/A her hfe that would particularly interest the public, as it is chiefly

the story of her mental growth, we find that her life has been a par-

ticularly active one in many directions. She has been teacher, traveler,

writer, dramatic reader, lecturer, and has had the experience of a political

campaign, in consequence of the nomination for Superintendent of Schools

of Peoria County, Illinois.

Out of this latter experience she says that she early learned the inval-

uable lesson of the worthlessness of "they say," and that she resolved

never afterwards to be disturbed or grieved by calumny or criticism, so

long as she was conscientiously' doing her best.

Her earliest writings were short stories and sketches for a literary

paper of Peoria, but she discontinued this in a short time, feeling that a

longer preparation was necessary for serious literary work, and that before

doing anything more she ought to know what had already been written,

that she might judge whether she herself had anything worth while to say.

She read and studied incessantly, spai'ing no pains to acquaint herself with

the trend of modern thought. She studied French and German, feeling

that these two languages would give her access to scientific books which

she could not get in English. She varied her experiences in teaching by

changing her locality from time to time, and has taught in the high schools

of Lewiston, 111.; Springfield, Mo.; Ann Arbor, Mich.; Kansas City, Mo.,

and now in St. Louis. Twice she obtained a leave of absence, spending a

year in Scotland and England, and a year in Italy, where the Italian

language and literature were her chief subjects of study.

Her summers are usually spent abroad or in some interesting part of

America. She has traveled all over the British Isles and in France, Bel-

gium, Holland, Germanj', Switzerland, Italy and Spain. She has passed a

summer in New Brunswick and Novia Scotia, and another in the chief

cities of Old Mexico, still another in Honolulu, and several of them on the

Pacific Coast. It is to a summer in Quebec that we owe the setting of the

first part of her recent novel, "Kirstie."

This is one of the most interesting novels that has appeared for many

years. The principal character is a woman of heroic type. The analysis

reminds one forcibly of Jane Eyre. There is a delineation of passionate

love directed and controlled by an unfaltering virtue. The situations are

intensely dramatic. A continuous flow of reflections and comments of a

philosophic nature show the author's deep knowledge of humanity. The

descriptions of the places where the scenes are laid are faithfully and

beautifully portrayed — poetically, too, showing the capacity of a true

artist. This book is of the highest moral tone.

In 1896 Miss Fisher was attracted by the suggestive character of Max

Nordau's Entartung, which had just appeared, and made a translation of it

that was accepted by a prominent New York house on condition that Max

Nordau's consent could be obtained. Miss Fisher wrote to Max Nordau,

who replied that he had just disposed of the right of translation to a London

firm. The immense success of the book, which appeared simultaneously

in every modern European tongue, confirmed Miss Fisher's belief that how-

ever extravagant the book might be in some of its assertions, it had its

message for a generation that was mistaking ijathology for literature.

She says that the book made her feel that health — not disease, and moral-

ity — not debauchery, make the surest soil for sound literary productions.

About this time the "Valiant Woman" to whose memory Miss Fisher's

latest book is a loving tribute, engaged her in a correspondence on English

literature with a young girl of Santa Fe, N. M. Miss Fisher's letters were

read there to a woman's club, and learning of the favor they had received

she was led to submit them to a publisher as an aid to the young in answer-

ing that familiar question, "What shall I read?" They were published

by S. C. Griggs & Co., Chicago, III., whose successors, Scott, Foresman

& Co., still continue to publish thein under the title of "Twenty-five

Letters on English Authors." They are written in an easy, flowing style,

and abound in literary anecdotes and personal glimpses of the great men

and women whose works are the treasures of the English tongue. This

book was followed by "A General Survey of American Literature," pub-

lished by A. C. McCIurg & Co., Chicago.

After the publication of these two books Miss Fisher went to Boston

to avail herself of the advantages of the public library there. She wished

to study the literary criticism of France. For Saint Beuve she had a

profound admiration, and soon discovered that he was but the bright

particular star of a whole constellation of brilliant critics. Finding that

the names of these critics were almost, if not wholly, unknown to English

readers, she wished to share her enthusiasm with the public, and wrote

"A Group of French Critics," in which she gave a brief biographical sketch

of Edmond Scherer, Ernest Bersot, Saint-Marc Girardin, Ximenes Doudan

and Gustave Planche. In addition to the biography, she translated speci-

mens of the pungent criticism of these clever thinkers, hoping that the

sanity of their views might create a public demand for them in America.

The book attracted some good notices from the best reviewers, but the

general public was, and is, extremely indifferent to literary criticism,

and the book is now out of print, the plates having been recently destroyed.

Then Miss Fisher tried her hand at fiction. While in Glasgow,

Scotland, she had seen a good deal of the social work among the poor,

known as "slumming," and was not wholly converted to many of its

methods. She thought that the interest in the poor was rather a fad

among the idle rich than the result of the promptings of sincere sympathy,

and that it is not given to everj^one to act as an inspiration and a guide

to them. This is the theme of "Gertrude Dorrance," published by A. C.

McClurg & Co. The book was never very widely read, and Miss Fisher

ceased to write for a while, plunging more deeply into her books and

study, reading in six languages the best that has been thought and said

in them, sloughing old opinions and growing into new ones, and then

the wish to say something awoke in her again and the result was "The

Journal of a Recluse," published anonymously by Crowell & Co., New

York. From the force of its style and directness of expression, as well

as maturity of thought, the authorship was ascribed to different persons

of literary fame, but no one thought the author was a woman. The

secret was kept for about tliree years, when her incognito was discovered

by some of her friends.

The book, which claims to be a translation from the French, was

really written at first entirely in French. Miss Fisher explains that fact

by saying that it was written in hours after school work was over, and

that her sensitiveness to any defect in the construction of her own language

sometimes impeded the flow of her own thought, but that in a foreign

tongue she felt no such restraint, and wrote more freely, caring not at

all in what way she expressed herself. She could furnish the expression

when she made the translation. It is possible that this accounts for

the remarkable clearness and rhythm of her prose. Her books, as an

acute critic says, have an individual distinction and charm of expression

wliich appeals to people who have a keen hterary instinct. The "Journal

of a Recluse" was a success in the best sense of the word; that is, it

found that audience whose approval means substantial merit in the work.

It was followed in last October by another novel, "Kirstie," and by "A

Valiant Woman — A Contribution to the Educational Problem," of which

Superintendent Greenwood, of Kansas City, wrote to the publisher, in

a desire to know the name of the author: "It is one of the best and

most sensible books on education that has come from the press of this

country in many years. The author knows real education from the

spurious article, and he puts his fingers on the weak spots, and he has

the courage of his convictions in the expression of his opinion. In these

days of soft pedagogy and sugary teaching, it is, indeed, refreshing to

read an author who has a great message and knows how to deliver it

to fair-minded people."

The author has probably more messages to deliver to us in the

future, and perhaps it is not an exaggeration to say that few women

since George Eliot have been better equipped in general learning for the

delivery of a message than Mary Fisher.

Of Scotch and English parentage, born on the prairies of Illinois,

about 130 miles south of Chicago, beginning her education in a village

school in wliich she was teaching at sixteen, self-educated, later through

wide reading and travel, learning her French, German, Spanish and

Italian in the countries in which they are the native tongues, and now

a teacher of modern languages in the McKinley High School of this city,

so runs the biography of Mary Fisher.

Frank and natural in manner, showing evidence of a wide intellec-

tual curiosity and a vivid sympathy with human nature, it is not difficult

to engage Miss Fisher in conversation, which reveals her trend of

thinking on the chief problems of modern life. Perhaps a quiet im-

perturbable common sense, better than anything else, will describe her

attitude to things in general. She does not believe in panaceas nor in

violent remedies; is inclined to think that true human progress is indefi-

nitely slow, subject to intermissions and relapses; that humanity gropes

its way instinctively towards the right rather than leaps into it by sudden

jumps or by legislative enactments.

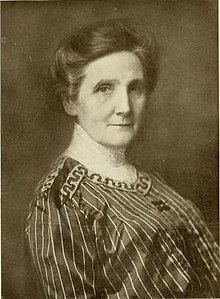

Mary Fisher is a little below the average height. Her eyes are gray

and they are penetrating and sympathetic, keen and kind, and her brown

hair is well sprinkled with gray. In manner, she is frank and unaffected,

ready to talk with anyone on any subject, and always more willing to

be interested in what interests someone else than to intrude her own

thoughts and tastes upon another.

She is a rare, fine woman — studious, thoughtful always — with an

irresistible charm over those with whom she comes in contact. She

knows the world and the people in it for what it is worth; her travels —

with her wonderful capacity of observation — enable her to gather informa-

tion from this experience and that, lop off absurdities, strengthen here

and bolster there, until in her mind there have grown up ideals which

she materializes in her writings.

Miss Fisher is a woman of genius.

Source: Johnson, Anne (1914). Notable women of St. Louis, 1914. St. Louis, Woodward. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

/A her hfe that would particularly interest the public, as it is chiefly

the story of her mental growth, we find that her life has been a par-

ticularly active one in many directions. She has been teacher, traveler,

writer, dramatic reader, lecturer, and has had the experience of a political

campaign, in consequence of the nomination for Superintendent of Schools

of Peoria County, Illinois.

Out of this latter experience she says that she early learned the inval-

uable lesson of the worthlessness of "they say," and that she resolved

never afterwards to be disturbed or grieved by calumny or criticism, so

long as she was conscientiously' doing her best.

Her earliest writings were short stories and sketches for a literary

paper of Peoria, but she discontinued this in a short time, feeling that a

longer preparation was necessary for serious literary work, and that before

doing anything more she ought to know what had already been written,

that she might judge whether she herself had anything worth while to say.

She read and studied incessantly, spai'ing no pains to acquaint herself with

the trend of modern thought. She studied French and German, feeling

that these two languages would give her access to scientific books which

she could not get in English. She varied her experiences in teaching by

changing her locality from time to time, and has taught in the high schools

of Lewiston, 111.; Springfield, Mo.; Ann Arbor, Mich.; Kansas City, Mo.,

and now in St. Louis. Twice she obtained a leave of absence, spending a

year in Scotland and England, and a year in Italy, where the Italian

language and literature were her chief subjects of study.

Her summers are usually spent abroad or in some interesting part of

America. She has traveled all over the British Isles and in France, Bel-

gium, Holland, Germanj', Switzerland, Italy and Spain. She has passed a

summer in New Brunswick and Novia Scotia, and another in the chief

cities of Old Mexico, still another in Honolulu, and several of them on the

Pacific Coast. It is to a summer in Quebec that we owe the setting of the

first part of her recent novel, "Kirstie."

This is one of the most interesting novels that has appeared for many

years. The principal character is a woman of heroic type. The analysis

reminds one forcibly of Jane Eyre. There is a delineation of passionate

love directed and controlled by an unfaltering virtue. The situations are

intensely dramatic. A continuous flow of reflections and comments of a

philosophic nature show the author's deep knowledge of humanity. The

descriptions of the places where the scenes are laid are faithfully and

beautifully portrayed — poetically, too, showing the capacity of a true

artist. This book is of the highest moral tone.

In 1896 Miss Fisher was attracted by the suggestive character of Max

Nordau's Entartung, which had just appeared, and made a translation of it

that was accepted by a prominent New York house on condition that Max

Nordau's consent could be obtained. Miss Fisher wrote to Max Nordau,

who replied that he had just disposed of the right of translation to a London

firm. The immense success of the book, which appeared simultaneously

in every modern European tongue, confirmed Miss Fisher's belief that how-

ever extravagant the book might be in some of its assertions, it had its

message for a generation that was mistaking ijathology for literature.

She says that the book made her feel that health — not disease, and moral-

ity — not debauchery, make the surest soil for sound literary productions.

About this time the "Valiant Woman" to whose memory Miss Fisher's

latest book is a loving tribute, engaged her in a correspondence on English

literature with a young girl of Santa Fe, N. M. Miss Fisher's letters were

read there to a woman's club, and learning of the favor they had received

she was led to submit them to a publisher as an aid to the young in answer-

ing that familiar question, "What shall I read?" They were published

by S. C. Griggs & Co., Chicago, III., whose successors, Scott, Foresman

& Co., still continue to publish thein under the title of "Twenty-five

Letters on English Authors." They are written in an easy, flowing style,

and abound in literary anecdotes and personal glimpses of the great men

and women whose works are the treasures of the English tongue. This

book was followed by "A General Survey of American Literature," pub-

lished by A. C. McCIurg & Co., Chicago.

After the publication of these two books Miss Fisher went to Boston

to avail herself of the advantages of the public library there. She wished

to study the literary criticism of France. For Saint Beuve she had a

profound admiration, and soon discovered that he was but the bright

particular star of a whole constellation of brilliant critics. Finding that

the names of these critics were almost, if not wholly, unknown to English

readers, she wished to share her enthusiasm with the public, and wrote

"A Group of French Critics," in which she gave a brief biographical sketch

of Edmond Scherer, Ernest Bersot, Saint-Marc Girardin, Ximenes Doudan

and Gustave Planche. In addition to the biography, she translated speci-

mens of the pungent criticism of these clever thinkers, hoping that the

sanity of their views might create a public demand for them in America.

The book attracted some good notices from the best reviewers, but the

general public was, and is, extremely indifferent to literary criticism,

and the book is now out of print, the plates having been recently destroyed.

Then Miss Fisher tried her hand at fiction. While in Glasgow,

Scotland, she had seen a good deal of the social work among the poor,

known as "slumming," and was not wholly converted to many of its

methods. She thought that the interest in the poor was rather a fad

among the idle rich than the result of the promptings of sincere sympathy,

and that it is not given to everj^one to act as an inspiration and a guide

to them. This is the theme of "Gertrude Dorrance," published by A. C.

McClurg & Co. The book was never very widely read, and Miss Fisher

ceased to write for a while, plunging more deeply into her books and

study, reading in six languages the best that has been thought and said

in them, sloughing old opinions and growing into new ones, and then

the wish to say something awoke in her again and the result was "The

Journal of a Recluse," published anonymously by Crowell & Co., New

York. From the force of its style and directness of expression, as well

as maturity of thought, the authorship was ascribed to different persons

of literary fame, but no one thought the author was a woman. The

secret was kept for about tliree years, when her incognito was discovered

by some of her friends.

The book, which claims to be a translation from the French, was

really written at first entirely in French. Miss Fisher explains that fact

by saying that it was written in hours after school work was over, and

that her sensitiveness to any defect in the construction of her own language

sometimes impeded the flow of her own thought, but that in a foreign

tongue she felt no such restraint, and wrote more freely, caring not at

all in what way she expressed herself. She could furnish the expression

when she made the translation. It is possible that this accounts for

the remarkable clearness and rhythm of her prose. Her books, as an

acute critic says, have an individual distinction and charm of expression

wliich appeals to people who have a keen hterary instinct. The "Journal

of a Recluse" was a success in the best sense of the word; that is, it

found that audience whose approval means substantial merit in the work.

It was followed in last October by another novel, "Kirstie," and by "A

Valiant Woman — A Contribution to the Educational Problem," of which

Superintendent Greenwood, of Kansas City, wrote to the publisher, in

a desire to know the name of the author: "It is one of the best and

most sensible books on education that has come from the press of this

country in many years. The author knows real education from the

spurious article, and he puts his fingers on the weak spots, and he has

the courage of his convictions in the expression of his opinion. In these

days of soft pedagogy and sugary teaching, it is, indeed, refreshing to

read an author who has a great message and knows how to deliver it

to fair-minded people."

The author has probably more messages to deliver to us in the

future, and perhaps it is not an exaggeration to say that few women

since George Eliot have been better equipped in general learning for the

delivery of a message than Mary Fisher.

Of Scotch and English parentage, born on the prairies of Illinois,

about 130 miles south of Chicago, beginning her education in a village

school in wliich she was teaching at sixteen, self-educated, later through

wide reading and travel, learning her French, German, Spanish and

Italian in the countries in which they are the native tongues, and now

a teacher of modern languages in the McKinley High School of this city,

so runs the biography of Mary Fisher.

Frank and natural in manner, showing evidence of a wide intellec-

tual curiosity and a vivid sympathy with human nature, it is not difficult

to engage Miss Fisher in conversation, which reveals her trend of

thinking on the chief problems of modern life. Perhaps a quiet im-

perturbable common sense, better than anything else, will describe her

attitude to things in general. She does not believe in panaceas nor in

violent remedies; is inclined to think that true human progress is indefi-

nitely slow, subject to intermissions and relapses; that humanity gropes

its way instinctively towards the right rather than leaps into it by sudden

jumps or by legislative enactments.

Mary Fisher is a little below the average height. Her eyes are gray

and they are penetrating and sympathetic, keen and kind, and her brown

hair is well sprinkled with gray. In manner, she is frank and unaffected,

ready to talk with anyone on any subject, and always more willing to

be interested in what interests someone else than to intrude her own

thoughts and tastes upon another.

She is a rare, fine woman — studious, thoughtful always — with an

irresistible charm over those with whom she comes in contact. She

knows the world and the people in it for what it is worth; her travels —

with her wonderful capacity of observation — enable her to gather informa-

tion from this experience and that, lop off absurdities, strengthen here

and bolster there, until in her mind there have grown up ideals which

she materializes in her writings.

Miss Fisher is a woman of genius.

Source: Johnson, Anne (1914). Notable women of St. Louis, 1914. St. Louis, Woodward. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement