A bullet fired carelessly from a comrade's gun threatened to end Pvt. August Scherneckau's enlistment as a Union soldier and perhaps his life. He was wounded in the leg on March 31, 1864, while he and other men of the First Nebraska Volunteer Cavalry guarded a steamboat that had run aground on the White River of northeastern Arkansas. In the weeks since the Nebraskans marched into nearby Batesville on Christmas Day 1863, they had been engaged in a vicious little war with Confederate soldiers and partisans for control of the Arkansas countryside, its hamlets, and its waterways.

Scherneckau (shure-nuh-cow) lay bedfast in a series of makeshift hospitals until mid-June, when many of the First Nebraska soldiers were recalled from the fighting and sent home on furlough as their reward for reenlisting. He accompanied the Nebraska veterans on the steamboat ride to St. Louis, and then made his way back to Grand Island City, his home since 1858 when the young immigrant from Holstein joined his uncle, Fred Hedde, and other Germans who had established a settlement in Nebraska Territory. By the time Scherneckau had recovered from his wound and returned to his regiment in February 1865, the men of the First Nebraska Veteran Volunteer Cavalry were fighting a new war against a new foe in a new locale: Cheyenne, Sioux, and Arapaho warriors in Nebraska's Platte Valley.

Protecting the overland travel and communications corridor extending along the Platte and over the Rockies to the West Coast had posed a problem for the federal government from the outbreak of the Civil War. While the war continued, only a handful of Union volunteers could be spared for service in the West. Roaming Indian raiders were the main threat, particularly after an 1862 uprising of the Minnesota Sioux and the army's subsequent punitive campaigns in Dakota Territory sparked resentment among the Plains tribes. When warriors swept eastward along the Platte and Little Blue valleys in early August 1864, killing settlers and travelers and leaving road ranches and stagecoach stations as smoking ruins, it was clear more soldiers were needed.

The First Nebraska veterans had expected to return to Arkansas when their furlough expired, to rejoin the recruits and non-veterans who remained behind. But the Indian raids finally prompted the War Department's agreement to pleas that Nebraska officials had been making since 1861. The territory's volunteer soldiers should be kept at home. Accordingly, the First Nebraska was ordered to reassemble in Omaha, from which it marched in late August 1864 to garrison Forts Kearny, Cottonwood, and several tiny outposts scattered along the Platte.

The soldiers' principal task was protecting the transcontinental telegraph line and overland stagecoach stations, escorting the coaches, and keeping open the Platte River Road for the freight wagons essential to supplying military posts and civilian settlements in the trans-Missouri West. The U.S. mail also had to go through. This duty was marked by exhausting riding, billowing dust, tormenting insects, chilling winds, numbing boredom, and an occasional dash after Indians, whom the soldiers rarely caught. Platte Valley service offered even less romance and recognition than had the sporadic hide-and-seek skirmishing with Confederate bushwhackers in the Arkansas woods and bayous. The men of the First Nebraska would get no respite from the wearisome and lonely assignment until the last of them were finally mustered out in July 1866, their Civil War ending months after the last Confederate armies had surrendered.

While many soldiers in the "big war" east of the Missouri recorded their experiences in letters and diaries, personal accounts from the Plains Indian campaigns of the 1860s are far less common. August Scherneckau's diary is an exception that proves the rule. Beginning with his October 1862 enlistment in the First Nebraska and continuing until he was mustered out in October 1865 when his term was up, he wrote almost daily in his diary, except for the few months he was at home recovering from his wound. He kept it largely for the benefit of his relatives and friends in the Grand Island settlement, so they could see the war through his eyes. Scherneckau's account of his three years with the First Nebraska is the richest and most detailed record of a Nebraska soldier's Civil War service that has come to light, with the added bonus of having been written from the perspective of a recent German immigrant. The majority of Scherneckau's wartime diary, covering the First Nebraska's service in Missouri and Arkansas from 1862 to 1864, was published in 2007 as Marching With the First Nebraska: A Civil War Diary, translated from the German by Edith Robbins and edited by Robbins and James E. Potter. Due to the diary's length and its shift in focus and locale during 1865, the book summarized Scherneckau's Platte Valley experiences and the observations he recorded during the final months of his enlistment.

As a document that provides new details on an important, but often overlooked part of the story of Nebraska's Civil War soldiers, the 1865 diary deserves publication in full. It began when Scherneckau left Grand Island on February 23, 1865, to rejoin his regiment. Five days later he was reunited with his Company H comrades at Midway Station, located at William Peniston and Andrew J. Miller's ranche, some sixty miles west of Fort Kearny. Nearby was a station for Ben Holladay's Overland Stage Company, which was the primary reason soldiers were posted there.

