As eastern ports were closed, he probably came into the US thru' New Orleans and proceeded to Texas c.1836 where he lived as a hunter until going with Army as (civilian) color sergeant and enlisting (by Albert Tracy of Maine) at Castle Perote, Mexico during the Mexican War.

After getting out at Rhode Island, he went up into Maine with Tracy & others, remarried, but was found in the 1850 census gold-mining in Calaveras, California; returning to Maine, Powell was commissioned a 2nd lieutenant in 1855 and headed back to Texas and Indian Territory/Oklahoma, where he conducted Indian peace treaties and oversaw the construction of what became known as Powell Road into Fort Smith, Arkansas while becoming good friends with the family of famed artist Vinnie Ream, who later sculpted the US Capitol Rotunda statue of Abraham Lincoln and much else...remaining with the Army until his death.

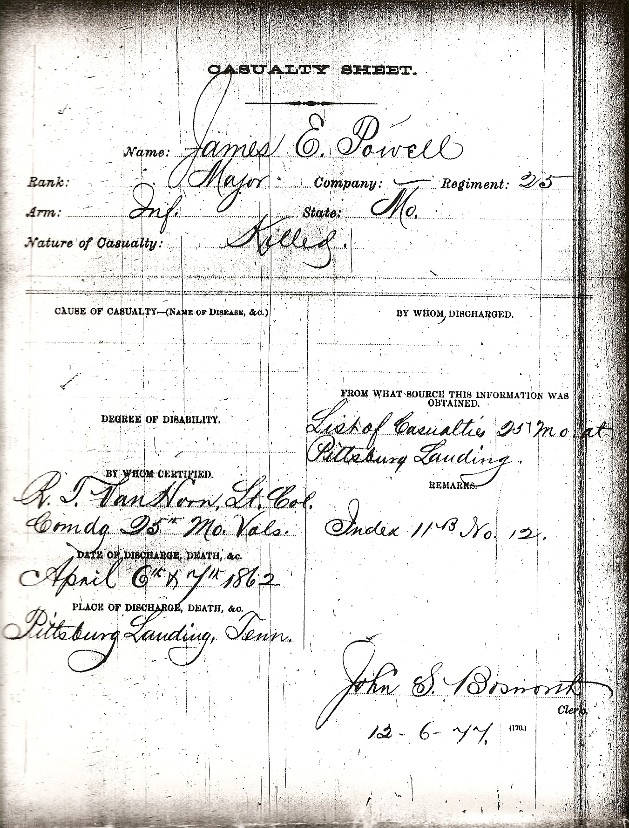

Evidently the most central participant in the Battle of Shiloh who was KIA and is also buried there. Officer in 1st Infantry, Regular Army of the United States, detached to 25th Missouri on 24MAR1862.

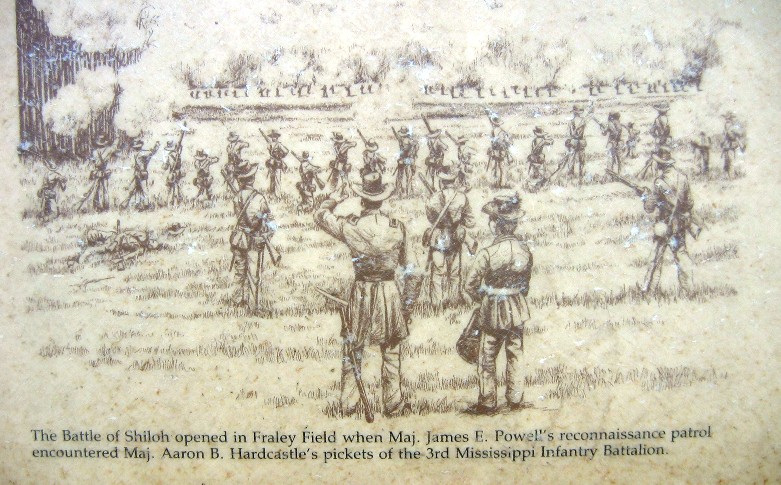

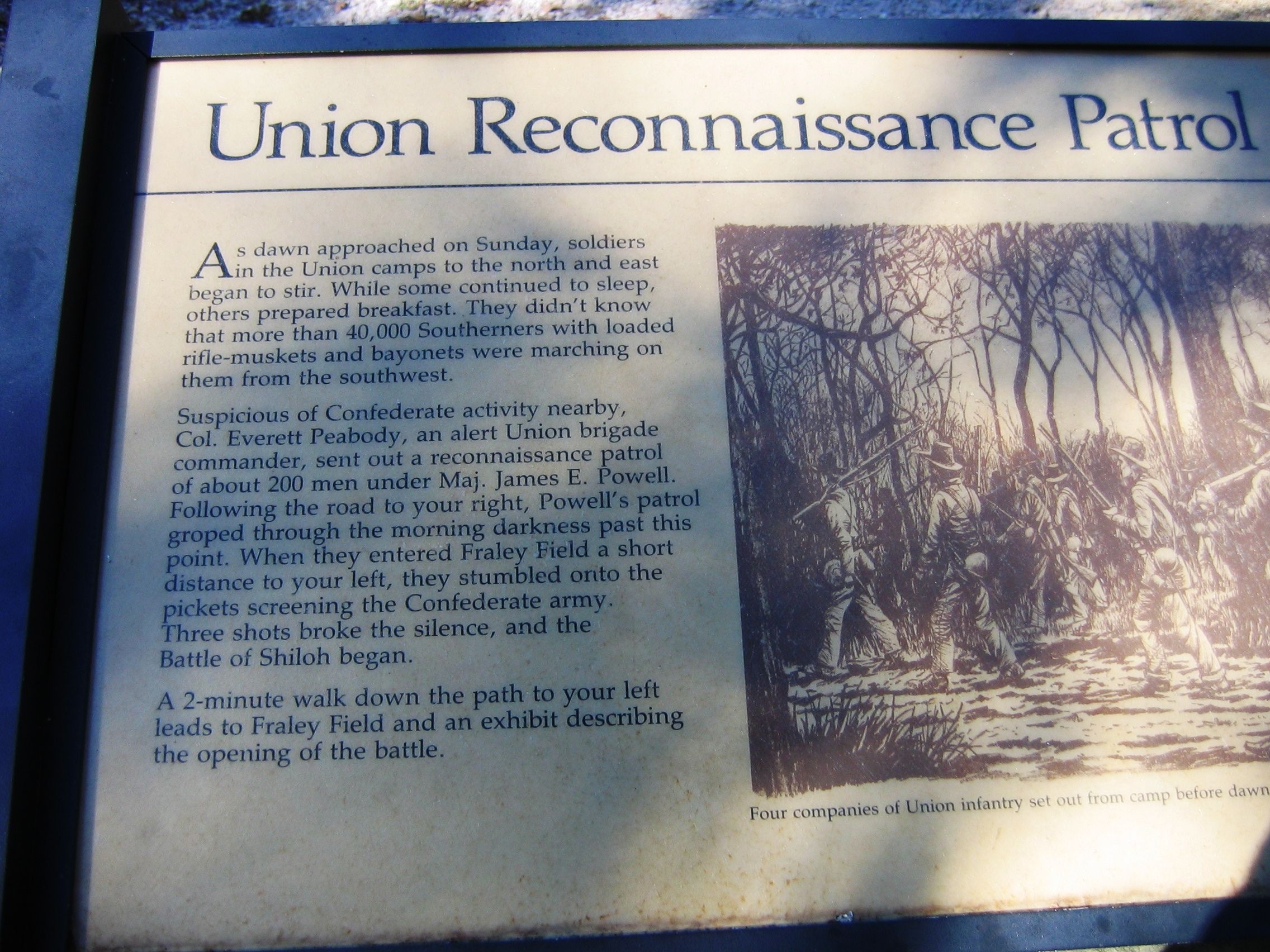

After noticing 'butternuts' watching Union parade, Major Powell was sent out by COL Everett Peabody (KIA Shiloh, but buried in family plot; Springfield, MA) both to reconnoiter the evening of 05APR1862 and to lead the morning patrol 06APR1862 as described/pictured on the Fraley Field marker where the Battle of Shiloh (Pittsburg Landing) began.

Colonel Peabody took it upon himself to issue this order, and incurred the wrath of General Prentiss for same; since both Peabody and Powell died that day, they filed no after-action reports and were basically overlooked for their acts as unsung heroes in saving the Union, which researchers and writers have brought back to light by combing official records in more recent years.

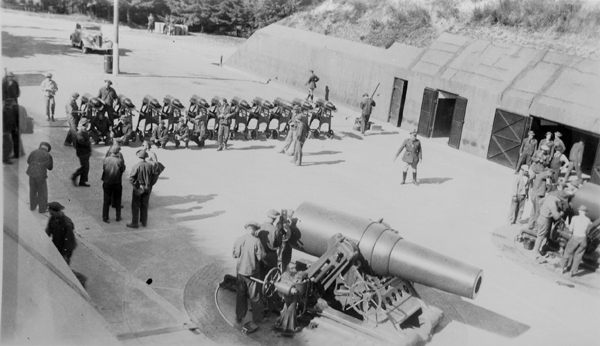

Battery James Powell (1901 - 1943), one of the four coastal artillery batteries located at Fort Worden, Washington to protect Puget Sound, was named for him.

J. E. Powell was hit eleven times through the day of 06APR1862 and finally mortally wounded while walking at head of his command in the Sunken Road...first-hand account by Charles Morton: "A few hundred yards to the rear we put him in an ambulance. He enjoined us to return to the firing line and do our best, that every man was needed. He was shot in the side and died that night, patriotic, cool, and brave to the last."

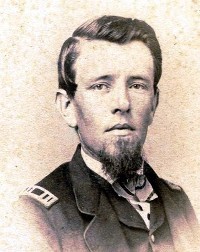

Buried at Shiloh officially "unknown," but most likely in Officers' Circle #3582 per grave notes including "said to have been a major" ~ Powell had been promoted just a couple weeks earlier and did not have the proper Major epaulet ranks to wear; last picture, here included, shows him with Captain ranks ~ learned from (then) Shiloh Park Ranger Timothy Smith on two-year mission by family to disinter the lost facts of Major Powell's life.

Brigadier General Charles Morton’s eye-witness account, given at 50th Anniversary reunion in 1912, of what happened to 25th Missouri at Shiloh:

"The colonel was Everett Peabody, a strikingly handsome man of massive build and commanding presence, a native of Massachusetts, a graduate from Harvard, and a civil engineer by profession, in which he had risen to considerable prominence.

"Our major was James E. Powell, a captain of the 1st U. S. Infantry, a modest, cool-headed, capable, brave officer, who endeared himself to the hearts of all during the few days he was with us.

"I entered the service with the company by being rated a musician, and although I was not then, and have never been since, able to torture from any instrument a musical note, I had to perform for several months the orderly duty of a musician, and thus became familiar with officers and what was transpiring at regimental headquarters. Then for some time I was in charge of collecting and distributing the mail of the regiment, and came in contact, and became pretty well acquainted, with nearly every officer and man in it. The life was new to me, and intensely interesting; the events were thrilling; I was young, and my mind was susceptible of deep and lasting impressions. Nearly every man of the original company who did not fall in battle, die of wounds or disease, or was not discharged for disability received a commission. Thus it was decimated or scattered.

"Soon after my discharge, I was practically imprisoned for four years at West Point, and then at once ordered to New Mexico, and until recent years I have served almost continuously beyond the western frontier and have had but little or no opportunity to talk over with comrades the incidents of this battle. Soon after I commenced to read the post-bellum accounts of it, I wrote out my own experience, and the incidents I recount to-night are taken from that narrative. Since then I have met my three brothers who were in the regiment and battle, and I asked each in turn to give me his version on certain points; and they differed materially in nothing that is in this paper. Now I have no axe to grind here, and I would detract not one iota from the name, fame, or laurels of any man. My experience has been that about all do their very best in battle; and I have no sympathy with fireside military critics, after the fact. I took the humble and insignificant part of a private soldier in the great battle, and am content with that honor, but I would like to see a full and correct account of it recorded in history.

"You know that it is generally understood that our Army was completely surprised, and that the advance, or 6th Division, commanded by Gen'l Benj. M. Prentiss, fled from their beds before the enemy and most of them were captured. This is entirely incorrect.

"A few years since I met Col. R. T. Van Horn, Member of the House of the last Congress, and since the war editor-in-chief of the Kansas City Journal of Commerce. I asked him why as a literary man he did not write a detailed account of the attack and battle. He said he made his report as commander of the regiment immediately after the battle, and that it was on file in Washington. In that city, later, I asked Colonel Scott, in charge of the publication of the Rebellion Records, to let me read the report. In a large hand it covered less than a sheet of paper, written in a sacked camp, when all were tired and exhausted and the numbers of killed, wounded, and missing were not accurately known, — and it gave very few details.

"The regiment was reorganized after being paroled at the siege of Lexington (Note: James Powell was not at Lexington as he was then still in the REGULAR Army of the United States…not detached to 25th Missouri until 26MAR1862), and was at Benton Barracks, near St. Louis, drilling vigorously, when the news of the fall of Forts Henry and Donelson and the battle of Pea Ridge in rapid succession reached us, creating intense enthusiasm and a burning desire on the part of all to have a hand in the work of war, so favorably begun after the long weary months of waiting — in fact, discouraging inactivity. Indeed, they were about the first substantial successes of the Union arms. None who lived at the North at the commencement of the war, surrounded by patriotic influences, can understand what the loyal people of the border slave States had to undergo and endure for their loyalty at the hands of secessionists. Our surrender at Lexington after the long and trying siege, though honorable and creditable in the eyes of the government and the people, was humiliating to the regiment itself, and it longed, not only from hatred caused by persecution, but also from a feeling of revenge, to meet the enemy in a more equal contest.

"So great joy and hilarity ran through the regiment when orders came for it to move, though the men knew not whither. March 26th it was escorted by several regiments and a band through the streets of St. Louis, and boarded the steamer Continental. At Cairo we turned up the Ohio, and all began to smell our course and probable destination. A short stop was made at Paducah and General Prentiss and staff came on board. When we turned up the Tennessee, all knew we were bound for the heart of Dixie's land, and that song, modified to more appropriate words, was a constant refrain. When the recent captured works of Fort Henry, built to bar any such invasion, hove in sight, a prolonged and general shout rent the air. We viewed with much satisfaction the Union soldiers manning the guns as we sped by, and we gave them cheer after cheer.

"On we ploughed up the beautiful river, halting briefly at Savannah, the headquarters of the assembling Army, for General Prentiss and our colonel to report to Gen. C. F. Smith, for, be it remembered, that the Council of War that placed General Grant in command was not held until April 2d, practically but three days before the battle. Eight miles above we stopped at Pittsburg Landing, just at dark, March 28th. The 29th we disembarked, and Sunday, the 30th, just one week before the battle, the regiment marched past the camps of the other troops, towards Corinth, some four miles from the Landing, and went into camp perpendicularly to the road. Within three or four days other regiments arrived, extending the line to the left, forming two brigades of the 6th Division, leaving my regiment on the right, and therefore, the first of the First Brigade. Our colonel, Peabody, commanded this brigade, and my captain, Donnelly, was detail acting assistant adjutant-general. As our first lieutenant was acting regimental quartermaster temporarily and the second lieutenant was an inexperienced boy, the Captain exercised also supervision of the company, and kept it busy in camp instruction, even giving it target practice. And, it was said, he urged that rifle-pits be made and the camp prepared for defense.

"On Wednesday the 2d, a part of the regiment was sent out one-and-a-half or two miles in the direction of Corinth, on picket duty. Keeping vigilance that night, I saw the heavens illuminated by the Confederate camp-fires. We were astounded at the proximity and apparently great numbers of the enemy. Our men, visiting the farm-houses nearby, were warned that they ran great risk of capture, that the Confederate cavalry was scouring the neighborhood. It was thought at first that this was simply said to keep them away; but they were warned at every house.

"That afternoon, Thursday, we were relieved by another detail; but the men who returned to camp on Friday after noon, reported that no detail had relieved them, and that there was no picket whatever on that road between us and the enemy. If we were not aware of the dense ignorance of all, at that time, on military matters, particularly of practical soldiering, we could attribute this neglect only to traitorous design. There was considerable cavalry in the command, why was it not screening our camp, and even feeling the enemy in his own? Simply ignorance.

"We had no generals but in rank and authority. I say this not in disparagement of any who were there, but as a fact. When they learned their business, in the only school for generals, the great practical school of war, many of them won a place among the very greatest generals the world has ever produced. The Grant and Sherman of 1864 would have relieved for utter inefficiency generals of no more skill than the Grant and Sherman at Shiloh.

"On Saturday afternoon the whole 6th Division, but the camp guard, was reviewed in a field near General Prentiss's headquarters; and the rumor, afterwards confirmed, went through the camp that night that a detachment of Confederate cavalry rode up to the edge of the field and witnessed the review. At retreat, Captain Donnelly, though adjutant of the brigade, came to the company and said that the enemy was marching on the camp in force, and was within fourteen miles; there would be a battle, and he wanted to see I Company ready. He inspected the arms, equipments, and ammunition carefully, and gave instruction and advice. We were required to lie, I will not say sleep, on our arms. Whence came this information I do not know. There was no secrecy, the whole regiment anticipated a battle. Some of the officers sat up late, and others remained up all night. Among the latter was Colonel Peabody, who communicated with General Prentiss that evening, and expressed his belief that preparations should be made for an energetic defence. So accurate was his information, or correct his conviction, that during the night he ordered the two reliefs of the brigade guard not on post to patrol the front under Major Powell, field officer of the day. This developed a force believed to be the enemy's picket. As a vigilant commander, the Colonel upon getting the information sent out three companies of the regiment under Powell: B, Captain Joseph Schmitz, and E, Captain Simon S. Evans, the two companies that stormed the hospital building at Lexington; and H, Captain Hamilton Dill, a soldier of the Mexican War. They drove in the enemy's picket, and developed his main force about one and a half miles from our camp. The Colonel then sent out a part of the 21st Missouri Infantry to reinforce Major Powell's command, and in the engagement that followed Colonel Moore lost a leg.

"At daybreak wounded were being brought into camp, and the companies were formed in their streets prepared for battle. No orders coming from division headquarters, Colonel Peabody ordered the "long roll" beaten, and the regiment formed in line. The alarm was taken up by regiment after regiment and spread throughout the Army. Shortly General Prentiss came riding rapidly down the line to our Colonel, jerked up his horse, and with great earnestness, if not great anger, exclaimed: "Colonel Peabody, I will hold you personally responsible for bringing on this engagement." The Colonel, with severe dignity and illy concealed contempt, answered in his clear, strong voice: "General Prentiss, I am personally responsible for all my official acts." This stormy interview was seen, if the words were not heard, by hundreds of men; and my brother Marcus, later a lieutenant of the regiment and captain in the 43d Missouri Infantry, was orderly for the Colonel at the time, and both heard and saw what occurred.

"Each regiment of the brigade moved at once directly to the front to support Colonel Moore and meet the enemy in advance of our camp. The line was an echelon led by my regiment, which halted between half and three quarters of a mile out, a little in rear but considerably to the right of Colonel Moore's skirmish line.

"I will digress to say that the guns of the only battery in the division had not arrived. The personnel and horses were camped on the right of the brigade. Some three-fourths of a mile to the right of this gunless battery was the left of Sherman's division, its right somewhat advanced. Opposite this interval, to the front but nearer Sherman's left, was Shiloh church, a mere log country meeting-house.

"To resume: The regiment was standing at rest. The skirmishing and the fact that the next regiment came up overlapping our left, causing some confusion, diverted attention in that direction. Looking to the front again, I saw, coming down a gentle slope within easy range the Confederates massed many lines deep. Reflect for one moment upon the profound ignorance of war, — two hostile armies hunting each other without a skirmish line or advance of any kind. Lieut. Col. R. T. Van Horn, our regimental commander, gave the commands: "Attention, battalion — ready — aim — fire!" The moving mass was decimated and staggered. Its heavy loss, its very density, prevented a vigorous reply. A heavy fire was poured upon them in their deployment. But soon our men commenced to fall thick and fast. Then we sought the shelter of the trees for we were in heavy oak timber, pretty free from under brush. This position was held until our unsupported right and left were being turned when we fell back from tree to tree to avert being enveloped. Every step was stubbornly disputed. Our men were mostly hunters who would have scorned shooting a squirrel or wild turkey but through the head, and were cool. The "Johnnies" yelled vociferously "Bull Run, Bull Run!" and our men shouted back defiance — "Why don't you come on?" Indeed the withering fire they received at first, made them chary of pressing us, and we could hear and see the efforts of their officers urging them on. These were among the first casualties on the field, and doubtlessly the wounded and many of the killed were carried off, but the number of dead found here after the battle was appalling.

"Thus we resisted the advance of the enemy until our color-line was reached. With all that was at stake before, now we had our camp to defend. Here we had had our daily dress-parades and pomp of war; now had come the circumstance. Colonel Peabody, always electrifying, was doubly so now. We were not whipped, but simply out numbered. With a look of mortified pride but great determination on his handsome face he conjured the men to hold their ground. Pointing to the words in golden letters on our flag, he cried out: "Lexington, men; Lexington; remember Lexington!" (again be reminded that James Powell was NOT at Lexington because he was then still in the Regular Army of the United States, not yet detached to the 25th Missouri).

"How long we held the enemy at bay at this line I cannot say; it is beyond the range of human skill to estimate accurately the flight of time in battle. Behind trees in the company streets, and simply tents that screened us from sight, we kept up a constant fire. The enemy could not dislodge us. He dared not charge over the comparatively open ground between us, and for the same reason, as well as because of our disorganized condition and his vastly superior numbers, we could not charge him; but we held him at musket range, and expected momentarily support. We thought we had him permanently checked and would soon drive him back. Since the battle was on, the entire Army could have assembled on our line had it followed the simple maxim of war: "In the absence of orders, march to the sound of battle." And we longed for field guns to start him back and lamented they did not come. There was a perceptible lull in the roar of musketry at the left, and my attention was diverted from the front by a rifle-ball striking a tree and filling the right side of my neck with small pieces of oak bark. Stung by the sharp pain and enthused by seeing a dun-horse battery coming from the left at full run, I exclaimed; "We will give them hell now, a battery is coming!" My brother William had hardly finished chiding me for using such language, when it whirled into battery about two hundred yards away and opened upon us with grape and canister. Horror of horrors! Even ahead of the deafening reports of the gun came a storm of missiles screaming and shrieking through the air, ripping through tents, smashing tentpoles, knocking from the trees limbs that rained upon us, tearing up the ground, and raising a blinding dust. Crash — crash — came in rapid succession the showers of iron hail. A solid shot plunged through a tree and a shell burst in a mud bake-oven and covered us with a cloud of dust and beat us with clods and splinters. We couldn't help it, we had to let go.

"Could these be the guns whose reports carried the first tidings of the battle to Grant, at the breakfast-table at Savannah, twelve miles away?

"Just in the rear of the line of field officers' tents, a knot of us made another stand. Here Colonel Peabody's horse passed us, riderless and stirrups flapping in the air. We knew our brave and noble Colonel had fallen. His body was found nearby after the battle, and subsequently it was sent to Springfield, Massachusetts. In the cemetery there, a monument, draped with his country's flag, bearing the words — "Lexington, Shiloh, 25th Mo. Vol. Inf'y" — all cut in marble, marks his grave — the grave of the hero of Shiloh, — the man whose devotion cost him his life, whose vigilance, energy, and bravery saved the Army from utter surprise and defeat and the Union cause from all the far-reaching consequences. Probably no man of our Armies, in our entire history, rendered his country at one time more valuable service, and yet, outside the few survivors of his regiment, his name is hardly known, and is unhonored and unsung.

"Here this paper should properly end, for its main object is to give some of the circumstances attending the attack and shoving back of the 6th Division. But as I desire to make a few comments on, I will not say criticise, the battle, and as my story proper is not long, I will continue to presume upon your patience.

"Our little party was soon approached by Captain Donnelly, the brigade adjutant, who demanded with some asperity to know why we had not obeyed the order to retire, directed us to do so, and pointed to the rear, towards Hurlbut's division, as where our division was forming. We had simply heard no orders. We soon came to an open field, and as both flanks had been turned, to turn to the right or left meant certain death or capture. We must cross the open ground. A few rods out, and whiz — whiz — whiz! — the bullets cut the air. Zip — zip — zip! — they ricocheted by our sides to the front. None hit me, but they excited wonderfully my power of propulsion, and I believe my fortune would be assured as a sprinter now, if I could only find some equally effective promoter of locomotion.

"Behind a high rail fence, on low ground in dense under brush, we found the remnants of the regiment and brigade assembled in line. Soon a terrific artillery duel commenced, from the enemy trying to shell us from the position, and we were supporting a 20-pounder battery always referred to by the men as the "black-gun" battery (probably Welker's of the 1st Missouri). Its manipulation and manoeuvring were truly marvelous, and brought forth time and again cheers that sounded above the roar of battle. As a battery or deployed by platoons, section, or pieces, it would deliver fire; and the limbers, drawn by eight strong horses, would seem to bound to the rear, cannoneers spring to their places, and fly away at breakneck speed, regardless of trees, logs, or other obstacles, to a new position. Hardly would they leave the firing point, when a grist of shot or shell would come screaming through the air to find them gone. These projectiles usually went high, playing havoc with limbs and tree-tops that showered upon us, once completely enveloping a number of men, who crawled from under amidst the laughter of all near. I saw one of the enemy's guns end-up and keel-over and other confusion caused by our guns. Meanwhile we had changed position several times, and the enemy unseen, had massed an enormous force close by. We occupied for a time a sunken road that traversed a ridge, but finally moved straight to the front in line, the centre in a dim road, Major Powell commanding, in advance of the colors but walking backwards. We were soon upon the enemy, formed in such close order as to appear simply a vast multitude. Note again no skirmishers in advance. The Major, turning to the front, saw the enemy, and realizing the critical situation, waved his sword and commanded "To the rear — march!" falling, as did also the color-bearer (Note: teenage Sergeant Mathias Euler was the color-bearer), from the volley we received. Sergeant Simmons rushed out and grabbed up the flag, and four or five of us dragged Major Powell away. A few hundred yards to the rear we put him in an ambulance. He enjoined us to return to the firing line and do our best, that every man was needed. He was shot in the side (Note: family has picture of sons later wearing Major Powell's clothing which shows large hole at right hem-line in frock so Major Powell was not buried in it) and died that night, patriotic, cool, and brave to the last."

As eastern ports were closed, he probably came into the US thru' New Orleans and proceeded to Texas c.1836 where he lived as a hunter until going with Army as (civilian) color sergeant and enlisting (by Albert Tracy of Maine) at Castle Perote, Mexico during the Mexican War.

After getting out at Rhode Island, he went up into Maine with Tracy & others, remarried, but was found in the 1850 census gold-mining in Calaveras, California; returning to Maine, Powell was commissioned a 2nd lieutenant in 1855 and headed back to Texas and Indian Territory/Oklahoma, where he conducted Indian peace treaties and oversaw the construction of what became known as Powell Road into Fort Smith, Arkansas while becoming good friends with the family of famed artist Vinnie Ream, who later sculpted the US Capitol Rotunda statue of Abraham Lincoln and much else...remaining with the Army until his death.

Evidently the most central participant in the Battle of Shiloh who was KIA and is also buried there. Officer in 1st Infantry, Regular Army of the United States, detached to 25th Missouri on 24MAR1862.

After noticing 'butternuts' watching Union parade, Major Powell was sent out by COL Everett Peabody (KIA Shiloh, but buried in family plot; Springfield, MA) both to reconnoiter the evening of 05APR1862 and to lead the morning patrol 06APR1862 as described/pictured on the Fraley Field marker where the Battle of Shiloh (Pittsburg Landing) began.

Colonel Peabody took it upon himself to issue this order, and incurred the wrath of General Prentiss for same; since both Peabody and Powell died that day, they filed no after-action reports and were basically overlooked for their acts as unsung heroes in saving the Union, which researchers and writers have brought back to light by combing official records in more recent years.

Battery James Powell (1901 - 1943), one of the four coastal artillery batteries located at Fort Worden, Washington to protect Puget Sound, was named for him.

J. E. Powell was hit eleven times through the day of 06APR1862 and finally mortally wounded while walking at head of his command in the Sunken Road...first-hand account by Charles Morton: "A few hundred yards to the rear we put him in an ambulance. He enjoined us to return to the firing line and do our best, that every man was needed. He was shot in the side and died that night, patriotic, cool, and brave to the last."

Buried at Shiloh officially "unknown," but most likely in Officers' Circle #3582 per grave notes including "said to have been a major" ~ Powell had been promoted just a couple weeks earlier and did not have the proper Major epaulet ranks to wear; last picture, here included, shows him with Captain ranks ~ learned from (then) Shiloh Park Ranger Timothy Smith on two-year mission by family to disinter the lost facts of Major Powell's life.

Brigadier General Charles Morton’s eye-witness account, given at 50th Anniversary reunion in 1912, of what happened to 25th Missouri at Shiloh:

"The colonel was Everett Peabody, a strikingly handsome man of massive build and commanding presence, a native of Massachusetts, a graduate from Harvard, and a civil engineer by profession, in which he had risen to considerable prominence.

"Our major was James E. Powell, a captain of the 1st U. S. Infantry, a modest, cool-headed, capable, brave officer, who endeared himself to the hearts of all during the few days he was with us.

"I entered the service with the company by being rated a musician, and although I was not then, and have never been since, able to torture from any instrument a musical note, I had to perform for several months the orderly duty of a musician, and thus became familiar with officers and what was transpiring at regimental headquarters. Then for some time I was in charge of collecting and distributing the mail of the regiment, and came in contact, and became pretty well acquainted, with nearly every officer and man in it. The life was new to me, and intensely interesting; the events were thrilling; I was young, and my mind was susceptible of deep and lasting impressions. Nearly every man of the original company who did not fall in battle, die of wounds or disease, or was not discharged for disability received a commission. Thus it was decimated or scattered.

"Soon after my discharge, I was practically imprisoned for four years at West Point, and then at once ordered to New Mexico, and until recent years I have served almost continuously beyond the western frontier and have had but little or no opportunity to talk over with comrades the incidents of this battle. Soon after I commenced to read the post-bellum accounts of it, I wrote out my own experience, and the incidents I recount to-night are taken from that narrative. Since then I have met my three brothers who were in the regiment and battle, and I asked each in turn to give me his version on certain points; and they differed materially in nothing that is in this paper. Now I have no axe to grind here, and I would detract not one iota from the name, fame, or laurels of any man. My experience has been that about all do their very best in battle; and I have no sympathy with fireside military critics, after the fact. I took the humble and insignificant part of a private soldier in the great battle, and am content with that honor, but I would like to see a full and correct account of it recorded in history.

"You know that it is generally understood that our Army was completely surprised, and that the advance, or 6th Division, commanded by Gen'l Benj. M. Prentiss, fled from their beds before the enemy and most of them were captured. This is entirely incorrect.

"A few years since I met Col. R. T. Van Horn, Member of the House of the last Congress, and since the war editor-in-chief of the Kansas City Journal of Commerce. I asked him why as a literary man he did not write a detailed account of the attack and battle. He said he made his report as commander of the regiment immediately after the battle, and that it was on file in Washington. In that city, later, I asked Colonel Scott, in charge of the publication of the Rebellion Records, to let me read the report. In a large hand it covered less than a sheet of paper, written in a sacked camp, when all were tired and exhausted and the numbers of killed, wounded, and missing were not accurately known, — and it gave very few details.

"The regiment was reorganized after being paroled at the siege of Lexington (Note: James Powell was not at Lexington as he was then still in the REGULAR Army of the United States…not detached to 25th Missouri until 26MAR1862), and was at Benton Barracks, near St. Louis, drilling vigorously, when the news of the fall of Forts Henry and Donelson and the battle of Pea Ridge in rapid succession reached us, creating intense enthusiasm and a burning desire on the part of all to have a hand in the work of war, so favorably begun after the long weary months of waiting — in fact, discouraging inactivity. Indeed, they were about the first substantial successes of the Union arms. None who lived at the North at the commencement of the war, surrounded by patriotic influences, can understand what the loyal people of the border slave States had to undergo and endure for their loyalty at the hands of secessionists. Our surrender at Lexington after the long and trying siege, though honorable and creditable in the eyes of the government and the people, was humiliating to the regiment itself, and it longed, not only from hatred caused by persecution, but also from a feeling of revenge, to meet the enemy in a more equal contest.

"So great joy and hilarity ran through the regiment when orders came for it to move, though the men knew not whither. March 26th it was escorted by several regiments and a band through the streets of St. Louis, and boarded the steamer Continental. At Cairo we turned up the Ohio, and all began to smell our course and probable destination. A short stop was made at Paducah and General Prentiss and staff came on board. When we turned up the Tennessee, all knew we were bound for the heart of Dixie's land, and that song, modified to more appropriate words, was a constant refrain. When the recent captured works of Fort Henry, built to bar any such invasion, hove in sight, a prolonged and general shout rent the air. We viewed with much satisfaction the Union soldiers manning the guns as we sped by, and we gave them cheer after cheer.

"On we ploughed up the beautiful river, halting briefly at Savannah, the headquarters of the assembling Army, for General Prentiss and our colonel to report to Gen. C. F. Smith, for, be it remembered, that the Council of War that placed General Grant in command was not held until April 2d, practically but three days before the battle. Eight miles above we stopped at Pittsburg Landing, just at dark, March 28th. The 29th we disembarked, and Sunday, the 30th, just one week before the battle, the regiment marched past the camps of the other troops, towards Corinth, some four miles from the Landing, and went into camp perpendicularly to the road. Within three or four days other regiments arrived, extending the line to the left, forming two brigades of the 6th Division, leaving my regiment on the right, and therefore, the first of the First Brigade. Our colonel, Peabody, commanded this brigade, and my captain, Donnelly, was detail acting assistant adjutant-general. As our first lieutenant was acting regimental quartermaster temporarily and the second lieutenant was an inexperienced boy, the Captain exercised also supervision of the company, and kept it busy in camp instruction, even giving it target practice. And, it was said, he urged that rifle-pits be made and the camp prepared for defense.

"On Wednesday the 2d, a part of the regiment was sent out one-and-a-half or two miles in the direction of Corinth, on picket duty. Keeping vigilance that night, I saw the heavens illuminated by the Confederate camp-fires. We were astounded at the proximity and apparently great numbers of the enemy. Our men, visiting the farm-houses nearby, were warned that they ran great risk of capture, that the Confederate cavalry was scouring the neighborhood. It was thought at first that this was simply said to keep them away; but they were warned at every house.

"That afternoon, Thursday, we were relieved by another detail; but the men who returned to camp on Friday after noon, reported that no detail had relieved them, and that there was no picket whatever on that road between us and the enemy. If we were not aware of the dense ignorance of all, at that time, on military matters, particularly of practical soldiering, we could attribute this neglect only to traitorous design. There was considerable cavalry in the command, why was it not screening our camp, and even feeling the enemy in his own? Simply ignorance.

"We had no generals but in rank and authority. I say this not in disparagement of any who were there, but as a fact. When they learned their business, in the only school for generals, the great practical school of war, many of them won a place among the very greatest generals the world has ever produced. The Grant and Sherman of 1864 would have relieved for utter inefficiency generals of no more skill than the Grant and Sherman at Shiloh.

"On Saturday afternoon the whole 6th Division, but the camp guard, was reviewed in a field near General Prentiss's headquarters; and the rumor, afterwards confirmed, went through the camp that night that a detachment of Confederate cavalry rode up to the edge of the field and witnessed the review. At retreat, Captain Donnelly, though adjutant of the brigade, came to the company and said that the enemy was marching on the camp in force, and was within fourteen miles; there would be a battle, and he wanted to see I Company ready. He inspected the arms, equipments, and ammunition carefully, and gave instruction and advice. We were required to lie, I will not say sleep, on our arms. Whence came this information I do not know. There was no secrecy, the whole regiment anticipated a battle. Some of the officers sat up late, and others remained up all night. Among the latter was Colonel Peabody, who communicated with General Prentiss that evening, and expressed his belief that preparations should be made for an energetic defence. So accurate was his information, or correct his conviction, that during the night he ordered the two reliefs of the brigade guard not on post to patrol the front under Major Powell, field officer of the day. This developed a force believed to be the enemy's picket. As a vigilant commander, the Colonel upon getting the information sent out three companies of the regiment under Powell: B, Captain Joseph Schmitz, and E, Captain Simon S. Evans, the two companies that stormed the hospital building at Lexington; and H, Captain Hamilton Dill, a soldier of the Mexican War. They drove in the enemy's picket, and developed his main force about one and a half miles from our camp. The Colonel then sent out a part of the 21st Missouri Infantry to reinforce Major Powell's command, and in the engagement that followed Colonel Moore lost a leg.

"At daybreak wounded were being brought into camp, and the companies were formed in their streets prepared for battle. No orders coming from division headquarters, Colonel Peabody ordered the "long roll" beaten, and the regiment formed in line. The alarm was taken up by regiment after regiment and spread throughout the Army. Shortly General Prentiss came riding rapidly down the line to our Colonel, jerked up his horse, and with great earnestness, if not great anger, exclaimed: "Colonel Peabody, I will hold you personally responsible for bringing on this engagement." The Colonel, with severe dignity and illy concealed contempt, answered in his clear, strong voice: "General Prentiss, I am personally responsible for all my official acts." This stormy interview was seen, if the words were not heard, by hundreds of men; and my brother Marcus, later a lieutenant of the regiment and captain in the 43d Missouri Infantry, was orderly for the Colonel at the time, and both heard and saw what occurred.

"Each regiment of the brigade moved at once directly to the front to support Colonel Moore and meet the enemy in advance of our camp. The line was an echelon led by my regiment, which halted between half and three quarters of a mile out, a little in rear but considerably to the right of Colonel Moore's skirmish line.

"I will digress to say that the guns of the only battery in the division had not arrived. The personnel and horses were camped on the right of the brigade. Some three-fourths of a mile to the right of this gunless battery was the left of Sherman's division, its right somewhat advanced. Opposite this interval, to the front but nearer Sherman's left, was Shiloh church, a mere log country meeting-house.

"To resume: The regiment was standing at rest. The skirmishing and the fact that the next regiment came up overlapping our left, causing some confusion, diverted attention in that direction. Looking to the front again, I saw, coming down a gentle slope within easy range the Confederates massed many lines deep. Reflect for one moment upon the profound ignorance of war, — two hostile armies hunting each other without a skirmish line or advance of any kind. Lieut. Col. R. T. Van Horn, our regimental commander, gave the commands: "Attention, battalion — ready — aim — fire!" The moving mass was decimated and staggered. Its heavy loss, its very density, prevented a vigorous reply. A heavy fire was poured upon them in their deployment. But soon our men commenced to fall thick and fast. Then we sought the shelter of the trees for we were in heavy oak timber, pretty free from under brush. This position was held until our unsupported right and left were being turned when we fell back from tree to tree to avert being enveloped. Every step was stubbornly disputed. Our men were mostly hunters who would have scorned shooting a squirrel or wild turkey but through the head, and were cool. The "Johnnies" yelled vociferously "Bull Run, Bull Run!" and our men shouted back defiance — "Why don't you come on?" Indeed the withering fire they received at first, made them chary of pressing us, and we could hear and see the efforts of their officers urging them on. These were among the first casualties on the field, and doubtlessly the wounded and many of the killed were carried off, but the number of dead found here after the battle was appalling.

"Thus we resisted the advance of the enemy until our color-line was reached. With all that was at stake before, now we had our camp to defend. Here we had had our daily dress-parades and pomp of war; now had come the circumstance. Colonel Peabody, always electrifying, was doubly so now. We were not whipped, but simply out numbered. With a look of mortified pride but great determination on his handsome face he conjured the men to hold their ground. Pointing to the words in golden letters on our flag, he cried out: "Lexington, men; Lexington; remember Lexington!" (again be reminded that James Powell was NOT at Lexington because he was then still in the Regular Army of the United States, not yet detached to the 25th Missouri).

"How long we held the enemy at bay at this line I cannot say; it is beyond the range of human skill to estimate accurately the flight of time in battle. Behind trees in the company streets, and simply tents that screened us from sight, we kept up a constant fire. The enemy could not dislodge us. He dared not charge over the comparatively open ground between us, and for the same reason, as well as because of our disorganized condition and his vastly superior numbers, we could not charge him; but we held him at musket range, and expected momentarily support. We thought we had him permanently checked and would soon drive him back. Since the battle was on, the entire Army could have assembled on our line had it followed the simple maxim of war: "In the absence of orders, march to the sound of battle." And we longed for field guns to start him back and lamented they did not come. There was a perceptible lull in the roar of musketry at the left, and my attention was diverted from the front by a rifle-ball striking a tree and filling the right side of my neck with small pieces of oak bark. Stung by the sharp pain and enthused by seeing a dun-horse battery coming from the left at full run, I exclaimed; "We will give them hell now, a battery is coming!" My brother William had hardly finished chiding me for using such language, when it whirled into battery about two hundred yards away and opened upon us with grape and canister. Horror of horrors! Even ahead of the deafening reports of the gun came a storm of missiles screaming and shrieking through the air, ripping through tents, smashing tentpoles, knocking from the trees limbs that rained upon us, tearing up the ground, and raising a blinding dust. Crash — crash — came in rapid succession the showers of iron hail. A solid shot plunged through a tree and a shell burst in a mud bake-oven and covered us with a cloud of dust and beat us with clods and splinters. We couldn't help it, we had to let go.

"Could these be the guns whose reports carried the first tidings of the battle to Grant, at the breakfast-table at Savannah, twelve miles away?

"Just in the rear of the line of field officers' tents, a knot of us made another stand. Here Colonel Peabody's horse passed us, riderless and stirrups flapping in the air. We knew our brave and noble Colonel had fallen. His body was found nearby after the battle, and subsequently it was sent to Springfield, Massachusetts. In the cemetery there, a monument, draped with his country's flag, bearing the words — "Lexington, Shiloh, 25th Mo. Vol. Inf'y" — all cut in marble, marks his grave — the grave of the hero of Shiloh, — the man whose devotion cost him his life, whose vigilance, energy, and bravery saved the Army from utter surprise and defeat and the Union cause from all the far-reaching consequences. Probably no man of our Armies, in our entire history, rendered his country at one time more valuable service, and yet, outside the few survivors of his regiment, his name is hardly known, and is unhonored and unsung.

"Here this paper should properly end, for its main object is to give some of the circumstances attending the attack and shoving back of the 6th Division. But as I desire to make a few comments on, I will not say criticise, the battle, and as my story proper is not long, I will continue to presume upon your patience.

"Our little party was soon approached by Captain Donnelly, the brigade adjutant, who demanded with some asperity to know why we had not obeyed the order to retire, directed us to do so, and pointed to the rear, towards Hurlbut's division, as where our division was forming. We had simply heard no orders. We soon came to an open field, and as both flanks had been turned, to turn to the right or left meant certain death or capture. We must cross the open ground. A few rods out, and whiz — whiz — whiz! — the bullets cut the air. Zip — zip — zip! — they ricocheted by our sides to the front. None hit me, but they excited wonderfully my power of propulsion, and I believe my fortune would be assured as a sprinter now, if I could only find some equally effective promoter of locomotion.

"Behind a high rail fence, on low ground in dense under brush, we found the remnants of the regiment and brigade assembled in line. Soon a terrific artillery duel commenced, from the enemy trying to shell us from the position, and we were supporting a 20-pounder battery always referred to by the men as the "black-gun" battery (probably Welker's of the 1st Missouri). Its manipulation and manoeuvring were truly marvelous, and brought forth time and again cheers that sounded above the roar of battle. As a battery or deployed by platoons, section, or pieces, it would deliver fire; and the limbers, drawn by eight strong horses, would seem to bound to the rear, cannoneers spring to their places, and fly away at breakneck speed, regardless of trees, logs, or other obstacles, to a new position. Hardly would they leave the firing point, when a grist of shot or shell would come screaming through the air to find them gone. These projectiles usually went high, playing havoc with limbs and tree-tops that showered upon us, once completely enveloping a number of men, who crawled from under amidst the laughter of all near. I saw one of the enemy's guns end-up and keel-over and other confusion caused by our guns. Meanwhile we had changed position several times, and the enemy unseen, had massed an enormous force close by. We occupied for a time a sunken road that traversed a ridge, but finally moved straight to the front in line, the centre in a dim road, Major Powell commanding, in advance of the colors but walking backwards. We were soon upon the enemy, formed in such close order as to appear simply a vast multitude. Note again no skirmishers in advance. The Major, turning to the front, saw the enemy, and realizing the critical situation, waved his sword and commanded "To the rear — march!" falling, as did also the color-bearer (Note: teenage Sergeant Mathias Euler was the color-bearer), from the volley we received. Sergeant Simmons rushed out and grabbed up the flag, and four or five of us dragged Major Powell away. A few hundred yards to the rear we put him in an ambulance. He enjoined us to return to the firing line and do our best, that every man was needed. He was shot in the side (Note: family has picture of sons later wearing Major Powell's clothing which shows large hole at right hem-line in frock so Major Powell was not buried in it) and died that night, patriotic, cool, and brave to the last."