During the Campaign of 1781, Amos Stoddard served in an artillery company under the command of Capt. Joseph Savage and assigned to an army under the overall command of General Marquis de Lafayette. It was during this campaign that he participated in the Battle of Green Springs and the Siege of Yorktown. He was witness to the surrender of the British Army at Yorktown. The day after the surrender ceremony, he was one of a dozen soldiers sent into Yorktown where he participated in striking the British flag and raising the Stars and Stripes. His personal, first-hand account of his experiences during these events is included in his autobiography.

When the army was disbanded in early 1783, Amos Stoddard, at the time stationed at present-day West Point, New York, returned to the family home in Lenox, Massachusetts. Amos taught school at Lenox for a little more than a year after the War. In the spring of 1784, he traveled to Boston to receive his pay due for his military service. Back in 1783, while on his way home from the army, Amos encountered two gentlemen from Boston who offered to help him get a civilian career started. They told him to contact them if he was ever in Boston. He did. This led to Amos getting an introduction to Charles Cushing, the clerk of the Supreme Judicial Court, during this trip to Boston in 1784. As a result, Amos then became an assistant "writer" and clerk to Charles Cushing while also residing in his home. With the exception of a year-long break in 1787, when Amos was appointed an ensign in the state militia to support the Massachusetts governor and to serve to suppress Shays' Rebellion, Amos' employment with Charles Cushing lasted until his decision to study the law with Seth Padleford, Esq. at Taunton, Massachusetts in 1790. The story of Amos Stoddard's role in the suppression and defeat of Shays' Rebellion is told in great detail and is a highlight of Amos Stoddard's autobiography. Amos wholeheartedly supported the government over the plight of the insurrectionists — many of whom were neighbors and fellow veterans of the Revolution. His life was threatened as a result of his military position and support to the authorities. It is one of the very few personal and first-hand accounts of that largely unknown event in American history.

In December 1790, Amos took a break from his law studies to take a trip to London, England in an unsuccessful attempt to secure a Stoddard family estate for his uncle, John Stoddard (from whom the author of this biography descends). This trip lasted until August 1791. During his time in London, Amos wrote and published a 120-page political essay titled, "The Political Crisis: or, a Dissertation on the Rights of Man." Amos describes his trip and the details of his efforts to secure the estate (as well as an explanation for writing his political essay) in his autobiography.

.........................................................

As noted above, and at the risk of slightly jumping ahead of th e order of this story, in December 1790 Amos Stoddard took a break from his work for Charles Cushing at the Supreme Judicial Court and traveled to London to secure a family estate for his uncle, John Stoddard, of Watertown, Connecticut. While in London, Amos wrote to William Hyslop on May 14-15, 1791 and apprised him of his legal efforts to secure the estate and solicited his advice. William Hyslop was related to Amos Stoddard through marriage. He was married to Mehetable Stoddard, the daughter of David Stoddard. David was the son of Simeon Stoddard, the brother of Rev. Solomon Stoddard, from whom Amos descended. In his letter, Amos also mentions "Mr. Sumner" and suggests William Hyslop discuss the legal situation with him. This was referring to Increase Sumner, the son-in-law of William Hyslop (father of Elizabeth Hyslop Sumner). William Hyslop died in 1796. His son-in-law, Increase Sumner, then became governor of Massachusetts in 1797. About this time, Amos Stoddard was admitted to the Bar of Massachusetts (1796) and removed himself to Hallowell, Massachusetts. In 1798, Amos Stoddard was commissioned a captain in the U.S. Regiment of Artillerists and Engineers. He was assigned command at Portland. In February 1799, he wrote to secretary of war James McHenry and proposed that the fort, which had been greatly improved, receive a name. On May 3rd, James McHenry wrote to Major General Alexander Hamilton, to whom Capt. Amos Stoddard was reporting to at the time, and authorized the fort to be named "Fort Sumner" after the governor of Massachusetts, Increase Sumner. Governor Sumner then died on June 7, 1799. Nonetheless, the name change went ahead as authorized. On July 4th, 1799, Capt. Amos Stoddard announced the name of the fort to a gathering of several hundred spectators, including members of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. He also provided an oration which was printed and sold by E.A. Jenks, titled, "An Oration, Delivered Before The Citizens of Portland, And The Supreme Judicial Court In The Commonwealth of Massachusetts, On the Fourth Day of July 1799; Being the Anniversary of American Independence." On July 9th, Amos Stoddard wrote to Major General Alexander Hamilton the following: "Agreeably to your orders of the 14th communicated to me by Major Jackson, the fort at this place, on the 4th Instant, received the name of Sumner. The ceremony was passed in the presence of several hundred spectators; and I flatter myself, that the tribute of respect, so deservedly due to the memory and virtue of our late Governor, was not omitted on the occasion."

.........................................................

Upon his return from England, Amos continued his law studies with Seth Padleford at Taunton. He was admitted an attorney of the Supreme Judicial Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts on February 16, 1796. At that time, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts included the district of Maine. Maine was not yet a separate state.

Amos Stoddard, Esq. relocated to Hallowell, Massachusetts (today, Maine) in early 1796 and began to practice law and to dabble in politics. He was twice elected to represent Hallowell, Lincoln County, in the Massachusetts House of Representatives. With Federal elections approaching on February 6, 1797, political passions ran hot. The previous month, on December 10, 1796, Federalist candidate John Adams was the winner the first contested election in the United States, defeating Democratic-Republican candidate Thomas Jefferson to replace George Washington. Jefferson, by the rules at that time, became Vice President. Amos Stoddard was very happy: He was a Federalist, and a strong supporter of Washington and Adams.

At some point around this time, Amos Stoddard became an officer in the Massachusetts Militia serving as Brigadier Major & Inspector in the 2nd Brigade, 8th Division. This is evidenced by an annoucement he published on the front page of the Toscin (Hallowell) newspaper on May 5, 1797 in which he published "the following extract of the militia law of this commonwealth" and gave notice to the townships in the division that he would "inspect their respective magazines sometime in the months of July or August next" as required by law. The 8th Division militia officer corp included Brigadier General Henry Dearborn. Amos probably served in the militia up until the time he was commissioned a captain in the U.S. Army Corps of Artillerists and Engineers in May 1798.

In the first two weeks of January, 1797, Amos Stoddard wrote a lengthy political diatribe that was published in two issues of the Kennebeck Intelligencer spanning a week apart. The article covered the entire front page of each issue and half of the second page in the first issue. His political views were expressed under a pseudonym, "An Old Soldier," in which Amos advocated for a Federalist candidate to replace the incumbent Democratic-Republican representative (member of the House of Representatives), Henry Dearborn. Dearborn was then defeated in his bid for reelection several weeks later.

In September 1797, Amos had the occasion to meet Henry Dearborn in person. Their conversation evolved into a discussion of the articles of "the Old Soldier." Amos Stoddard then bravely admitted to Dearborn that he was "the Old Soldier" and that he was the author of the article. Amos followed-up a few days later to this face-to-face encounter of September 7th with a letter to Henry Dearborn. While he apologized in the letter for any misinterpretation of his words by the public, and "ask your pardon for the injury they may have occasioned to your character and feelings," he did not apologize for the content of the article or for stating his personal political beliefs. An image of the front page of the Kennebeck Intelligencer of January 14th and an image of the letter Amos Stoddard wrote to Henry Dearborn on September 10, 1797, which provided the evidence that Amos Stoddard had indeed been the author of the article by "An Old Soldier," are uploaded to this memorial. This is the first time in over 220 years that the author of the article published in the Kennebeck Intelligencer (and undoubtedly, excerpts of which were published in many other newspapers throughout Massachusetts) has been publicly divulged.

Amos Stoddard's honest confession later had repercussions for him when Thomas Jefferson defeated John Adams (and then after 36 ballot votes, Congress broke a tie between Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr) and Jefferson became president in 1800. President Jefferson then selected Henry Dearborn as his Secretary of War. As a result, Henry Dearborn then became the civilian commander of Captain Amos Stoddard of the 1st Regiment of Artillerists and Engineers. However, credit should be given to Henry Dearborn for being manly over this episode. While the memory of it may have caused some discomfort to Capt. Amos Stoddard, and while Henry Dearborn may have shared knowledge of it with other members of the cabinet that did cause Capt. Stoddard some difficulties during this period of his military career, there is no evidence that has been found that Secretary Dearborn used the past incident to take his revenge and severely punish Capt. Stoddard as a result.

Amos Stoddard, by his own admission, had a "roving disposition." He was often restless. After spending only about a year working as lawyer at Hallowell, Amos apparently became bored with the mundane aspect of actually being a lawyer. He first sought out an opportunity to serve abroad in England as a foreign representative in the Adams Administration. That effort was unsuccessful, but on May 28, 1798 , Amos Stoddard's name was submitted by President John Adams to the U.S. Senate for confirmation as a captain in the U.S. Army Corps of Artillerists and Engineers. Thus began Amos Stoddard's post-Revolutionary War military career.

Amos Stoddard's honorable military career is far too extensive to be covered in this relatively short biography. However, it is covered in great detail in the introduction to his autobiography. Since Amos Stoddard was a prolific writer, and because many of his letters to men such as his mentor, Henry Brubeck, thankfully survived, we can determine where Amos Stoddard was located or assigned during various years, what his thoughts were during those times, and what type of man Amos Stoddard was through his own words. His autobiography is especially useful in this regard.

Amos Stoddard was a devoted member of the Masonic movement. He was a founding member of the Kennebeck Lodge at Hallowell in 1796 and he gave an oration to its members on St. John's Day (June 24th) in 1797. Amos loved to write, memorize and give orations on his political views and on Masonic virtue and history. He gave his orations from memory — not from written text. He gave a Masonic oration on St. John's Day (June 24th) and a celebratory oration on the Anniversary of American Independence at Portland, Massachusetts (today, Maine) in 1799 while commanding there at that time. At this same event on the 4th of July, he also announced the new name of the fort, Fort Sumner, after the late governor of Massachusetts, Gov. Increase Sumner. The site of this event and the fort is today Fort Sumner Park in Portland, Maine. He also gave a Masonic oration at Portsmouth, New Hampshire on St. John's Day (June 24th) in 1802 while commanding there. After his command at Portsmouth, in late 1802, Capt. Amos Stoddard, in command of an artillery company, was ordered westward on a secret mission. He ultimately ended-up at Kaskaskia on the east bank of the Mississippi River where he rendezvoused with the Lewis and Clark Expedition in the fall of 1803. He then took command at St. Louis in May 1804. Details of his significant role and largely unknown participation in this extraordinary period of American history can be found in the introduction to his autobiography.

The high (and low) point of Amos Stoddard's life may well have been his commission as the first governor and civil commandment of Upper Louisiana and his role in the transfer of the Upper Louisiana to the United States on May 10, 1804. He represented both the Republic of France and the United States while transferring the territory from Spain to France on May 9th and from France to the United States on May 10th. This event is celebrated in St. Louis as "Three Flags Day." He also saw his friends, Capt. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, off on their expedition at St. Charles on May 21, 1804. Amos Stoddard was replaced as governor and first civil commandment by William Henry Harrison on October 1, 1804. In the fall of 1805, Capt. Amos Stoddard led a deputation of Indian chiefs to Washington and delivered them to President Jefferson at the Capital on January 6, 1806. Being ill at the time, Capt. Stoddard then took a leave of absence until the fall of 1806.

Capt. Amos Stoddard commanded at Fort Adams in the Mississippi Territory (and for a brief time, at Newport, Kentucky) between 1806 and 1808. He was promoted to major on June 30, 1807 after the resignation of his former nemesis, Major James Bruff. He also commanded for a short time in 1808 at Fort Dearborn (Chicago) before taking leave in the fall of 1808 until December 1809 to conduct an expedition of the Red River area of the Mississippi Territory and beyond for research in writing a book.

In December 1809, Major Amos Stoddard took command at Fort Columbus in New York harbor where he proceeded on writing his book. He became a member of the New York Historical Society at this time and likely used his membership and their library in New York in his publishing pursuit. His book, "Sketches, Historical and Descriptive, of Louisiana," was published in 1812 — just before the outbreak of hostilities with England. A copy of his book is included in the personal library of Thomas Jefferson at Monticello.

Prior to the outbreak of war in 1812, Amos Stoddard was involved in three significant events: One, he was a member of the first court martial trial for General James Wilkinson between September and Christmas 1811; Two, he published his opus, "Sketches, Historical and Descriptive, of Louisiana;" And three, he wrote and published, "Exercise for Garrison and Field Ordinance Together with Maneuvers" as a revision to General Tadeusz Kosciusko's "Manoeuvers," which became the first official manual of drill and tactics for the United States artillery and remained in use nearly until the Civil War.

After the court martial trail of General James Wilkinson ended on Christmas Day 1811 (Wilkinson was disappointingly acquitted), Major Amos Stoddard was assigned to the Department of War in Washington. After the Declaration of War was passed by Congress on June 18, 1812, Major Amos Stoddard began gathering intelligence and considering the best possible routes and methods for an attack of British forces in Canada. He then wrote, "Outlines of a Plan for an Attack on Canada." He submitted his strategic plan ("We ought to menace an attack at three places at once...") and tactics for an October attack of Canada to Secretary of War William Eustis on August 20, 1812. His plan was undoubtedly shared with President Madison. However, an alternative plan that was executed in December 1812 suffered from poor leadership and coordination and proved to be disastrously unsuccessful.

In September 1812 Major Amos Stoddard was ordered by Secretary of War Eustis to go to Pittsburg and command a forward supply base and to coordinate desperately needed supplies to the northwestern army commanded by William Henry Harrison. It proved to be an extremely difficult and thankless command. The northwestern army was an army comprised of untrained volunteer militia from various states led by inexperienced officers given their rank because of their local social status than their military leadership abilities. In mid-November, Major Amos Stoddard was then ordered by Secretary of War Eustis to join the northwestern army as the senior officer in charge of the artillery. He resisted this command...primarily because he didn't have the proper clothing with him to sustain him during a winter campaign in the field and because he mistrusted the militia army that had been assembled. He nonetheless followed his orders and rendezvoused with General Harrison at the Maumee River on or about February 1, 1813. The army immediately began constructing a defensive fort, at first named Camp Meigs and later named Fort Meigs.

In early March 1813, General Harrison departed Camp Meigs. Instead of placing his senior army officer, Major Amos Stoddard, in charge, he placed militia Brigadier General Joel Leftwich of Virginia, in charge. I can't help but think this had something to do with Harrison's past history with Major Stoddard back at St. Louis in 1804 and some jealousy he felt of Major Stoddard and his superior military knowledge and experience. He made the wrong decision. The choice of Leftwich was a complete disaster. Construction of the fort came to a complete stop. Torrential rains began. The militia men would not leave their tents to work. Some men even began disassembling the wooden fort walls they had built for firewood. Morale plummeted. To add insult to injury, General Leftwich and his Virginia militia, whose enlistment was ending, departed the camp on April 2nd (the Pennsylvania militia also departed on the 6th of April — although to their honor some men stayed until the 18th). As the senior officer, Major Amos Stoddard was placed in charge and took over command on April 2, 1813.

It was only after Major Stoddard took over command that efforts to complete the fort were restarted. He quickly issued organizational commands and priority directives while restoring discipline, confidence and morale. While he was only in command for 10 days, they were 10 days that ultimately saved many lives and provided the conditions for the army to survive the siege by the British and their Indian allies.

General Harrison returned to Fort Meigs on April 12th. Work on the Grand Traverse was already underway. By the time the British scouting elements arrived on the 26th everything was in order. The British were allowed to complete their encampment and position their artillery unmolested (yet another indication of the utter failure of leadership by Harrison) due to a shortage of artillery munitions. Harrison had apparently ordered munitions to be diverted to another location where he expected to face the enemy. This was yet another major error in Harrison's military understanding and leadership: Cannon are useless without shells. The British then commenced their assault of the fort in the early morning hours of May 1, 1813.

Major Amos Stoddard was on the field actively directing his artillery. His men were inexperienced militia volunteers who had limited training firing the guns. He was commanding at the Grand Battery when he was struck in the thigh by shrapnel from a British shell that exploded over the battery.

Major Stoddard was taken from the Grand Battery to an unknown location. As the senior officer he should have received immediate medical assistance and the best possible convalescent conditions. It is doubtful that he received and any such honor and respect. The "hospital department" of Harrison's army was totally deficient of medical supplies and was only staffed with young men with no medical knowledge, training or experience and not even worthy to be called "surgeons." There was no one capable to properly treat the wounded...and no medical supplies to ease their pain except for a gill of gin. Major Amos Stoddard may have spent the duration of the siege in no more than a tent with a dirt floor in the field. In any case, he contracted Tetanus.

Over the next ten days, Major Amos Stoddard's strength disintegrated from the symptoms of the bacterial infection known at that time as "lockjaw." It was a slow and painful death. His only satisfaction may have come when and if he understood that the fort and the men had withstood the assault and siege and that the British and their Indian allies had departed on May 9th.

Major Amos Stoddard then died at 11 o'clock on the night of May 11, 1813.

Major Stoddard was said to be buried in front of the Grand Battery — the place where he sustained his injury — on May 12, 1813 by the men of the 2nd Regiment of Artillery commanded by Capt. Daniel Cushing. In Capt. Daniel Cushing's diary, he states Major Stoddard was buried "in front of the Grand Battery." A granite monument honoring him is located inside the fort near the Grand Battery. However, it is not likely the actual site of burial. It is highly doubtful that Major Stoddard (or any other man, for that matter) was buried inside the fort walls. The military did not have a practice of burying human remains inside their fort walls. This was an active military installation housing hundreds and even thousands of men at the time — and it is unlikely they would bury their dead there. Perhaps they might have buried decaying corpses during the siege when they couldn't venture outside the fort walls...but Major Stoddard died after the British and Indians had departed the area and it was safe to leave the confines of the fort. It has been suggested by members of the Old Northwest Military History Association that Major Amos Stoddard may have been buried outside the picket "in front" of the Grand Battery. However, the area outside the fort wall "in front" of the battery facing the river is a steep hillside —so it is doubtful he was buried there either. In my opinion, it is most likely that his body was buried outside the fort yet near the Grand Battery. This possible burial location has been identified on a map reproduced by C.S. Van Tassel in 1935. From his map, the burial place of Major Amos Stoddard is identified as being between Blockhouse #1 and Blockhouse #7 near the Garrison Burial Ground. This makes perfect sense. The map has been uploaded to this memorial page. To download a copy, see: https://utdr.utoledo.edu/islandora/object/utoledo%3A2602

It should be noted that this 1935 map shows the second rendition of the layout of Fort Meigs. The Grand Battery is no longer present. The fort was reconfigured after the battles of 1813 to a smaller but more efficient fortress to accommodate a smaller number of men based there. The fort was ultimately abandoned and destroyed. The fort was reconstructed in 2001 as it was originally configured and this is the fort you can visit today at Perrysburg, Ohio.

The Ohio State Historic Preservation Office has jurisdiction over the Fort Meigs Historical Site. They have not approved a request to search for the burial site of Major Amos Stoddard. The following is part of their detailed response from Burt Logan to my request for a search and re-burial of the remains of Major Amos Stoddard:

"Representatives from the Ohio History Connection's historic sites, archaeology, and history sections met recently to review your request. Collectively they were knowledgeable of the site, the historic time period, and historic site operations throughout the Ohio History Connection. After careful consideration, I regret that we will not be able to allow the exhumation of Major Stoddard's remains, as explained below.

"Since 2002 the Ohio History Connection has maintained a moratorium on the excavation of human remains and their removal from the ground at any OHC sites. This stems from the discovery of pre-contact American Indian remains during the reconstruction of Fort Meigs in 2001-2002. Only in the most extreme circumstances of imminent danger to the preservation of human remains, such as their unexpected discovered during roadway construction or other related digging, can this moratorium be lifted."

————————————————————————————————————————————

The information contained in this biography is taken from the book, "The Autobiography Manuscript of Major Amos Stoddard, Edited and with an Introduction by Robert A. Stoddard," Deluxe Edition with Color Illustrations, from Robert Stoddard Publishing.

Reproduction prints of Amos Stoddard's "A Masonic Address...of the Kennebeck Lodge" delivered at Hallowell, Massachusetts in 1797, and his "An Oration...on the Fourth Day of July" delivered at Portland, Massachusetts in 1799, images of the original title pages which are found in the photo section, are available from Robert Stoddard Publishing through many online retailers.

————————————————————————————————————————————