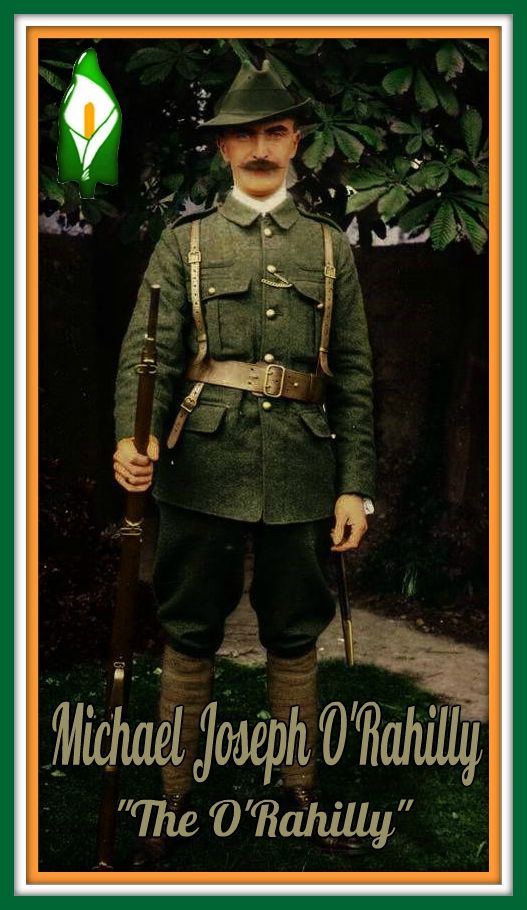

Michael Joseph O'Rahilly was born on April 22, 1875 to a prosperous merchant family in Ballylongford, Co. Kerry . After receiving his primary education at the local national school he attended the Jesuit-run Clongowes Wood College a private secondary education boarding school for wealthy Catholics. He was taught Irish during his early years by his primary school principal who was a native speaker from An Daingean in Kerry.

In the fall of 1893 he entered the Royal University of Ireland in Dublin as a medical student. Within a year of entering the university he contacted tuberculosis causing him to abandon his studies for the duration of his illness. When his father died in 1896 his left the university for good to attend to the family business in Ballylongford. He sold the business in 1898 and shortly afterwards set sail for the United States.

In 1899 he married Nancy Browne a native of Philadelphia whom he had met during the summer of 1893. The daughter of a wealthy Philadelphia businessman she attended school in Paris and was vacationing in Ireland when they first met. For their honeymoon they toured Europe visiting among other countries France, Austria and Italy. Nancy was a fluent in French having learned it during her schooling in France. Not to be outdone, O'Rahilly studied French and went on to master the language as he had mastered Irish in his youth. After their honeymoon they settled in New York.

After returning to Dublin in 1902 with his family he was appointed Justice of the Peace a position he held before leaving for the USA in 1898.

For the next three years he spent some time travelling Ireland researching his ancestry. He wrote for Arthur Griffith's nationalist newspaper the 'United Irishman'. He also spent time in England and was involved with John Redmond's Home Rule Party. In 1905 he returned to the USA to help rescue the Browne family business. For the next four years the O'Rahilly family lived in a mansion named 'Sliabh Luachra' in the fashionable Drexel Hill suburb of Philadelphia.

In 1909 the family returned to Dublin. By this time O'Rahilly had became more deeply involved in politics and had developed strong nationalist views. He contributor to Arthur Griffith's newspaper 'Sinn Fein' successor to the 'United Irishman' that went out of circulation in 1906. As a member of Sinn Fein he worked tirelessly to promote Irish industries.

During the visit of King George V to Dublin in July, 1911, O'Rahilly placed a banner across Grafton St. reading: "Thou art not conquered yet. dear land". The banner generated a lot of publicity before it was torn down.

Thomas Clarke, another martyr of the 1916 Easter Rising, who also had lived in the USA for some time, organized the first pilgrimage to Wolfe Tone's grave at Bodenstown in Co. Kildare, as a counter to the same royal visit.

In 1912, O'Rahilly was elected to the Coiste Gnó (Executive) of Conradh na Gaeilge (the Gaelic League). He became editor of its journal An Claidheamh Soluis (The Sword of Light). In 1913 he persuaded Eoin MacNéill , a founding member of the Gaelic League, to write an article for a new series of articles planned for the Claidheamh Soluis. Eoin MacNéill obliged and submitted his article ‘The North Began'. On November 25, 1913 following the publication of ‘The North Began' an article that advocated the formation of a National Volunteer Force. In response to that article the Irish Volunteers were founded with MacNeill as Commander in Chief.

The primary objective of the Irish Volunteers was to counter the threat posed by the Ulster Volunteers formed in 1912. Its declared aim was to "to secure and maintain the rights and liberties common to the whole people of Ireland"

For the next two years O'Rahilly served as Treasurer of the Volunteers. On September of 1914, John Redmond, the leader of the Home Rule Party called on the volunteers to enlist in the British Army. As a result of Redmond's treachery, O'Rahilly parted ways and took over as Director of Arms of the secessionists Volunteers. He was chairman of the group that organized the purchase of arms for the Volunteers.

The arms, which consisted of German rifles and ammunition were smuggled into Howth in Co. Dublin and Kilcoole in Co. Wicklow aboard the yacht's Asgard and the Kelpie. The Asgard was captained by Erskine Childers assisted by his wife Molly. Childers was executed in 1922 by the British supported Free State regime during the second phase of the War of Independence commonly referred to as the Irish Civil War. The yacht Kelpie was captained by Edward Conor Marshall O'Brien

John Redmond's scheming in trying to take over and suppress the Volunteers were exposed in O'Rahilly's pamphlet The Secret History of the Irish Volunteers.

Despite being a founding member of the Volunteers, O'Rahilly had no knowledge or role in the planning of the Easter Rising. In the days leading up to the Rising he worked with Mac Néill to stop it. Despite his best efforts to prevent what he later described as "madness but glorious madness" he did not hesitate to join once he realized the Rising could not be stopped. Having made up his mind he made his way to Liberty Hall to join Pearse, Connolly , Clarke, and the other leaders. Upon arriving at Liberty Hall in his De Dion-Bouton motorcar he uttered one of the most quoted lines of the rising, "Well, I've helped to wind up the clock -- I might as well hear it strike!".

O'Rahilly fought with the GPO garrison during Easter Week. On Friday April 28, with the GPO on fire he volunteered to lead a party of 12 men in search of a route out of the GPO to Williams and Woods, a factory on Great Britain Street (now Parnell Street). A British machine-gun at the intersection of Great Britain Street and Moore Street caught him along with most of his party. He slumped into a doorway on Moore Street, wounded and bleeding badly but soon made a dash across the road to find shelter in Sackville Lane (now O'Rahilly Parade). With this attempt to find shelter, O'Rahilly again exposed himself to sustained fire from the machine-guns

It is often mooted that nineteen hours after receiving his wounds on Friday evening and long after the surrender had taken place on Saturday afternoon, O'Rahilly still clung to life. This story comes from a Red Cross ambulance driver, Albert Mitchell. The following is an extract from Mitchell's witness statement, now lodged in the Military Bureau collection (WS 196) and recently made available to the public:

The sergeant drew my attention to the body of a man lying in the gutter in Moore Lane. He was dressed in a green uniform. I took the sergeant and two men with a stretcher and approached the body which appeared to be still alive. We were about to lift it up when a young English officer stepped out of a doorway and refused to allow us to touch it. I told him of my instructions from H.Q. but all to no avail.

When back in the lorry I asked the sergeant what was the idea? His answer was – ‘he must be someone of importance and the bastards are leaving him there to die of his wounds. It's the easiest way to get rid of him.'

We came back again about 9 o'clock that night. The body was still there and an officer guarding it, but this time I fancied I knew the officer – he was not the one I met before. I asked why I was not allowed to take the body and who was it? He replied that his life and job depended on it being left there. He would not say who it was. I never saw the body again but I was told by different people that it was The O'Rahilly.

The specific timing of The O'Rahilly's death is very difficult to pin down faithfully but we can be more precise when it comes to gaining an understanding of his final thoughts. Despite his obvious pain he took the time to write a message to his wife on the back of a letter he had received in the GPO from his son. It is this last message to Nancy that artist Shane Cullen has etched into his limestone and bronze sculpture. The text reads:

Written after I was shot. Darling Nancy I was shot leading a rush up Moore Street and took refuge in a doorway. While I was there I heard the men pointing out where I was and made a bolt for the laneway I am in now.

I got more [than] one bullet I think. Tons and tons of love dearie to you and the boys and to Nell and Anna. It was a good fight anyhow. Please deliver this to Nannie O' Rahilly, 40 Herbert Park, Dublin. Goodbye Darling.

He died on Easter Saturday and was buried in Glasnevin Cemetery as the prison executions of his comrades were beginning.

His name in his native Irish Gaelic language:

Mícheál Seosamh Ó Rathaille or Ua Rathghaille

Michael Joseph O'Rahilly was born on April 22, 1875 to a prosperous merchant family in Ballylongford, Co. Kerry . After receiving his primary education at the local national school he attended the Jesuit-run Clongowes Wood College a private secondary education boarding school for wealthy Catholics. He was taught Irish during his early years by his primary school principal who was a native speaker from An Daingean in Kerry.

In the fall of 1893 he entered the Royal University of Ireland in Dublin as a medical student. Within a year of entering the university he contacted tuberculosis causing him to abandon his studies for the duration of his illness. When his father died in 1896 his left the university for good to attend to the family business in Ballylongford. He sold the business in 1898 and shortly afterwards set sail for the United States.

In 1899 he married Nancy Browne a native of Philadelphia whom he had met during the summer of 1893. The daughter of a wealthy Philadelphia businessman she attended school in Paris and was vacationing in Ireland when they first met. For their honeymoon they toured Europe visiting among other countries France, Austria and Italy. Nancy was a fluent in French having learned it during her schooling in France. Not to be outdone, O'Rahilly studied French and went on to master the language as he had mastered Irish in his youth. After their honeymoon they settled in New York.

After returning to Dublin in 1902 with his family he was appointed Justice of the Peace a position he held before leaving for the USA in 1898.

For the next three years he spent some time travelling Ireland researching his ancestry. He wrote for Arthur Griffith's nationalist newspaper the 'United Irishman'. He also spent time in England and was involved with John Redmond's Home Rule Party. In 1905 he returned to the USA to help rescue the Browne family business. For the next four years the O'Rahilly family lived in a mansion named 'Sliabh Luachra' in the fashionable Drexel Hill suburb of Philadelphia.

In 1909 the family returned to Dublin. By this time O'Rahilly had became more deeply involved in politics and had developed strong nationalist views. He contributor to Arthur Griffith's newspaper 'Sinn Fein' successor to the 'United Irishman' that went out of circulation in 1906. As a member of Sinn Fein he worked tirelessly to promote Irish industries.

During the visit of King George V to Dublin in July, 1911, O'Rahilly placed a banner across Grafton St. reading: "Thou art not conquered yet. dear land". The banner generated a lot of publicity before it was torn down.

Thomas Clarke, another martyr of the 1916 Easter Rising, who also had lived in the USA for some time, organized the first pilgrimage to Wolfe Tone's grave at Bodenstown in Co. Kildare, as a counter to the same royal visit.

In 1912, O'Rahilly was elected to the Coiste Gnó (Executive) of Conradh na Gaeilge (the Gaelic League). He became editor of its journal An Claidheamh Soluis (The Sword of Light). In 1913 he persuaded Eoin MacNéill , a founding member of the Gaelic League, to write an article for a new series of articles planned for the Claidheamh Soluis. Eoin MacNéill obliged and submitted his article ‘The North Began'. On November 25, 1913 following the publication of ‘The North Began' an article that advocated the formation of a National Volunteer Force. In response to that article the Irish Volunteers were founded with MacNeill as Commander in Chief.

The primary objective of the Irish Volunteers was to counter the threat posed by the Ulster Volunteers formed in 1912. Its declared aim was to "to secure and maintain the rights and liberties common to the whole people of Ireland"

For the next two years O'Rahilly served as Treasurer of the Volunteers. On September of 1914, John Redmond, the leader of the Home Rule Party called on the volunteers to enlist in the British Army. As a result of Redmond's treachery, O'Rahilly parted ways and took over as Director of Arms of the secessionists Volunteers. He was chairman of the group that organized the purchase of arms for the Volunteers.

The arms, which consisted of German rifles and ammunition were smuggled into Howth in Co. Dublin and Kilcoole in Co. Wicklow aboard the yacht's Asgard and the Kelpie. The Asgard was captained by Erskine Childers assisted by his wife Molly. Childers was executed in 1922 by the British supported Free State regime during the second phase of the War of Independence commonly referred to as the Irish Civil War. The yacht Kelpie was captained by Edward Conor Marshall O'Brien

John Redmond's scheming in trying to take over and suppress the Volunteers were exposed in O'Rahilly's pamphlet The Secret History of the Irish Volunteers.

Despite being a founding member of the Volunteers, O'Rahilly had no knowledge or role in the planning of the Easter Rising. In the days leading up to the Rising he worked with Mac Néill to stop it. Despite his best efforts to prevent what he later described as "madness but glorious madness" he did not hesitate to join once he realized the Rising could not be stopped. Having made up his mind he made his way to Liberty Hall to join Pearse, Connolly , Clarke, and the other leaders. Upon arriving at Liberty Hall in his De Dion-Bouton motorcar he uttered one of the most quoted lines of the rising, "Well, I've helped to wind up the clock -- I might as well hear it strike!".

O'Rahilly fought with the GPO garrison during Easter Week. On Friday April 28, with the GPO on fire he volunteered to lead a party of 12 men in search of a route out of the GPO to Williams and Woods, a factory on Great Britain Street (now Parnell Street). A British machine-gun at the intersection of Great Britain Street and Moore Street caught him along with most of his party. He slumped into a doorway on Moore Street, wounded and bleeding badly but soon made a dash across the road to find shelter in Sackville Lane (now O'Rahilly Parade). With this attempt to find shelter, O'Rahilly again exposed himself to sustained fire from the machine-guns

It is often mooted that nineteen hours after receiving his wounds on Friday evening and long after the surrender had taken place on Saturday afternoon, O'Rahilly still clung to life. This story comes from a Red Cross ambulance driver, Albert Mitchell. The following is an extract from Mitchell's witness statement, now lodged in the Military Bureau collection (WS 196) and recently made available to the public:

The sergeant drew my attention to the body of a man lying in the gutter in Moore Lane. He was dressed in a green uniform. I took the sergeant and two men with a stretcher and approached the body which appeared to be still alive. We were about to lift it up when a young English officer stepped out of a doorway and refused to allow us to touch it. I told him of my instructions from H.Q. but all to no avail.

When back in the lorry I asked the sergeant what was the idea? His answer was – ‘he must be someone of importance and the bastards are leaving him there to die of his wounds. It's the easiest way to get rid of him.'

We came back again about 9 o'clock that night. The body was still there and an officer guarding it, but this time I fancied I knew the officer – he was not the one I met before. I asked why I was not allowed to take the body and who was it? He replied that his life and job depended on it being left there. He would not say who it was. I never saw the body again but I was told by different people that it was The O'Rahilly.

The specific timing of The O'Rahilly's death is very difficult to pin down faithfully but we can be more precise when it comes to gaining an understanding of his final thoughts. Despite his obvious pain he took the time to write a message to his wife on the back of a letter he had received in the GPO from his son. It is this last message to Nancy that artist Shane Cullen has etched into his limestone and bronze sculpture. The text reads:

Written after I was shot. Darling Nancy I was shot leading a rush up Moore Street and took refuge in a doorway. While I was there I heard the men pointing out where I was and made a bolt for the laneway I am in now.

I got more [than] one bullet I think. Tons and tons of love dearie to you and the boys and to Nell and Anna. It was a good fight anyhow. Please deliver this to Nannie O' Rahilly, 40 Herbert Park, Dublin. Goodbye Darling.

He died on Easter Saturday and was buried in Glasnevin Cemetery as the prison executions of his comrades were beginning.

His name in his native Irish Gaelic language:

Mícheál Seosamh Ó Rathaille or Ua Rathghaille

Inscription

UA RATHGHAILLE

Ceannphort Óglach na-hÉireann

d'éag san eirghe amach 1916

agus a bhean

NEANS

d'éag an t-aonmhadh lá déag d'Aibreán 1961

Beannacht Dé lena N-Anmanna