SURGET. He attended Harvard College and graduated with a B. A. degreee in Law

(Class of 1812). The year he graduated, he secretly married Julia Maria MURRAY,

daughter of Rev. John MURRAY (a reknowned Universalist minister) and Judith

SARGENT (a reknowned poet, author, and early women's rights activist).

Adam and Julia had 2 children: Charlotte (who died young) and Adam Lewis

BINGAMAN, Jr. Julia died shortly thereafter.

After Julia's death, Adam entered into a relationship with Mary Ellen WILLIAMS,

a free black. She died in Natchez, MS in 1861.

Adam and Mary had at least six children together: Frances Ann BINGAMAN/WILLIAMS

(wife of the reknowned horse trainer, John Benjamin PRYOR), Cordelia

BINGAMAN/WILLIAMS, Emilie BINGAMAN/WILLIAMS, Marie Sophie Charlotte

BINGAMAN/WILLIAMS, James Adam BINGAMAN/WILLIAMS (who was a casualty of the

Steamboat Fashion disaster, Dec. 1867) and Henriette BINGAMAN/WILLIAMS.

Adam was a prominent planter, and was a third-generation owner of the Fatherland

Plantation near Natchez, in Adams Co., MS.

Adam was one of the principle founders and owners of the Metairie Race Course,

which was later abandoned and redeveloped as the Metairie Cemetery.

Adam was an avid horseman, and at one time owned "Lexington", a famous racehorse

of the era. John Benjamin PRYOR (who later became his son-in-law), was a

reknowed horse trainer who trained and cared for Lexington (among other quality

racehorses). Mr. PRYOR also served as Adam's overseer of the Fatherland

Plantation.

Adam was a talented orator and politician. He served as a member of the

Mississippi House of Representatives (1833) and as President of the Mississippi

State Senate (1838-1840). In the latter capacity, he was privileged to give a

speach before Gen. Andrew Jackson (1840). He also served on the select

committee during the Nullification Crisis, one of the important historical

events which preceeded and eventually led up to the outbreak of the Civil War.

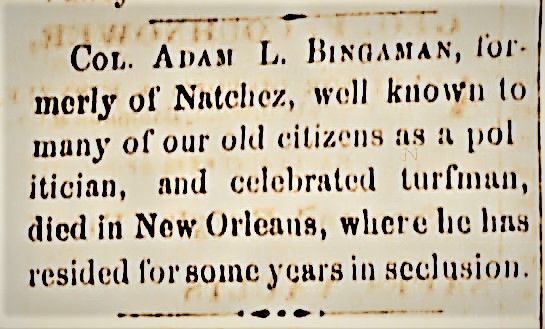

THE OUACHITA TELEGRAPH — Monroe, Ouachita Parish, LA

Saturday, 19 May 1883 (p. 1, col. 2-3)

ADAM L. BINGAMAN.

--------------------

By Hon. J. F. H. Claiborne.

--------------------

[From Moynier’s Louisiana Biographies.]

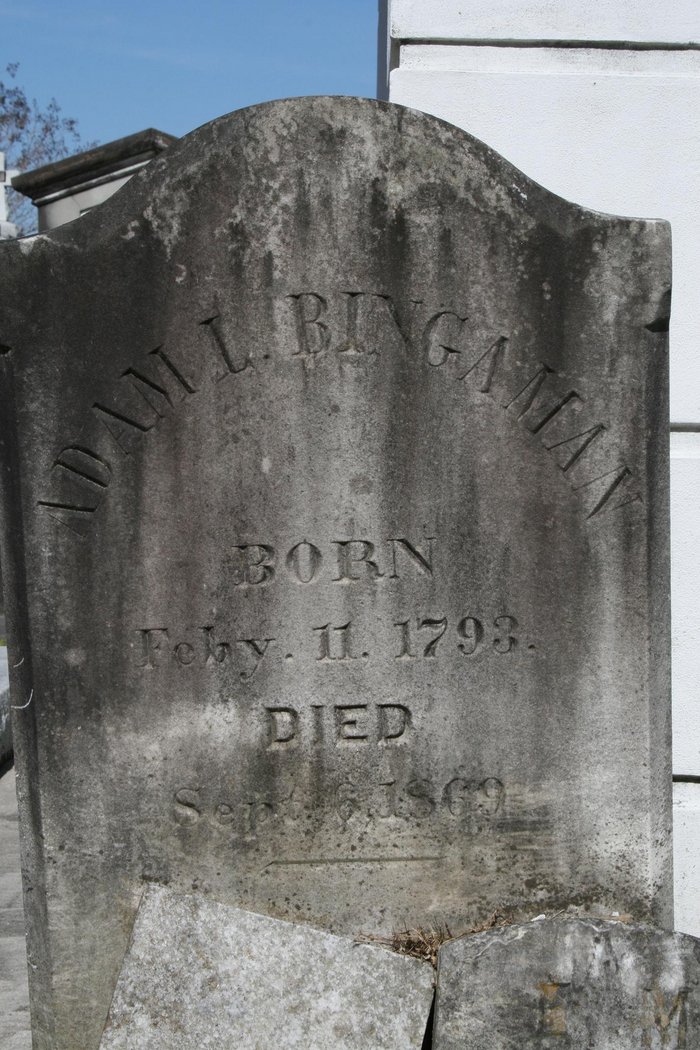

This distinguished gentleman, once a leader in the highest social circles of Louisiana and Mississippi, was born near Bayou Sara, February 11, 1793. His family were of German extraction, and obtained large grants from the Spanish authorities. “Fatherland,” on St. Catherines, near Natchez, became their chief residence, and there they accumulated great wealth.

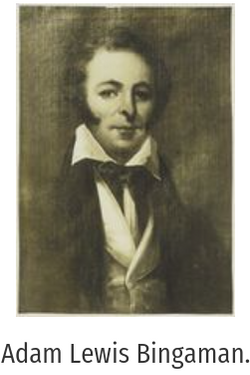

Adam L. Bingaman was educated at Harvard, and contested the first honor with Edward Everett. On his return he found himself master of an extensive plantation and many slaves. He gave himself up to its management and its attractions. He became a successful planter, a star of fashion, a social favorite, and a devotee of the turf. Endowed with a personal magnetism that attracted everyone, he soon secured a large following, and became the idol of the multitude. But for the fatal heritage of wealth and slaves, he would, doubtless, have become the foremost man in the Southwest. His person was imposing and elegant; his features classic and expressive; his manners seductive; his voice musical and sonorous; his imagination vivid; in fine, he had all the highest attributes of the orator, with the classical resources of the scholar.

Like most Southern men of education and talents, he was ambitious of political distinction. He often served in the Legislature with marked ability, and was the leader of any party or any measure he espoused. But, though he made many efforts, he always failed to secure high position. His passion for the turf, and its incidentals, and his political opinions, which he was too honest to compromise, were the drawbacks. He based his political creed on the doctrines of Henry Clay, and was, under all reverses, devoted to that illustrious statesman. This was enough to keep Col. Bingaman in a minority in Mississippi. There were memorable when, had he changed or even modified his opinion or tempered his tone, or, held himself “open to conviction,” he might have vaulted into the highest positions. He was often advised, solicited and pressed to do so by political opponents; but he clung with inflexible honesty to his convictions, and saw very inferior and more pliant colleagues monopolize the honors.

When South Carolina enacted her ordinance of nullification and courted antagonism with Andrew Jackson, President of the United States, Col. Bingaman sided with the Government in defence of the Union, but would go no farther.

In some vital measures of State policy—such as the representation of the new Chickasaw counties, which Mr. Prentiss and the Whigs generally opposed—he co-operated with the Democrats, and would have been welcomed as their leader; but he persistently refused to support their Presidential nominees.

Before the civil war he had become financially embarrassed, from promiscuous indorsements in an era of rotten banks and insane speculation, and the unhappy and ever-to-be-deplored conflict, and the changes that ensued, completed his ruin.

He had, some years previously, surrendered his hereditary estate, and made his residence in a humble domicile in an obscure quarter of your city [i.e., New Orleans].

I met him a few weeks before his death, and he told me [that he] had been compelled to part with his books. He referred to them in tremulous accents and with tearful eyes, as men refer to the loved and lost. One volume of the Greek tragedies and the Horace he had used at Harvard were found under his pillow when he died!

He was familiar with the classics; read them daily, declaimed the finest passages, and would often imitate the accent, intonation and manner of the most eminent persons and graduates of Harvard. I shall never forget the wealth of scholarship he displayed at a dinner party in honor of Edward Everett by the late Dr. Sam Davis, of Natchez, one of our richest planters. The company consisted of eminent lawyers, physicians and divines who had been educated at Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and William and Mary, in Virginia. I was the junior guest, because, although very young, I was known as the friend and correspondent of Alexander Everett, a scholar not inferior to his more illustrious brother.

Of course it was the business of the evening to draw out the distinguished guest. Mrs. Davis was a lady of imperial presence, with rare conversational and musical gifts. She was the daughter of the last of the Spanish Governors of Natchez. When the superb service of plate appeared with the dessert, emblazoned with the arms and heraldic devices of her ancestors, Mr. Everett drifted into Spanish literature, and held the table enrapt by the modulated sweetness of his tones and the spell of his inspiration. Mrs. Davis and Col. Bingaman, by an occasional question or suggestion, continued to draw him from Spain into Italy, and he recited some passages from the great masters with thrilling eloquence. It was 10 p. m. before the ladies left the table. Mr. Davis introduced some cobwebbed bottles of South Side Madeira, that had been imported by Mr. Bingham, the great merchant of Philadelphia, during Washington’s administration. We all knew that his daughter had married Mr. Baring, afterwards Lord Ashburton, who had negotiated with Mr. Webster the northeastern boundary controversy, and thus averted a menacing issue between two great kindred nations. The wine, of course, was delicious, apart from its historical associations, and I must say Mr. Everett inhaled its aroma and imbibed it with the air of a connoisseur. After two or three glasses, he grew still more fascinating, and the warm, sunny tints of the generous fluid colored his thoughts and his language. As the clock struck one, he rose and recited in Spanish, Sancho Panza’s eulogy on sleep.

Col. Bingaman then addressed him in a dialect not understood by any at the table but Mr. Davis and myself—the Choctaw—a language musical and resonant as the ancient Greek:

“Mingo of the Massachusetts, farewell! Return to the wigwams of your fathers, where the mighty waters roll their billows, and the voice of the Great Spirit thunders along the shore. Tell them that you have seen the Great River, and that in every hamlet and village and city on its banks you have found warriors of the Massachusetts tribe, wedded to the daughters of the land, prosperous and happy, and everywhere a people true to the traditions of their fathers, and cherishing their ashes.

“Sachem! May sunshine light your path, and peace go with you to your own hunting grounds.”

The man who uttered these eloquent words in tones that magnetized the brilliant orator from Boston, and all who were present—the most gifted son of Mississippi—died almost without an attendant, was buried without a mourner, and now sleeps in an obscure grave in a chilling and dreary cemetery in New Orleans. His ashes should be transferred to the historic city he loved so well, which stands amidst the tumuli and monuments of buried nations.

INFORMATION SOURCE: Kevin Bingaman, Find A Grave member

UPDATED INFORMATION REGARDING THE CHILDREN OF ADAM LEWIS BINGAMAN:

Courtesy of Debbie Mullin, a direct descendant and fellow genealogist, together with additional complementary data from other reliable sources.

Adam Lewis BINGAMAN (1793-1869) and his wife Julia MURRAY (d. by 1824) were the parents of:

Charlotte BINGAMAN (1813-1820)

Adam Lewis BINGAMAN, Jr., husb. of Miss LIVINGSTON

Following the death of his wife Julia, Adam united with Amelia (1805-1841), who was of African-American heritage. Adam & Amelia were not legally married because inter-racial marriages were not generally permitted by MS/LA state law at that time. Their children were:

Frances Ann BINGAMAN (bc. 1826), wife of John B. PRYOR

Cordelia BINGAMAN (c. 1828-1891); Cordelia never married

Amelia (or Emilie) BINGAMAN, wife of Bernard COHEN

John BINGAMAN

Henrietta BINGAMAN

Following the death of Amelia, Adam united with Mary Ellen WILLIAMS (d. 1861). Mary was a free woman of African-American heritage. Adam & Mary were not legally married because inter-racial marriages were not generally permitted by MS/LA state law at that time. Their children were:

Marie Sophie Chatlotte BINGAMAN/WILLIAMS*

James Adam BINGAMAN/WILLIAMS* (a casualty of the Steamboat "Fashion")

Eleanora BINGAMAN/WILLIAMS*

*These children referred to themselves and were generally recognized by others as children of Adam Lewis BINGAMAN (either officially or unofficially), although they were occasionally referred to as being WILLIAMS, following their mother's surname.

SURGET. He attended Harvard College and graduated with a B. A. degreee in Law

(Class of 1812). The year he graduated, he secretly married Julia Maria MURRAY,

daughter of Rev. John MURRAY (a reknowned Universalist minister) and Judith

SARGENT (a reknowned poet, author, and early women's rights activist).

Adam and Julia had 2 children: Charlotte (who died young) and Adam Lewis

BINGAMAN, Jr. Julia died shortly thereafter.

After Julia's death, Adam entered into a relationship with Mary Ellen WILLIAMS,

a free black. She died in Natchez, MS in 1861.

Adam and Mary had at least six children together: Frances Ann BINGAMAN/WILLIAMS

(wife of the reknowned horse trainer, John Benjamin PRYOR), Cordelia

BINGAMAN/WILLIAMS, Emilie BINGAMAN/WILLIAMS, Marie Sophie Charlotte

BINGAMAN/WILLIAMS, James Adam BINGAMAN/WILLIAMS (who was a casualty of the

Steamboat Fashion disaster, Dec. 1867) and Henriette BINGAMAN/WILLIAMS.

Adam was a prominent planter, and was a third-generation owner of the Fatherland

Plantation near Natchez, in Adams Co., MS.

Adam was one of the principle founders and owners of the Metairie Race Course,

which was later abandoned and redeveloped as the Metairie Cemetery.

Adam was an avid horseman, and at one time owned "Lexington", a famous racehorse

of the era. John Benjamin PRYOR (who later became his son-in-law), was a

reknowed horse trainer who trained and cared for Lexington (among other quality

racehorses). Mr. PRYOR also served as Adam's overseer of the Fatherland

Plantation.

Adam was a talented orator and politician. He served as a member of the

Mississippi House of Representatives (1833) and as President of the Mississippi

State Senate (1838-1840). In the latter capacity, he was privileged to give a

speach before Gen. Andrew Jackson (1840). He also served on the select

committee during the Nullification Crisis, one of the important historical

events which preceeded and eventually led up to the outbreak of the Civil War.

THE OUACHITA TELEGRAPH — Monroe, Ouachita Parish, LA

Saturday, 19 May 1883 (p. 1, col. 2-3)

ADAM L. BINGAMAN.

--------------------

By Hon. J. F. H. Claiborne.

--------------------

[From Moynier’s Louisiana Biographies.]

This distinguished gentleman, once a leader in the highest social circles of Louisiana and Mississippi, was born near Bayou Sara, February 11, 1793. His family were of German extraction, and obtained large grants from the Spanish authorities. “Fatherland,” on St. Catherines, near Natchez, became their chief residence, and there they accumulated great wealth.

Adam L. Bingaman was educated at Harvard, and contested the first honor with Edward Everett. On his return he found himself master of an extensive plantation and many slaves. He gave himself up to its management and its attractions. He became a successful planter, a star of fashion, a social favorite, and a devotee of the turf. Endowed with a personal magnetism that attracted everyone, he soon secured a large following, and became the idol of the multitude. But for the fatal heritage of wealth and slaves, he would, doubtless, have become the foremost man in the Southwest. His person was imposing and elegant; his features classic and expressive; his manners seductive; his voice musical and sonorous; his imagination vivid; in fine, he had all the highest attributes of the orator, with the classical resources of the scholar.

Like most Southern men of education and talents, he was ambitious of political distinction. He often served in the Legislature with marked ability, and was the leader of any party or any measure he espoused. But, though he made many efforts, he always failed to secure high position. His passion for the turf, and its incidentals, and his political opinions, which he was too honest to compromise, were the drawbacks. He based his political creed on the doctrines of Henry Clay, and was, under all reverses, devoted to that illustrious statesman. This was enough to keep Col. Bingaman in a minority in Mississippi. There were memorable when, had he changed or even modified his opinion or tempered his tone, or, held himself “open to conviction,” he might have vaulted into the highest positions. He was often advised, solicited and pressed to do so by political opponents; but he clung with inflexible honesty to his convictions, and saw very inferior and more pliant colleagues monopolize the honors.

When South Carolina enacted her ordinance of nullification and courted antagonism with Andrew Jackson, President of the United States, Col. Bingaman sided with the Government in defence of the Union, but would go no farther.

In some vital measures of State policy—such as the representation of the new Chickasaw counties, which Mr. Prentiss and the Whigs generally opposed—he co-operated with the Democrats, and would have been welcomed as their leader; but he persistently refused to support their Presidential nominees.

Before the civil war he had become financially embarrassed, from promiscuous indorsements in an era of rotten banks and insane speculation, and the unhappy and ever-to-be-deplored conflict, and the changes that ensued, completed his ruin.

He had, some years previously, surrendered his hereditary estate, and made his residence in a humble domicile in an obscure quarter of your city [i.e., New Orleans].

I met him a few weeks before his death, and he told me [that he] had been compelled to part with his books. He referred to them in tremulous accents and with tearful eyes, as men refer to the loved and lost. One volume of the Greek tragedies and the Horace he had used at Harvard were found under his pillow when he died!

He was familiar with the classics; read them daily, declaimed the finest passages, and would often imitate the accent, intonation and manner of the most eminent persons and graduates of Harvard. I shall never forget the wealth of scholarship he displayed at a dinner party in honor of Edward Everett by the late Dr. Sam Davis, of Natchez, one of our richest planters. The company consisted of eminent lawyers, physicians and divines who had been educated at Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and William and Mary, in Virginia. I was the junior guest, because, although very young, I was known as the friend and correspondent of Alexander Everett, a scholar not inferior to his more illustrious brother.

Of course it was the business of the evening to draw out the distinguished guest. Mrs. Davis was a lady of imperial presence, with rare conversational and musical gifts. She was the daughter of the last of the Spanish Governors of Natchez. When the superb service of plate appeared with the dessert, emblazoned with the arms and heraldic devices of her ancestors, Mr. Everett drifted into Spanish literature, and held the table enrapt by the modulated sweetness of his tones and the spell of his inspiration. Mrs. Davis and Col. Bingaman, by an occasional question or suggestion, continued to draw him from Spain into Italy, and he recited some passages from the great masters with thrilling eloquence. It was 10 p. m. before the ladies left the table. Mr. Davis introduced some cobwebbed bottles of South Side Madeira, that had been imported by Mr. Bingham, the great merchant of Philadelphia, during Washington’s administration. We all knew that his daughter had married Mr. Baring, afterwards Lord Ashburton, who had negotiated with Mr. Webster the northeastern boundary controversy, and thus averted a menacing issue between two great kindred nations. The wine, of course, was delicious, apart from its historical associations, and I must say Mr. Everett inhaled its aroma and imbibed it with the air of a connoisseur. After two or three glasses, he grew still more fascinating, and the warm, sunny tints of the generous fluid colored his thoughts and his language. As the clock struck one, he rose and recited in Spanish, Sancho Panza’s eulogy on sleep.

Col. Bingaman then addressed him in a dialect not understood by any at the table but Mr. Davis and myself—the Choctaw—a language musical and resonant as the ancient Greek:

“Mingo of the Massachusetts, farewell! Return to the wigwams of your fathers, where the mighty waters roll their billows, and the voice of the Great Spirit thunders along the shore. Tell them that you have seen the Great River, and that in every hamlet and village and city on its banks you have found warriors of the Massachusetts tribe, wedded to the daughters of the land, prosperous and happy, and everywhere a people true to the traditions of their fathers, and cherishing their ashes.

“Sachem! May sunshine light your path, and peace go with you to your own hunting grounds.”

The man who uttered these eloquent words in tones that magnetized the brilliant orator from Boston, and all who were present—the most gifted son of Mississippi—died almost without an attendant, was buried without a mourner, and now sleeps in an obscure grave in a chilling and dreary cemetery in New Orleans. His ashes should be transferred to the historic city he loved so well, which stands amidst the tumuli and monuments of buried nations.

INFORMATION SOURCE: Kevin Bingaman, Find A Grave member

UPDATED INFORMATION REGARDING THE CHILDREN OF ADAM LEWIS BINGAMAN:

Courtesy of Debbie Mullin, a direct descendant and fellow genealogist, together with additional complementary data from other reliable sources.

Adam Lewis BINGAMAN (1793-1869) and his wife Julia MURRAY (d. by 1824) were the parents of:

Charlotte BINGAMAN (1813-1820)

Adam Lewis BINGAMAN, Jr., husb. of Miss LIVINGSTON

Following the death of his wife Julia, Adam united with Amelia (1805-1841), who was of African-American heritage. Adam & Amelia were not legally married because inter-racial marriages were not generally permitted by MS/LA state law at that time. Their children were:

Frances Ann BINGAMAN (bc. 1826), wife of John B. PRYOR

Cordelia BINGAMAN (c. 1828-1891); Cordelia never married

Amelia (or Emilie) BINGAMAN, wife of Bernard COHEN

John BINGAMAN

Henrietta BINGAMAN

Following the death of Amelia, Adam united with Mary Ellen WILLIAMS (d. 1861). Mary was a free woman of African-American heritage. Adam & Mary were not legally married because inter-racial marriages were not generally permitted by MS/LA state law at that time. Their children were:

Marie Sophie Chatlotte BINGAMAN/WILLIAMS*

James Adam BINGAMAN/WILLIAMS* (a casualty of the Steamboat "Fashion")

Eleanora BINGAMAN/WILLIAMS*

*These children referred to themselves and were generally recognized by others as children of Adam Lewis BINGAMAN (either officially or unofficially), although they were occasionally referred to as being WILLIAMS, following their mother's surname.

Family Members

Advertisement

Advertisement