From his vantage point at Midway and from horseback as he rode along the trail, Scherneckau observed a constant parade of stagecoaches, freighting contractors' "bull trains," and emigrant wagons passing up and down the Platte Valley. He witnessed the buildup for Gen. Patrick E. Connor's 1865 Powder River campaign against the Indians, saw the comings and goings of volunteer regiments, and noted important passersby, both military and civilian. The seemingly endless procession provided daily fodder for his pen. He also described the Platte Valley landscape, the military posts, the occasional foray in pursuit of elusive warriors, and the rigors of soldier life.

Upon leaving the army Scherneckau returned to Grand Island, but he soon moved to Oregon, where he spent most of the rest of his life.

In 1984 his Civil War diary was deposited at the Oregon Historical Society in Portland. The Society generously granted permission for its publication, first as Marching With The First Nebraska, and now as this article.

The complete diary appears in the Spring 2010 issue.

August Scherneckau and his wife Cicilia settled in Cross Hollows, Oregon (1/2 mile south of Shaniko, Hwy. 218) in 1874. In May, 1879 Scherneckau opened the first post office and became the first Postmaster. Scherneckau built a store, a saloon, and a 16 room inn at Cross Hollows. Native American Indians pronounced Scherneckau as "Shaniko" and this was the name given to the plat in 1899 which became the terminus for the Southern Columbia RR and the largest wool shipping enterprise in the world from circa 1901 to 1911. Derived from Rees, Helen Guyton, "Shaniko: Wool Capital to Ghost Town" and "Shaniko People" (Portland OR : Binford & Mort, 1982)

A bullet fired carelessly from a comrade's gun threatened to end Pvt. August Scherneckau's enlistment as a Union soldier and perhaps his life. He was wounded in the leg on March 31, 1864, while he and other men of the First Nebraska Volunteer Cavalry guarded a steamboat that had run aground on the White River of northeastern Arkansas. In the weeks since the Nebraskans marched into nearby Batesville on Christmas Day 1863, they had been engaged in a vicious little war with Confederate soldiers and partisans for control of the Arkansas countryside, its hamlets, and its waterways.

Scherneckau (shure-nuh-cow) lay bedfast in a series of makeshift hospitals until mid-June, when many of the First Nebraska soldiers were recalled from the fighting and sent home on furlough as their reward for reenlisting. He accompanied the Nebraska veterans on the steamboat ride to St. Louis, and then made his way back to Grand Island City, his home since 1858 when the young immigrant from Holstein joined his uncle, Fred Hedde, and other Germans who had established a settlement in Nebraska Territory. By the time Scherneckau had recovered from his wound and returned to his regiment in February 1865, the men of the First Nebraska Veteran Volunteer Cavalry were fighting a new war against a new foe in a new locale: Cheyenne, Sioux, and Arapaho warriors in Nebraska's Platte Valley.

Protecting the overland travel and communications corridor extending along the Platte and over the Rockies to the West Coast had posed a problem for the federal government from the outbreak of the Civil War. While the war continued, only a handful of Union volunteers could be spared for service in the West. Roaming Indian raiders were the main threat, particularly after an 1862 uprising of the Minnesota Sioux and the army's subsequent punitive campaigns in Dakota Territory sparked resentment among the Plains tribes. When warriors swept eastward along the Platte and Little Blue valleys in early August 1864, killing settlers and travelers and leaving road ranches and stagecoach stations as smoking ruins, it was clear more soldiers were needed.

The First Nebraska veterans had expected to return to Arkansas when their furlough expired, to rejoin the recruits and non-veterans who remained behind. But the Indian raids finally prompted the War Department's agreement to pleas that Nebraska officials had been making since 1861. The territory's volunteer soldiers should be kept at home. Accordingly, the First Nebraska was ordered to reassemble in Omaha, from which it marched in late August 1864 to garrison Forts Kearny, Cottonwood, and several tiny outposts scattered along the Platte.

The soldiers' principal task was protecting the transcontinental telegraph line and overland stagecoach stations, escorting the coaches, and keeping open the Platte River Road for the freight wagons essential to supplying military posts and civilian settlements in the trans-Missouri West. The U.S. mail also had to go through. This duty was marked by exhausting riding, billowing dust, tormenting insects, chilling winds, numbing boredom, and an occasional dash after Indians, whom the soldiers rarely caught. Platte Valley service offered even less romance and recognition than had the sporadic hide-and-seek skirmishing with Confederate bushwhackers in the Arkansas woods and bayous. The men of the First Nebraska would get no respite from the wearisome and lonely assignment until the last of them were finally mustered out in July 1866, their Civil War ending months after the last Confederate armies had surrendered.

While many soldiers in the "big war" east of the Missouri recorded their experiences in letters and diaries, personal accounts from the Plains Indian campaigns of the 1860s are far less common. August Scherneckau's diary is an exception that proves the rule. Beginning with his October 1862 enlistment in the First Nebraska and continuing until he was mustered out in October 1865 when his term was up, he wrote almost daily in his diary, except for the few months he was at home recovering from his wound. He kept it largely for the benefit of his relatives and friends in the Grand Island settlement, so they could see the war through his eyes. Scherneckau's account of his three years with the First Nebraska is the richest and most detailed record of a Nebraska soldier's Civil War service that has come to light, with the added bonus of having been written from the perspective of a recent German immigrant. The majority of Scherneckau's wartime diary, covering the First Nebraska's service in Missouri and Arkansas from 1862 to 1864, was published in 2007 as Marching With the First Nebraska: A Civil War Diary, translated from the German by Edith Robbins and edited by Robbins and James E. Potter. Due to the diary's length and its shift in focus and locale during 1865, the book summarized Scherneckau's Platte Valley experiences and the observations he recorded during the final months of his enlistment.

As a document that provides new details on an important, but often overlooked part of the story of Nebraska's Civil War soldiers, the 1865 diary deserves publication in full. It began when Scherneckau left Grand Island on February 23, 1865, to rejoin his regiment. Five days later he was reunited with his Company H comrades at Midway Station, located at William Peniston and Andrew J. Miller's ranche, some sixty miles west of Fort Kearny. Nearby was a station for Ben Holladay's Overland Stage Company, which was the primary reason soldiers were posted there.

From his vantage point at Midway and from horseback as he rode along the trail, Scherneckau observed a constant parade of stagecoaches, freighting contractors' "bull trains," and emigrant wagons passing up and down the Platte Valley. He witnessed the buildup for Gen. Patrick E. Connor's 1865 Powder River campaign against the Indians, saw the comings and goings of volunteer regiments, and noted important passersby, both military and civilian. The seemingly endless procession provided daily fodder for his pen. He also described the Platte Valley landscape, the military posts, the occasional foray in pursuit of elusive warriors, and the rigors of soldier life.

Upon leaving the army Scherneckau returned to Grand Island, but he soon moved to Oregon, where he spent most of the rest of his life.

In 1984 his Civil War diary was deposited at the Oregon Historical Society in Portland. The Society generously granted permission for its publication, first as Marching With The First Nebraska, and now as this article.

The complete diary appears in the Spring 2010 issue.

August Scherneckau and his wife Cicilia settled in Cross Hollows, Oregon (1/2 mile south of Shaniko, Hwy. 218) in 1874. In May, 1879 Scherneckau opened the first post office and became the first Postmaster. Scherneckau built a store, a saloon, and a 16 room inn at Cross Hollows. Native American Indians pronounced Scherneckau as "Shaniko" and this was the name given to the plat in 1899 which became the terminus for the Southern Columbia RR and the largest wool shipping enterprise in the world from circa 1901 to 1911. Derived from Rees, Helen Guyton, "Shaniko: Wool Capital to Ghost Town" and "Shaniko People" (Portland OR : Binford & Mort, 1982)

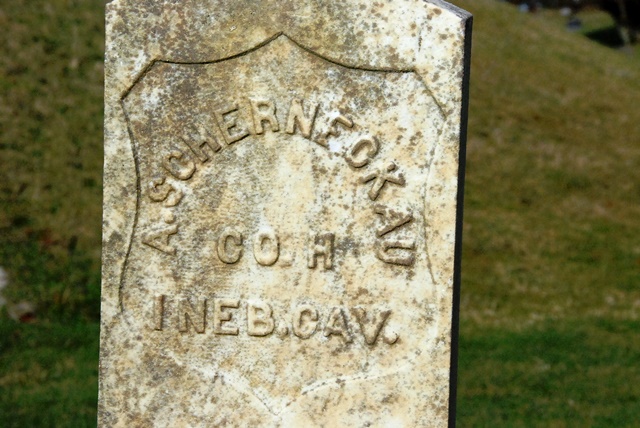

Inscription

Co. H, 1st NE Cav

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement