b.Berlin

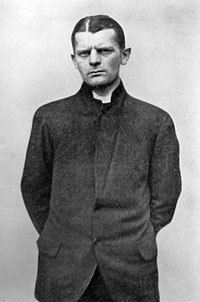

Carl Hans Lody ( name sometimes given as Gustav Carl/ Karl Gottlieb Hans Lody) was executed as a German spy by Great Britain at the Tower of London soon after the outbreak of World War I.

Lody hailed from a family of soldiers and civil servants. As a child, Lody wished to become a seafarer, so he moved to Hamburg and became a cabin boy. In 1904, he graduated from a maritime academy in Geestemünde, passing the exams to become a captain with flying colors.

He had been a personal acquaintance of the first director of German Naval Intelligence, Commander Fritz Prieger, and in May 1914 he volunteered for service with the department. Becoming seriously ill soon thereafter, he was unable to actually become a captain, so he became a tourist guide for Hapag instead.

After a state of imminent threat of war was declared in Germany on July 31, 1914, Lody volunteered as an Oberleutnant zur See, offering to go to the United Kingdom in order to report on the movements of the British fleet. At first he was turned down. He then obtained an American passport from the US consulate under the name Charles A. Inglis by claiming he had lost his old one. He was facilitated by the fact that he spoke English perfectly with an American accent, having been married to an American woman and lived in Omaha, Nebraska. This passport permitted Lody to travel all over Europe without any restrictions and made him of great value to the German military and they then accepted him.

Lody received no more than a very basic preparation but the Germans provided him with a substantial amount of money. According to the German Admiralty's files, "if or when Mr. Lody comes to know that a naval battle has taken place, he will enquire as much and as unobtrusively as possible regarding losses, damage etc."

Originally assigned to Southern France, he was then sent to Edinburgh, which was of great importance to the Royal Navy. The Firth of Forth, the large estuary to the north of Edinburgh, was of great strategic importance. As well as being the main seaward approach to the Scottish capital and the site of the Forth Bridge, it was used as an anchorage by dozens of Royal Navy ships. The area was heavily fortified with gun batteries and minefields to protect it against attacks from the sea. He travelled from Hamburg via neutral Norway and then Newcastle and arriving in Scotland on August 25. He stayed at the North British Hotel and took the bus to the Firth of Forth every morning. Just five days into his mission he sent his first report back to Germany, a telegram transmitted via Sweden. It read:

"must cancel. Johnson very ill. Lost four days. Shall eav [sic] shortly. Charles",

-indicating that there were four ships being repaired at the dock and that there were several units about to head out to sea. The German submarine U-21 immediately received orders to attack in this area. The lead ship of the Pathfinder class scout cruisers, HMS Pathfinder, then became the first ship ever sunk by a torpedo fired from a submarine.

After this, Lody no longer felt safe staying at the hotel, especially as he had named his address in the telegram. He rented a bicycle in order to be able to move around more effectively. Lody travelled to Dublin in Ireland on 29 September, travelling via the busy port of Liverpool. He took the opportunity to write a detailed letter in German describing ships in the harbour and conversations that he had overheard. The fact that they were written in German led the authorities to check their content.

Unlike some of his earlier letters, it contained information of real military value to the Germans, but was written without any coding. Postal censors intercepted the letter and MI5 decided to order his arrest.

He did not know that MI5 was monitoring letters and telegrams abroad, or that his messages would be intercepted.

Lody was detected in his very first message home, which had been sent to an Adolf Buchard in Stockholm. MI5 knew that this address was a cover for German intelligence. Any messages sent there were intercepted and Lody's correspondence made it clear that a German spy was active in Britain. His identity was not known at that stage, as he signed his messages "Charles" or "Nazi". (The latter alias had no connection with Adolf Hitler's party, which was founded after WWI. Before then, the word "Nazi" was used as a short form of the name "Ignatz"; it was also a nickname for Austro-Hungarian soldiers. During his month in Edinburgh, Lody sent regular messages in English and German to his contacts in Stockholm. Some of these were allowed to go through because they contained misleading information that would alarm the Germans but cause no harm to the British cause. For instance, he sent letters about a supposed landing of "large numbers of Russian troops" in Scotland, repeating an infamous rumour that thousands of Russians "with snow on their boots" had been sent to fight on the Western Front. There was no truth in the story but it caused great concern to the German military.

On October 20, Lody moved to Killarney, Ireland staying at the Great Southern Hotel. While he was dining there, several police officers approached him. Although, Lody insisted that he was an American, he was arrested as a suspected German agent. The search of his room turned up more evidence against him: German coins, a notebook with the content of the first telegram, German addresses, drafts of his letters, and a bus ticket from Edinburgh to the Firth of Forth. The next day Lody's coat was found in Edinburgh, containing the name of a tailor's shop in Berlin and Lody's real name.

Having been arrested and transported back to London, Lody was put on trial for "war treason", a rarely-used charge which treated espionage as a war crime and was punishable by the death penalty.

At his trial, he claimed that he had not wanted to become a spy and had sought an exemption from service on medical grounds so that he could return to New York. However, the German admiralty's files show that Lody had in fact become a spy of his own free will and had signed a formal agreement with the naval intelligence department before the war had begun.

Unlike most spies, he received a public trial with his case being reported widely in the press. He refused to name Fritz Prieger, the person who had recruited him: "that name I cannot say as I have given my word of honour".

His declarations of patriotism and honour attracted widespread admiration in both Britain and Germany. Lody's story is retold in detail in Shot in the Tower, by Leonard Sellers. Files on the case from the War Office and Director of Public Prosecutions can be viewed at The National Archives.

Detained at Wellington Barracks near Buckingham Palace, he was convicted of war treason on November 2 and sentenced to death. Four days later when he was taken to the Tower of London to be executed he was reported to have said to the officer who escorted him from his cell to the execution shed "I suppose that you will not care to shake hands with a German spy". "No," the officer replied; "but I will shake hands with a brave man."

According to A.W. Brian Simpson in Domestic and International Trials 1700-2000, the case was a legal landmark as the first espionage trial in England held partly in camera —but the case was widely reported in the press.

The outcome, however, was a foregone conclusion, and Lody himself didn't bother to contest his guilt — seemingly fixated on going to his grave with nothing short of the utmost in romantic gentlemanly decorum.

Lody was executed in a miniature rifle range (a wooden shed erected for the purpose in the Tower yard. ) in the Tower of London. Ten more German spies, who seem to have had a harder go of infiltrating Britain than their English counterparts had in Germany, would suffer the same fate by war's end.

The execution was carried out by an eight-man firing squad. He was buried within the precincts of the Tower. Lody was the first person since the Jacobite rebel Lord Lovat, who was beheaded there in 1747, to be executed in the Tower of London. He was also the first German spy in World War I to be executed in the United Kingdom.

Excerpts from the last letters Lody wrote were published soon after his death. One was written to a friend of his in Omaha, the other, the last letter he ever wrote, to his sister; it was published in the Frankfurter Zeitung.

A German destroyer, the Hans Lody, was named after him.

Years later, German officials wished to visit his grave and it became apparent that he had been buried in an unmarked mass grave. A secret debate then ensued. It was decided that the British should first determine how spies were treated by the Germans, before they allowed the Germans to know about Lody.

Bio Supplied by geoffrey gillon

Information from German War Graves

Aftername: Lody

Vo: name: Karl

Rank: Lieutenant of the reserve

Date of Birth: 20/01/1877

Birthplace:

Todes-/Vermisstendatum: 06/11/1914

Todes-/Vermisstenort: Tower of London

b.Berlin

Carl Hans Lody ( name sometimes given as Gustav Carl/ Karl Gottlieb Hans Lody) was executed as a German spy by Great Britain at the Tower of London soon after the outbreak of World War I.

Lody hailed from a family of soldiers and civil servants. As a child, Lody wished to become a seafarer, so he moved to Hamburg and became a cabin boy. In 1904, he graduated from a maritime academy in Geestemünde, passing the exams to become a captain with flying colors.

He had been a personal acquaintance of the first director of German Naval Intelligence, Commander Fritz Prieger, and in May 1914 he volunteered for service with the department. Becoming seriously ill soon thereafter, he was unable to actually become a captain, so he became a tourist guide for Hapag instead.

After a state of imminent threat of war was declared in Germany on July 31, 1914, Lody volunteered as an Oberleutnant zur See, offering to go to the United Kingdom in order to report on the movements of the British fleet. At first he was turned down. He then obtained an American passport from the US consulate under the name Charles A. Inglis by claiming he had lost his old one. He was facilitated by the fact that he spoke English perfectly with an American accent, having been married to an American woman and lived in Omaha, Nebraska. This passport permitted Lody to travel all over Europe without any restrictions and made him of great value to the German military and they then accepted him.

Lody received no more than a very basic preparation but the Germans provided him with a substantial amount of money. According to the German Admiralty's files, "if or when Mr. Lody comes to know that a naval battle has taken place, he will enquire as much and as unobtrusively as possible regarding losses, damage etc."

Originally assigned to Southern France, he was then sent to Edinburgh, which was of great importance to the Royal Navy. The Firth of Forth, the large estuary to the north of Edinburgh, was of great strategic importance. As well as being the main seaward approach to the Scottish capital and the site of the Forth Bridge, it was used as an anchorage by dozens of Royal Navy ships. The area was heavily fortified with gun batteries and minefields to protect it against attacks from the sea. He travelled from Hamburg via neutral Norway and then Newcastle and arriving in Scotland on August 25. He stayed at the North British Hotel and took the bus to the Firth of Forth every morning. Just five days into his mission he sent his first report back to Germany, a telegram transmitted via Sweden. It read:

"must cancel. Johnson very ill. Lost four days. Shall eav [sic] shortly. Charles",

-indicating that there were four ships being repaired at the dock and that there were several units about to head out to sea. The German submarine U-21 immediately received orders to attack in this area. The lead ship of the Pathfinder class scout cruisers, HMS Pathfinder, then became the first ship ever sunk by a torpedo fired from a submarine.

After this, Lody no longer felt safe staying at the hotel, especially as he had named his address in the telegram. He rented a bicycle in order to be able to move around more effectively. Lody travelled to Dublin in Ireland on 29 September, travelling via the busy port of Liverpool. He took the opportunity to write a detailed letter in German describing ships in the harbour and conversations that he had overheard. The fact that they were written in German led the authorities to check their content.

Unlike some of his earlier letters, it contained information of real military value to the Germans, but was written without any coding. Postal censors intercepted the letter and MI5 decided to order his arrest.

He did not know that MI5 was monitoring letters and telegrams abroad, or that his messages would be intercepted.

Lody was detected in his very first message home, which had been sent to an Adolf Buchard in Stockholm. MI5 knew that this address was a cover for German intelligence. Any messages sent there were intercepted and Lody's correspondence made it clear that a German spy was active in Britain. His identity was not known at that stage, as he signed his messages "Charles" or "Nazi". (The latter alias had no connection with Adolf Hitler's party, which was founded after WWI. Before then, the word "Nazi" was used as a short form of the name "Ignatz"; it was also a nickname for Austro-Hungarian soldiers. During his month in Edinburgh, Lody sent regular messages in English and German to his contacts in Stockholm. Some of these were allowed to go through because they contained misleading information that would alarm the Germans but cause no harm to the British cause. For instance, he sent letters about a supposed landing of "large numbers of Russian troops" in Scotland, repeating an infamous rumour that thousands of Russians "with snow on their boots" had been sent to fight on the Western Front. There was no truth in the story but it caused great concern to the German military.

On October 20, Lody moved to Killarney, Ireland staying at the Great Southern Hotel. While he was dining there, several police officers approached him. Although, Lody insisted that he was an American, he was arrested as a suspected German agent. The search of his room turned up more evidence against him: German coins, a notebook with the content of the first telegram, German addresses, drafts of his letters, and a bus ticket from Edinburgh to the Firth of Forth. The next day Lody's coat was found in Edinburgh, containing the name of a tailor's shop in Berlin and Lody's real name.

Having been arrested and transported back to London, Lody was put on trial for "war treason", a rarely-used charge which treated espionage as a war crime and was punishable by the death penalty.

At his trial, he claimed that he had not wanted to become a spy and had sought an exemption from service on medical grounds so that he could return to New York. However, the German admiralty's files show that Lody had in fact become a spy of his own free will and had signed a formal agreement with the naval intelligence department before the war had begun.

Unlike most spies, he received a public trial with his case being reported widely in the press. He refused to name Fritz Prieger, the person who had recruited him: "that name I cannot say as I have given my word of honour".

His declarations of patriotism and honour attracted widespread admiration in both Britain and Germany. Lody's story is retold in detail in Shot in the Tower, by Leonard Sellers. Files on the case from the War Office and Director of Public Prosecutions can be viewed at The National Archives.

Detained at Wellington Barracks near Buckingham Palace, he was convicted of war treason on November 2 and sentenced to death. Four days later when he was taken to the Tower of London to be executed he was reported to have said to the officer who escorted him from his cell to the execution shed "I suppose that you will not care to shake hands with a German spy". "No," the officer replied; "but I will shake hands with a brave man."

According to A.W. Brian Simpson in Domestic and International Trials 1700-2000, the case was a legal landmark as the first espionage trial in England held partly in camera —but the case was widely reported in the press.

The outcome, however, was a foregone conclusion, and Lody himself didn't bother to contest his guilt — seemingly fixated on going to his grave with nothing short of the utmost in romantic gentlemanly decorum.

Lody was executed in a miniature rifle range (a wooden shed erected for the purpose in the Tower yard. ) in the Tower of London. Ten more German spies, who seem to have had a harder go of infiltrating Britain than their English counterparts had in Germany, would suffer the same fate by war's end.

The execution was carried out by an eight-man firing squad. He was buried within the precincts of the Tower. Lody was the first person since the Jacobite rebel Lord Lovat, who was beheaded there in 1747, to be executed in the Tower of London. He was also the first German spy in World War I to be executed in the United Kingdom.

Excerpts from the last letters Lody wrote were published soon after his death. One was written to a friend of his in Omaha, the other, the last letter he ever wrote, to his sister; it was published in the Frankfurter Zeitung.

A German destroyer, the Hans Lody, was named after him.

Years later, German officials wished to visit his grave and it became apparent that he had been buried in an unmarked mass grave. A secret debate then ensued. It was decided that the British should first determine how spies were treated by the Germans, before they allowed the Germans to know about Lody.

Bio Supplied by geoffrey gillon

Information from German War Graves

Aftername: Lody

Vo: name: Karl

Rank: Lieutenant of the reserve

Date of Birth: 20/01/1877

Birthplace:

Todes-/Vermisstendatum: 06/11/1914

Todes-/Vermisstenort: Tower of London

Gravesite Details

Black headstone (Polished )with gold letters erected 26.11.74

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

Advertisement