Son of Rev. Jeffrey Gilliam Murrell (1738 Lunenburg, VA - 11/25/1824 Williamson County, TN) and Zelphia Andrews Murrell.

On March 5, 1829 in Maury County, TN, married Elizabeth Mangham (1810 South Harpeth, Williamson County, TN - March 5, 1891 Chester County, Tennessee)

THE PULASKI CITIZEN

March 26, 1885

The Widow of Jno. A. Murrell.

"The widow of the bandit, John Andrews Murrell, is a resident of the Henderson section of Chester County. She is a kind, amiable old lady and is highly respected in the neighborhood." - Lexington Progress

From a personal acquaintance with the lady above mentioned, we are prepared to indorse as a truth the statement of the Progress. She is, indeed, a woman possessing in an eminent degree the qualities attributed. The writer has had many conversations with her, but in no instance did she ever refer to her husband or his notorious deeds. On that subject she has ever remained silent, and every effort to get her to speak of him or his deeds fail. It is believed that she possesses important papers concerning the life of her husband, and may, sometime in the near future, place them in the hands of some trusted person as data for a truthful history of the man whose deeds are memorable in the history and tradition of this section.

Mrs. Jno. A. Murrell is a rapid talker, and has a very retentive memory from which she produces many interesting incidents of more than half a century ago which are interwoven in our local and state history. Her descendants are living principally in Chester and Hardeman counties and are all good citizens. She has no permanent home, but lives among her children and other relatives. After Murrell's death she married a second time to Mr. Bland, who died several years ago. Time has whitened her locks and furrowed her cheek, but upon the aged countenance clusters the light of a benignant soul. Despite age, her eyes retain their sight, and when in animated conversation they sparkle with as much brilliancy as those of youth. We do not know her exact age, but she is at least an octogenarian. Full of life, energy, yielding not to the pressure of years, this kind old lady moves toward the evening horizon of life, affable, generous and unostentatious. - Tribune and Sun.

CHILDREN:

1. Leanna E. Jane Murrell (abt. 1829 TN-____). She married William T. Davis on April 15, 1853 in Madison County, TN.

2. Jeffrey Murrell (1830, Denmark, Madison County, TN-____)

3. John Andrews Murrell, Jr. (1834 Wayne County, TN - February 15, 1865 Pikesville, Bledsoe County, Tennessee)

4. Arthusy Madeline Murrell (1833 Pikeville, TN - 1891 Henderson, McNairy County, TN) married Robert B. Bland (1825 Wilson County, TN - 1869 McNairy County, TN) and they had the following children: Sarah L Bland (1849–____) she married William Gilding; John I. Bland (3/21/1851 TN– 12/24/1925 TN) [He married first Edna L Corley(1849–1915) and had children Lula Belle Bland (1889–1990) and he married second Anna Bell Elder (1864–____) and had William Cleveland Bland (1887–1967) and married third Mary J Bland (1856–1882)]; Mary Elizabeth Bland (1853 McNairy Co, TN–____); Rachel Ann Penelope Bland (Abt 1859–1895 McNairy Co, TN); Robert Allen Bland (1861–11/22/1939 Jackson, Madison Co, TN); Henry J Bland (1863–____); Lavanda D Bland (1866–1929) [She married Andrew Jack Campbell Jr (1854–1918) and had children Robert Campbell (1892–___), Florence Leona Campbell (1896–1991), John Campbell (1898–____), Edith Ellen Campbell (1904–1989), Purrie Beatrice Campbell (1906–1982), Bertha Campbell (1908–____)]; Nancy C. Bland (1868–____); Virginia Ophelia Bland (1874-1955) and Julie or Juley Bland (Abt 1878 TN–____).

5. Missouri F. Murrell (6/24/1833 Pikeville,TN - 4/21/1873 McNairy County, TN- burial Haltoms Chapel Cemetery, Chester Co, Tennessee). She married Benjamin Thomas Hardy (5/18/1828 Pittsylvania Co., VA-___) on April 21, 1853 in Madison County, Tn and they had the following children: James T. Hardy (b. ABT 1854 Tennessee); Joseph H. Hardy (b. ABT 1856 in Tennessee); John G. T. Hardy (b. ABT 1859 in Tennessee); Nancy F. Hardy (b. 24 OCT 1860 in McNairy Co, Tennessee; Burial- Haltoms Chapel Cemetery, Chester Co, Tennessee ) and William S. Hardy (b. ABT 1863 in McNairy Co, Tennessee)

John's father, Jeffery Murrell, brother of Thomas Murrell (1737 Goochland, Virginia-26 MAY 1826 Dickson, Dickson, Tennessee), moved to Middle Tennessee and he purchased 146 acres in Williamson County, a short distance from Dickson County. His land adjoined that of another brother, Drury, and was near his father-in-law, Mark Andrews, son of William A. Andrews, Sr.

John Andrews Murrell's Uncle Thomas' children all made respectable citizens, but Jeffery was not quite as fortunate. It is Jeffery's children that are "Our Outlaw Cousins."

Jeffery was an itinerant preacher and traveled throughout the countryside preaching the Gospel of Christ. His reputation was spotless, but his high morals were not shared by John Andrews. Murrell.

There is a book (something like 'Rouges and Vagabonds') which has an account of John Andrews Murrell.

According to family members, John Andrews Murrell has been much maligned by the sensational phamplet of Virgil Stewart in 1835 (The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture) and still later by the fabricated tale of Robert M. Coates. John's father, Jeffrey, was a Methodist minister, and his son John Andrews Murrell was found guilty of being a horse thief and later of harboring a slave. They assert that virtually all other stories about him are unsupported by facts or evidence. But true, false or somewhere between, here are the intriguing stories that have persisted:

Here is what we know:

Timeline -

1806: We know from Record Group 25, "Prison Records for the Main Prison at Nashville, Tennessee, 1831-1922," that Murrell was born in 1806, most likely in Williamson County, Tennessee.

1829: John Murrell had his first criminal conviction, for horse theft as a teenager and was branded with an "HT", flogged, and sentenced to six years in prison, being released in 1829.

1834: A decade in prison, starting in 1834, under the Auburn penitentiary system, of mandatory convict regimentation, through prison uniforms, lockstep, silence, and occasional solitary confinement, broke Murrell mentally.

In a deathbed confession, Murrell admitted to being guilty of most of the crimes charged against him except murder, to which he claimed to be "guiltless"

The Murrells were said to be an extremely handsome family. "John A. Murrell, especially, was remarkable for his manly beauty, curling auburn hair, worn long generally, decorated a classic head, and a prepossessing face, that would, said an observer, have drawn attention and been noticed among a thousand people ... His sister, Leanna Murrell, was remarkable for her beauty, and was the most skillful dancer of her day." (Columbia Herald and Mail, June 8, 1877).

Not only was John A. Murrell handsome but he was well educated. He possessed a brilliant mind and was able to adapt to almost any environment. He used these assets to pursue a life of crime that is unparalleled in Southern History. He was our Outlaw Cousin.

John learned to steal and at the age of 16, he robbed the family treasury of fifty dollars and left home for Nashville.

In Nashville, Murrell was recognized by one of his former victims from the Columbia inn. The man, however, was impressed by the young man's skill and asked Murrell to join him in a thieving adventure. This began his criminal career. Before he was 30, he was known as the great "Land Pirate" and was the most feared man along the Natchez Trace.

In 1826 Murrell was indicted for stealing a black mare from a widow in Williamson County, Tennessee. Tried in Davidson County, he was convicted and sentenced to be branded, whipped, and spend twelve months in jail. C. W. Nance was a young boy at the time. He witnessed and described the branding. He stated that Murrell was conducted to the prisoner's box, instructed to lay his hand on the railing while the sheriff "took from his pocket a piece of new hemp and bound Murrell's hand securely to the railing ... In a short while a big negro named Jeffry came in bringing a tinner's stove that looked like a lantern and placed it on the floor. Being anxious to see all that was going on, I climbed upon the railing close to Murrell. Mr. Horton, the sheriff, took from the little stove the branding iron, a long instrument, which looked very much like the soldering irons now used by tinners. He looked at the iron which was red hot and then put it on Murrell's hand. The skin fried like meat. Mr. Horton then untied Murrell's hand. Murrell, who had up to this time never moved, produced a white handerchief and wiped his hand several times. It was all over, and the sheriff took Murrell back to jail where he was yet to suffer punishment by being whipped and placed in the pillory." (From a story by Douglas Anderson in The Nashville Banner, March 20, 1921).

