Univ. of Pennsylvania, 1821-22, Medicine; Member of Mountain Creek Baptist Church; trustee of Oak Grove Academy; owned 109 slaves (Census data does say "109 slaves"); lived in Edgefield Dist., at the Coffeytown Creek plantation.

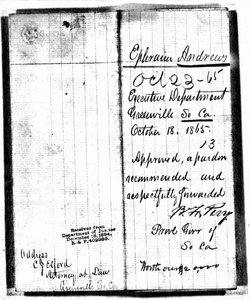

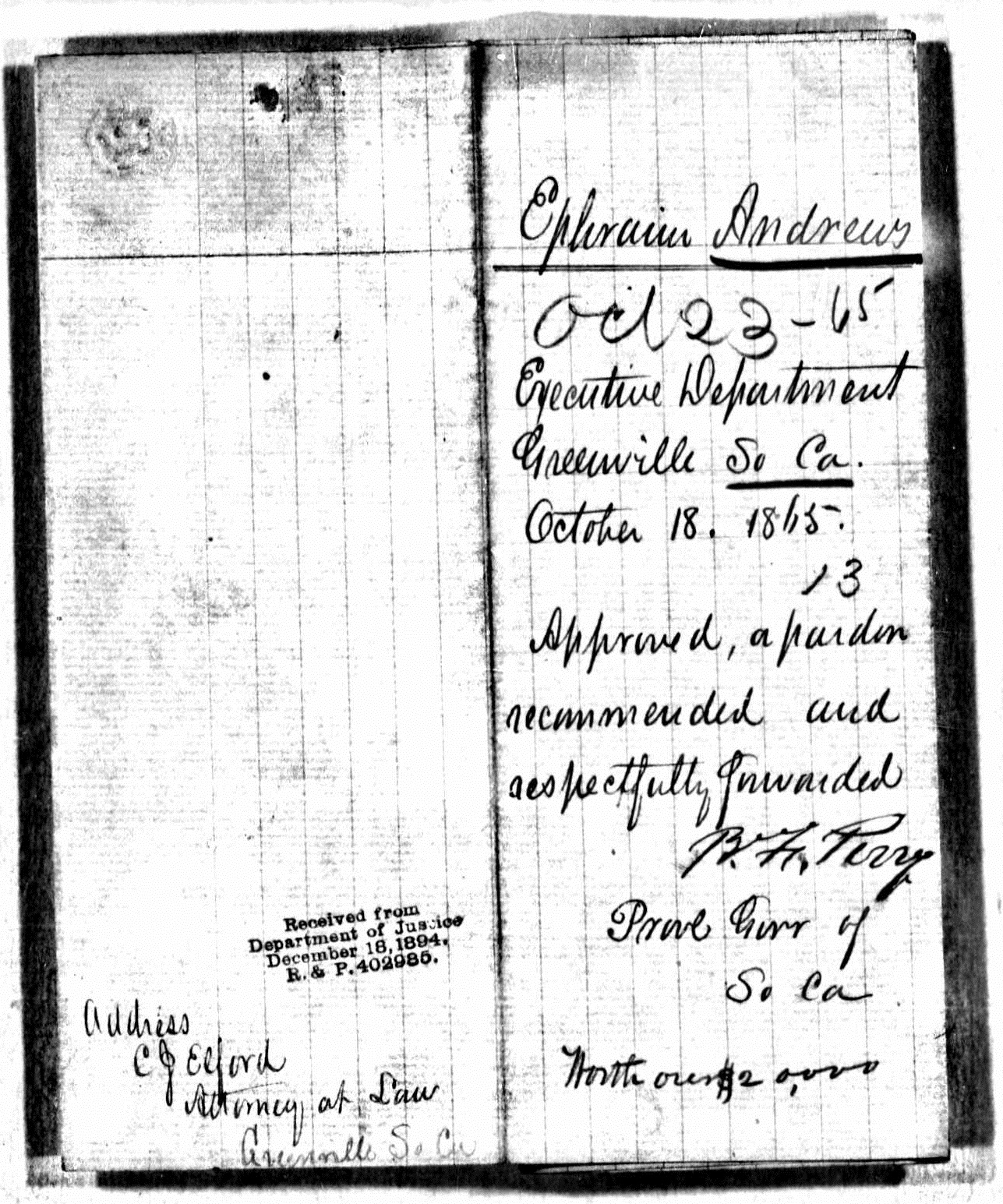

Ephraim Andrews

in the South Carolina Marriage Index, 1641-1965

Name: Ephraim Andrews

Spouse: Elizabeth France Bullock

Marriage Date: 3 May 1833

Source: Edgefield Marriage Records-Carlee McClendon-Pottersville Museum

Ephraim and Elizabeth had eight children. One died in infancy.

1. Frederick Wistar Leonard Andrews (1834-1875); married Frances J. DeVore; lived at Phoenix, S.C.; 8 children.

2. Elihue Franklin Andrews (1836 -1907); married on 25 Oct 1870 Emma Katherine Sims (1846 -1922); lived in Greenwood, S.C.; 4 children.

3. Mary Rebecca Andrews, b. 15 Sept 1839; m. first in 1856, John Leonard Griffin (5 children); married second in 1864, Rev. Robert W. Seymour (4 children).

4. Frances Emma Andrews, b. 1 Nov 1842; married on 20 Nov 1866, Judge W. Jessie Rook; lived in Greenwood, S.C.; 6 children.

5. George Worth Andrews, b. 25 Aug 1845; d. 18 Jan 1914; married on 27 Oct 1870, Amelia Ann Reeder (1849-1909); 6 children.

6. Adelaide Virginia Andrews, b. 26 Feb 1850; d. 27 Mar 1878; married on 22 Oct 1872, W. M. Wakefield; 1 child.

7. William Allen “Bose” Andrews, b. 26 Nov 1852; d. 10 Apr 1927; married first Fannie Sims; married second Margaret Wright; 3 children.

Ephraim and his brother, William, located near the original Phoenix (now Epworth) community of Greenwood County (SC) early in the 19th century. He studied medicine in Philadelphia. By 1830, he was living on Cuffytown Creek in Greenwood County. In 1833, he married and moved to lands owned by his wife along Scott's Ferry Road, SW of Kirksey, and built a large home. Both Dr. Ephraim and Frances are buried on the place. From "Greenwood County Sketches / Old Roads and Early Families" by Margaret Watson, Attic Press, Greenwood, SC 1982 (Revised)

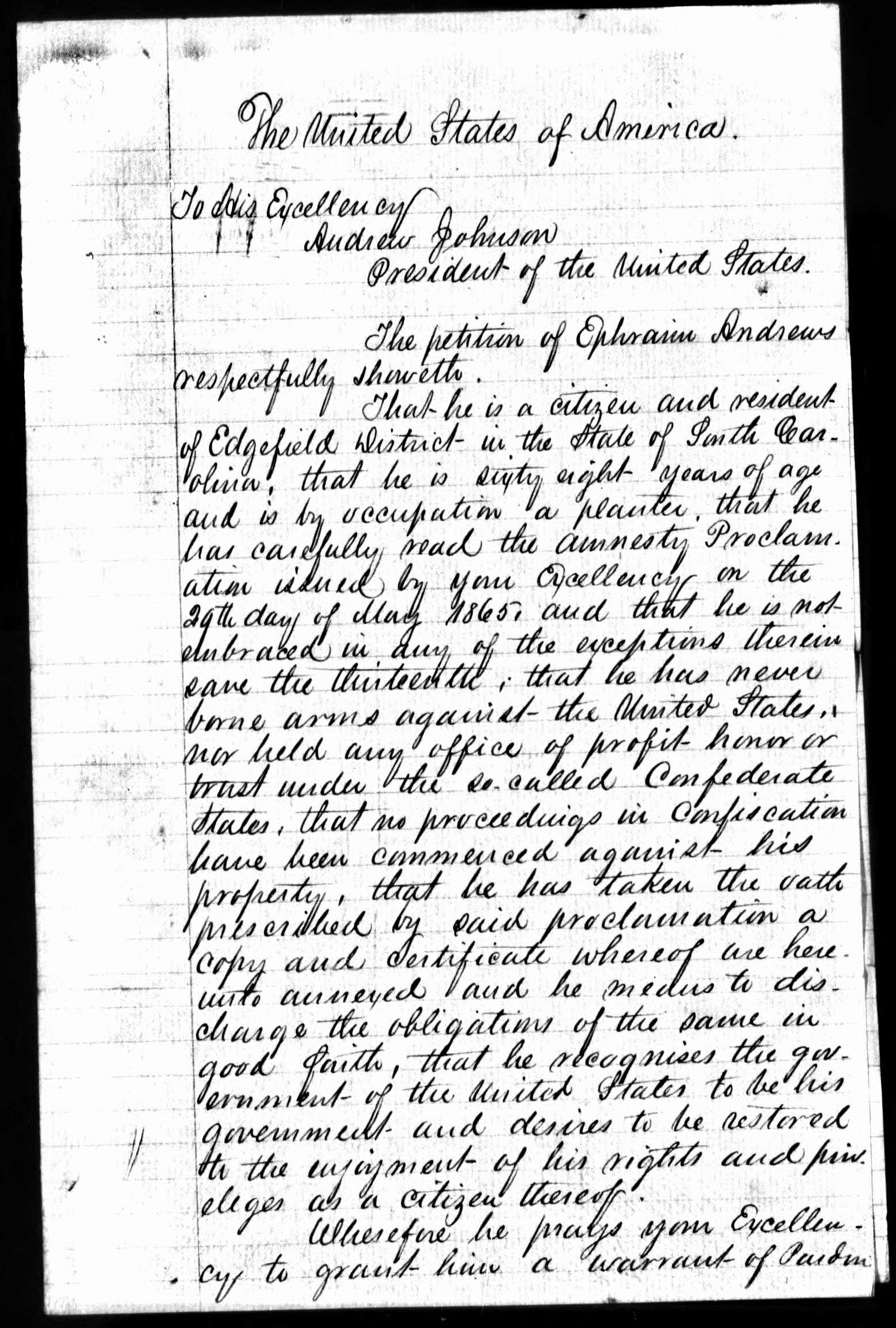

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

To his Excellency

Andrew Johnson

President of the United States

The petition of Ephraim Andrews respectfully showeth.

That he is a citizen and resident of Edgefield District in the State of South Carolina, that he is sixty eight years of age and is by occupation a planter, that he has carefully read the amnesty Proclamation issued by your excellency on the 29th day of May 1865, and that he is not embraced in any of the exceptions therein save the thirteenth, that he has never borne arms against the United States, nor held any office of profit honor or trust under the so-called Confederate States, that no proceedings in confiscation have been commenced against his property, that he has taken the oath prescribed by said proclamation a copy and certificate whereof are here unto annexed and he means to discharge the obligations of the same in good faith, that he recognizes the government of the United States to be his government and desires to be restored to the enjoyment of his rights and privileges as a citizen thereof.

Wherefore he prays your Excellency to grant him a warrant of Pardon and he will ever pray be

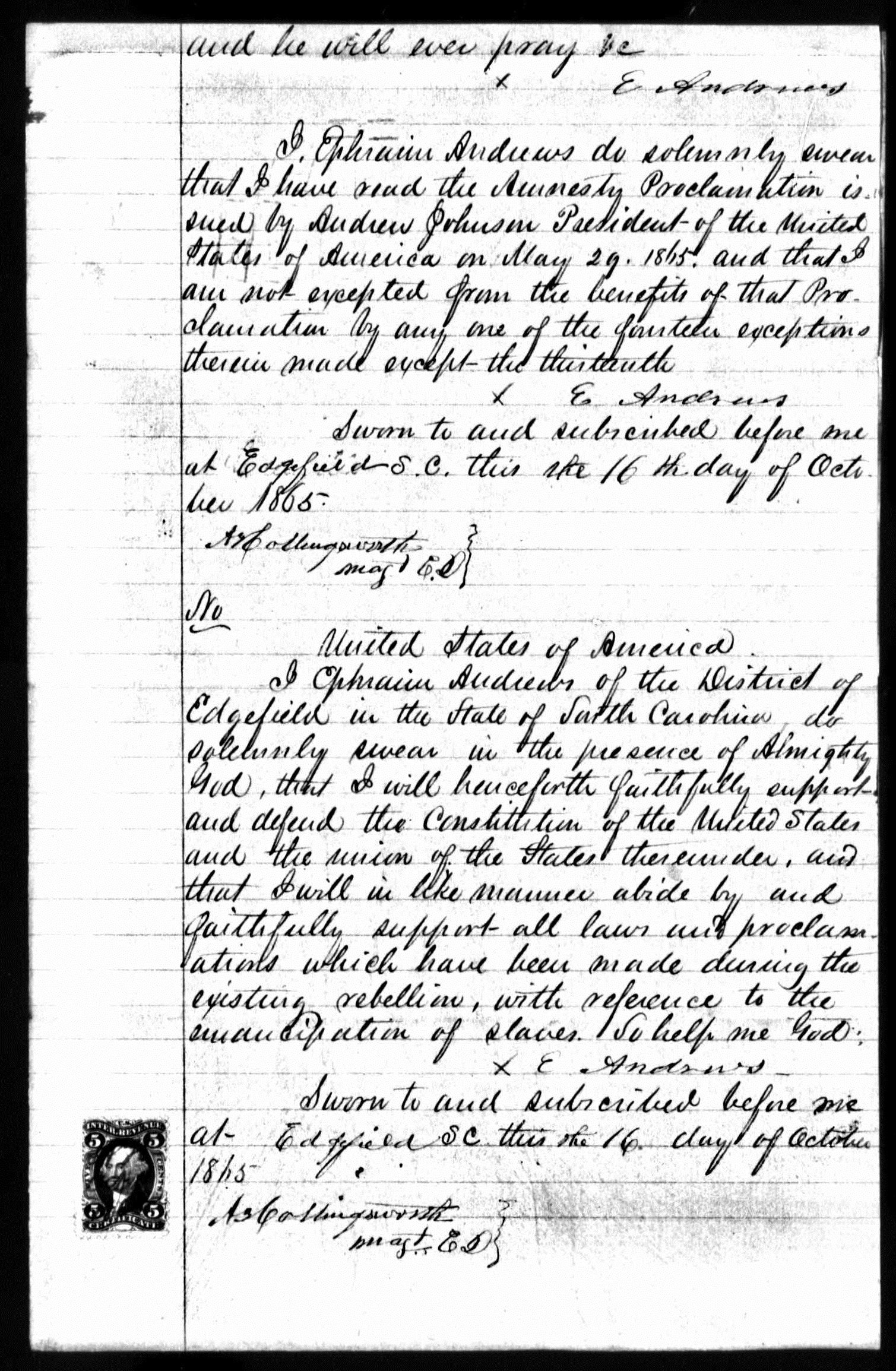

X E. Andrews

I, Ephraim Andrews do solemnly swear that I have read the Amnesty Proclamation issued by Andrew Johnson President of the United States of America on May 29, 1865, and that I am not excepted from the benefits of that Proclamation by any one of the fourteen exceptions therein made except the thirteenth,

X E. Andrews

Swarn to and subscrined before me at Edgefield S.C. this the 16th day of October, 1865.

As Collingsworth

may 1 C.D.

No

United States of America

I Ephraim Andrews of the District of Edgefield in the State of South Carolina do solemnly swear in the presence of Almighty God, that I will henceforth faithfully support and defend the Constitution of the United States and the union of the States thereunder, and that I will in like manner abide by and faithfully support all laws and proclamations which have been made during the existing rebellion, with reference to the emancipation of slaves. So Help me God.

X E. Andrews

Sworn to and subscribed before me at Edgefield SC this the 16 day of October 1865.

As Collingsworth

puagt E D

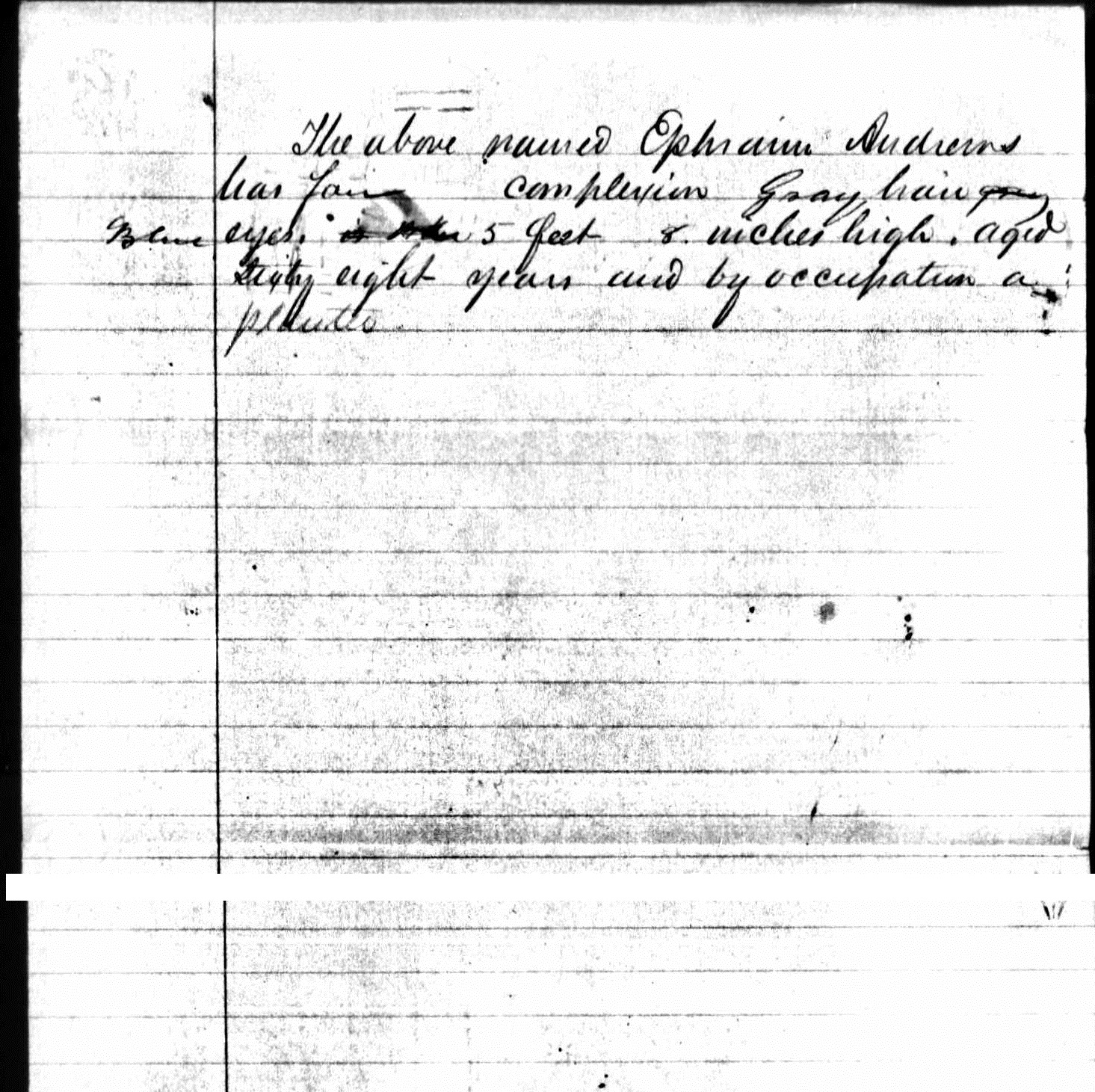

The above named Ephraim Andrews has fair complexion, gray hair, blue eyes, is about 5 feet eight inches high, aged sixty eight years and by occupation a planter.

Ephraim Andrews

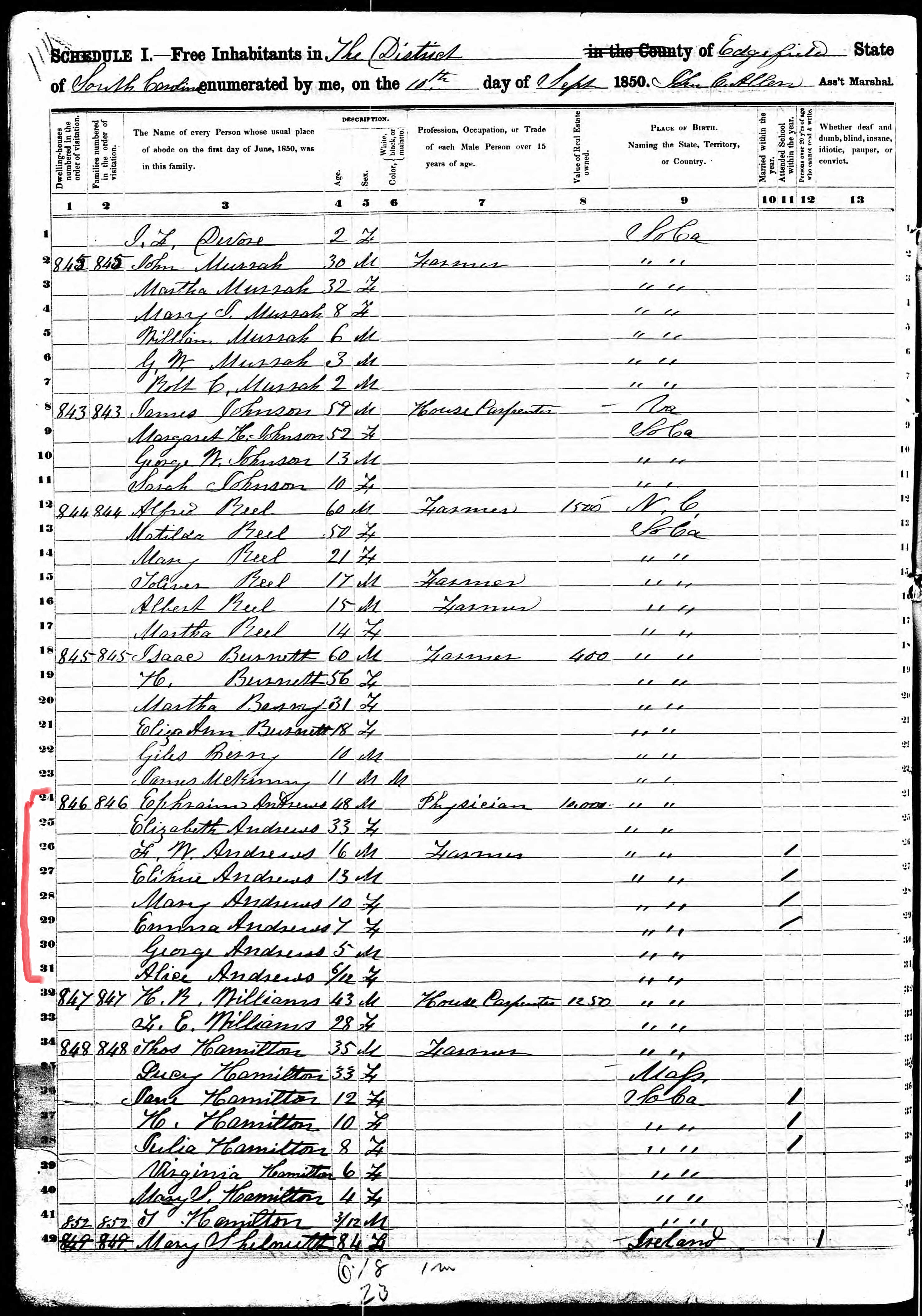

in the 1850 United States Federal Census

Name: Ephraim Andrews

Age: 48

Birth Year: abt 1802

Birthplace: South Carolina

Home in 1850: The District, Edgefield, South Carolina, USA

Gender: Male

Family Number: 846

Household Members:

Name Age

Ephraim Andrews 48 Physician

Elizabeth Andrews 33

F W Andrews 16 Farmer

Elihue Andrews 13

Mary Andrews 10

Emma Andrews 7

George Andrews 5

Alice Andrews 0

E F Andrews

in the 1860 United States Federal Census

Name: E F Andrews

Age: 44

Birth Year: abt 1816

Gender: Female

Birth Place: South Carolina

Home in 1860: Saluda Regiment, Edgefield, South Carolina

Post Office: Kirks Crossroads

Family Number: 173

Value of real estate: $25,000

Value of Personal Estate $95,565

Household Members:

Name Age

E Andrews 59 Retired Physician

E F Andrews 44

Elihue Andrews 23

M R Griffin 20

E F Andrews 17

G W Andrews 14

A V Andrews 10

W A Andrews 7

E E Griffin 2

E A Griffin 10/12

Ephraim Andrews

in the 1870 United States Federal Census

Name: Ephraim Andrews

Age in 1870: 69

Birth Year: abt 1801

Birthplace: South Carolina

Dwelling Number: 223

Home in 1870: Gray, Edgefield, South Carolina

Race: White

Gender: Male

Occupation: Farmer

Male Citizen Over 21: Y

Personal Estate Value: 480

Real Estate Value: 3000

Household Members:

Name Age

Ephraim Andrews 69

Elizabeth Andrews 54

Addie Andrews 19

William Andrews 17

It is not known whether the petitioner below, Lucy Andrews, is a former slave of Ephraim A. Andrews or of one of our cousins in South Carolina. (Some have suggested that this pre-Civil War petition was a ploy intended to convince the public that slavery benefits the enslaved.)

Slavery Petitions

South Carolina, 1858

To the Honorable, the Senate, and House of Representatives, of the Legislature, of the State of South Carolina- The humble Petition of Lucy Andrews, a free Person of color, would respectfully represent unto your Honorable Body, that she is now sixteen years of age, (and the Mother of an Infant Child) being a Descendant, of a White Woman, and her Father a Slave; That she is dissatisfied with her present condition being compelled to go about from place to place, to seek employment for her support, and not permitted to stay at any place more than a week, or two, at a time, no one caring about employing her- That she expects to raise a family, and will not be able to support them- That she sees, and knows, to her own sorrow, and regret, that Slaves are far more happy, and enjoy themselves far better, than she does, in her present isolated condition of freedom; and are well treated, and cared for by their Masters, whilst she is going about, from place to place, hunting employment for her support. That she cannot enjoy herself, situated as She now is, and therefore prefers Slavery, to freedom, in her present condition. Your Petitioner therefore prays that your Honorable Body, would enact a law authorizing and permitting her to go voluntarily, into Slavery, and select her own Master, and your Petitioner will, as in duty bound, ever pray &c- her Lucy X Andrews mark

Source: Records of the General Assembly, Lucy Andrews to the Senate and House of Representatives of South Carolina, 1858, ND #2811, SCDAH. Referred to Committee on Colored Population. No act was passed. PAR #11385806.

Causes of the Civil War – Speaking to the Dead Bill Andrews

[William Xavier Andrews, Columbia, Tennessee, May 28, 2010]

As a reenactor, I’m frequently asked to speak on the subject of the Civil War at historical associations, civic clubs and schools. I’m particularly fond of the schools because the invitations usually come from former students-turned-teachers and because my audience, whether fifth-graders or seniors, is always enthusiastic. Sometimes I bring my horse where, spurring the mount to a full gallop, I split watermelons with a saber. On one of these outings, the teacher, before turning the program over to me, announced “and, as we all know, slavery was not the cause of the Civil War.” I was caught off guard because she had been one of my students and she never would have gotten the idea from me.

Interestingly, I recently came across a term paper written by my father when he was an undergraduate student at Vanderbilt in the mid 1930’s. In it he made the same point. His paper agreed with many of the tenets of the Lost Cause, a literary and intellectual movement romanticizing the antebellum South and repudiating the slave-centered notion of the cause for secession. Dad was a product of his time and place, an impressionable youth expressing views that might earn him an A. Vanderbilt at the time was still basking in the brilliant glow of the Southern Agrarians or Fugitive writers whose views reflected Lost Cause sentiments.

I’m a direct descendant of Thomas Andrews [Dr. Ephraim Andrews' great-great grandfather] who arrived in Virginia in 1685 and became a slaveholding planter. One of his descendants was Dr. Ephram Andrews who owned a hundred and nine slaves. Another, William O. Andrews, was a slave owner who fought for the Confederacy. The revisionist notion that slavery was an insignificant factor in secession would have come as a surprise to Ephram and William. They were willing to fight for their constitutional right to own other people.

In any case, if one wishes to refute the assertion that slavery was the fundamental cause of the Civil War, one should stick to secondary sources, particularly those written by early 20th century historians. The problem with original sources, particularly official documents, is that they punch gaping holes in the revisionist contention that slavery played merely an ancillary role in the secession crisis. Consulting original sources on this matter is like communicating with the dead. The authors of these documents speak to us from the most consequential time in our history. Their words carry weight because they were expressed by those who influenced the cause, course and outcome of the Civil War.

Between December 1860 and August of 1861, special conventions were called in the southern states to decide on the momentous question of secession. In these, the planter elites dominated the proceedings and drew up the secession documents – both the formal ordinances and the official explanations to justify separation. Protection of the institution of slavery was unambiguously a common thread in all.

South Carolina, referencing the non-slaveholding states in the North in its secession document, declared “They have encouraged and assisted thousands of our slaves to leave their homes … and have united in the election of a man to the high office of President of the United States whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery…”

In the attempt to bring additional states into the Confederacy, apologists for slavery in South Carolina declared that “there can be but one end by the submission by the South to the rule of a sectional anti-slavery government at Washington; and that end, directly or indirectly, must be the emancipation of the slaves of the South.”

The Mississippi delegation wrote in its formal secession document “Our position is thoroughly indentified with the institution of slavery – the greatest material interest of the world… A blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization…There was no choice left us but submission to the mandates of abolition or a dissolution of the Union… We must either submit to degradation and to the loss of property worth four billions of money, or we must secede from the Union.”

When Florida became the third state to secede, its preliminary resolution enumerated the reasons for its departure. Paramount was the election of Lincoln. The document reads: “All hope of preserving the Union on terms consistent with the safety and honor of the Slaveholding States has been finally dissipated by the recent indications of the strength of the anti-slavery sentiment in the Free States.”

Georgia likewise justified its action on the Republican victory. “The prohibition of slavery in the territories, hostility to it everywhere, the equality of the black and white races, disregard of all constitutional guarantees in its favor, were boldly proclaimed by its leaders and applauded by its followers… Why was the Republican election victory cause for secession? Because the Republican Party had been formed in May of 1854 on the almost singular issue of opposition to slavery.”

The above examples are typical of the secession documents of states leaving the Union in response to Lincoln’s election Moreover, if one examines the Confederate Constitution itself, there can be no mistaking the central role that slavery played in its formulation. There is more than a little irony in that those revisionists who say that States’ Rights was the central issue bringing on secession tend to overlook the fact that this new constitution denied its member states the right to secede or to end slavery within their borders.

I know that much of this flies in the face of what many of us have been told or taught by authority figures and I can appreciate how a coming to terms with it can be discomforting. I would suggest that you read the secession documents and the Confederate Constitution in their entirety for the purpose of contextual insight. It would also be of benefit to reflect on the eloquent words of the Great Emancipator in his Second Inaugural Address. Just weeks before the Lee’s surrender and his own assassination, Lincoln laid the tragedy of civil war squarely at the feet of slavery.

“One eighth of the whole population were colored slaves… These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. And all knew that this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would end the Union even by war, while the Government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it…Yet, if God wills that [the war] continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as it was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”

VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY HISTORY PAPER BY William Lafayette Andrews, Jr., MARCH 8, 1939

"PROPAGANDA AND PRESS OPINION ON SLAVERY"

Propaganda has played an important role in inciting the animosity of factions of opposing forces in all wars. It played just as important a part in arousing tempers in the South and North prior to and during the Civil War. This temper in the North was due directly to the propaganda ex-pounded by writers and publishers concerning slavery and social conditions effected therefrom in the South. The temper in the South was due largely to resentment of this propaganda.

The attack on slavery became a war on a section and its way of life. "Slavery was imagined, not investigated. Southern people and Southern life were distorted into forms best suited to purposes of propaganda. Church, political party, and State were drawn in as agents of a crusade declared to be launched in the name of morality and democracy."*

The machinery of attack ranged from local and national organizations, publications of every kind from newspapers to 'best sellers', to traveling preachers and missionary bands and organized legislative lobbies. It appealed mostly to the emotions. It made abolition and morality the same thing and it impressed two ideas on the northern mind, namely, that the Southerner was "an aristocrat, an enemy of democracy in society and government, and that slave-holders were men of violent and uncontrolled passions--intemperate, licentious, and brutal." * These northern organizations taught that the South was divided into two classes, slave-holders and poor whites. The slave-holders were said to completely control the section and had as their purpose the rule or ruin of the nation.

In one pamphlet circulated in the North, the writer spoke of the "savage ferocity" of Southern men. He says that their savage nature is the result of their habit of plundering and oppressing the slave. He tells of "perpetual idleness broken only by brutal cock-fights, gander-pullings, and horse races so barbarous in character that 'the blood of the tortured animal drips from the lash and flies at every leap from the stroke of the rowel.' "

Another article declared that thousands of slave women are given up as prey to the lusts of their masters. One writer stated that the South was full of mulattoes; that its best blood flowed in the veins of its slaves.

The final conclusion was stated by Theodore Parker in 1851 when he wrote: "The South, in the main, had a. very different origin from the North. I think few if any persons settled there for religious reasons, or for the sake of the freedom of the State. It was not a moral idea which sent men to Virginia, Georgia, or Carolina. 'Men do not gather grapes of thorns.' The difference in the seed will appear in difference of the crop. In the character of the people of the North and South, it appears at this day….. Here, now, is the great cause of the difference in the material results, represented in towns and villages, by farms and factories, ships and shops; here lies the cause of the differences in the schools and colleges, churches, and in the literature; the cause of difference in men themselves. The South with its despotic idea, dishonors labor, but wishes to compromise between its idleness and its appetite, and so kidnaps men to do the work."

On a July day in 1861 the New York Herald carried the story of Southern atrocities committed on the battle field at Bull Run. It told of a private in the First Connecticut regiment who found a wounded rebel lying in the sun crying for water. He lifted the rebel and carried him to the shade where he gently laid him and gave him water from his canteen. Revived by the water the rebel drew his pistol and shot his benefactor through the heart.

Another instance was related of a troop of rebel cavalry deliberately firing upon a number of wounded men who had been placed together in the shade. "All of which," the article added, "was attributed to the barbarism of slavery, in which, and to which the Southern soldiers have been educated."

For years the Southern men and women lived under such attacks. The answer of the South to such propaganda grew from a "half apologetic defense of slavery to an aggressive assertion of a superiority of all things Southern." Slavery benefited the Negro, it was asserted, and had made twice as many Christians out of heathens as all missionary efforts put together. A Southern minister declared that he was certain that God had confined slavery to the South because its people were better fitted to lift ignorant Africans to civilization. The South declared that the slave was better off than the white factory workers of England or New England; that he was useless to himself and to society without supervision and direction, and that nature or the curse of God on Ham had destined him to servitude. It was said by the South that true republican government was possible only where all white citizens were free from drudgery; that without slavery, farmers were destined to peasantry; that slave societies alone escape the ills of labor and race wars, unemployment and old age insecurity. The South had achieved a superior civilization.

The men who organized the attack on slavery and those who developed its defense were in most cases too extreme and radical to represent true sentiment of the masses. Conservatives in both the North and the South usually dismissed them as fanatics and assured themselves that they did not represent the true feelings of the people in either section. Nevertheless as the sentiment and tension grew and politicians became more and more vehement, these conservatives became fewer.

The true relationship of master and slave was predominately different from the pictures presented by propaganda machines. There were good masters and bad masters; extremely kind ones and occasionally cruel ones, though the really cruel or hard master was a marked exception. The conduct of the slaves in the war confirm this. It was not true as sometimes claimed, that every slave was loyal to his master, but the fact that the white master could go into the army, leaving his often lonely and remote farm or plantation, his wife and children, and frequently even money and jewels, in the care of the slave for whose liberty his opponent was fighting, indicates at least that there could have been no widespread hatred of the masters or resentment against them. Usually the relationship between slave and master was a personal one and there was none of that impersonalism which made for the discontent and brutality suffered by the New England factory worker. But if the plantation was of unusual size or if the master owned several of them in different places, this personal relationship might be lost, and the slaves' lives could be made a hell on earth. However, even when a slave was placed in good surroundings there was always the danger of his being sold. The best families prided themselves on not selling their slaves and on not breaking up slave families, but even the best of such owners might fall into circumstances necessitating the sale of the slaves. It is interesting to survey some of the leading articles that appeared in the various newspapers of the country prior to and during the rebellion. It is difficult to determine just how many of these articles are propaganda and how many represent the true feelings of the editors and writers. No doubt the fault was not much in the newspapers themselves but rather in the sources of their information. An interesting article concerning the famous assault by Preston S. Brooke, a member of the House of Representatives from South Carolina, upon Senator Sumner of Massachusetts, appeared in the New York Evening Post, May 23, 1856. The article entitled, "The Outrage On Mr. Sumner" is directed against the Southern Representative and Senator Butler. An excerpt follows: "The friends of slavery at Washington are attempting to silence the members of Congress from the free states by the same modes of discipline which make the slaves units on their plantations. Two ruffians from South Carolina, yesterday made the Senate Chamber the scene of their cowardly brutality. They had armed themselves with heavy canes, and-approaching Mr.Sumner, who was seated in his chair writing, Brooks struck him with his cane a violent blow on the head, which brought him stunned to the floor, and Keith with his weapon kept off the by-standers, while the other Ruffian, Brooks, repeated the blows upon the head of the apparently lifeless victim until his cane was shattered to fragments. Mr. Sumner was conveyed from the Senate Chamber bleeding and senseless, so severely wounded that the physician attending did not think it prudent to allow friends to have access to him. The excuse for this base assault is that Mr. Sumner had in the course of debate spoken disrespectfully of Mr. Butler, a relative of Preston S. Brooks, one of the authors of the outrage. No possible indecorum of language on the part of Mr. Sumner could excuse, much less justify an attack like this; but we have carefully examined his speech to see if it contains any matter which could even extenuate such an act of violence, and we find none. He had ridiculed Mr. Butler's devotion to slavery, it is true, but the weapons of ridicule and contempt in debate is by common consent as fair and allowable weapons as argument. We agree fully with Mr. Sumner that Mr. Butler is a monomaniac in the respect of which we speak; we certainly should place no confidence in any representation he might make which concerned the subject of slavery…… The truth is, that the proslavery party, which rules the Senate, looks upon violence as the proper instrument of its designs. Violence reigns in the streets of Washington; violence has now found its way to the Senate Chamber; In short violence is the order of the day; the North is to be pushed to the wall by it, and this plot will succeed if the people of the free States are as apathetic as the slaveholders are insolent."** It can readily be seen that the author of this article is vehemently opposed to the pro-slavery party, and the article illustrates perfectly the use of the newspaper for political means. An article appeared in the Springfield Republican October 19, 1859, praising the character of John Brown. "The universal feeling is that John Brown is a hero--a misguided and insane man, but nevertheless inspired with a genuine heroism. He has a large infusion of the stern old Puritan element in him." The text of the article appearing in the Springfield Republican December 3, 1859, the day after the execution of John Brown, follows! "John Brown still lives. The great State of Virginia has hung his venerable body upon the ignominous gallows, and released John Brown himself to join the noble army of martyrs.............................. A Christian man hung by Christians for acting upon his convictions of duty--a brave man hung for his chivalrous and self-sacrificing deed of humanity--a philanthropist hung for seeking the liberty of oppressed men. No outcry about violated law can cover up the essential enormity of a deed like this." Editorials such as those above did much to influence the populations of both the North and the South. By appealing to the emotions, sense of morality, and by publishing doubtful stories of atrocities the newspapers, along with the teachings of preachers and political speakers, were able to whip the fighting spirit of people on either side to a feverish pitch. This method of influencing the public opinion of all factions has been employed in. all of the wars since the Civil War and is playing its same role in totalitarian and democratic countries alike.

_____

*Slavery and the Civil War, Southern Review, Autumn, 1938

**This article is thought to be the work of William Cullen Bryant, the editor of the paper at that time.

Friday, December 22, 2006 12:49 AM

From: WL Andrews' Son William Xavier Andrews

I did not have a copy of this paper. Its theme reflects the common view of historians both North and South after the Civil War, a romanticized view of the agricultural South as portrayed in the literature of such Vanderbilt Agrarian writers as Penn Warren and Tate.

If Daddy had been at Vanderbilt thirty years later, the literature would have been much harsher on the South. For those people who claim that slavery was not the major cause of the Civil War, I came across an interesting document when I was at Corinth, Mississippi last year. It was at the Civil War museum there and it was an original copy of Mississippi's declaration of secession in 1861.

Univ. of Pennsylvania, 1821-22, Medicine; Member of Mountain Creek Baptist Church; trustee of Oak Grove Academy; owned 109 slaves (Census data does say "109 slaves"); lived in Edgefield Dist., at the Coffeytown Creek plantation.

Ephraim Andrews

in the South Carolina Marriage Index, 1641-1965

Name: Ephraim Andrews

Spouse: Elizabeth France Bullock

Marriage Date: 3 May 1833

Source: Edgefield Marriage Records-Carlee McClendon-Pottersville Museum

Ephraim and Elizabeth had eight children. One died in infancy.

1. Frederick Wistar Leonard Andrews (1834-1875); married Frances J. DeVore; lived at Phoenix, S.C.; 8 children.

2. Elihue Franklin Andrews (1836 -1907); married on 25 Oct 1870 Emma Katherine Sims (1846 -1922); lived in Greenwood, S.C.; 4 children.

3. Mary Rebecca Andrews, b. 15 Sept 1839; m. first in 1856, John Leonard Griffin (5 children); married second in 1864, Rev. Robert W. Seymour (4 children).

4. Frances Emma Andrews, b. 1 Nov 1842; married on 20 Nov 1866, Judge W. Jessie Rook; lived in Greenwood, S.C.; 6 children.

5. George Worth Andrews, b. 25 Aug 1845; d. 18 Jan 1914; married on 27 Oct 1870, Amelia Ann Reeder (1849-1909); 6 children.

6. Adelaide Virginia Andrews, b. 26 Feb 1850; d. 27 Mar 1878; married on 22 Oct 1872, W. M. Wakefield; 1 child.

7. William Allen “Bose” Andrews, b. 26 Nov 1852; d. 10 Apr 1927; married first Fannie Sims; married second Margaret Wright; 3 children.

Ephraim and his brother, William, located near the original Phoenix (now Epworth) community of Greenwood County (SC) early in the 19th century. He studied medicine in Philadelphia. By 1830, he was living on Cuffytown Creek in Greenwood County. In 1833, he married and moved to lands owned by his wife along Scott's Ferry Road, SW of Kirksey, and built a large home. Both Dr. Ephraim and Frances are buried on the place. From "Greenwood County Sketches / Old Roads and Early Families" by Margaret Watson, Attic Press, Greenwood, SC 1982 (Revised)

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

To his Excellency

Andrew Johnson

President of the United States

The petition of Ephraim Andrews respectfully showeth.

That he is a citizen and resident of Edgefield District in the State of South Carolina, that he is sixty eight years of age and is by occupation a planter, that he has carefully read the amnesty Proclamation issued by your excellency on the 29th day of May 1865, and that he is not embraced in any of the exceptions therein save the thirteenth, that he has never borne arms against the United States, nor held any office of profit honor or trust under the so-called Confederate States, that no proceedings in confiscation have been commenced against his property, that he has taken the oath prescribed by said proclamation a copy and certificate whereof are here unto annexed and he means to discharge the obligations of the same in good faith, that he recognizes the government of the United States to be his government and desires to be restored to the enjoyment of his rights and privileges as a citizen thereof.

Wherefore he prays your Excellency to grant him a warrant of Pardon and he will ever pray be

X E. Andrews

I, Ephraim Andrews do solemnly swear that I have read the Amnesty Proclamation issued by Andrew Johnson President of the United States of America on May 29, 1865, and that I am not excepted from the benefits of that Proclamation by any one of the fourteen exceptions therein made except the thirteenth,

X E. Andrews

Swarn to and subscrined before me at Edgefield S.C. this the 16th day of October, 1865.

As Collingsworth

may 1 C.D.

No

United States of America

I Ephraim Andrews of the District of Edgefield in the State of South Carolina do solemnly swear in the presence of Almighty God, that I will henceforth faithfully support and defend the Constitution of the United States and the union of the States thereunder, and that I will in like manner abide by and faithfully support all laws and proclamations which have been made during the existing rebellion, with reference to the emancipation of slaves. So Help me God.

X E. Andrews

Sworn to and subscribed before me at Edgefield SC this the 16 day of October 1865.

As Collingsworth

puagt E D

The above named Ephraim Andrews has fair complexion, gray hair, blue eyes, is about 5 feet eight inches high, aged sixty eight years and by occupation a planter.

Ephraim Andrews

in the 1850 United States Federal Census

Name: Ephraim Andrews

Age: 48

Birth Year: abt 1802

Birthplace: South Carolina

Home in 1850: The District, Edgefield, South Carolina, USA

Gender: Male

Family Number: 846

Household Members:

Name Age

Ephraim Andrews 48 Physician

Elizabeth Andrews 33

F W Andrews 16 Farmer

Elihue Andrews 13

Mary Andrews 10

Emma Andrews 7

George Andrews 5

Alice Andrews 0

E F Andrews

in the 1860 United States Federal Census

Name: E F Andrews

Age: 44

Birth Year: abt 1816

Gender: Female

Birth Place: South Carolina

Home in 1860: Saluda Regiment, Edgefield, South Carolina

Post Office: Kirks Crossroads

Family Number: 173

Value of real estate: $25,000

Value of Personal Estate $95,565

Household Members:

Name Age

E Andrews 59 Retired Physician

E F Andrews 44

Elihue Andrews 23

M R Griffin 20

E F Andrews 17

G W Andrews 14

A V Andrews 10

W A Andrews 7

E E Griffin 2

E A Griffin 10/12

Ephraim Andrews

in the 1870 United States Federal Census

Name: Ephraim Andrews

Age in 1870: 69

Birth Year: abt 1801

Birthplace: South Carolina

Dwelling Number: 223

Home in 1870: Gray, Edgefield, South Carolina

Race: White

Gender: Male

Occupation: Farmer

Male Citizen Over 21: Y

Personal Estate Value: 480

Real Estate Value: 3000

Household Members:

Name Age

Ephraim Andrews 69

Elizabeth Andrews 54

Addie Andrews 19

William Andrews 17

It is not known whether the petitioner below, Lucy Andrews, is a former slave of Ephraim A. Andrews or of one of our cousins in South Carolina. (Some have suggested that this pre-Civil War petition was a ploy intended to convince the public that slavery benefits the enslaved.)

Slavery Petitions

South Carolina, 1858

To the Honorable, the Senate, and House of Representatives, of the Legislature, of the State of South Carolina- The humble Petition of Lucy Andrews, a free Person of color, would respectfully represent unto your Honorable Body, that she is now sixteen years of age, (and the Mother of an Infant Child) being a Descendant, of a White Woman, and her Father a Slave; That she is dissatisfied with her present condition being compelled to go about from place to place, to seek employment for her support, and not permitted to stay at any place more than a week, or two, at a time, no one caring about employing her- That she expects to raise a family, and will not be able to support them- That she sees, and knows, to her own sorrow, and regret, that Slaves are far more happy, and enjoy themselves far better, than she does, in her present isolated condition of freedom; and are well treated, and cared for by their Masters, whilst she is going about, from place to place, hunting employment for her support. That she cannot enjoy herself, situated as She now is, and therefore prefers Slavery, to freedom, in her present condition. Your Petitioner therefore prays that your Honorable Body, would enact a law authorizing and permitting her to go voluntarily, into Slavery, and select her own Master, and your Petitioner will, as in duty bound, ever pray &c- her Lucy X Andrews mark

Source: Records of the General Assembly, Lucy Andrews to the Senate and House of Representatives of South Carolina, 1858, ND #2811, SCDAH. Referred to Committee on Colored Population. No act was passed. PAR #11385806.

Causes of the Civil War – Speaking to the Dead Bill Andrews

[William Xavier Andrews, Columbia, Tennessee, May 28, 2010]

As a reenactor, I’m frequently asked to speak on the subject of the Civil War at historical associations, civic clubs and schools. I’m particularly fond of the schools because the invitations usually come from former students-turned-teachers and because my audience, whether fifth-graders or seniors, is always enthusiastic. Sometimes I bring my horse where, spurring the mount to a full gallop, I split watermelons with a saber. On one of these outings, the teacher, before turning the program over to me, announced “and, as we all know, slavery was not the cause of the Civil War.” I was caught off guard because she had been one of my students and she never would have gotten the idea from me.

Interestingly, I recently came across a term paper written by my father when he was an undergraduate student at Vanderbilt in the mid 1930’s. In it he made the same point. His paper agreed with many of the tenets of the Lost Cause, a literary and intellectual movement romanticizing the antebellum South and repudiating the slave-centered notion of the cause for secession. Dad was a product of his time and place, an impressionable youth expressing views that might earn him an A. Vanderbilt at the time was still basking in the brilliant glow of the Southern Agrarians or Fugitive writers whose views reflected Lost Cause sentiments.

I’m a direct descendant of Thomas Andrews [Dr. Ephraim Andrews' great-great grandfather] who arrived in Virginia in 1685 and became a slaveholding planter. One of his descendants was Dr. Ephram Andrews who owned a hundred and nine slaves. Another, William O. Andrews, was a slave owner who fought for the Confederacy. The revisionist notion that slavery was an insignificant factor in secession would have come as a surprise to Ephram and William. They were willing to fight for their constitutional right to own other people.

In any case, if one wishes to refute the assertion that slavery was the fundamental cause of the Civil War, one should stick to secondary sources, particularly those written by early 20th century historians. The problem with original sources, particularly official documents, is that they punch gaping holes in the revisionist contention that slavery played merely an ancillary role in the secession crisis. Consulting original sources on this matter is like communicating with the dead. The authors of these documents speak to us from the most consequential time in our history. Their words carry weight because they were expressed by those who influenced the cause, course and outcome of the Civil War.

Between December 1860 and August of 1861, special conventions were called in the southern states to decide on the momentous question of secession. In these, the planter elites dominated the proceedings and drew up the secession documents – both the formal ordinances and the official explanations to justify separation. Protection of the institution of slavery was unambiguously a common thread in all.

South Carolina, referencing the non-slaveholding states in the North in its secession document, declared “They have encouraged and assisted thousands of our slaves to leave their homes … and have united in the election of a man to the high office of President of the United States whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery…”

In the attempt to bring additional states into the Confederacy, apologists for slavery in South Carolina declared that “there can be but one end by the submission by the South to the rule of a sectional anti-slavery government at Washington; and that end, directly or indirectly, must be the emancipation of the slaves of the South.”

The Mississippi delegation wrote in its formal secession document “Our position is thoroughly indentified with the institution of slavery – the greatest material interest of the world… A blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization…There was no choice left us but submission to the mandates of abolition or a dissolution of the Union… We must either submit to degradation and to the loss of property worth four billions of money, or we must secede from the Union.”

When Florida became the third state to secede, its preliminary resolution enumerated the reasons for its departure. Paramount was the election of Lincoln. The document reads: “All hope of preserving the Union on terms consistent with the safety and honor of the Slaveholding States has been finally dissipated by the recent indications of the strength of the anti-slavery sentiment in the Free States.”

Georgia likewise justified its action on the Republican victory. “The prohibition of slavery in the territories, hostility to it everywhere, the equality of the black and white races, disregard of all constitutional guarantees in its favor, were boldly proclaimed by its leaders and applauded by its followers… Why was the Republican election victory cause for secession? Because the Republican Party had been formed in May of 1854 on the almost singular issue of opposition to slavery.”

The above examples are typical of the secession documents of states leaving the Union in response to Lincoln’s election Moreover, if one examines the Confederate Constitution itself, there can be no mistaking the central role that slavery played in its formulation. There is more than a little irony in that those revisionists who say that States’ Rights was the central issue bringing on secession tend to overlook the fact that this new constitution denied its member states the right to secede or to end slavery within their borders.

I know that much of this flies in the face of what many of us have been told or taught by authority figures and I can appreciate how a coming to terms with it can be discomforting. I would suggest that you read the secession documents and the Confederate Constitution in their entirety for the purpose of contextual insight. It would also be of benefit to reflect on the eloquent words of the Great Emancipator in his Second Inaugural Address. Just weeks before the Lee’s surrender and his own assassination, Lincoln laid the tragedy of civil war squarely at the feet of slavery.

“One eighth of the whole population were colored slaves… These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. And all knew that this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would end the Union even by war, while the Government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it…Yet, if God wills that [the war] continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as it was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”

VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY HISTORY PAPER BY William Lafayette Andrews, Jr., MARCH 8, 1939

"PROPAGANDA AND PRESS OPINION ON SLAVERY"

Propaganda has played an important role in inciting the animosity of factions of opposing forces in all wars. It played just as important a part in arousing tempers in the South and North prior to and during the Civil War. This temper in the North was due directly to the propaganda ex-pounded by writers and publishers concerning slavery and social conditions effected therefrom in the South. The temper in the South was due largely to resentment of this propaganda.

The attack on slavery became a war on a section and its way of life. "Slavery was imagined, not investigated. Southern people and Southern life were distorted into forms best suited to purposes of propaganda. Church, political party, and State were drawn in as agents of a crusade declared to be launched in the name of morality and democracy."*

The machinery of attack ranged from local and national organizations, publications of every kind from newspapers to 'best sellers', to traveling preachers and missionary bands and organized legislative lobbies. It appealed mostly to the emotions. It made abolition and morality the same thing and it impressed two ideas on the northern mind, namely, that the Southerner was "an aristocrat, an enemy of democracy in society and government, and that slave-holders were men of violent and uncontrolled passions--intemperate, licentious, and brutal." * These northern organizations taught that the South was divided into two classes, slave-holders and poor whites. The slave-holders were said to completely control the section and had as their purpose the rule or ruin of the nation.

In one pamphlet circulated in the North, the writer spoke of the "savage ferocity" of Southern men. He says that their savage nature is the result of their habit of plundering and oppressing the slave. He tells of "perpetual idleness broken only by brutal cock-fights, gander-pullings, and horse races so barbarous in character that 'the blood of the tortured animal drips from the lash and flies at every leap from the stroke of the rowel.' "

Another article declared that thousands of slave women are given up as prey to the lusts of their masters. One writer stated that the South was full of mulattoes; that its best blood flowed in the veins of its slaves.

The final conclusion was stated by Theodore Parker in 1851 when he wrote: "The South, in the main, had a. very different origin from the North. I think few if any persons settled there for religious reasons, or for the sake of the freedom of the State. It was not a moral idea which sent men to Virginia, Georgia, or Carolina. 'Men do not gather grapes of thorns.' The difference in the seed will appear in difference of the crop. In the character of the people of the North and South, it appears at this day….. Here, now, is the great cause of the difference in the material results, represented in towns and villages, by farms and factories, ships and shops; here lies the cause of the differences in the schools and colleges, churches, and in the literature; the cause of difference in men themselves. The South with its despotic idea, dishonors labor, but wishes to compromise between its idleness and its appetite, and so kidnaps men to do the work."

On a July day in 1861 the New York Herald carried the story of Southern atrocities committed on the battle field at Bull Run. It told of a private in the First Connecticut regiment who found a wounded rebel lying in the sun crying for water. He lifted the rebel and carried him to the shade where he gently laid him and gave him water from his canteen. Revived by the water the rebel drew his pistol and shot his benefactor through the heart.

Another instance was related of a troop of rebel cavalry deliberately firing upon a number of wounded men who had been placed together in the shade. "All of which," the article added, "was attributed to the barbarism of slavery, in which, and to which the Southern soldiers have been educated."

For years the Southern men and women lived under such attacks. The answer of the South to such propaganda grew from a "half apologetic defense of slavery to an aggressive assertion of a superiority of all things Southern." Slavery benefited the Negro, it was asserted, and had made twice as many Christians out of heathens as all missionary efforts put together. A Southern minister declared that he was certain that God had confined slavery to the South because its people were better fitted to lift ignorant Africans to civilization. The South declared that the slave was better off than the white factory workers of England or New England; that he was useless to himself and to society without supervision and direction, and that nature or the curse of God on Ham had destined him to servitude. It was said by the South that true republican government was possible only where all white citizens were free from drudgery; that without slavery, farmers were destined to peasantry; that slave societies alone escape the ills of labor and race wars, unemployment and old age insecurity. The South had achieved a superior civilization.

The men who organized the attack on slavery and those who developed its defense were in most cases too extreme and radical to represent true sentiment of the masses. Conservatives in both the North and the South usually dismissed them as fanatics and assured themselves that they did not represent the true feelings of the people in either section. Nevertheless as the sentiment and tension grew and politicians became more and more vehement, these conservatives became fewer.

The true relationship of master and slave was predominately different from the pictures presented by propaganda machines. There were good masters and bad masters; extremely kind ones and occasionally cruel ones, though the really cruel or hard master was a marked exception. The conduct of the slaves in the war confirm this. It was not true as sometimes claimed, that every slave was loyal to his master, but the fact that the white master could go into the army, leaving his often lonely and remote farm or plantation, his wife and children, and frequently even money and jewels, in the care of the slave for whose liberty his opponent was fighting, indicates at least that there could have been no widespread hatred of the masters or resentment against them. Usually the relationship between slave and master was a personal one and there was none of that impersonalism which made for the discontent and brutality suffered by the New England factory worker. But if the plantation was of unusual size or if the master owned several of them in different places, this personal relationship might be lost, and the slaves' lives could be made a hell on earth. However, even when a slave was placed in good surroundings there was always the danger of his being sold. The best families prided themselves on not selling their slaves and on not breaking up slave families, but even the best of such owners might fall into circumstances necessitating the sale of the slaves. It is interesting to survey some of the leading articles that appeared in the various newspapers of the country prior to and during the rebellion. It is difficult to determine just how many of these articles are propaganda and how many represent the true feelings of the editors and writers. No doubt the fault was not much in the newspapers themselves but rather in the sources of their information. An interesting article concerning the famous assault by Preston S. Brooke, a member of the House of Representatives from South Carolina, upon Senator Sumner of Massachusetts, appeared in the New York Evening Post, May 23, 1856. The article entitled, "The Outrage On Mr. Sumner" is directed against the Southern Representative and Senator Butler. An excerpt follows: "The friends of slavery at Washington are attempting to silence the members of Congress from the free states by the same modes of discipline which make the slaves units on their plantations. Two ruffians from South Carolina, yesterday made the Senate Chamber the scene of their cowardly brutality. They had armed themselves with heavy canes, and-approaching Mr.Sumner, who was seated in his chair writing, Brooks struck him with his cane a violent blow on the head, which brought him stunned to the floor, and Keith with his weapon kept off the by-standers, while the other Ruffian, Brooks, repeated the blows upon the head of the apparently lifeless victim until his cane was shattered to fragments. Mr. Sumner was conveyed from the Senate Chamber bleeding and senseless, so severely wounded that the physician attending did not think it prudent to allow friends to have access to him. The excuse for this base assault is that Mr. Sumner had in the course of debate spoken disrespectfully of Mr. Butler, a relative of Preston S. Brooks, one of the authors of the outrage. No possible indecorum of language on the part of Mr. Sumner could excuse, much less justify an attack like this; but we have carefully examined his speech to see if it contains any matter which could even extenuate such an act of violence, and we find none. He had ridiculed Mr. Butler's devotion to slavery, it is true, but the weapons of ridicule and contempt in debate is by common consent as fair and allowable weapons as argument. We agree fully with Mr. Sumner that Mr. Butler is a monomaniac in the respect of which we speak; we certainly should place no confidence in any representation he might make which concerned the subject of slavery…… The truth is, that the proslavery party, which rules the Senate, looks upon violence as the proper instrument of its designs. Violence reigns in the streets of Washington; violence has now found its way to the Senate Chamber; In short violence is the order of the day; the North is to be pushed to the wall by it, and this plot will succeed if the people of the free States are as apathetic as the slaveholders are insolent."** It can readily be seen that the author of this article is vehemently opposed to the pro-slavery party, and the article illustrates perfectly the use of the newspaper for political means. An article appeared in the Springfield Republican October 19, 1859, praising the character of John Brown. "The universal feeling is that John Brown is a hero--a misguided and insane man, but nevertheless inspired with a genuine heroism. He has a large infusion of the stern old Puritan element in him." The text of the article appearing in the Springfield Republican December 3, 1859, the day after the execution of John Brown, follows! "John Brown still lives. The great State of Virginia has hung his venerable body upon the ignominous gallows, and released John Brown himself to join the noble army of martyrs.............................. A Christian man hung by Christians for acting upon his convictions of duty--a brave man hung for his chivalrous and self-sacrificing deed of humanity--a philanthropist hung for seeking the liberty of oppressed men. No outcry about violated law can cover up the essential enormity of a deed like this." Editorials such as those above did much to influence the populations of both the North and the South. By appealing to the emotions, sense of morality, and by publishing doubtful stories of atrocities the newspapers, along with the teachings of preachers and political speakers, were able to whip the fighting spirit of people on either side to a feverish pitch. This method of influencing the public opinion of all factions has been employed in. all of the wars since the Civil War and is playing its same role in totalitarian and democratic countries alike.

_____

*Slavery and the Civil War, Southern Review, Autumn, 1938

**This article is thought to be the work of William Cullen Bryant, the editor of the paper at that time.

Friday, December 22, 2006 12:49 AM

From: WL Andrews' Son William Xavier Andrews

I did not have a copy of this paper. Its theme reflects the common view of historians both North and South after the Civil War, a romanticized view of the agricultural South as portrayed in the literature of such Vanderbilt Agrarian writers as Penn Warren and Tate.

If Daddy had been at Vanderbilt thirty years later, the literature would have been much harsher on the South. For those people who claim that slavery was not the major cause of the Civil War, I came across an interesting document when I was at Corinth, Mississippi last year. It was at the Civil War museum there and it was an original copy of Mississippi's declaration of secession in 1861.

Family Members

Advertisement

Advertisement