The Armijo family played a large role in the public life of Albuquerque. Manuel served as alcalde of Albuquerque in 1822 when he led an attack against the Apache Indians, and he served again as alcalde in1824-1825 and in 1830. His brother Francisco was alcalde in 1820, his brother Juan in 1823, brother Vicente in 1827, and Ambrosio in 1828, 1831, and 1834. In 1824 while serving as alcalde, Manuel Armijo was elected as alternate deputy to the congress in Chihuahua.

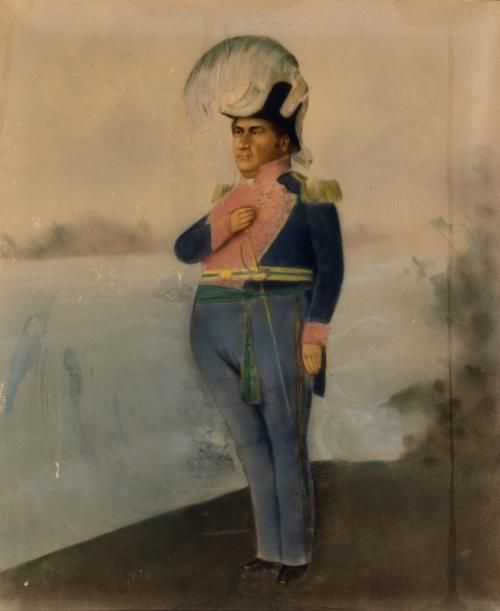

His first term as governor of New Mexico began in May 1827 and lasted until March 1829. As governor, Armijo was concerned with the poverty of many New Mexicans, caused in part by the concentration of arable lands in the hands of a few people and by drought conditions and poor crops. After his term as governor, Armijo served as alcalde of Albuquerque in 1830 and he became a successful entrepreneur, trading textiles and sheep in Mexico. For the next six years he lived in Albuquerque and was appointed to raise funds for New Mexico but the Rebellion of 1837 put Armijo back into the center of territorial politics. The appointed governor from central Mexico, Albino Perez, was murdered by the rebels in August 1837 and one of their leaders, José Gonzalez from Taos, was placed in power. Members of the merchant and landowning classes came together to oppose Gonzalez and the rebels with a troop of some 600 volunteers organized in Santa Fe under Captain José Caballero and another 400 men from the Rio Abajo. All of the volunteer troops were put under the leadership of Manuel Armijo. They received considerable material support from the American traders in Santa Fe and also from wealthy Hispanos.

In response to his victory over the rebels the central government of Mexico again appointed Armijo governor but failed to provide the necessary resources to fund his administration. In the early 1840s Armijo's major concern was not the Americans but the Texans. The expansionist policies of the Republic of Texas culminated in the ill-fated Texas-Santa Fe expedition in 1841, in which a group of over 300 Texans marched to New Mexico with the intention of wresting that territory from Mexican sovereignty. Governor Armijo was well aware of the expedition and its intentions, and he kept in close touch with authorities in Mexico who, still smarting from the loss of Texas, gave him material aid in order to resist the invasion. He had up-to-date news on the progress of the Texans, thanks to the arrival in Taos in early September 1841, of two guides who had deserted the expedition.

In March 1844 Armijo resigned as governor and returned to Albuquerque. Succeeding governors caused much discontent among both the Americans and Hispanos in New Mexico by raising tariffs on the goods of the traders and attempting to tax the populace. In July 1845 Armijo was re-appointed to his third and final term as governor. Armijo was welcomed back into office because his policies were more lenient and enlightened than those of his predecessors, and his relations with the Americans had become quite friendly. But, with the beginning of the Mexican-American War in May 1846, Armijo attempted to rally the populace to resist the coming American invasion. He also requested and was promised troops from Mexico though none arrived before the threatened invasion. Armijo's call to arms brought an enthusiastic but completely untrained crowd of New Mexicans to Santa Fe to volunteer for the defense of the territory.

Armijo was accused of cowardice and treason; American writers, in their negative depiction of Armijo, have suggested that he accepted a bribe from the Americans for not opposing Kearny, but there is no concrete evidence that he did. The most generous explanation of his actions is that he realized there was little chance of defeating the Americans who were better armed and better provisioned. His volunteers did not have adequate weapons or food supplies and lacked professional leaders or any military training, and he knew from experience that support from Mexico would be minimal if there was any at all. When met by English trader George Ruxton in Chihuahua shortly after his retreat, Armijo said to him: "I had but seventy-five men to fight three thousand. What could I do?" While this is somewhat of a self-justifying exaggeration, it does express Armijo's view that resistance against the superior forces of the United States was hopeless. Armijo went first to Chihuahua and then to Mexico City where he was tried on charges of treason. He returned to Chihuahua in October 1849 and was jailed by General Angel Trias, but the Mexican Supreme Court and the Congress found that there was not enough evidence to convict him, and he was released in January 1850. Armijo moved back to New Mexico and died at his home in Lemitar in January 1854.

by William H. Wroth - New Mexico State Historian

He was the son of Vicente Ferrer Duran de Armijo (1746-1806) and Maria Barbara Casilda Duran y Chaves (~1753-1798)

The Armijo family played a large role in the public life of Albuquerque. Manuel served as alcalde of Albuquerque in 1822 when he led an attack against the Apache Indians, and he served again as alcalde in1824-1825 and in 1830. His brother Francisco was alcalde in 1820, his brother Juan in 1823, brother Vicente in 1827, and Ambrosio in 1828, 1831, and 1834. In 1824 while serving as alcalde, Manuel Armijo was elected as alternate deputy to the congress in Chihuahua.

His first term as governor of New Mexico began in May 1827 and lasted until March 1829. As governor, Armijo was concerned with the poverty of many New Mexicans, caused in part by the concentration of arable lands in the hands of a few people and by drought conditions and poor crops. After his term as governor, Armijo served as alcalde of Albuquerque in 1830 and he became a successful entrepreneur, trading textiles and sheep in Mexico. For the next six years he lived in Albuquerque and was appointed to raise funds for New Mexico but the Rebellion of 1837 put Armijo back into the center of territorial politics. The appointed governor from central Mexico, Albino Perez, was murdered by the rebels in August 1837 and one of their leaders, José Gonzalez from Taos, was placed in power. Members of the merchant and landowning classes came together to oppose Gonzalez and the rebels with a troop of some 600 volunteers organized in Santa Fe under Captain José Caballero and another 400 men from the Rio Abajo. All of the volunteer troops were put under the leadership of Manuel Armijo. They received considerable material support from the American traders in Santa Fe and also from wealthy Hispanos.

In response to his victory over the rebels the central government of Mexico again appointed Armijo governor but failed to provide the necessary resources to fund his administration. In the early 1840s Armijo's major concern was not the Americans but the Texans. The expansionist policies of the Republic of Texas culminated in the ill-fated Texas-Santa Fe expedition in 1841, in which a group of over 300 Texans marched to New Mexico with the intention of wresting that territory from Mexican sovereignty. Governor Armijo was well aware of the expedition and its intentions, and he kept in close touch with authorities in Mexico who, still smarting from the loss of Texas, gave him material aid in order to resist the invasion. He had up-to-date news on the progress of the Texans, thanks to the arrival in Taos in early September 1841, of two guides who had deserted the expedition.

In March 1844 Armijo resigned as governor and returned to Albuquerque. Succeeding governors caused much discontent among both the Americans and Hispanos in New Mexico by raising tariffs on the goods of the traders and attempting to tax the populace. In July 1845 Armijo was re-appointed to his third and final term as governor. Armijo was welcomed back into office because his policies were more lenient and enlightened than those of his predecessors, and his relations with the Americans had become quite friendly. But, with the beginning of the Mexican-American War in May 1846, Armijo attempted to rally the populace to resist the coming American invasion. He also requested and was promised troops from Mexico though none arrived before the threatened invasion. Armijo's call to arms brought an enthusiastic but completely untrained crowd of New Mexicans to Santa Fe to volunteer for the defense of the territory.

Armijo was accused of cowardice and treason; American writers, in their negative depiction of Armijo, have suggested that he accepted a bribe from the Americans for not opposing Kearny, but there is no concrete evidence that he did. The most generous explanation of his actions is that he realized there was little chance of defeating the Americans who were better armed and better provisioned. His volunteers did not have adequate weapons or food supplies and lacked professional leaders or any military training, and he knew from experience that support from Mexico would be minimal if there was any at all. When met by English trader George Ruxton in Chihuahua shortly after his retreat, Armijo said to him: "I had but seventy-five men to fight three thousand. What could I do?" While this is somewhat of a self-justifying exaggeration, it does express Armijo's view that resistance against the superior forces of the United States was hopeless. Armijo went first to Chihuahua and then to Mexico City where he was tried on charges of treason. He returned to Chihuahua in October 1849 and was jailed by General Angel Trias, but the Mexican Supreme Court and the Congress found that there was not enough evidence to convict him, and he was released in January 1850. Armijo moved back to New Mexico and died at his home in Lemitar in January 1854.

by William H. Wroth - New Mexico State Historian

He was the son of Vicente Ferrer Duran de Armijo (1746-1806) and Maria Barbara Casilda Duran y Chaves (~1753-1798)

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement