He evaded capture by Union forces just one day prior to Lee's surrender by ambushing and unhorsing (and not injuring) his pursuer. By this strategy and fortune, he was one of the few Confederate soldiers who did not have to walk home after the surrender!

1870 Mecklenburg, Va. census:

William O. 31 M W Farmer 300 100 Va

Mary L. 31 F W Keeps house

William E. 9 M W at home

Adelia M. 6 F W at home

Emma S. 3 F W

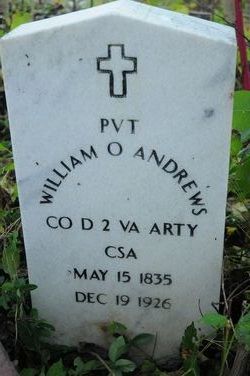

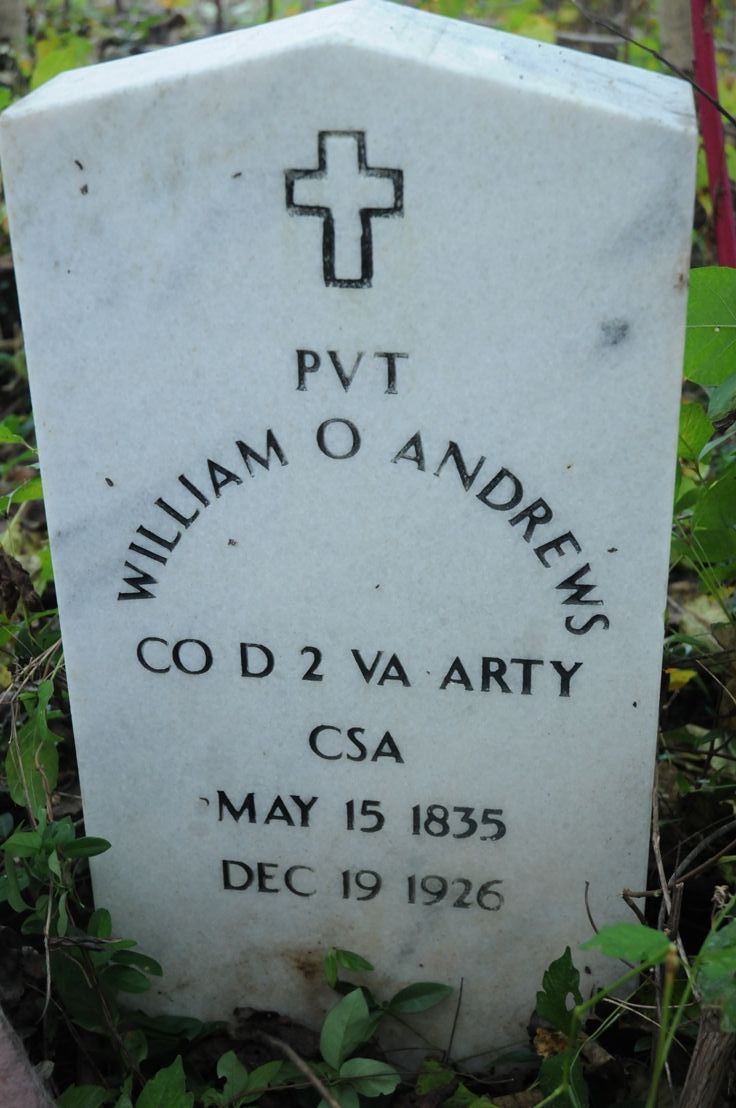

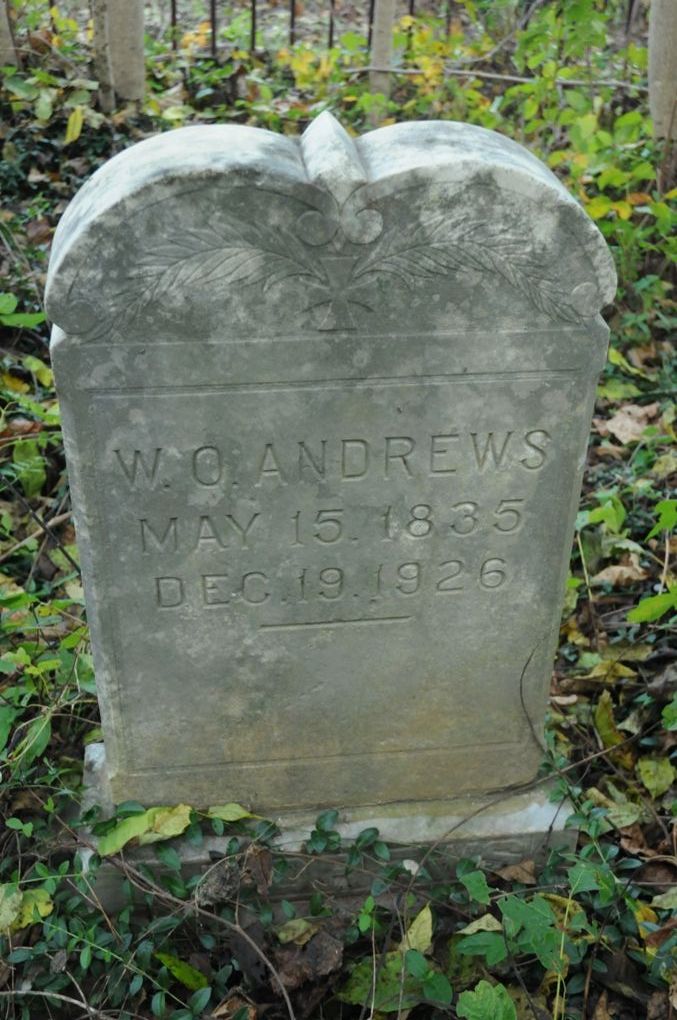

Caption for the accompany photograph:

Slaveholder The grave of a slaveholding rebel

William Oslin Andrews (BIRTH 15 MAY 1835 Mecklenburg, Virginia; DEATH 19 DEC 1926 Mecklenburg, Virginia. On December 14, 1859 he married Mary Lucas Binford (1837–1917) and they had the following children:

1. William Edward Andrews (BIRTH SEP 1860 Virginia; DEATH 22 APR 1924 Mecklenburg, Virginia). He married Susan G [Sisie] (1869–___) and they had the following children:

Roseland L Andrews (1890–____)

Ruth M Andrews (1893–____)

Claudia Andrews (1896-____)

2. Adelia M Andrews (1864–___)

3. Emma S Andrews (1868–____)

4. Martha Thweatt Andrews (1873–____)

5. Mary L Andrews (BIRTH 25 APR 1876 Mecklenburg, Virginia; DEATH 6 MAR 1961 Mecklenburg, Virginia)

6. Thomas L Andrews (BIRTH SEP 1880 Virginia; DEATH 18 AUG 1949 Mecklenburg, Virginia).

Causes of the Civil War – Part 3: Speaking to the Dead by William Xavier Andrews, Columbia, Tennessee, May 28, 2010:

Part 2 came out today and part 3 (below) will appear in the paper next Friday along with the picture of William Oslin Andrews' grave.

As a reenactor, I'm frequently asked to speak on the subject of the Civil War at historical associations, civic clubs and schools. I'm particularly fond of the schools because the invitations usually come from former students-turned-teachers and because my audience, whether fifth-graders or seniors, is always enthusiastic. Sometimes I bring my horse where, spurring the mount to a full gallop, I split watermelons with a saber. On one of these outings, the teacher, before turning the program over to me, announced "and, as we all know, slavery was not the cause of the Civil War." I was caught off guard because she had been one of my students and she never would have gotten the idea from me.

Interestingly, I recently came across a term paper written by my father when he was an undergraduate student at Vanderbilt in the mid 1930's. In it he made the same point. His paper agreed with many of the tenets of the Lost Cause, a literary and intellectual movement romanticizing the antebellum South and repudiating the slave-centered notion of the cause for secession. Dad was a product of his time and place, an impressionable youth expressing views that might earn him an A. Vanderbilt at the time was still basking in the brilliant glow of the Southern Agrarians or Fugitive writers whose views reflected Lost Cause sentiments.

I'm a direct descendant of Thomas Andrews who arrived in Virginia in 1685 and became a slaveholding planter. One of his descendants was Dr. Ephram Andrews who owned a hundred and nine slaves. Another, William O. Andrews, was a slave owner who fought for the Confederacy. The revisionist notion that slavery was an insignificant factor in secession would have come as a surprise to Ephram and William. They were willing to fight for their constitutional right to own other people.

In any case, if one wishes to refute the assertion that slavery was the fundamental cause of the Civil War, one should stick to secondary sources, particularly those written by early 20th century historians. The problem with original sources, particularly official documents, is that they punch gaping holes in the revisionist contention that slavery played merely an ancillary role in the secession crisis. Consulting original sources on this matter is like communicating with the dead. The authors of these documents speak to us from the most consequential time in our history. Their words carry weight because they were expressed by those who influenced the cause, course and outcome of the Civil War.

