Given the option of serving either in Panama or in the Philippines, he chose the Philippines, which he felt was far enough away from his old neighborhood and his troubled childhood. Richard arrived in Manila's Pier Seven, in the early months of 1940.

His pre-war days in Manila, serving with the 31st Infantry Regiment, were some of the happiest days of his life. He trained to be a soldier in fields just outside the walls of Intramuros. He was billeted in Estado Mayor. His duties included guarding the men in the stockade, guarding the Port Area, and once a week, marching with his company, through Escolta, assuring the merchants their investments were safe, because the US Army was present.

Just prior to the beginning of the hostilities, Richard was transferred to a newly formed unit, the 12th MPs (PS), the only Philippine Scout Unit which had both American and Filipino enlisted men. Their first mission was directing the dense traffic jams of retreating soldiers and refugees into the Bataan peninsula, while Japanese planes strafed and bombed them, uncontested.

When Gen. Edward P. King surrendered his Luzon Force, on Bataan, Richard Gordon was on Mt. Samat, where he became a prisoner of the Japanese. The following day, from the town of Mariveles, he began the "Hike" which over a year later would be called, "The Bataan Death March". On the "Hike", he first witnessed the barbaric cruelties of the Japanese Imperial Army. He arrived in Camp O'Donnell, in Capas, Tarlac, with the others who survived, from his column, dehydrated, starving, and exhausted, stunned by the horrors he had witnessed.

While a prisoner in Camp O'Donnell, Richard worked on those endless burial details, picking up the bodies thrown outside from the camp's sawali barracks, which housed the dying men. He often wondered, when he himself would be buried, as he fell ill while at the camp.

Around June 6, 1942, approximately 45 days later, the Japanese decided to close Camp O'Donnell and move the American POWs to Cabanatuan, in Nueva Ecija. Richard, along with about five hundred other men, stayed behind, in Camp O'Donnell, to finish burying the dead and care for those too sick to make the journey to Cabanatuan. It was at this time he participated in building the "O'Donnell Cross." Instead of giving them food, which they would have preferred, the Japanese gave them cement to build a marker for their dead. Gordon was later moved to Cabanatuan POW Camp.

He only stayed in Cabanatuan briefly, then was selected to go to Japan to work as a slave laborer. Back on Manila's pier #7 again, he boarded an old cargo ship named the Niigata Maru. This was one of the first of a series of vessels referred to as "Hell Ships" which brought men from the Philippines to northern Asia. On these ships, conditions were often worse than they were in Camp O'Donnell.

After about thirty days, crammed into a cargo hold with other men, barely subsisting on the little food and water given to them, Maj. Gordon arrived in Moji, Japan. From Moji, he was sent to Mitsushima, in the Nagano Prefecture. There he worked, as a slave laborer, for three years building a hydro-electric dam, which is still in use today.

After the war, Richard decided to make the US Army his career, but this time as a commissioned officer. He did tours of duty in Europe and, during the Korean War, in Okinawa. It was also at this time that he, first, married and started a family.

Maj. Gordon retired from the military and joined a police force in Long Island, New York. In this phase of his life, he began, arduously, researching the Defense of Bataan and the WW II POW experience in Asia. He read everything he could get his hands on, books, articles, and documents, all the time, referring back to his experiences to verify their validity. He made himself one of the most knowledgeable men on the history of Bataan and the POW experience in Asia. He attended Bataan and POW veteran's meetings and conventions to further learn and discuss what he had researched.

This long (over twenty years) process of research culminated with Maj. Gordon finishing his book: "Horyo." This book covers his life growing up in New York City and life in pre-war Manila. He then integrates it with his life as a soldier on Bataan and his days as a Horyo, a prisoner of the Japanese. He unabashedly describes the horrors of life on Bataan, the nightmare of the Bataan Death March, and the dehumanization of his fellow POWs in the prison camps. The book ends with him learning to live his life again, after the war and coping with the physical problems, and the emotional scars he had to reconcile. Horyo was one of the first books to mention the sacrifices made by Filipino soldiers on the battlefields of Bataan and on the Death March, and Camp O'Donnell.

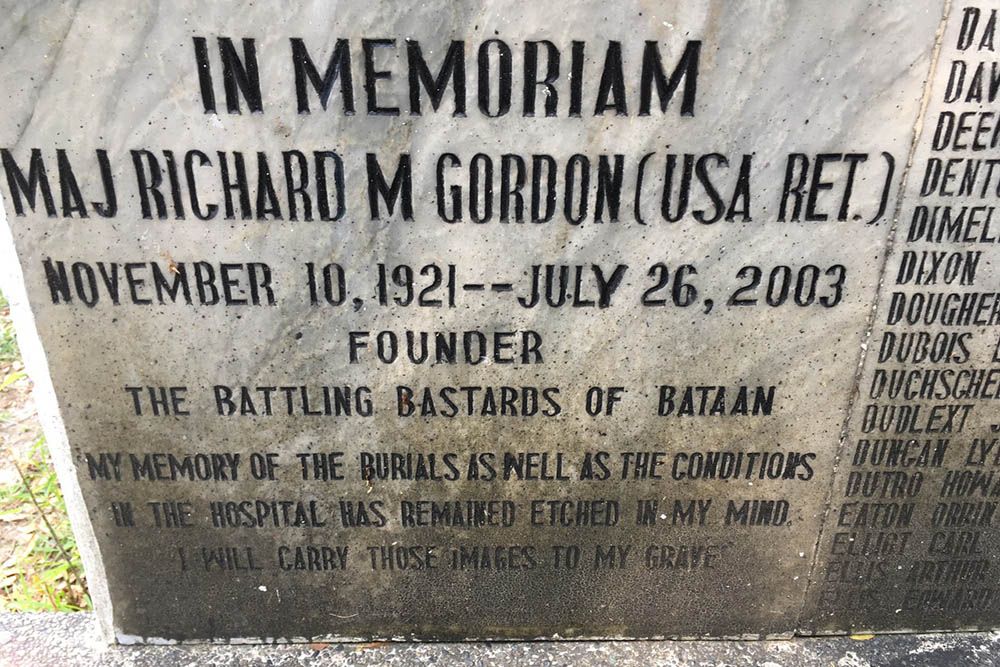

For many years, the main POW organizations were the American X-POWs (formerly the Bataan Relief Association), the American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor, and the New Mexico Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor. Around 1992, Maj. Gordon and other Bataan veterans created the organization, "The Battling Bastards of Bataan." It's board of directors included authors and Bataan veterans. Not surprisingly, it also included a Filipino historian and University professor. The organization survived it's early years through Maj. Gordon's strong will and tenacity, as it was surrounded by much larger and richer organizations. The motto of "The Battling Bastards of Bataan" is simply, "The Pursuit of Truth!" The organization's mission is to leave behind for future generations the true history of the Filipinos and Americans who defended the Bataan peninsula in 1942.

Maj. Gordon and other BBB members worked (and still do) one on one with next of kin of Bataan veterans who did not survive the war to try as best as possible to explain to them the circumstances of their relatives death, and to try to find a surviving veteran who knew their relative when they were still alive. Maj. Gordon worked with teachers and professors at every level. He also worked with historians wishing to write a books about Bataan and with film makers wishing to produce film documentaries on Bataan and the POWs of Asia. Most books and film documentaries about Bataan list Maj. Gordon as a contributor to the project in their acknowledgement pages or on the film credits. Maj. Gordon became one of the main sources for Bataan and POW history.

Through Maj. Gordon's leadership, three monuments were built in the Philippines. The BBB contributed in building the Wainwright monument on Corregidor. In Limay/Lamao, Bataan, the BBB built the monument for Gen. King, the man who led them in battle and in their surrender. On the grounds of the Capas National Shrine, the BBB built a large monument to honor the Americans who died in Camp O'Donnell. The monument consist of an exact replica of the original "O'Donnell Cross" and a marble wall on which are chiseled the names of all the men who died in Camp O'Donnell.

In the past ten years, Maj. Gordon has dedicated much of his time bringing Filipino and American Bataan veterans together. He has led several trips back to the Philippines, bringing with him American Bataan veterans to meet with their Filipino "Comrade at Arms." In the year 2000, Maj. Gordon went to Camp Aguinaldo, in Makati, and met with the leaders of the "Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor." In a very private and solemn ceremony, he traded organization hats with Col. Rafael Estrada, the commander of the DBC. Present were two of the Philippines' most valiant Bataan heroes: Gen. Luis Villa-Real and Gen. Francisco Adriano.

In 2002, there was another BBB trip back to the Philippines. Maj. Gordon brought back with him one of the largest Bataan related contingents of Americans to ever travel together to the Philippines. The American veterans on the tour were taken to the headquarters of the Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor, in Camp Aguinaldo, for a ceremony in which the American veterans were inducted into the DBC.

Under Maj. Gordon's direction, the Battling Bastards of Bataan worked for "Equity for Filipino Veterans." The BBB is worked with various Filipino veteran organizations in the United States. Maj. Gordon was one of the first, if not the first Bataan veterans to publicly acknowledge the role of Filipino veterans on Bataan. He often said, "Remember, the Filipinos did most of the fighting and dying on Bataan."

For at least two generations, Filipinos and Americans shared the same history. The defense of the Bataan peninsula was that "shared" history's most noble epoch. Maj. Richard M. Gordon exemplified that epoch. He did so when he was young, in his pre-war days in Manila. He did so as a soldier, huddled in those trenches on Bataan, and during the Death March, when he first learned about the inhumanity of war. He continued to exemplify that shared history, as he tirelessly worked to leave behind the true history of the Filipino and Americans who made the ultimate sacrifice on that peninsula. He crossed barriers to reunite the Filipino and American defenders, and as he supported equity and justice for Filipino veterans.

Maj. Gordon quietly passed away on July 26, 2003, at 4:25 AM, in Schenectady, New York. He will not be forgotten, by those whose lives he touched. Funeral services were held on September 12, 2003, at Arlington National Cemetery. Send all letters of condolences and cards to Lyn Gordon, at 10 North Church St., Schenectady, NY 12305.

Given the option of serving either in Panama or in the Philippines, he chose the Philippines, which he felt was far enough away from his old neighborhood and his troubled childhood. Richard arrived in Manila's Pier Seven, in the early months of 1940.

His pre-war days in Manila, serving with the 31st Infantry Regiment, were some of the happiest days of his life. He trained to be a soldier in fields just outside the walls of Intramuros. He was billeted in Estado Mayor. His duties included guarding the men in the stockade, guarding the Port Area, and once a week, marching with his company, through Escolta, assuring the merchants their investments were safe, because the US Army was present.

Just prior to the beginning of the hostilities, Richard was transferred to a newly formed unit, the 12th MPs (PS), the only Philippine Scout Unit which had both American and Filipino enlisted men. Their first mission was directing the dense traffic jams of retreating soldiers and refugees into the Bataan peninsula, while Japanese planes strafed and bombed them, uncontested.

When Gen. Edward P. King surrendered his Luzon Force, on Bataan, Richard Gordon was on Mt. Samat, where he became a prisoner of the Japanese. The following day, from the town of Mariveles, he began the "Hike" which over a year later would be called, "The Bataan Death March". On the "Hike", he first witnessed the barbaric cruelties of the Japanese Imperial Army. He arrived in Camp O'Donnell, in Capas, Tarlac, with the others who survived, from his column, dehydrated, starving, and exhausted, stunned by the horrors he had witnessed.

While a prisoner in Camp O'Donnell, Richard worked on those endless burial details, picking up the bodies thrown outside from the camp's sawali barracks, which housed the dying men. He often wondered, when he himself would be buried, as he fell ill while at the camp.

Around June 6, 1942, approximately 45 days later, the Japanese decided to close Camp O'Donnell and move the American POWs to Cabanatuan, in Nueva Ecija. Richard, along with about five hundred other men, stayed behind, in Camp O'Donnell, to finish burying the dead and care for those too sick to make the journey to Cabanatuan. It was at this time he participated in building the "O'Donnell Cross." Instead of giving them food, which they would have preferred, the Japanese gave them cement to build a marker for their dead. Gordon was later moved to Cabanatuan POW Camp.

He only stayed in Cabanatuan briefly, then was selected to go to Japan to work as a slave laborer. Back on Manila's pier #7 again, he boarded an old cargo ship named the Niigata Maru. This was one of the first of a series of vessels referred to as "Hell Ships" which brought men from the Philippines to northern Asia. On these ships, conditions were often worse than they were in Camp O'Donnell.

After about thirty days, crammed into a cargo hold with other men, barely subsisting on the little food and water given to them, Maj. Gordon arrived in Moji, Japan. From Moji, he was sent to Mitsushima, in the Nagano Prefecture. There he worked, as a slave laborer, for three years building a hydro-electric dam, which is still in use today.

After the war, Richard decided to make the US Army his career, but this time as a commissioned officer. He did tours of duty in Europe and, during the Korean War, in Okinawa. It was also at this time that he, first, married and started a family.

Maj. Gordon retired from the military and joined a police force in Long Island, New York. In this phase of his life, he began, arduously, researching the Defense of Bataan and the WW II POW experience in Asia. He read everything he could get his hands on, books, articles, and documents, all the time, referring back to his experiences to verify their validity. He made himself one of the most knowledgeable men on the history of Bataan and the POW experience in Asia. He attended Bataan and POW veteran's meetings and conventions to further learn and discuss what he had researched.

This long (over twenty years) process of research culminated with Maj. Gordon finishing his book: "Horyo." This book covers his life growing up in New York City and life in pre-war Manila. He then integrates it with his life as a soldier on Bataan and his days as a Horyo, a prisoner of the Japanese. He unabashedly describes the horrors of life on Bataan, the nightmare of the Bataan Death March, and the dehumanization of his fellow POWs in the prison camps. The book ends with him learning to live his life again, after the war and coping with the physical problems, and the emotional scars he had to reconcile. Horyo was one of the first books to mention the sacrifices made by Filipino soldiers on the battlefields of Bataan and on the Death March, and Camp O'Donnell.

For many years, the main POW organizations were the American X-POWs (formerly the Bataan Relief Association), the American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor, and the New Mexico Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor. Around 1992, Maj. Gordon and other Bataan veterans created the organization, "The Battling Bastards of Bataan." It's board of directors included authors and Bataan veterans. Not surprisingly, it also included a Filipino historian and University professor. The organization survived it's early years through Maj. Gordon's strong will and tenacity, as it was surrounded by much larger and richer organizations. The motto of "The Battling Bastards of Bataan" is simply, "The Pursuit of Truth!" The organization's mission is to leave behind for future generations the true history of the Filipinos and Americans who defended the Bataan peninsula in 1942.

Maj. Gordon and other BBB members worked (and still do) one on one with next of kin of Bataan veterans who did not survive the war to try as best as possible to explain to them the circumstances of their relatives death, and to try to find a surviving veteran who knew their relative when they were still alive. Maj. Gordon worked with teachers and professors at every level. He also worked with historians wishing to write a books about Bataan and with film makers wishing to produce film documentaries on Bataan and the POWs of Asia. Most books and film documentaries about Bataan list Maj. Gordon as a contributor to the project in their acknowledgement pages or on the film credits. Maj. Gordon became one of the main sources for Bataan and POW history.

Through Maj. Gordon's leadership, three monuments were built in the Philippines. The BBB contributed in building the Wainwright monument on Corregidor. In Limay/Lamao, Bataan, the BBB built the monument for Gen. King, the man who led them in battle and in their surrender. On the grounds of the Capas National Shrine, the BBB built a large monument to honor the Americans who died in Camp O'Donnell. The monument consist of an exact replica of the original "O'Donnell Cross" and a marble wall on which are chiseled the names of all the men who died in Camp O'Donnell.

In the past ten years, Maj. Gordon has dedicated much of his time bringing Filipino and American Bataan veterans together. He has led several trips back to the Philippines, bringing with him American Bataan veterans to meet with their Filipino "Comrade at Arms." In the year 2000, Maj. Gordon went to Camp Aguinaldo, in Makati, and met with the leaders of the "Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor." In a very private and solemn ceremony, he traded organization hats with Col. Rafael Estrada, the commander of the DBC. Present were two of the Philippines' most valiant Bataan heroes: Gen. Luis Villa-Real and Gen. Francisco Adriano.

In 2002, there was another BBB trip back to the Philippines. Maj. Gordon brought back with him one of the largest Bataan related contingents of Americans to ever travel together to the Philippines. The American veterans on the tour were taken to the headquarters of the Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor, in Camp Aguinaldo, for a ceremony in which the American veterans were inducted into the DBC.

Under Maj. Gordon's direction, the Battling Bastards of Bataan worked for "Equity for Filipino Veterans." The BBB is worked with various Filipino veteran organizations in the United States. Maj. Gordon was one of the first, if not the first Bataan veterans to publicly acknowledge the role of Filipino veterans on Bataan. He often said, "Remember, the Filipinos did most of the fighting and dying on Bataan."

For at least two generations, Filipinos and Americans shared the same history. The defense of the Bataan peninsula was that "shared" history's most noble epoch. Maj. Richard M. Gordon exemplified that epoch. He did so when he was young, in his pre-war days in Manila. He did so as a soldier, huddled in those trenches on Bataan, and during the Death March, when he first learned about the inhumanity of war. He continued to exemplify that shared history, as he tirelessly worked to leave behind the true history of the Filipino and Americans who made the ultimate sacrifice on that peninsula. He crossed barriers to reunite the Filipino and American defenders, and as he supported equity and justice for Filipino veterans.

Maj. Gordon quietly passed away on July 26, 2003, at 4:25 AM, in Schenectady, New York. He will not be forgotten, by those whose lives he touched. Funeral services were held on September 12, 2003, at Arlington National Cemetery. Send all letters of condolences and cards to Lyn Gordon, at 10 North Church St., Schenectady, NY 12305.

Gravesite Details

MAJ US ARMY; WORLD WAR II; KOREA

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement