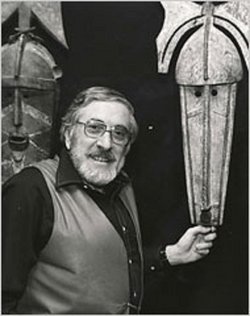

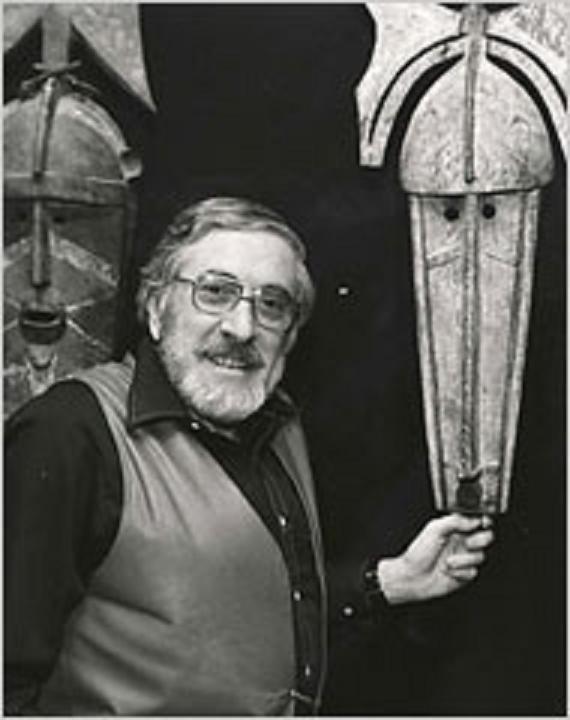

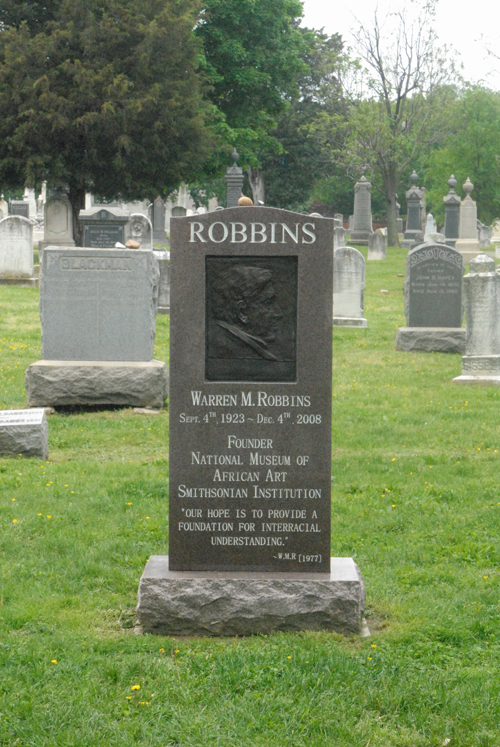

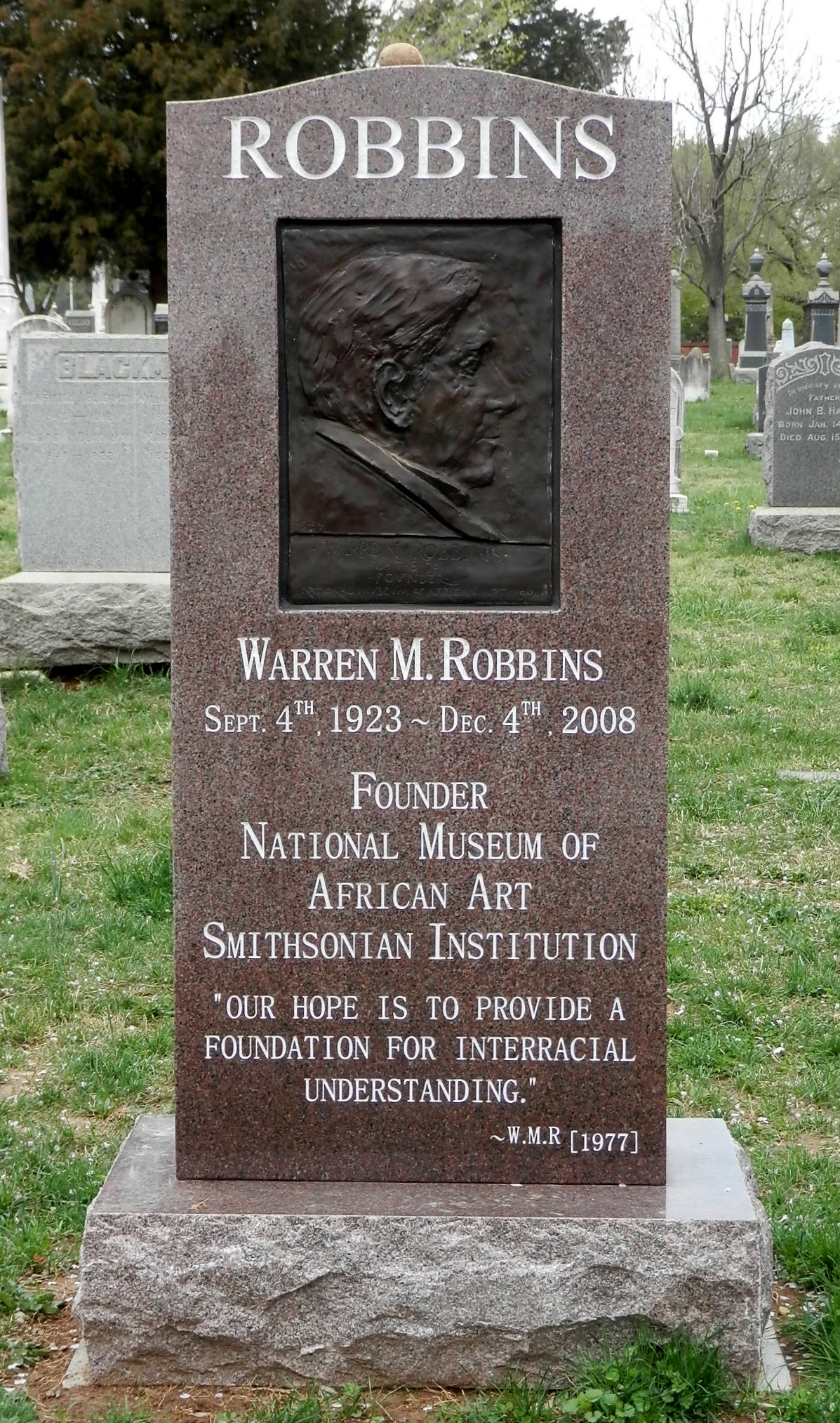

Warren M. Robbins, whose $15 purchase of a carved-wood figure of a man and woman representing the Yoruba people of Nigeria became the seed of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of African Art, died on Dec. 4 in Washington. He was 85 and lived in Washington.

His death was confirmed by Kimberly Mayfield, a spokeswoman for the museum.

Mr. Robbins was a cultural attaché for the State Department when he bought that statue, but not in Africa. He was wandering the streets of Hamburg, Germany, one day in the late 1950s when he stepped into an antiques shop and was smitten by the carved figure. A year later, for $1,000, he bought 32 other pieces of African art — masks, textiles and other figures — at another Hamburg shop.

Only in 1973 did he finally visit the continent whose art had enraptured him. By then he had built a collection of more than 5,000 pieces and had opened a museum with a staff of 20.

At first the museum was just a private project. Mr. Robbins had returned to Washington in 1960 with the original 33 objects, bought a house on Capitol Hill, lined some rooms with tropical plants to evoke rain forests and placed his collection on display.

Soon, he said, "the word got out, in an article in The Washington Post, that there was a crazy guy with an African art collection who had never been to Africa." People started knocking on his door and he welcomed them.

For a time he found some opposition to the idea of a white man operating a museum of art by black people. "I make no apologies for being white," Mr. Robbins told The Post. "You don't have to be Chinese to appreciate ancient ceramics."

By 1963, struck by the idea of creating a real museum, Mr. Robbins bought half of another house on Capitol Hill for $35,000. The abolitionist Frederick Douglass had lived in that house from 1871 to 1877. The first exhibition included Mr. Robbins's collection and two groups of borrowed objects, from the Life magazine photographer Eliot Elisofon and the University of Pennsylvania museum.

As his collection grew, Mr. Robbins raised money and bought the rest of the Douglass house, renaming it the Museum of African Art. He later bought an adjoining town house, then another and another. Eventually he assembled 9 town houses, 16 garages and 2 carriage houses.

In the mid-1970s, concerned about the permanence of his museum, Mr. Robbins began lobbying friends in Congress to have the Smithsonian take over the collection. It did not hurt that his museum had been the site for many of their political fund-raising events. The Smithsonian accepted the collection in 1979, and eight years later it was moved to the National Mall and renamed the National Museum of African Art.

"With little money, through the largess of friends and collectors and an undeterred dream, Robbins established what would become one of the world's pre-eminent museums for exhibiting, collecting and preserving African art," Sharon Patton, the current director of museum, said in a statement on Dec. 8.

The collection, now consisting of about 9,100 objects representing nearly every area of the African continent, includes headdresses, pottery, copper reliefs, musical instruments, baskets, carved-wood maternity figures, objects used by healers, and frightening masks used in ceremonies that mark a boy's passage to manhood. It also houses more than 32,000 volumes on African art, history and culture.

There were interwoven motives for Mr. Robbins's mission to bring African art to the public. One was his support of civil rights; the other was to clarify the influence of African art on Western art.

"I had the feeling that if the public knew what the specialist knew, it could become a foundation for equal regard, for white people to have respect for a significant black people's culture," he told The New York Times in 1987.

Warren Murray Robbins was born in Worcester, Mass., on Sept. 4, 1923, the youngest of 11 children of immigrants from Ukraine. He received his bachelor's degree in English from the University of New Hampshire in 1945 and a master's degree in history from the University of Michigan in 1949. Before becoming a State Department cultural affairs officer, he taught children of Americans living in Europe.

In February Mr. Robbins married Lydia Puccinelli. She is his only immediate survivor.

Mr. Robbins did not just collect African art; sometimes he returned it.

In 1966 a century-old statue of a bearded figure called Afo-A-Kom, regarded as sacred by the people of the tiny West African kingdom of Kom, was stolen from a mountaintop village in Cameroon. Seven years later, after a two-month investigation by The Times, it was found in the possession of a Manhattan gallery owner.

Mr. Robbins raised money to buy the statue, then led the party that brought it back to its homeland. As Nsom Nggue, then the king, received the returned icon, men in brightly colored tribal dress stabbed the air with spears and women, waving fronds, chanted and swayed.

Warren M. Robbins, whose $15 purchase of a carved-wood figure of a man and woman representing the Yoruba people of Nigeria became the seed of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of African Art, died on Dec. 4 in Washington. He was 85 and lived in Washington.

His death was confirmed by Kimberly Mayfield, a spokeswoman for the museum.

Mr. Robbins was a cultural attaché for the State Department when he bought that statue, but not in Africa. He was wandering the streets of Hamburg, Germany, one day in the late 1950s when he stepped into an antiques shop and was smitten by the carved figure. A year later, for $1,000, he bought 32 other pieces of African art — masks, textiles and other figures — at another Hamburg shop.

Only in 1973 did he finally visit the continent whose art had enraptured him. By then he had built a collection of more than 5,000 pieces and had opened a museum with a staff of 20.

At first the museum was just a private project. Mr. Robbins had returned to Washington in 1960 with the original 33 objects, bought a house on Capitol Hill, lined some rooms with tropical plants to evoke rain forests and placed his collection on display.

Soon, he said, "the word got out, in an article in The Washington Post, that there was a crazy guy with an African art collection who had never been to Africa." People started knocking on his door and he welcomed them.

For a time he found some opposition to the idea of a white man operating a museum of art by black people. "I make no apologies for being white," Mr. Robbins told The Post. "You don't have to be Chinese to appreciate ancient ceramics."

By 1963, struck by the idea of creating a real museum, Mr. Robbins bought half of another house on Capitol Hill for $35,000. The abolitionist Frederick Douglass had lived in that house from 1871 to 1877. The first exhibition included Mr. Robbins's collection and two groups of borrowed objects, from the Life magazine photographer Eliot Elisofon and the University of Pennsylvania museum.

As his collection grew, Mr. Robbins raised money and bought the rest of the Douglass house, renaming it the Museum of African Art. He later bought an adjoining town house, then another and another. Eventually he assembled 9 town houses, 16 garages and 2 carriage houses.

In the mid-1970s, concerned about the permanence of his museum, Mr. Robbins began lobbying friends in Congress to have the Smithsonian take over the collection. It did not hurt that his museum had been the site for many of their political fund-raising events. The Smithsonian accepted the collection in 1979, and eight years later it was moved to the National Mall and renamed the National Museum of African Art.

"With little money, through the largess of friends and collectors and an undeterred dream, Robbins established what would become one of the world's pre-eminent museums for exhibiting, collecting and preserving African art," Sharon Patton, the current director of museum, said in a statement on Dec. 8.

The collection, now consisting of about 9,100 objects representing nearly every area of the African continent, includes headdresses, pottery, copper reliefs, musical instruments, baskets, carved-wood maternity figures, objects used by healers, and frightening masks used in ceremonies that mark a boy's passage to manhood. It also houses more than 32,000 volumes on African art, history and culture.

There were interwoven motives for Mr. Robbins's mission to bring African art to the public. One was his support of civil rights; the other was to clarify the influence of African art on Western art.

"I had the feeling that if the public knew what the specialist knew, it could become a foundation for equal regard, for white people to have respect for a significant black people's culture," he told The New York Times in 1987.

Warren Murray Robbins was born in Worcester, Mass., on Sept. 4, 1923, the youngest of 11 children of immigrants from Ukraine. He received his bachelor's degree in English from the University of New Hampshire in 1945 and a master's degree in history from the University of Michigan in 1949. Before becoming a State Department cultural affairs officer, he taught children of Americans living in Europe.

In February Mr. Robbins married Lydia Puccinelli. She is his only immediate survivor.

Mr. Robbins did not just collect African art; sometimes he returned it.

In 1966 a century-old statue of a bearded figure called Afo-A-Kom, regarded as sacred by the people of the tiny West African kingdom of Kom, was stolen from a mountaintop village in Cameroon. Seven years later, after a two-month investigation by The Times, it was found in the possession of a Manhattan gallery owner.

Mr. Robbins raised money to buy the statue, then led the party that brought it back to its homeland. As Nsom Nggue, then the king, received the returned icon, men in brightly colored tribal dress stabbed the air with spears and women, waving fronds, chanted and swayed.

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement