He was an Artist and Teacher, and is survived by two daughters, Flora Stone and her husband, Jerome and Cecilia Carter; two grandchildren, Kayla & Natalie Stone; sister and brother-in-law, Shirley & Levon Chestnut; brother and sister-in-law, Alford & Alice Carter; two aunts, Luvenia Taylor & Louise Johnson; his former wife, Mae Carter, and other relatives.

Interment followed funeral services conducted at the Antioch Church of Christ, Alexandria, VA, Saturday, December 27, 2008.

********************************************

Whatever Happened To ... artist Big Al Carter?

By Kris Coronado

Sunday, January 31, 2010

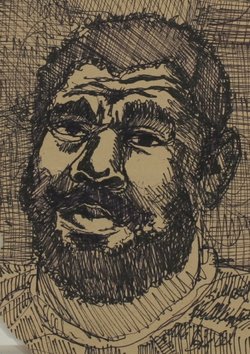

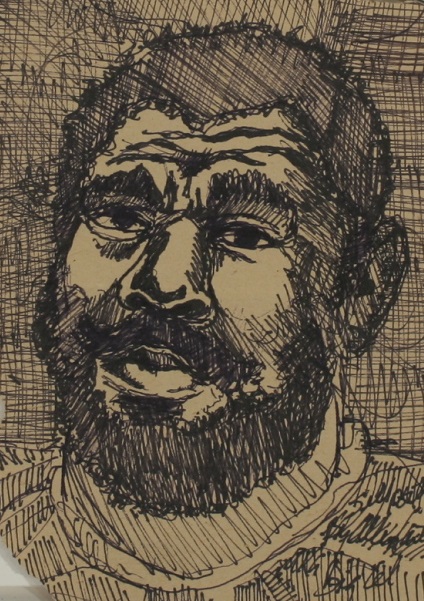

Allen "Big Al" Carter painted by the numbers -- big numbers. Three floors of the artist's Alexandria home were crammed floor to ceiling with his life's work. When profiled by The Washington Post Magazine in May 2006, Carter estimated he had 20,000 pieces -- from intricate etchings to enormous day-glo paintings -- in the 900-square-foot space. "His creative impulse was everywhere," says longtime friend Steven Tepper, 42.

Carter, 61, died of complications from diabetes on Dec. 18, 2008, leaving his daughters, Flora Stone, 35, and Cecilia Carter, 29, facing a challenge: what to do with all that art.

Despite the extent of his talent, Carter had shied away from the wheeling and dealing of the art scene. While he'd sometimes lend pieces for temporary gallery installations, he didn't avidly pursue the limelight and was reluctant to sell his compositions.

Art speculators contacted Carter's daughters as early as the weekend of his death. "I was, like, 'Uh, no,' " Stone says. "We weren't interested in selling his work. We were looking toward promoting him, as if he's still here."

Easy enough: All she and her sister had to do was sift through an avalanche of art in their free time (Stone works at Hampton University, and Carter is an undergrad at Thomas Nelson Community College). The sisters turned to Tepper for advice.

As associate director of Vanderbilt University's Curb Center for Art, Enterprise and Public Policy, Tepper thought the center's new building a fitting venue to honor his late friend's legacy. Carter's daughters agreed.

After four days of rooting around the house, Tepper, Stone and Carter selected the 85 pieces that will be unveiled in March as the "Selected Works From the Allen Carter Collection."

"What's exciting about this moment is that we've got essentially a Matisse or a Picasso," Tepper says. "But people have a chance to discover him on their terms."

Eighty-five pieces down, only thousands to go. Stone and Carter have moved the rest of the collection to Hampton Roads so they can catalogue each object at their own pace.

"We're taking it one day at a time," says Stone, sounding very much like her father's daughter.

Printed in The Washington Post Magazine, c2010.

*******************************************

Compulsive Painter Defied Stylistic Trends

By Matt Schudel

Washington Post Staff Writer

Sunday, January 11, 2009; C07

Allen D. "Big Al" Carter, an immensely productive artist who defied stylistic trends and commercial expectations to pursue his singular vision on no one's terms but his own, died Dec. 18 of complications from diabetes at Virginia Hospital Center. He was 61 and lived in Alexandria.

Mr. Carter had exhibited his works widely since the 1970s, often receiving ecstatic reviews from critics, but he was never fully comfortable with the world of art galleries and patrons. Instead, he spent 30 years teaching in alternative schools in Arlington County while compulsively drawing and painting at home.

His work is in the permanent collection of the Corcoran Gallery of Art and, during the past three years, was featured in museum exhibitions in North Carolina and Minnesota. He was also a photographer early in his career, and his photographs of elderly relatives in rural Virginia were featured at the Alexandria Black History Museum in 2007.

Mr. Carter sold some of his artwork to friends and collectors, but he was reluctant to part with much of it. Working feverishly at all hours of the day and night, he amassed a cache of thousands of paintings, drawings and collages that varied from wall-size murals to miniature watercolors that could fit in the palm of his hand. Most of his art has never been seen in public.

"He is a particular type of Washington artist," Mary Battiata wrote in The Washington Post Magazine in 2006, "someone who was understood by peers to have the promise to make it in New York, but who for one reason or another -- temperament, taste, fear, arrogance or some combination -- decided to stay here and fashion a different, quieter career and life."

Mr. Carter stood 6 feet 3 inches, weighed 340 pounds and possessed a gregarious, larger-than-life personality that made him an unforgettable character to many who knew him. He was known to one and all -- including himself -- as "Big Al" or just "Big."

He was sometimes perceived as an unschooled "outsider" artist, but in fact he had a solid education in art history and technique.

"Carter's art is protean, large-hearted, never prissy," Washington Post critic Paul Richard wrote of a 1985 exhibition at a local gallery. "Warmth pours from the walls. To walk into the gallery is to accept Big Al's embrace."

A 1990 New York Times review said his paintings "suggest boundless, uncontrollable freedom . . . [a] complex world of reality, dream and art."

Despite such acclaim, Mr. Carter did not allow his artwork to be shown in the country's art capital, New York, where he could have found greater renown and remuneration. He thought the commissions charged by art galleries were too high and broke with his longtime Washington gallery more than five years ago.

Much to the annoyance of curators and collectors, Mr. Carter did not date his paintings and offered only vague hints at when they were made. He painted on canvas, TV trays, lampshades, boat rudders and home-movie screens, and incorporated musical instruments, brushes, wood and other objects into works. He often used house paint and rummaged through trash bins behind art stores for half-used tubes of oil and acrylic paint.

He marched freely across the borderlines of artistic styles, combining abstraction and swirls of pure energy with recognizable landscapes and portraits. His strong lines reminded some viewers of modern-art pioneer Georges Rouault. Other critics likened his multimedia constructions to those of Robert Rauschenberg, but Mr. Carter thought such comparisons slighted his originality.

He often depicted themes from African American life and was exhibited alongside such renowned black artists as Romare Bearden, but Mr. Carter resisted racial labels and preferred to be called simply an "American artist."

His work sometimes featured animals, nudes, pop culture images or topical references to veterans and warfare. He also had an unexhibited series of 50 paintings based on the Holocaust.

"I paint poor and rich people and their relationships in this society," he told the Virginian-Pilot newspaper in 1997. "I paint the hungry, the homeless, war veterans, children, the powerful and the powerless. I depict pain, joy, contradictions, hope and despair."

Allen Dester Carter was born June 29, 1947, in Washington and grew up in Arlington. His parents had a church in Gainesville that Mr. Carter attended three times a week. He played football at Wakefield High School but was devoted to art from an early age, despite his parents' misgivings. In case he awoke in the middle of the night with an urge to draw, he kept sheets of paper beside his bed.

"I couldn't stop drawing," he told The Post three years ago. "Anything that was white I had to draw on it."

His only prolonged absence from the Washington region came when he moved to Ohio to attend the Columbus College of Art and Design, from which he graduated in 1970. He returned to Northern Virginia and taught at three centers for continuing and alternative education in Arlington County. In the 1990s, he moved to Fredericksburg and loaded freight trucks for a few years before moving to Alexandria and returning to his old teaching job. He retired in 2007.

At the end of his teaching day, Mr. Carter returned to his cramped house to take up his brush. He painted with astonishing speed and sometimes completed a large canvas in less than an hour. In 1982, he painted a 10-by-25-foot mural on a building on Seventh Street NW in two days.

Mr. Carter spent most of his life near Washington and did not like to travel far, except to catch fish or hunt deer with a bow and arrow. He went only as far as he could go by foot or in his undependable van. He refused to board a train, airplane or boat.

"All these things add up to an artist who was driven by his internal compass," said Steven Tepper, a Vanderbilt University official who had known Mr. Carter since the early 1990s. "We all wonder what a true artist is like. Once you meet him, you have the answer to that question."

Mr. Carter's marriage to Mae I. Carter ended in divorce.

Survivors include two daughters, Flora Stone and Cecilia Carter, both of Newport News; a sister, Shirley Chestnut of Alexandria; a brother, Alford Carter of Manassas; and two granddaughters.

"I've never been to Paris or any of those places," Mr. Carter told The Post in 1984, "but all you've got to do is just set up and paint. Art just comes naturally. You just put it down on paper. You've got to keep rolling -- just keep on rolling."

Big Al Carter’s paintings are larger than life in size and power and scope – an equal to the artist’s personality and to his reputation as a painter’s painter and to his career as a distinguished teacher and mentor to young artists.

****************************************

He was an Artist and Teacher, and is survived by two daughters, Flora Stone and her husband, Jerome and Cecilia Carter; two grandchildren, Kayla & Natalie Stone; sister and brother-in-law, Shirley & Levon Chestnut; brother and sister-in-law, Alford & Alice Carter; two aunts, Luvenia Taylor & Louise Johnson; his former wife, Mae Carter, and other relatives.

Interment followed funeral services conducted at the Antioch Church of Christ, Alexandria, VA, Saturday, December 27, 2008.

********************************************

Whatever Happened To ... artist Big Al Carter?

By Kris Coronado

Sunday, January 31, 2010

Allen "Big Al" Carter painted by the numbers -- big numbers. Three floors of the artist's Alexandria home were crammed floor to ceiling with his life's work. When profiled by The Washington Post Magazine in May 2006, Carter estimated he had 20,000 pieces -- from intricate etchings to enormous day-glo paintings -- in the 900-square-foot space. "His creative impulse was everywhere," says longtime friend Steven Tepper, 42.

Carter, 61, died of complications from diabetes on Dec. 18, 2008, leaving his daughters, Flora Stone, 35, and Cecilia Carter, 29, facing a challenge: what to do with all that art.

Despite the extent of his talent, Carter had shied away from the wheeling and dealing of the art scene. While he'd sometimes lend pieces for temporary gallery installations, he didn't avidly pursue the limelight and was reluctant to sell his compositions.

Art speculators contacted Carter's daughters as early as the weekend of his death. "I was, like, 'Uh, no,' " Stone says. "We weren't interested in selling his work. We were looking toward promoting him, as if he's still here."

Easy enough: All she and her sister had to do was sift through an avalanche of art in their free time (Stone works at Hampton University, and Carter is an undergrad at Thomas Nelson Community College). The sisters turned to Tepper for advice.

As associate director of Vanderbilt University's Curb Center for Art, Enterprise and Public Policy, Tepper thought the center's new building a fitting venue to honor his late friend's legacy. Carter's daughters agreed.

After four days of rooting around the house, Tepper, Stone and Carter selected the 85 pieces that will be unveiled in March as the "Selected Works From the Allen Carter Collection."

"What's exciting about this moment is that we've got essentially a Matisse or a Picasso," Tepper says. "But people have a chance to discover him on their terms."

Eighty-five pieces down, only thousands to go. Stone and Carter have moved the rest of the collection to Hampton Roads so they can catalogue each object at their own pace.

"We're taking it one day at a time," says Stone, sounding very much like her father's daughter.

Printed in The Washington Post Magazine, c2010.

*******************************************

Compulsive Painter Defied Stylistic Trends

By Matt Schudel

Washington Post Staff Writer

Sunday, January 11, 2009; C07

Allen D. "Big Al" Carter, an immensely productive artist who defied stylistic trends and commercial expectations to pursue his singular vision on no one's terms but his own, died Dec. 18 of complications from diabetes at Virginia Hospital Center. He was 61 and lived in Alexandria.

Mr. Carter had exhibited his works widely since the 1970s, often receiving ecstatic reviews from critics, but he was never fully comfortable with the world of art galleries and patrons. Instead, he spent 30 years teaching in alternative schools in Arlington County while compulsively drawing and painting at home.

His work is in the permanent collection of the Corcoran Gallery of Art and, during the past three years, was featured in museum exhibitions in North Carolina and Minnesota. He was also a photographer early in his career, and his photographs of elderly relatives in rural Virginia were featured at the Alexandria Black History Museum in 2007.

Mr. Carter sold some of his artwork to friends and collectors, but he was reluctant to part with much of it. Working feverishly at all hours of the day and night, he amassed a cache of thousands of paintings, drawings and collages that varied from wall-size murals to miniature watercolors that could fit in the palm of his hand. Most of his art has never been seen in public.

"He is a particular type of Washington artist," Mary Battiata wrote in The Washington Post Magazine in 2006, "someone who was understood by peers to have the promise to make it in New York, but who for one reason or another -- temperament, taste, fear, arrogance or some combination -- decided to stay here and fashion a different, quieter career and life."

Mr. Carter stood 6 feet 3 inches, weighed 340 pounds and possessed a gregarious, larger-than-life personality that made him an unforgettable character to many who knew him. He was known to one and all -- including himself -- as "Big Al" or just "Big."

He was sometimes perceived as an unschooled "outsider" artist, but in fact he had a solid education in art history and technique.

"Carter's art is protean, large-hearted, never prissy," Washington Post critic Paul Richard wrote of a 1985 exhibition at a local gallery. "Warmth pours from the walls. To walk into the gallery is to accept Big Al's embrace."

A 1990 New York Times review said his paintings "suggest boundless, uncontrollable freedom . . . [a] complex world of reality, dream and art."

Despite such acclaim, Mr. Carter did not allow his artwork to be shown in the country's art capital, New York, where he could have found greater renown and remuneration. He thought the commissions charged by art galleries were too high and broke with his longtime Washington gallery more than five years ago.

Much to the annoyance of curators and collectors, Mr. Carter did not date his paintings and offered only vague hints at when they were made. He painted on canvas, TV trays, lampshades, boat rudders and home-movie screens, and incorporated musical instruments, brushes, wood and other objects into works. He often used house paint and rummaged through trash bins behind art stores for half-used tubes of oil and acrylic paint.

He marched freely across the borderlines of artistic styles, combining abstraction and swirls of pure energy with recognizable landscapes and portraits. His strong lines reminded some viewers of modern-art pioneer Georges Rouault. Other critics likened his multimedia constructions to those of Robert Rauschenberg, but Mr. Carter thought such comparisons slighted his originality.

He often depicted themes from African American life and was exhibited alongside such renowned black artists as Romare Bearden, but Mr. Carter resisted racial labels and preferred to be called simply an "American artist."

His work sometimes featured animals, nudes, pop culture images or topical references to veterans and warfare. He also had an unexhibited series of 50 paintings based on the Holocaust.

"I paint poor and rich people and their relationships in this society," he told the Virginian-Pilot newspaper in 1997. "I paint the hungry, the homeless, war veterans, children, the powerful and the powerless. I depict pain, joy, contradictions, hope and despair."

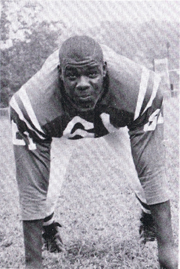

Allen Dester Carter was born June 29, 1947, in Washington and grew up in Arlington. His parents had a church in Gainesville that Mr. Carter attended three times a week. He played football at Wakefield High School but was devoted to art from an early age, despite his parents' misgivings. In case he awoke in the middle of the night with an urge to draw, he kept sheets of paper beside his bed.

"I couldn't stop drawing," he told The Post three years ago. "Anything that was white I had to draw on it."

His only prolonged absence from the Washington region came when he moved to Ohio to attend the Columbus College of Art and Design, from which he graduated in 1970. He returned to Northern Virginia and taught at three centers for continuing and alternative education in Arlington County. In the 1990s, he moved to Fredericksburg and loaded freight trucks for a few years before moving to Alexandria and returning to his old teaching job. He retired in 2007.

At the end of his teaching day, Mr. Carter returned to his cramped house to take up his brush. He painted with astonishing speed and sometimes completed a large canvas in less than an hour. In 1982, he painted a 10-by-25-foot mural on a building on Seventh Street NW in two days.

Mr. Carter spent most of his life near Washington and did not like to travel far, except to catch fish or hunt deer with a bow and arrow. He went only as far as he could go by foot or in his undependable van. He refused to board a train, airplane or boat.

"All these things add up to an artist who was driven by his internal compass," said Steven Tepper, a Vanderbilt University official who had known Mr. Carter since the early 1990s. "We all wonder what a true artist is like. Once you meet him, you have the answer to that question."

Mr. Carter's marriage to Mae I. Carter ended in divorce.

Survivors include two daughters, Flora Stone and Cecilia Carter, both of Newport News; a sister, Shirley Chestnut of Alexandria; a brother, Alford Carter of Manassas; and two granddaughters.

"I've never been to Paris or any of those places," Mr. Carter told The Post in 1984, "but all you've got to do is just set up and paint. Art just comes naturally. You just put it down on paper. You've got to keep rolling -- just keep on rolling."

Big Al Carter’s paintings are larger than life in size and power and scope – an equal to the artist’s personality and to his reputation as a painter’s painter and to his career as a distinguished teacher and mentor to young artists.

****************************************

Inscription

FOREVER IN OUR HEARTS

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

Advertisement