Between December 1860 and August of 1861, special conventions were called in the southern states to decide on the momentous question of secession. In these, the planter elites dominated the proceedings and drew up the secession documents – both the formal ordinances and the official explanations to justify separation. Protection of the institution of slavery was unambiguously a common thread in all.

South Carolina, referencing the non-slaveholding states in the North in its secession document, declared "They have encouraged and assisted thousands of our slaves to leave their homes … and have united in the election of a man to the high office of President of the United States whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery…"

In the attempt to bring additional states into the Confederacy, apologists for slavery in South Carolina declared that "there can be but one end by the submission by the South to the rule of a sectional anti-slavery government at Washington; and that end, directly or indirectly, must be the emancipation of the slaves of the South."

The Mississippi delegation wrote in its formal secession document "Our position is thoroughly indentified with the institution of slavery – the greatest material interest of the world… A blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization…There was no choice left us but submission to the mandates of abolition or a dissolution of the Union… We must either submit to degradation and to the loss of property worth four billions of money, or we must secede from the Union."

When Florida became the third state to secede, its preliminary resolution enumerated the reasons for its departure. Paramount was the election of Lincoln. The document reads: "All hope of preserving the Union on terms consistent with the safety and honor of the Slaveholding States has been finally dissipated by the recent indications of the strength of the anti-slavery sentiment in the Free States."

Georgia likewise justified its action on the Republican victory. "The prohibition of slavery in the territories, hostility to it everywhere, the equality of the black and white races, disregard of all constitutional guarantees in its favor, were boldly proclaimed by its leaders and applauded by its followers… Why was the Republican election victory cause for secession? Because the Republican Party had been formed in May of 1854 on the almost singular issue of opposition to slavery."

The above examples are typical of the secession documents of states leaving the Union in response to Lincoln's election Moreover, if one examines the Confederate Constitution itself, there can be no mistaking the central role that slavery played in its formulation. There is more than a little irony in that those revisionists who say that States' Rights was the central issue bringing on secession tend to overlook the fact that this new constitution denied its member states the right to secede or to end slavery within their borders.

I know that much of this flies in the face of what many of us have been told or taught by authority figures and I can appreciate how a coming to terms with it can be discomforting. I would suggest that you read the secession documents and the Confederate Constitution in their entirety for the purpose of contextual insight. It would also be of benefit to reflect on the eloquent words of the Great Emancipator in his Second Inaugural Address. Just weeks before the Lee's surrender and his own assassination, Lincoln laid the tragedy of civil war squarely at the feet of slavery.

"One eighth of the whole population were colored slaves… These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. And all knew that this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union even by war, while the Government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it…Yet, if God wills that [the war] continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as it was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said "the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether."

He evaded capture by Union forces just one day prior to Lee's surrender by ambushing and unhorsing (and not injuring) his pursuer. By this strategy and fortune, he was one of the few Confederate soldiers who did not have to walk home after the surrender!

1870 Mecklenburg, Va. census:

William O. 31 M W Farmer 300 100 Va

Mary L. 31 F W Keeps house

William E. 9 M W at home

Adelia M. 6 F W at home

Emma S. 3 F W

Caption for the accompany photograph:

Slaveholder The grave of a slaveholding rebel

William Oslin Andrews (BIRTH 15 MAY 1835 Mecklenburg, Virginia; DEATH 19 DEC 1926 Mecklenburg, Virginia. On December 14, 1859 he married Mary Lucas Binford (1837–1917) and they had the following children:

1. William Edward Andrews (BIRTH SEP 1860 Virginia; DEATH 22 APR 1924 Mecklenburg, Virginia). He married Susan G [Sisie] (1869–___) and they had the following children:

Roseland L Andrews (1890–____)

Ruth M Andrews (1893–____)

Claudia Andrews (1896-____)

2. Adelia M Andrews (1864–___)

3. Emma S Andrews (1868–____)

4. Martha Thweatt Andrews (1873–____)

5. Mary L Andrews (BIRTH 25 APR 1876 Mecklenburg, Virginia; DEATH 6 MAR 1961 Mecklenburg, Virginia)

6. Thomas L Andrews (BIRTH SEP 1880 Virginia; DEATH 18 AUG 1949 Mecklenburg, Virginia).

Causes of the Civil War – Part 3: Speaking to the Dead by William Xavier Andrews, Columbia, Tennessee, May 28, 2010:

Part 2 came out today and part 3 (below) will appear in the paper next Friday along with the picture of William Oslin Andrews' grave.

As a reenactor, I'm frequently asked to speak on the subject of the Civil War at historical associations, civic clubs and schools. I'm particularly fond of the schools because the invitations usually come from former students-turned-teachers and because my audience, whether fifth-graders or seniors, is always enthusiastic. Sometimes I bring my horse where, spurring the mount to a full gallop, I split watermelons with a saber. On one of these outings, the teacher, before turning the program over to me, announced "and, as we all know, slavery was not the cause of the Civil War." I was caught off guard because she had been one of my students and she never would have gotten the idea from me.

Interestingly, I recently came across a term paper written by my father when he was an undergraduate student at Vanderbilt in the mid 1930's. In it he made the same point. His paper agreed with many of the tenets of the Lost Cause, a literary and intellectual movement romanticizing the antebellum South and repudiating the slave-centered notion of the cause for secession. Dad was a product of his time and place, an impressionable youth expressing views that might earn him an A. Vanderbilt at the time was still basking in the brilliant glow of the Southern Agrarians or Fugitive writers whose views reflected Lost Cause sentiments.

I'm a direct descendant of Thomas Andrews who arrived in Virginia in 1685 and became a slaveholding planter. One of his descendants was Dr. Ephram Andrews who owned a hundred and nine slaves. Another, William O. Andrews, was a slave owner who fought for the Confederacy. The revisionist notion that slavery was an insignificant factor in secession would have come as a surprise to Ephram and William. They were willing to fight for their constitutional right to own other people.

In any case, if one wishes to refute the assertion that slavery was the fundamental cause of the Civil War, one should stick to secondary sources, particularly those written by early 20th century historians. The problem with original sources, particularly official documents, is that they punch gaping holes in the revisionist contention that slavery played merely an ancillary role in the secession crisis. Consulting original sources on this matter is like communicating with the dead. The authors of these documents speak to us from the most consequential time in our history. Their words carry weight because they were expressed by those who influenced the cause, course and outcome of the Civil War.

Between December 1860 and August of 1861, special conventions were called in the southern states to decide on the momentous question of secession. In these, the planter elites dominated the proceedings and drew up the secession documents – both the formal ordinances and the official explanations to justify separation. Protection of the institution of slavery was unambiguously a common thread in all.

South Carolina, referencing the non-slaveholding states in the North in its secession document, declared "They have encouraged and assisted thousands of our slaves to leave their homes … and have united in the election of a man to the high office of President of the United States whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery…"

In the attempt to bring additional states into the Confederacy, apologists for slavery in South Carolina declared that "there can be but one end by the submission by the South to the rule of a sectional anti-slavery government at Washington; and that end, directly or indirectly, must be the emancipation of the slaves of the South."

The Mississippi delegation wrote in its formal secession document "Our position is thoroughly indentified with the institution of slavery – the greatest material interest of the world… A blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization…There was no choice left us but submission to the mandates of abolition or a dissolution of the Union… We must either submit to degradation and to the loss of property worth four billions of money, or we must secede from the Union."

When Florida became the third state to secede, its preliminary resolution enumerated the reasons for its departure. Paramount was the election of Lincoln. The document reads: "All hope of preserving the Union on terms consistent with the safety and honor of the Slaveholding States has been finally dissipated by the recent indications of the strength of the anti-slavery sentiment in the Free States."

Georgia likewise justified its action on the Republican victory. "The prohibition of slavery in the territories, hostility to it everywhere, the equality of the black and white races, disregard of all constitutional guarantees in its favor, were boldly proclaimed by its leaders and applauded by its followers… Why was the Republican election victory cause for secession? Because the Republican Party had been formed in May of 1854 on the almost singular issue of opposition to slavery."

The above examples are typical of the secession documents of states leaving the Union in response to Lincoln's election Moreover, if one examines the Confederate Constitution itself, there can be no mistaking the central role that slavery played in its formulation. There is more than a little irony in that those revisionists who say that States' Rights was the central issue bringing on secession tend to overlook the fact that this new constitution denied its member states the right to secede or to end slavery within their borders.

I know that much of this flies in the face of what many of us have been told or taught by authority figures and I can appreciate how a coming to terms with it can be discomforting. I would suggest that you read the secession documents and the Confederate Constitution in their entirety for the purpose of contextual insight. It would also be of benefit to reflect on the eloquent words of the Great Emancipator in his Second Inaugural Address. Just weeks before the Lee's surrender and his own assassination, Lincoln laid the tragedy of civil war squarely at the feet of slavery.

"One eighth of the whole population were colored slaves… These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. And all knew that this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union even by war, while the Government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it…Yet, if God wills that [the war] continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as it was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said "the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether."

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

Advertisement