John Andrews Murrell stole some slaves from a Rev. Henning. Stewart was a friend of Hennings and agreed to try and find them. He ran accross Murrell on the trail and got into his good graces. Murrell began bragging about his crimes and Stewart would sneak write them down. Murrell even took him into his gang. Through the efforts of Stewart, Murrell was tried and convicted for stealing slaves. He went to the Tennessee State Prison in 1834. He came out of prison a broken sick man (T.B.). He came to Bledsoe Co. Tn. where he lived and died about a year later. He was buried in the Smyrna Cemetery abt 6 mi. north of Pikeville. A few days later a lady was going up past the cemetery to pick berries and came up to Murrell's grave and found that he had been disinterred and his head was cut off and was gone. A lot of speculation was going around about the whereabouts of his head. Apparently a couple of Drs. had done the deed and planned to study the head to find out what would make a man do the things that he did. They had a falling out and the head was displayed in various towns for a fee.

The largest of the oxbow lakes left by the meandering of the Mississippi River in Arkansas is Lake Chicot. On the upper end of the lake is an island called Stuart's Island. This island was once a stronghold for an outlaw band headed by John Murrell, one of the most deadly outlaws of the nineteenth century. His band of outlaws once numbered over 1,000 men. He was captured in Tennessee in 1834.

Murrell was best known as a slave thief. By his own admission, he stole more than one hundred. His procedure was to steal a slave, sell him, steal him again, and sell him again. This cycle continued until Murrell felt the slave might be recognized, at which time the poor slave was murdered. Murrell's motto was, "Dead men tell no tales."

Murrell loved fashionable clothes and beautiful horses. He was often seen in Nashville, Natchez, and New Orleans exquisitely dressed and riding fine horses. Usually, these possessions came from travelers he waylayed along the Natchez Trace. Reportedly, he robbed his victims, murdered them, and disposed of their bodies by slitting their stomachs, replacing their entrails with rocks, and sinking them in a nearby river or swamp.

The most ambitious of the Murrell schemes was his planned Negro uprising which would culminate with the overthrow of the city of New Orleans. The plans originated some time in early 1833.

Murrell had an outlaw army called "The Strikers" which met regularly at secret locations in Arkansas. There, the bandits finalized their plans. Originally, the uprising was to occur on Christmas Day, but was later moved to the Fourth of July, 1835.

Returning to plantation country, they convinced slaves to rebel rather than run away. Promising the Negroes freedom and power, they built a ghost army of black soldiers.

Murrell, however, was not to lead this army. In 1834, he was betrayed by one of his own lieutenants, Virgil A. Stewart. Convicted for the crime of slave stealing, he was sentenced to ten years in prison. From 1834 until 1844, he served his time in the Tennessee State Penitentiary.

With Murrell behind bars, it was relatively safe for Stewart to talk, and talk he did! He told of the planned revolt and by June of 1835, the entire Southwest was in a state of panic. From Nashville to New Orleans, nervous slave owners took precautions against the expected uprising.

Terror prevailed in sparsely populated Mississippi. On June 30, quickly armed and assembled white men seized several suspected Negroes. Under the lash, a black boy named Joe broke down. Others admitted that they had planned a revolt on July 4, because on the holiday slaves could assemble without being suspected. On July 2, the suspected slaves were hung.

The Nashville Banner reported that the conspirators planned, after first striking Madison County, 'to proceed thence, through the principal towns to Natchez, and then on to New Orleans - murdering all white men and ugly women - sparing the handsome ones and making wives of them - and plundering and burning as they went.' Thus, killing, and recruiting a black army, the entire South would fall under their controll. In such a dark dream the Southern states would be turned into a blazing, bleeding replica of the conditions which drove even Napoleon from San Domingo. In April, 1844, Murrell was released from prison. What happened to him then is shrouded in mystery.

Some say he repented, became a Christian, and lived the last years of his life as a Methodist in good standing, finally dying of tuberculosis he contracted while in prison.

Others say that while in prison, his mind cracked and he left jail as an imbecile, only to disappear; his final outcome unknown.

A third group argues that he went to Bledsoe County and worked for John M. Billingsley as a carpenter. He died at the home of Mr. Billingsley and was buried in a graveyard near old Symrna Church.

There is another story that goes with the third option. According to legend, Murrell discovered that there were some who wanted him dead, so he faked his own death. He found a man approximately his own size, murdered him, and buried him as John A. Murrell. Learning that his enemies were not satisfied and would exhume the body, he violated the grave, severed the man's head, and buried it in an unknown location. A short time later the open grave was discovered and the body was reinterred. Of course there was no way of proving that it was not Murrell.

In February, 1876, the Columbia Herald and Mail wrote, "To distinguish it the grave was dug at an angle of 45 degrees to the usual east and west line. It is still pointed out to curious strangers who visit the spot."

John was not the only scoundrel in the Murrell family. According to some historians, his brother, William, was only a notch better. During the 1820's, William taught a school at Salem Church on Yellow Creek in Houston County. William had a violent temper and one day, unjustly and unmercifully whipped a little girl named Maddin. The next morning the girl's mother met him at the school with an apron full of rocks. She stoned him, forcing him to wade the creek for safety. William left and never returned to the school.

____________

John Andrews Murrell, "The Reverend Devil" by Ross Phares:

John A. Murrel was born close to Jackson, Tennessee in the late 1700's and early 1800's. His dad was a Methodist preacher, and he was gone a lot. Legend has it that Murrel once said of his father that his father was an honest man, but John thought none the less of him for that. His mother taught him and the rest of her children to steal. His mother ran an inn, when he was a teen. He said that his mother was one of the true grit; she taught all her children to steal as soon as they could walk...and what ever they stole she would hide it for them and dared their father to touch them for stealing.

One time in Tennessee, when Murrel was a teen he got caught stealing horses. Back then in Tennessee it was serious to steal someone's horse. So he was tried for it and was branded with an "H.T." on his hand for horse thief. Murrel would wear gloves so no one would see the brand.

John liked to gamble and drink in Natchez and New Orleans. He claimed to be a preacher, but he really wasn't.

We are not sure exactly when, but it was still when John was pretty young; he started up a group of outlaws which he called the "clan." While he was pretending to be preaching, and the people were in church, he would send his clan out to rob the neighborhoods.

He and the clan members would shoot anyone who had money. Once, this young boy claimed to have lots of money, so they shot him. It turned out that he only had a dollar fifty. After that they would only shoot people if they knew that they had money.

John had been planning a slave up-rising for years. He soon thought to plan it on a holiday. A plantation owners wife overheard two little slave girls that were watching her baby say, "What ashame it is to kill this baby." The wife checked it out. She found out that Murrel was involved, from then on he was a marked man. People began to become suspicious.

John Murrel would always kill the people that he robbed. You know the saying "Dead men can't tell tales." Mr. Luther told us that one day Murrel and his clan stopped a man on his horse and they robbed him. They were about to kill him, and John told them to stop. They let the man ride away. Well, the man started wondering why they had done this. The man rode back to them and asked, "Why spare my life?" Murrel replied, "Ask your wife." The man returned home and asked his wife. She told him that John had once been shot, and she had nursed him back to health. Murrel saw a picture of her husband, and he recognized him that day. This was John's way of thanking the lady.

Years later, Murrel got into trouble again. He was sentenced to ten years in prison. When he got out, everyone had left him, his family, the clan, and all of his friends. They had either moved away or died. After that John was never seen again.

Still today, people look for Murrel's treasures. One of his favorite places to hide his stash was in a cave about seven miles from what is now Kisatchie. People say that a lot of satanic practices go on in those caves now. Sometimes you may get lucky and find a piece of gold or something that John had stolen, but no one really knows what happened to him or his treasures.

Thanks to Mr. Thomas Swafford of Tennessee, we have new information about John Murrell's last days. Murrell spent his last days in Pikeville, TN., about 50 miles from Chattanooga, TN. It seems that after Murrell's release from prison, he came to Pikeville to "drop out of sight". He had learned to be a blacksmith in prison, but due to tuberculosis, could not do this. Rumor has it that Murrell joined a church and lived a straight forward life after his move and even became a singer in the local church. Murrell died in Pikeville on November 3, 1844. After his death, grave robbers, supposedly two doctors, dug up the body and decapitated it. It seems that there was a reward for Murrell's skull. The presumably headless body still rests at the Smryna graveyard. A large rock slab used to cover the grave, but today a tombstone reading "John Murrell" marks the grave.

___________

John Murrell or Murrel was probably the most ruthless outlaw to ever roam the South. He never stole from a person and let them live. He only spared one man's life. Murrell didn't kill the man because the man's wife nursed Murrell back to health when he was shot.

Murrell was born in Jackson, Tennessee in the late 1700's. He started stealing horses when he was not much older than a boy. Back then, stealing horses was a serious crime. The judge called for him to have a "T" branded on his thumb for "thief". People said that he showed no emotion while the hot branding iron burned his skin.

John Murrell came to Louisiana because of the Neutral Strip, a strip of land in Louisiana owned by no one. It was between the Sabine River on the west and the Arroyo Hondo and the Calcasieu River on the east. There was no law enforcement in the Neutral Strip. Murrell could hide out there and not get caught. Sometimes he hung around saloons and bars in Natchez, Mississippi and New Orleans, Louisiana. He would also ride around old roads and rob settlers on their way to Texas. Once, Murrell was talking to a man he thought was rich. Murrell killed him so he could rob him. It turned out that the man had only $1.50.

Sometimes John Murrell preached. While he was preaching, some of his friends would rob the people who were listening to him while they where at church. This probably earned him the nickname "Reverend Devil."

After Murrell had been robbing people a while, he formed a clan of outlaws. They would meet in certain places and initiate new members. They had hand signs and hideouts. One hideout was a cave in the hills of Kisatchie. It was said to have three levels connected by tunnels. It used to be a Spanish gold mine. Some people still look for gold in it.

The way clan members could tell another member's house was they would have a black locust tree and a yucca plant in a certain location in their yards. The clan members would then stop at the house and rest or eat a meal. If a house had only one of the two plants, then it meant that the people in the house weren't clan members, but they were friendly.

One man who used to live close to Mount Carmel Church had a grandfather in Murrell's clan. He wanted to get out, and he did. He got sick and was in bed. All of a sudden, a stranger burst through the door and shot him. Legend has it that you didn't get out of the clan and live to tell about it.

Murrell and his clan tried to start a slave revolt. They planned for slaves to turn on their masters and kill them. Two slave girls were holding their master's baby and one of them said, "It sure will be a shame to kill this baby." The master's wife heard them say it. She couldn't get the girls to tell her anything more, so she called her son to come in and whip them until they talked. They accused someone else. He was hanged. A bunch of accusations followed and many people were hanged. Murrell's plan had not worked.

Finally, after years of robbing and killing, authorities caught up to Murrell. He served time in Tennessee State Prison at Nashville, then was released. From then on, no one knew what happened to him. Some say he went to Texas. It will probably always be a mystery.

_________

From "John A. Murrell, An Early Tennessee 'Terrorist'", by Lowell Kirk:

Governer Andrew Johnson of Tennessee compared the Know Nothing party members with the John A. Murrell gang. The Know-Nothings in the audience replied by shouting in unison, "It's a lie." When Johnson continued by stating, "Show me the dimension of a Know-Nothing, and I will show you a huge reptile, upon whose neck the foot of every honest man ought to be placed." (Tennessee, A Short History, p. 235) This was ten years after the death of John A. Murrell, yet by using this comparison, Andrew Johnson heard the cocking of pistols by the Know-Nothings in the crowd. In 1855 comparing someone to John A. Murrell could still bring out strong emotions.

In reality, John A. Murrell may have been nothing more than a charismatic organizer and leader of a band of small time thieves and slave stealers. Certainly many of the outrageous criminal acts associated with John A. Murrell were committed by men with no real link to the Murrell Klan. Certainly many other stories associated with the "Murrell Clan" were pure myth, legend and fiction. But this man came to be known as the Great Land Pirate and the leader of the notorious Murrell Clan. In the 182O's and 183O's people who lived and worked along the Natchez Trace, the Mississippi River and its tributaries and middle and west Tennessee lived in fear of contact with members of the "Murrell Klan," It was reputed to have included hundreds of members, if not thousands. Some of the leading political and business leaders of the time were reputed to have been members of the Murrell Clan. Many law enforcement officers were also reputed to be Murrell Clan members. In the early 19th century frontier the line between the lawless and the law-abiding citizens was not always easy to distinguish. John A. Murrell himself boasted that half of the Grand Council of his Mystic Clan was made up of "men of high standing and many of them in honorable and lucrative offices." It was reported that when he was about to make a deathbed confession, one of those members exclaimed, "Great God, John, don't give us all away!" (Botkin, p. 196)

The Grand Council of the Murrell Clan met, according to the legend, near a large sycamore tree in the thickest part of the forest in Arkansas, just across the Mississippi River from the town of Randolph in West Tennessee. It was at this "Grand Council Tree" where the Clansmen formed their dark plots and concocted their hellish plans. One of the more newsworthy episodes happened about twelve miles below Randolph. It shocked the whole country. B.A. Botkin described it with the following words.

"A most atrocious and diabolical wholesale murder and robbery had been committed on the Arkansas side. The crew of a flatboat had been murdered in cold blood, disemboweled, and thrown in the river, and the boat-stores appropriated among the perpetrators of the foul deed. The Murrell Clan was charged with the inhuman and devilish act. Public meetings were called in different parts of the country to devise means to rid the country and clear the woods of the Clan, and to bring to immediate punishment the murderers of the flatboat men. In Covington a campaign was formed to that end, under the command of Maj. Hockley and Grandville D. Searcey, and one, also formed in Randolph, under the command of Colonel Orville Shelby. A flatboat, suited to the purpose, was procured, and the expedition consisting of some eighty or a hundred men, well armed, with several day's rations, floated out from Randolph, and down to the landing where wholesale murder had been committed. Their place of destination was Shawnee Village, some six or more miles from the Mississippi, where the sheriff of the county resided. They were first to require of the sheriff to put the offenders under arrest and turn them over to be dealt with according to law. To the Shawnee Village the expedition moved in single file, along a tortuous trail through the thick cane and jungle, until within a few miles of the village, when a shrill whistle at the head of the column startled the whole line. Answered by the sharp click! click! click! of the cocking of the rifles in the hands of Clansmen. In ambush, to the right flank of the moving file, and within less than a dozen yards.

The chief of the Clan stepped out at the head of the expedition, and in a stentorian voice commanded the expedition to halt, saying:

"We have man for man; move forward another step and a rifle bullet will be sent through every man under your command."

A parley was had, when more than man for man of the Clansmen rose from their hiding places in the thick cane, with their guns at present. The expedition had fallen into a trap; the Clansmen had not been idle in finding out the movements against them across the river. Doubtless many of them had been in attendance at the meetings held for the purpose of their destruction. The movement had been a rash one, and nothing was left to be done but to adopt the axiom that "prudence is the better part of valor." The leaders of the expedition were permitted to communicate with the sheriff, who promised to do what he could in having the offenders brought to justice; but alas for Arkansas and justice! The Sheriff himself was thought to be in sympathy with the Clan. And law was in the hands of the Clansmen. The expedition retraced their steps. Had it not been so formidable and well known by the Clansmen, every member of it would have found his grave in the Arkansas swamp." (Quoted from Botkin, p. 214)

The preceding may have been an exaggeration. However, one record that can be somewhat trusted is the 1831-1842 Tennessee State Prison Record Book, which contains the following record.

"John A. Murrell was received in the Penitentiary August seventeenth one thousand eight hundred and thirty four; he is five feet ten inches and a half in height and weighs from one hundred and fifty eight to one hundred and seventy pounds; dark hair, blue eyes, long nose and much pitted with small pox; tolerably fair complexion; twenty-eight years of age. Born in Lunenburgh County, Virginia and brought up in Williamson County, Tennessee, his mother, wife and two children reside in the neighborhood of Denmark about nine miles from Jackson, Madison County, Tennessee. His wife's maiden name was Mangham; her connexion reside on the waters of South Harpeth, Williamson Co., Tenn. His brother Wm. S. Murrell, a Druggist, resides in Cincinnati, Ohio; he has another brother living in Sumpter County, S. Carolina; he has a scar on the middle joint of the finger next to the little finger of his left hand and one on the middle finger of the same hand; a scar on the inside of the end of the finger next the little finger of the right hand; has generally followed farming; was found guilty of Negro stealing at the Circuit Court of Madison County and sentenced to Ten years confinement in the jail and penitentiary House of the State of Tennessee." (1831-1842 Prison Record Book, Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville, TN)

According to the November 23, 1844 issue of the Tennessee Democrat, a Columbia newspaper, Murrell was released from prison in April 1844. He died of pulmonary consumption in Pikeville, Bledsoe County in November 1844. On his deathbed he reportedly acknowledged that he had - been guilty of almost every crime charged against him except murder. Regarding murder, he declared himself "guiltless."

While Murrell had been in prison he reportedly talked freely but regretfully of his crimes. Before his death he became a member of good standing in the Methodist Church. He was buried in a graveyard near old Smyrna Church. His grave was dug at an angle of 45 degrees to the usual east and west line. A few nights after the burial the grave was violated, and his head was found to be severed and taken away. The body was reburied and has remained undisturbed since the reburial.

Much of the story of John A Murrell's criminal career came from a book written by Virgil A. Stewart who had been a member of the clan. Stewart had many quotes from the great rogue, many of which he probably created himself. Murrell was born about 1804 in Virginia but very early in his life his father moved to Williamson County resided about a mile east from the Ridge meeting house, a Presbyterian Church on the Franklin and Lewisburg pike. In 1877 an observer wrote about this site:

"We stood, recently, on its bare and lonely summit. Tall, precipitous and wood hills bound it on the east; on the north the same range of hills, with their bare southern slopes, seamed with gullies and ravines and dotted with patches of sedge, and interspersed with thickets of briers and thorns, presents a bare and uninviting prospect. South, lies the basin of Rutherford Creek. Looking west and south spreads out a lovely smiling valley, on which rich and fruitful bosom repose the neighboring villages of Thompson Station and Spring Hill. The hill on which we stood for half a century has borne the name of the celebrated freebooter. A few scattered hearthstones and wild rose vines now alone mark the birthplace of John A. Murrell. The place where the celebrated bandit chief was born, and played around these scattered hearthstones, in boyish innocence (and prattled by his father's side, and bowed his curly head upon a fond mother's knee) looks dreary and desolate. It is a hill of broom sedge and thorny thickets, a covert and walk for foxes; like the birthplace of other great criminals, it seems to be avoided; as a habitation by man, and blighted by the hand of Providence, and made desolate. (Columbia Herald and Mail, 13 April 1877)

Now as to Murrell "bowing his curly head upon a fond mother's knee," the traditional legend goes like this. (I quoted from book The Devil's Backbone, p.240)

"Tradition, or fiction built high above tradition, presents the Murrell mother as a woman married to an itinerant preacher who only waited for his absence to make money as eager whore and avaricious thief. Preacher Murrell, it was said, left her to preach the gospel, fearful that otherwise he "would be after her all the time like a boar during the rutting season." When he was at home he tried to break her of "walking as she did, hips swinging and breasts undulating, and long thighs molding themselves against her skirt with each step." When her husband was away she made theft for her son easier because the traveler he robbed was "so weary from the sport she had given him on his bed...that he probably would have slept through an earthquake." (The Devil's Backbone, p. 240)

Back to records, in 1823 Murrell was fined by the court for "riot." In 1825, he was arrested for gambling. In 1826 he was tried for horse stealing twice. On the second time he was sentenced to a year in prison. According to Virgil A. Stewart, Murrell was a ready killer and robber who disposed of bodies by filling their abdominal cavities with stones and sinking the bodies in streams. Murrell loved fine clothes. "And his recollections of high times in whorehouses from Nashville by Natchez to New Orleans capture forever the picture of those pleasure places. He had no poetic concern with "still unravished brides of quietness." Still, his statement of frolic and "high fun with old Mother Surgick's girls almost creates an eternal frieze of wanton middle-American girls in the gay and obscene positions of harlotry. (The Devil's Backbone. p 241)

In 1845 the Police Gazette was established as a rowdy scandal sheet. Much of Virgil Stewart's book was rewritten and published by the Police Gazette, which is where the term, Great Western Land Pirate, was first applied to Murrell. All of the stories about Murrell agree that his slave stealing began in a small way. Murrell would promise a slave to lead him to freedom if the stolen Negro would let Murrell sell him once or twice on the way. After the stolen slave had been sold and stolen again so often that he might be recognizable, Murrell would kill him and dispose of the body by filling it with stones and dumping it in the river. Once he dealt with an entire slave family, mother father and children in such manner. Murrell obviously possessed some skills in organizing other rogues such as himself, building up his organization into what he called the Mystic Confederacy. He worked out deals with various 'fences' to sell his stolen loot, horses or slaves. According to Stewart, whose book was published in 1835, just before Murrell was sent to prison, Murrell planned a great slave rebellion in the southwest. Then in the panic that was sure to occur, Murrell calculated that he and his associates could loot plantations and whole towns.

Obviously due to the intense Southern fears of the current abolitionist movement of the time, this plan as revealed by Stewart stirred up memories of the Nat Turner rebellion that had occurred in Virginia in 1831. Murrell, of course, was already on his way to jail for ten years. But on June 30 a vigilante organization seized several suspected Negro rebels who admitted, under beatings and lashings that they had planned a revolt for July 4. On July 2, the suspected slaves were hung. Shortly thereafter two white men were seized. Joshua Cotton and William Saunders, both "steam doctors" of anew therapies then in vogue, were charged in Mississippi with involvement in this Murrell backed slave insurrection.

Newspapers in towns from Nashville to Natchez told of sensational and frightening stories of the revolt. Joshua Cotton admitted that he was a member of Murrell's gang. He implicated some other white men from Hinds County and Warren County, Mississippi and declared that the planned rebellion "embraced the whole slave region from Maryland to Louisiana and contemplated the total destruction of the white population of all the slave states." Cotton and Saunders were sentenced to be hanged by the vigilante jury. Saunders claimed to be innocent until the rope on a makeshift gallows silenced him forever. But Cotton publicly confirmed his guilt and warned the people to beware. He named other men. It seems unlikely that Murrell ever had planned such an insurrection, but Mississippi saw much violence tear through the state before the fear of a slave insurrection subsided. Terror and indignation at abolitionists rode the roads between Natchez and Nashville. It was the time when lynch law was the answer to the mostly unfounded fears of a slave insurrection.

The Murrell Clan's reputation for far reaching terrorism was obviously expanded greatly by the exaggerations first published by Virgil Stewart in 1835. The sensational tabloid press, especially the Police Gazette, further enhanced the legend of the Murrell Clan. But it seems to me that the connection of the Murrell Clan to a widespread fear of a slave insurrection deserves so much of the credit for turning a small time rogue and slave stealer into the legendary big time terrorist leader. In the decade of the 183Os, Abolitionism was considered to be the ultimate evil in the slave-holding South. John A. Murrell lived less than forty years. The last ten years he spent in prison. In the last seven months of his life he became a member in good standing with the Methodist Church as he engaged in the trade of carpentry. As Shakespeare once wrote of men, the good that men do is often interred with their bones. Only the evil lives after them. In John A. Murrell's case, it was afar more evil reputation than even he deserved. -Lowell Kirk 2002

INFORMATION FROM GARY MATHIS:

His father and uncle, Drury, posted bond for him.

From the 1831-1842 Prison Record Book, Tennessee State Archives) When he was released (April 18, 1844):

John A. Murrell's Cell---While inspecting the records of the penitentiary yesterday, records grown musty and yellow with age, an American reporter came across an entry concerning a noted individual, whose name, fifty years ago, was a terror, not only to Middle Tennessee, but to the entire State. The individual referred to was John A. Murrell, and the entry that startled the reporter, as he nervously clutched the page, was the notation made on the records when Murrell was received at the penitentiary in 1834 for stealing a negro in Madison County. The entry, as it appears on the penitentiary records, is as follows: "John A. Murrell was received in the penitentiary August 17, 1834. He is five feet ten inches and a half in height, and weight from 158 to 170 pounds, dark hair, blue eyes, long nose and much pitted with the small- pox, tolerably fair complexion, twenty-eight years of age. Born in Lunenburg County, Virginia, and brought up in Williamson County, Tennessee. His mother, wife and two children reside in the neighborhood of Denmark, about nine miles from Jackson, Madison County, Tennessee. His wife's maiden name was Manghan. Her connections reside on the waters of South Harpeth, Williamson County, Tennessee. His brother, William S. Murrell, a druggist, resides in Cincinnati, Ohio. He has another brother living in Sumsterville, S.C. He has a scar on the middle joint of the finger next the little finger of the right hand. Has generally followed farming. Was found guilty of Negro stealing at the Circuit Court of Madison County and sentenced to ten years confinement in the jail and penitentiary house of the State of Tennessee." On the margin of the record is indorsed: "John A. Murrell was delivered to J.S. Lyon, Sheriff of Madison County, 9th April 1837. See order of Court of Errors and Appeals, at Jackson, filed with convict record, 1834." And below this appears the entry: "Returned April 26, 1837, by order of Court of Appeals." Murrell was discharged at the expiration of his time, but no entry appears on the penitentiary books showing the date of his discharge. While an inmate at the penitentiary, Murrell learned the blacksmith trade and followed it during the time of his imprisonment. He occupied the second cell from the entrance in wing No. 2. The cell was inspected by the reporter, but any marks of Murrell's occupancy that may have existed have disappeared beneath the white-wash that has been applied scores of times since Tennessee's noted highwayman called the cell his own nearly fifty years ago. ---Nashville American.

John Andrews Murrell

in the Biography & Genealogy Master Index (BGMI)

Name: John Andrews Murrell

Birth Year: 1805

Death Year: 1844

Title: Biography Index

Title Pen: 0269

Title Code: BioIn 12

Accession Number: 3309973

Source:

Biography Index. A cumulative index to biographical material in books and magazines. Volume 12: September, 1979-August, 1982. New York: H.W. Wilson Co., 1983. (BioIn 12)

Name: John Andrews Murrell

Birth Year: 1806

Death Year: 1844

Title: American National Biography

Title Pen: 3989

Title Code: AmNatBi

Accession Number: 3309974

Source:

American National Biography. 24 volumes. Edited by John A. Garraty and Mark C. Carnes. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. (AmNatBi)

Still today, people look for Murrel's treasures. One of his favorite places to hide his stash was in a cave about seven miles from what is now Kisatchie. People say that a lot of satanic practices go on in those caves now. Sometimes you may get lucky and find a piece of gold or something that John had stolen, but no one really knows what happened to him or his treasures. Thanks to Mr. Thomas Swafford of Tennessee, we have new information about John Murrell's last days. Murrell spent his last days in Pikeville, TN., about 50 miles from Chattanooga, TN. It seems that after Murrell's release from prison, he came to Pikeville to "drop out of sight". He had learned to be a blacksmith in prison, but due to tuberculosis, could not do this. Rumor has it that Murrell joined a church and lived a straight forward life after his move and even became a singer in the local church. Murrell died in Pikeville on November 3, 1844. After his death, grave robbers, supposedly two doctors, dug up the body and decapitated it. It seems that there was a reward for Murrell's skull. The presumably headless body still rests at the Smryna graveyard. A large rock slab used to cover the grave, but today a tombstone reading "John Murrell" marks the grave.

His body was buried with him facing West.

While living in Tennessee, future U.S. Senator Senator Joseph Williams Chalmers earned notice as the defense attorney for a well-known criminal John Andrews Murrell, also known as "The Land Pirate."

Son of Rev. Jeffrey Gilliam Murrell (1738 Lunenburg, VA - 11/25/1824 Williamson County, TN) and Zelphia Andrews Murrell.

On March 5, 1829 in Maury County, TN, married Elizabeth Mangham (1810 South Harpeth, Williamson County, TN - March 5, 1891 Chester County, Tennessee)

THE PULASKI CITIZEN

March 26, 1885

The Widow of Jno. A. Murrell.

"The widow of the bandit, John Andrews Murrell, is a resident of the Henderson section of Chester County. She is a kind, amiable old lady and is highly respected in the neighborhood." - Lexington Progress

From a personal acquaintance with the lady above mentioned, we are prepared to indorse as a truth the statement of the Progress. She is, indeed, a woman possessing in an eminent degree the qualities attributed. The writer has had many conversations with her, but in no instance did she ever refer to her husband or his notorious deeds. On that subject she has ever remained silent, and every effort to get her to speak of him or his deeds fail. It is believed that she possesses important papers concerning the life of her husband, and may, sometime in the near future, place them in the hands of some trusted person as data for a truthful history of the man whose deeds are memorable in the history and tradition of this section.

Mrs. Jno. A. Murrell is a rapid talker, and has a very retentive memory from which she produces many interesting incidents of more than half a century ago which are interwoven in our local and state history. Her descendants are living principally in Chester and Hardeman counties and are all good citizens. She has no permanent home, but lives among her children and other relatives. After Murrell's death she married a second time to Mr. Bland, who died several years ago. Time has whitened her locks and furrowed her cheek, but upon the aged countenance clusters the light of a benignant soul. Despite age, her eyes retain their sight, and when in animated conversation they sparkle with as much brilliancy as those of youth. We do not know her exact age, but she is at least an octogenarian. Full of life, energy, yielding not to the pressure of years, this kind old lady moves toward the evening horizon of life, affable, generous and unostentatious. - Tribune and Sun.

CHILDREN:

1. Leanna E. Jane Murrell (abt. 1829 TN-____). She married William T. Davis on April 15, 1853 in Madison County, TN.

2. Jeffrey Murrell (1830, Denmark, Madison County, TN-____)

3. John Andrews Murrell, Jr. (1834 Wayne County, TN - February 15, 1865 Pikesville, Bledsoe County, Tennessee)

4. Arthusy Madeline Murrell (1833 Pikeville, TN - 1891 Henderson, McNairy County, TN) married Robert B. Bland (1825 Wilson County, TN - 1869 McNairy County, TN) and they had the following children: Sarah L Bland (1849–____) she married William Gilding; John I. Bland (3/21/1851 TN– 12/24/1925 TN) [He married first Edna L Corley(1849–1915) and had children Lula Belle Bland (1889–1990) and he married second Anna Bell Elder (1864–____) and had William Cleveland Bland (1887–1967) and married third Mary J Bland (1856–1882)]; Mary Elizabeth Bland (1853 McNairy Co, TN–____); Rachel Ann Penelope Bland (Abt 1859–1895 McNairy Co, TN); Robert Allen Bland (1861–11/22/1939 Jackson, Madison Co, TN); Henry J Bland (1863–____); Lavanda D Bland (1866–1929) [She married Andrew Jack Campbell Jr (1854–1918) and had children Robert Campbell (1892–___), Florence Leona Campbell (1896–1991), John Campbell (1898–____), Edith Ellen Campbell (1904–1989), Purrie Beatrice Campbell (1906–1982), Bertha Campbell (1908–____)]; Nancy C. Bland (1868–____); Virginia Ophelia Bland (1874-1955) and Julie or Juley Bland (Abt 1878 TN–____).

5. Missouri F. Murrell (6/24/1833 Pikeville,TN - 4/21/1873 McNairy County, TN- burial Haltoms Chapel Cemetery, Chester Co, Tennessee). She married Benjamin Thomas Hardy (5/18/1828 Pittsylvania Co., VA-___) on April 21, 1853 in Madison County, Tn and they had the following children: James T. Hardy (b. ABT 1854 Tennessee); Joseph H. Hardy (b. ABT 1856 in Tennessee); John G. T. Hardy (b. ABT 1859 in Tennessee); Nancy F. Hardy (b. 24 OCT 1860 in McNairy Co, Tennessee; Burial- Haltoms Chapel Cemetery, Chester Co, Tennessee ) and William S. Hardy (b. ABT 1863 in McNairy Co, Tennessee)

John's father, Jeffery Murrell, brother of Thomas Murrell (1737 Goochland, Virginia-26 MAY 1826 Dickson, Dickson, Tennessee), moved to Middle Tennessee and he purchased 146 acres in Williamson County, a short distance from Dickson County. His land adjoined that of another brother, Drury, and was near his father-in-law, Mark Andrews, son of William A. Andrews, Sr.

John Andrews Murrell's Uncle Thomas' children all made respectable citizens, but Jeffery was not quite as fortunate. It is Jeffery's children that are "Our Outlaw Cousins."

Jeffery was an itinerant preacher and traveled throughout the countryside preaching the Gospel of Christ. His reputation was spotless, but his high morals were not shared by John Andrews. Murrell.

There is a book (something like 'Rouges and Vagabonds') which has an account of John Andrews Murrell.

According to family members, John Andrews Murrell has been much maligned by the sensational phamplet of Virgil Stewart in 1835 (The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture) and still later by the fabricated tale of Robert M. Coates. John's father, Jeffrey, was a Methodist minister, and his son John Andrews Murrell was found guilty of being a horse thief and later of harboring a slave. They assert that virtually all other stories about him are unsupported by facts or evidence. But true, false or somewhere between, here are the intriguing stories that have persisted:

Here is what we know:

Timeline -

1806: We know from Record Group 25, "Prison Records for the Main Prison at Nashville, Tennessee, 1831-1922," that Murrell was born in 1806, most likely in Williamson County, Tennessee.

1829: John Murrell had his first criminal conviction, for horse theft as a teenager and was branded with an "HT", flogged, and sentenced to six years in prison, being released in 1829.

1834: A decade in prison, starting in 1834, under the Auburn penitentiary system, of mandatory convict regimentation, through prison uniforms, lockstep, silence, and occasional solitary confinement, broke Murrell mentally.

In a deathbed confession, Murrell admitted to being guilty of most of the crimes charged against him except murder, to which he claimed to be "guiltless"

The Murrells were said to be an extremely handsome family. "John A. Murrell, especially, was remarkable for his manly beauty, curling auburn hair, worn long generally, decorated a classic head, and a prepossessing face, that would, said an observer, have drawn attention and been noticed among a thousand people ... His sister, Leanna Murrell, was remarkable for her beauty, and was the most skillful dancer of her day." (Columbia Herald and Mail, June 8, 1877).

Not only was John A. Murrell handsome but he was well educated. He possessed a brilliant mind and was able to adapt to almost any environment. He used these assets to pursue a life of crime that is unparalleled in Southern History. He was our Outlaw Cousin.

John learned to steal and at the age of 16, he robbed the family treasury of fifty dollars and left home for Nashville.

In Nashville, Murrell was recognized by one of his former victims from the Columbia inn. The man, however, was impressed by the young man's skill and asked Murrell to join him in a thieving adventure. This began his criminal career. Before he was 30, he was known as the great "Land Pirate" and was the most feared man along the Natchez Trace.

In 1826 Murrell was indicted for stealing a black mare from a widow in Williamson County, Tennessee. Tried in Davidson County, he was convicted and sentenced to be branded, whipped, and spend twelve months in jail. C. W. Nance was a young boy at the time. He witnessed and described the branding. He stated that Murrell was conducted to the prisoner's box, instructed to lay his hand on the railing while the sheriff "took from his pocket a piece of new hemp and bound Murrell's hand securely to the railing ... In a short while a big negro named Jeffry came in bringing a tinner's stove that looked like a lantern and placed it on the floor. Being anxious to see all that was going on, I climbed upon the railing close to Murrell. Mr. Horton, the sheriff, took from the little stove the branding iron, a long instrument, which looked very much like the soldering irons now used by tinners. He looked at the iron which was red hot and then put it on Murrell's hand. The skin fried like meat. Mr. Horton then untied Murrell's hand. Murrell, who had up to this time never moved, produced a white handerchief and wiped his hand several times. It was all over, and the sheriff took Murrell back to jail where he was yet to suffer punishment by being whipped and placed in the pillory." (From a story by Douglas Anderson in The Nashville Banner, March 20, 1921).

John Andrews Murrell stole some slaves from a Rev. Henning. Stewart was a friend of Hennings and agreed to try and find them. He ran accross Murrell on the trail and got into his good graces. Murrell began bragging about his crimes and Stewart would sneak write them down. Murrell even took him into his gang. Through the efforts of Stewart, Murrell was tried and convicted for stealing slaves. He went to the Tennessee State Prison in 1834. He came out of prison a broken sick man (T.B.). He came to Bledsoe Co. Tn. where he lived and died about a year later. He was buried in the Smyrna Cemetery abt 6 mi. north of Pikeville. A few days later a lady was going up past the cemetery to pick berries and came up to Murrell's grave and found that he had been disinterred and his head was cut off and was gone. A lot of speculation was going around about the whereabouts of his head. Apparently a couple of Drs. had done the deed and planned to study the head to find out what would make a man do the things that he did. They had a falling out and the head was displayed in various towns for a fee.

The largest of the oxbow lakes left by the meandering of the Mississippi River in Arkansas is Lake Chicot. On the upper end of the lake is an island called Stuart's Island. This island was once a stronghold for an outlaw band headed by John Murrell, one of the most deadly outlaws of the nineteenth century. His band of outlaws once numbered over 1,000 men. He was captured in Tennessee in 1834.

Murrell was best known as a slave thief. By his own admission, he stole more than one hundred. His procedure was to steal a slave, sell him, steal him again, and sell him again. This cycle continued until Murrell felt the slave might be recognized, at which time the poor slave was murdered. Murrell's motto was, "Dead men tell no tales."

Murrell loved fashionable clothes and beautiful horses. He was often seen in Nashville, Natchez, and New Orleans exquisitely dressed and riding fine horses. Usually, these possessions came from travelers he waylayed along the Natchez Trace. Reportedly, he robbed his victims, murdered them, and disposed of their bodies by slitting their stomachs, replacing their entrails with rocks, and sinking them in a nearby river or swamp.

The most ambitious of the Murrell schemes was his planned Negro uprising which would culminate with the overthrow of the city of New Orleans. The plans originated some time in early 1833.

Murrell had an outlaw army called "The Strikers" which met regularly at secret locations in Arkansas. There, the bandits finalized their plans. Originally, the uprising was to occur on Christmas Day, but was later moved to the Fourth of July, 1835.

Returning to plantation country, they convinced slaves to rebel rather than run away. Promising the Negroes freedom and power, they built a ghost army of black soldiers.

Murrell, however, was not to lead this army. In 1834, he was betrayed by one of his own lieutenants, Virgil A. Stewart. Convicted for the crime of slave stealing, he was sentenced to ten years in prison. From 1834 until 1844, he served his time in the Tennessee State Penitentiary.

With Murrell behind bars, it was relatively safe for Stewart to talk, and talk he did! He told of the planned revolt and by June of 1835, the entire Southwest was in a state of panic. From Nashville to New Orleans, nervous slave owners took precautions against the expected uprising.

Terror prevailed in sparsely populated Mississippi. On June 30, quickly armed and assembled white men seized several suspected Negroes. Under the lash, a black boy named Joe broke down. Others admitted that they had planned a revolt on July 4, because on the holiday slaves could assemble without being suspected. On July 2, the suspected slaves were hung.

The Nashville Banner reported that the conspirators planned, after first striking Madison County, 'to proceed thence, through the principal towns to Natchez, and then on to New Orleans - murdering all white men and ugly women - sparing the handsome ones and making wives of them - and plundering and burning as they went.' Thus, killing, and recruiting a black army, the entire South would fall under their controll. In such a dark dream the Southern states would be turned into a blazing, bleeding replica of the conditions which drove even Napoleon from San Domingo. In April, 1844, Murrell was released from prison. What happened to him then is shrouded in mystery.

Some say he repented, became a Christian, and lived the last years of his life as a Methodist in good standing, finally dying of tuberculosis he contracted while in prison.

Others say that while in prison, his mind cracked and he left jail as an imbecile, only to disappear; his final outcome unknown.

A third group argues that he went to Bledsoe County and worked for John M. Billingsley as a carpenter. He died at the home of Mr. Billingsley and was buried in a graveyard near old Symrna Church.

There is another story that goes with the third option. According to legend, Murrell discovered that there were some who wanted him dead, so he faked his own death. He found a man approximately his own size, murdered him, and buried him as John A. Murrell. Learning that his enemies were not satisfied and would exhume the body, he violated the grave, severed the man's head, and buried it in an unknown location. A short time later the open grave was discovered and the body was reinterred. Of course there was no way of proving that it was not Murrell.

In February, 1876, the Columbia Herald and Mail wrote, "To distinguish it the grave was dug at an angle of 45 degrees to the usual east and west line. It is still pointed out to curious strangers who visit the spot."

John was not the only scoundrel in the Murrell family. According to some historians, his brother, William, was only a notch better. During the 1820's, William taught a school at Salem Church on Yellow Creek in Houston County. William had a violent temper and one day, unjustly and unmercifully whipped a little girl named Maddin. The next morning the girl's mother met him at the school with an apron full of rocks. She stoned him, forcing him to wade the creek for safety. William left and never returned to the school.

____________

John Andrews Murrell, "The Reverend Devil" by Ross Phares:

John A. Murrel was born close to Jackson, Tennessee in the late 1700's and early 1800's. His dad was a Methodist preacher, and he was gone a lot. Legend has it that Murrel once said of his father that his father was an honest man, but John thought none the less of him for that. His mother taught him and the rest of her children to steal. His mother ran an inn, when he was a teen. He said that his mother was one of the true grit; she taught all her children to steal as soon as they could walk...and what ever they stole she would hide it for them and dared their father to touch them for stealing.

One time in Tennessee, when Murrel was a teen he got caught stealing horses. Back then in Tennessee it was serious to steal someone's horse. So he was tried for it and was branded with an "H.T." on his hand for horse thief. Murrel would wear gloves so no one would see the brand.

John liked to gamble and drink in Natchez and New Orleans. He claimed to be a preacher, but he really wasn't.

We are not sure exactly when, but it was still when John was pretty young; he started up a group of outlaws which he called the "clan." While he was pretending to be preaching, and the people were in church, he would send his clan out to rob the neighborhoods.

He and the clan members would shoot anyone who had money. Once, this young boy claimed to have lots of money, so they shot him. It turned out that he only had a dollar fifty. After that they would only shoot people if they knew that they had money.

John had been planning a slave up-rising for years. He soon thought to plan it on a holiday. A plantation owners wife overheard two little slave girls that were watching her baby say, "What ashame it is to kill this baby." The wife checked it out. She found out that Murrel was involved, from then on he was a marked man. People began to become suspicious.

John Murrel would always kill the people that he robbed. You know the saying "Dead men can't tell tales." Mr. Luther told us that one day Murrel and his clan stopped a man on his horse and they robbed him. They were about to kill him, and John told them to stop. They let the man ride away. Well, the man started wondering why they had done this. The man rode back to them and asked, "Why spare my life?" Murrel replied, "Ask your wife." The man returned home and asked his wife. She told him that John had once been shot, and she had nursed him back to health. Murrel saw a picture of her husband, and he recognized him that day. This was John's way of thanking the lady.

Years later, Murrel got into trouble again. He was sentenced to ten years in prison. When he got out, everyone had left him, his family, the clan, and all of his friends. They had either moved away or died. After that John was never seen again.

Still today, people look for Murrel's treasures. One of his favorite places to hide his stash was in a cave about seven miles from what is now Kisatchie. People say that a lot of satanic practices go on in those caves now. Sometimes you may get lucky and find a piece of gold or something that John had stolen, but no one really knows what happened to him or his treasures.

Thanks to Mr. Thomas Swafford of Tennessee, we have new information about John Murrell's last days. Murrell spent his last days in Pikeville, TN., about 50 miles from Chattanooga, TN. It seems that after Murrell's release from prison, he came to Pikeville to "drop out of sight". He had learned to be a blacksmith in prison, but due to tuberculosis, could not do this. Rumor has it that Murrell joined a church and lived a straight forward life after his move and even became a singer in the local church. Murrell died in Pikeville on November 3, 1844. After his death, grave robbers, supposedly two doctors, dug up the body and decapitated it. It seems that there was a reward for Murrell's skull. The presumably headless body still rests at the Smryna graveyard. A large rock slab used to cover the grave, but today a tombstone reading "John Murrell" marks the grave.

___________

John Murrell or Murrel was probably the most ruthless outlaw to ever roam the South. He never stole from a person and let them live. He only spared one man's life. Murrell didn't kill the man because the man's wife nursed Murrell back to health when he was shot.

Murrell was born in Jackson, Tennessee in the late 1700's. He started stealing horses when he was not much older than a boy. Back then, stealing horses was a serious crime. The judge called for him to have a "T" branded on his thumb for "thief". People said that he showed no emotion while the hot branding iron burned his skin.

John Murrell came to Louisiana because of the Neutral Strip, a strip of land in Louisiana owned by no one. It was between the Sabine River on the west and the Arroyo Hondo and the Calcasieu River on the east. There was no law enforcement in the Neutral Strip. Murrell could hide out there and not get caught. Sometimes he hung around saloons and bars in Natchez, Mississippi and New Orleans, Louisiana. He would also ride around old roads and rob settlers on their way to Texas. Once, Murrell was talking to a man he thought was rich. Murrell killed him so he could rob him. It turned out that the man had only $1.50.

Sometimes John Murrell preached. While he was preaching, some of his friends would rob the people who were listening to him while they where at church. This probably earned him the nickname "Reverend Devil."

After Murrell had been robbing people a while, he formed a clan of outlaws. They would meet in certain places and initiate new members. They had hand signs and hideouts. One hideout was a cave in the hills of Kisatchie. It was said to have three levels connected by tunnels. It used to be a Spanish gold mine. Some people still look for gold in it.

The way clan members could tell another member's house was they would have a black locust tree and a yucca plant in a certain location in their yards. The clan members would then stop at the house and rest or eat a meal. If a house had only one of the two plants, then it meant that the people in the house weren't clan members, but they were friendly.

One man who used to live close to Mount Carmel Church had a grandfather in Murrell's clan. He wanted to get out, and he did. He got sick and was in bed. All of a sudden, a stranger burst through the door and shot him. Legend has it that you didn't get out of the clan and live to tell about it.

Murrell and his clan tried to start a slave revolt. They planned for slaves to turn on their masters and kill them. Two slave girls were holding their master's baby and one of them said, "It sure will be a shame to kill this baby." The master's wife heard them say it. She couldn't get the girls to tell her anything more, so she called her son to come in and whip them until they talked. They accused someone else. He was hanged. A bunch of accusations followed and many people were hanged. Murrell's plan had not worked.

Finally, after years of robbing and killing, authorities caught up to Murrell. He served time in Tennessee State Prison at Nashville, then was released. From then on, no one knew what happened to him. Some say he went to Texas. It will probably always be a mystery.

_________

From "John A. Murrell, An Early Tennessee 'Terrorist'", by Lowell Kirk:

Governer Andrew Johnson of Tennessee compared the Know Nothing party members with the John A. Murrell gang. The Know-Nothings in the audience replied by shouting in unison, "It's a lie." When Johnson continued by stating, "Show me the dimension of a Know-Nothing, and I will show you a huge reptile, upon whose neck the foot of every honest man ought to be placed." (Tennessee, A Short History, p. 235) This was ten years after the death of John A. Murrell, yet by using this comparison, Andrew Johnson heard the cocking of pistols by the Know-Nothings in the crowd. In 1855 comparing someone to John A. Murrell could still bring out strong emotions.

In reality, John A. Murrell may have been nothing more than a charismatic organizer and leader of a band of small time thieves and slave stealers. Certainly many of the outrageous criminal acts associated with John A. Murrell were committed by men with no real link to the Murrell Klan. Certainly many other stories associated with the "Murrell Clan" were pure myth, legend and fiction. But this man came to be known as the Great Land Pirate and the leader of the notorious Murrell Clan. In the 182O's and 183O's people who lived and worked along the Natchez Trace, the Mississippi River and its tributaries and middle and west Tennessee lived in fear of contact with members of the "Murrell Klan," It was reputed to have included hundreds of members, if not thousands. Some of the leading political and business leaders of the time were reputed to have been members of the Murrell Clan. Many law enforcement officers were also reputed to be Murrell Clan members. In the early 19th century frontier the line between the lawless and the law-abiding citizens was not always easy to distinguish. John A. Murrell himself boasted that half of the Grand Council of his Mystic Clan was made up of "men of high standing and many of them in honorable and lucrative offices." It was reported that when he was about to make a deathbed confession, one of those members exclaimed, "Great God, John, don't give us all away!" (Botkin, p. 196)

The Grand Council of the Murrell Clan met, according to the legend, near a large sycamore tree in the thickest part of the forest in Arkansas, just across the Mississippi River from the town of Randolph in West Tennessee. It was at this "Grand Council Tree" where the Clansmen formed their dark plots and concocted their hellish plans. One of the more newsworthy episodes happened about twelve miles below Randolph. It shocked the whole country. B.A. Botkin described it with the following words.

"A most atrocious and diabolical wholesale murder and robbery had been committed on the Arkansas side. The crew of a flatboat had been murdered in cold blood, disemboweled, and thrown in the river, and the boat-stores appropriated among the perpetrators of the foul deed. The Murrell Clan was charged with the inhuman and devilish act. Public meetings were called in different parts of the country to devise means to rid the country and clear the woods of the Clan, and to bring to immediate punishment the murderers of the flatboat men. In Covington a campaign was formed to that end, under the command of Maj. Hockley and Grandville D. Searcey, and one, also formed in Randolph, under the command of Colonel Orville Shelby. A flatboat, suited to the purpose, was procured, and the expedition consisting of some eighty or a hundred men, well armed, with several day's rations, floated out from Randolph, and down to the landing where wholesale murder had been committed. Their place of destination was Shawnee Village, some six or more miles from the Mississippi, where the sheriff of the county resided. They were first to require of the sheriff to put the offenders under arrest and turn them over to be dealt with according to law. To the Shawnee Village the expedition moved in single file, along a tortuous trail through the thick cane and jungle, until within a few miles of the village, when a shrill whistle at the head of the column startled the whole line. Answered by the sharp click! click! click! of the cocking of the rifles in the hands of Clansmen. In ambush, to the right flank of the moving file, and within less than a dozen yards.

The chief of the Clan stepped out at the head of the expedition, and in a stentorian voice commanded the expedition to halt, saying:

"We have man for man; move forward another step and a rifle bullet will be sent through every man under your command."

A parley was had, when more than man for man of the Clansmen rose from their hiding places in the thick cane, with their guns at present. The expedition had fallen into a trap; the Clansmen had not been idle in finding out the movements against them across the river. Doubtless many of them had been in attendance at the meetings held for the purpose of their destruction. The movement had been a rash one, and nothing was left to be done but to adopt the axiom that "prudence is the better part of valor." The leaders of the expedition were permitted to communicate with the sheriff, who promised to do what he could in having the offenders brought to justice; but alas for Arkansas and justice! The Sheriff himself was thought to be in sympathy with the Clan. And law was in the hands of the Clansmen. The expedition retraced their steps. Had it not been so formidable and well known by the Clansmen, every member of it would have found his grave in the Arkansas swamp." (Quoted from Botkin, p. 214)

The preceding may have been an exaggeration. However, one record that can be somewhat trusted is the 1831-1842 Tennessee State Prison Record Book, which contains the following record.

"John A. Murrell was received in the Penitentiary August seventeenth one thousand eight hundred and thirty four; he is five feet ten inches and a half in height and weighs from one hundred and fifty eight to one hundred and seventy pounds; dark hair, blue eyes, long nose and much pitted with small pox; tolerably fair complexion; twenty-eight years of age. Born in Lunenburgh County, Virginia and brought up in Williamson County, Tennessee, his mother, wife and two children reside in the neighborhood of Denmark about nine miles from Jackson, Madison County, Tennessee. His wife's maiden name was Mangham; her connexion reside on the waters of South Harpeth, Williamson Co., Tenn. His brother Wm. S. Murrell, a Druggist, resides in Cincinnati, Ohio; he has another brother living in Sumpter County, S. Carolina; he has a scar on the middle joint of the finger next to the little finger of his left hand and one on the middle finger of the same hand; a scar on the inside of the end of the finger next the little finger of the right hand; has generally followed farming; was found guilty of Negro stealing at the Circuit Court of Madison County and sentenced to Ten years confinement in the jail and penitentiary House of the State of Tennessee." (1831-1842 Prison Record Book, Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville, TN)

According to the November 23, 1844 issue of the Tennessee Democrat, a Columbia newspaper, Murrell was released from prison in April 1844. He died of pulmonary consumption in Pikeville, Bledsoe County in November 1844. On his deathbed he reportedly acknowledged that he had - been guilty of almost every crime charged against him except murder. Regarding murder, he declared himself "guiltless."

While Murrell had been in prison he reportedly talked freely but regretfully of his crimes. Before his death he became a member of good standing in the Methodist Church. He was buried in a graveyard near old Smyrna Church. His grave was dug at an angle of 45 degrees to the usual east and west line. A few nights after the burial the grave was violated, and his head was found to be severed and taken away. The body was reburied and has remained undisturbed since the reburial.

Much of the story of John A Murrell's criminal career came from a book written by Virgil A. Stewart who had been a member of the clan. Stewart had many quotes from the great rogue, many of which he probably created himself. Murrell was born about 1804 in Virginia but very early in his life his father moved to Williamson County resided about a mile east from the Ridge meeting house, a Presbyterian Church on the Franklin and Lewisburg pike. In 1877 an observer wrote about this site:

"We stood, recently, on its bare and lonely summit. Tall, precipitous and wood hills bound it on the east; on the north the same range of hills, with their bare southern slopes, seamed with gullies and ravines and dotted with patches of sedge, and interspersed with thickets of briers and thorns, presents a bare and uninviting prospect. South, lies the basin of Rutherford Creek. Looking west and south spreads out a lovely smiling valley, on which rich and fruitful bosom repose the neighboring villages of Thompson Station and Spring Hill. The hill on which we stood for half a century has borne the name of the celebrated freebooter. A few scattered hearthstones and wild rose vines now alone mark the birthplace of John A. Murrell. The place where the celebrated bandit chief was born, and played around these scattered hearthstones, in boyish innocence (and prattled by his father's side, and bowed his curly head upon a fond mother's knee) looks dreary and desolate. It is a hill of broom sedge and thorny thickets, a covert and walk for foxes; like the birthplace of other great criminals, it seems to be avoided; as a habitation by man, and blighted by the hand of Providence, and made desolate. (Columbia Herald and Mail, 13 April 1877)

Now as to Murrell "bowing his curly head upon a fond mother's knee," the traditional legend goes like this. (I quoted from book The Devil's Backbone, p.240)

"Tradition, or fiction built high above tradition, presents the Murrell mother as a woman married to an itinerant preacher who only waited for his absence to make money as eager whore and avaricious thief. Preacher Murrell, it was said, left her to preach the gospel, fearful that otherwise he "would be after her all the time like a boar during the rutting season." When he was at home he tried to break her of "walking as she did, hips swinging and breasts undulating, and long thighs molding themselves against her skirt with each step." When her husband was away she made theft for her son easier because the traveler he robbed was "so weary from the sport she had given him on his bed...that he probably would have slept through an earthquake." (The Devil's Backbone, p. 240)

Back to records, in 1823 Murrell was fined by the court for "riot." In 1825, he was arrested for gambling. In 1826 he was tried for horse stealing twice. On the second time he was sentenced to a year in prison. According to Virgil A. Stewart, Murrell was a ready killer and robber who disposed of bodies by filling their abdominal cavities with stones and sinking the bodies in streams. Murrell loved fine clothes. "And his recollections of high times in whorehouses from Nashville by Natchez to New Orleans capture forever the picture of those pleasure places. He had no poetic concern with "still unravished brides of quietness." Still, his statement of frolic and "high fun with old Mother Surgick's girls almost creates an eternal frieze of wanton middle-American girls in the gay and obscene positions of harlotry. (The Devil's Backbone. p 241)

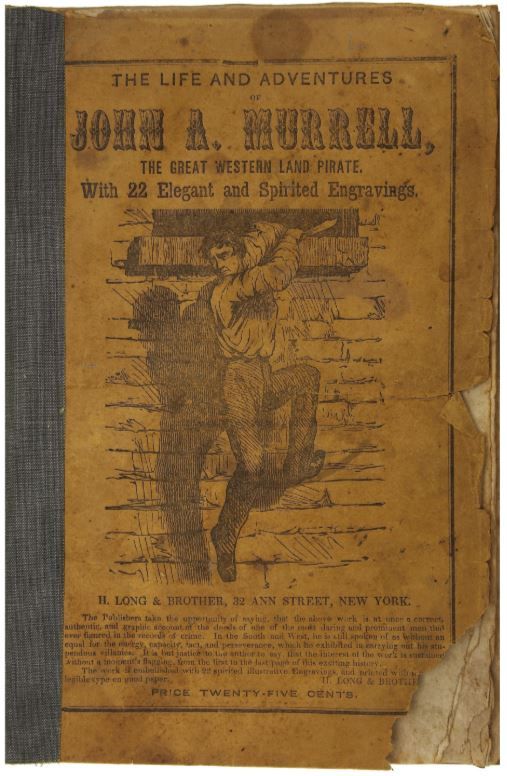

In 1845 the Police Gazette was established as a rowdy scandal sheet. Much of Virgil Stewart's book was rewritten and published by the Police Gazette, which is where the term, Great Western Land Pirate, was first applied to Murrell. All of the stories about Murrell agree that his slave stealing began in a small way. Murrell would promise a slave to lead him to freedom if the stolen Negro would let Murrell sell him once or twice on the way. After the stolen slave had been sold and stolen again so often that he might be recognizable, Murrell would kill him and dispose of the body by filling it with stones and dumping it in the river. Once he dealt with an entire slave family, mother father and children in such manner. Murrell obviously possessed some skills in organizing other rogues such as himself, building up his organization into what he called the Mystic Confederacy. He worked out deals with various 'fences' to sell his stolen loot, horses or slaves. According to Stewart, whose book was published in 1835, just before Murrell was sent to prison, Murrell planned a great slave rebellion in the southwest. Then in the panic that was sure to occur, Murrell calculated that he and his associates could loot plantations and whole towns.