Educated at St. Michael's, Bognor Regis, England. Became a Nurse, first in Bermuda and then at Tientsin, China until 1913; married 3 Jun 1913.

PHYLLIS GRAY FRERE LUEDERS

(A 1983 biography transcribed from handwritten notes by her daughter,

Gerda Lüders Zander)

"Our mother, Phyllis Gray Frere Lüders, Mutti for us, was born on a remote homestead in New Zealand a hundred years ago. She died, gallantly, this early spring, a world and an age away.

"She was the third of seven children, unliked by her tired mother. Her father was a kind, jolly and always boyishly impractical man who had brought his bride, as innocent of any workaday experience as he, to start a stud farm in the newly opened country, having wangled most of a substantial inheritance from a trustee-uncle for this purpose. The farm was lost after a while, and he became a minister and missionary. (His credentials aren't clear – he had been educated at the Westminster Choir School in London; the appointment must have been made through family connections.) He liked the work, riding long circuits in the back country from a series of small parishes on the west. My mother's mother, the youngest daughter of an Anglican colonial bishop, had been brought up to see the accomplishments of leisure; now she was taken over by farm and household chores and one baby after another. She brought them to healthy and handsome growth, and all, mostly boys, able to cook and do mending. Later she had time to paint flowers again – she could bring them to life, swaying in the breeze – and spoil her youngest son.

"The children grew up free in the open, empty country, on their resourceful own except for guerrilla periods with tutors, until each in turn was shipped home to England and school at about twelve. Mutti made the months-long voyage, partly by sail and partly by steam, across the Pacific, around Cape Horn and north over the Atlantic in charge of a friendly family, though the captain had several times to speak to her about the brig after she'd been seen high in the rigging or on scaffolding over the side. At Southhampton she was met by aunts unused to dealing with a young hoyden ["A high-spirited, boisterous girl"], awkward in their daughters' passed-down clothes, but my mother wasn't used to gentleness.

"She liked her school years – sports and arts and crafts (her favorite was carpentry) and not much general information. Her parents came home when she was about sixteen, and the growing children spent holidays together again though her oldest brother had left for the army. Mutti went, after some tricks as a kindergarten teacher, to St. Bartholomew's Hospital in London as an apprentice nurse. Even in her last years, when her memory had lost details, she knew her old order there: the duty roster, the number of beds in her charge in given wards, the nature of patients and how favorably most would react, the exceptions; and she could still see herself to wake at any hour, ready for duty. In time she was sent out on her own to cases in the slums of darkest London, mostly deliveries of babies whose layettes were newspapers and whose cradles were boxes. Much later she and my father found that at about this time they had stood a few street corners apart, watching Queen Victoria's funeral pass by.

"Now her father, who had been called to Syria, asked her to come out to care for her mother, who was blinded and dying of diabetes. My mother nursed her until she died, and stayed long enough to see her father marry again, unhappily.

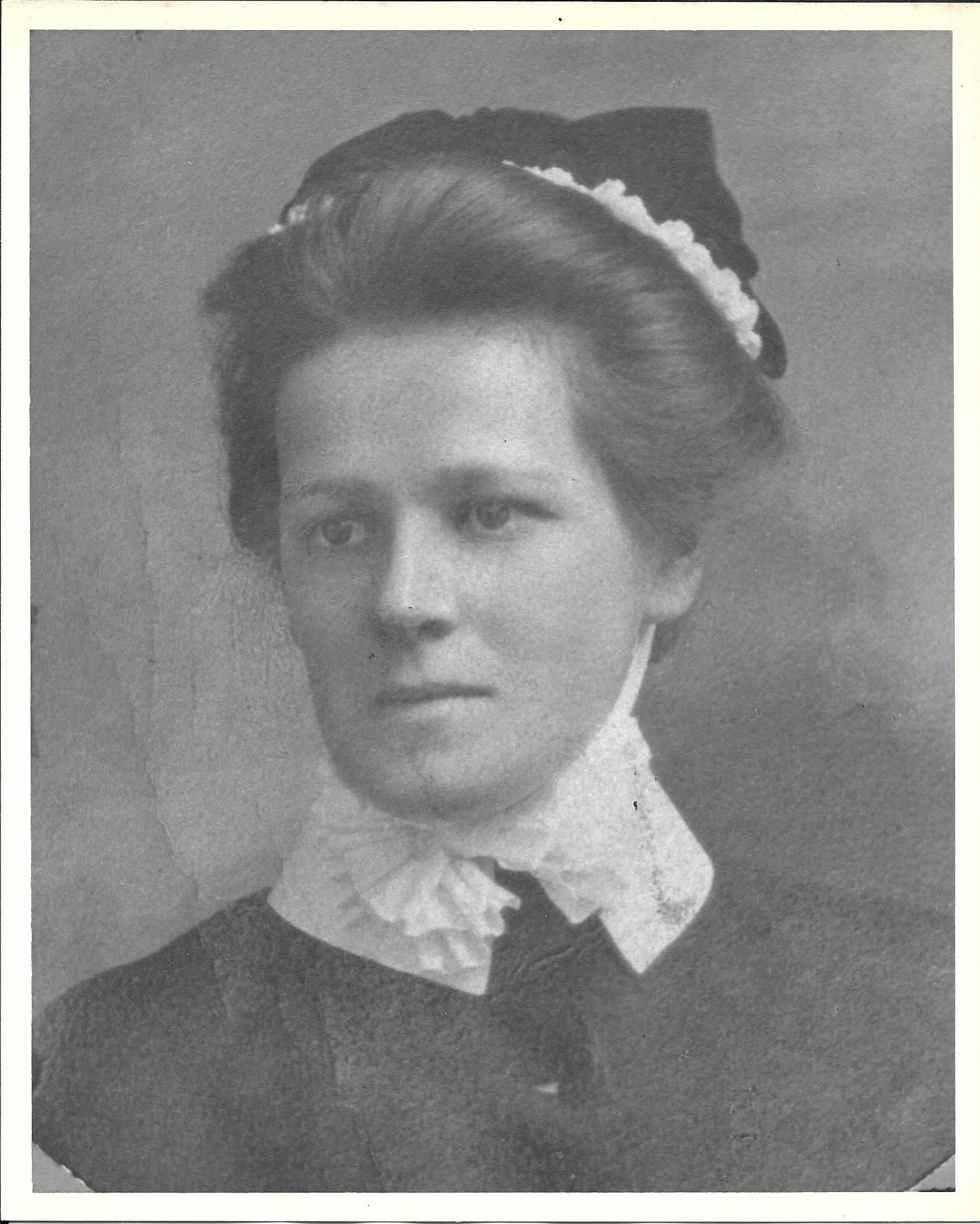

"We have a photograph of my mother then, of her serious, steadfast young face. She was never aware of it, but she was a quiet classic beauty whose lines were never emphasized by grooming; indeed, she folded her hair back in essentially the same way all her life, from chestnut through brown to white. There was always a sort of freshness and a gentle strength about her, though she could be memorably stern.

"After her father's marriage the divided family went back to England, and Mutti, wanting to see the world, found a place as head nurse (in fact the only trained nurse, and often doctor) on a primitive island near Bermuda. She was to run a small hospital, train nurses and visit outpatients; someone from a British army post nearby would visit once a week to see things were in order. This wasn't seeing the world, and after having been a little tempted by work with a missionary group in India she joined a hospital in Tientsin [now Tianjin], in northern China.

"China at that time – or rather what counted, its Foreign Concessions – was very much a colonial society of W.S. Maugham's sort, largely made up of agents of trading concerns, some consular officials, missionaries and people who had found it better to leave home. Standards were easy going if one wanted them so, and there were many takers. (I'm still uneasy about speaking this lightly of my impressive elders, though I'm so much older than they now.) My mother seems to have taken all this in with an observant clear eye, much as she had the medical practices of her Bermudans.

"She had worked in the small hospital for foreigners a few years, on the edge of social life, when an American acquaintance (whose Sunday School we children years later should have appreciated more) asked her to a picnic, a device for having her meet our father. He had had Mutti under observation, walking her dog in the early mornings near the racecourse when he was walking his dog, and wanted a formal introduction. The picnic having gone well their hosts, who liked the project, disappeared from the grove, leaving our parents to walk back to town.

"My father was a very presentable person, liked by and liking society; privately he was a man of steady seriousness and deep attachments. He was a Hanoverian German who had been in China about ten years, had done his stint upcountry, and now ran the [__?] China branch of a British export firm. He had been married and lost his wife, who left him a small daughter [Erna]. My mother and he were about the same age but otherwise very different: she was incurably an English country girl and he was cosmopolitan; she set to work to learn German from an ungifted teacher at the consulate while he had a gift for languages ancient and modern, in the case of Chinese covering the delicacies of dialect; she was innocently tone deaf, he came from a family of musicians who could whistle an aria after a first hearing. She became probably the mainstay of his life.

"They were married in time for a year's sabbatical leave – with honeymoon home with their little daughter, sightseeing over America to England and Germany, then over Siberia to a summer of warm welcome before [World] war broke in 1914. When the news came over the wires society fragmented. In the offices men dealt with practical matters of change and adjustment, lost and new opportunities, whatever their anxieties; but in the ladies' cultural world a number of Britennies and Germanies stood revealed. My mother was surprised to find she was a Hun and ostracized accordingly – indeed, jostled off the sidewalk – without being fully accepted by the other lady Huns. It was a virulent war among civilizations everywhere and bred more passionate coursenesses than later wars.

"My parents waited the First War years out, anxious about their families at home and uncertain of their own future. My father had bought some acres of land between the abrupt stony hills and the sea at Peitaiho [northeast of Tientsin, China] and started building a house of his design; when relations with his British principals became embarrassing he brought the growing family to live here for long, peaceful – and even happy – months of isolation. I remember a lullaby my mother made of a few bars from "Rock of Ages", which she hummed to each of her babies in turn, sitting in the dark and lulling them to sleep. She had learnt it in the chapel of a small Cornish fishing village her father had ministered for a while, sung by congregations who came in stormy weather to pray for those in peril on the sea.

"Late in 1918 with Allied victory China ordered all Germans deported. My parents' household in Tientsin was sold at auction excepting for a suitcaseful of necessities apiece, and they were packed on a train for a Shanghai camp to await shipment to Germany. I remember the quiet, preoccupied adults in the train's small compartments and us children playing tag in the corridors, while the half-way lot, near teen-agers who were to us glamorous, held meetings on the platforms between cars, some awesomely sitting on the steps down to the earth fleeting by below.

"In Shanghai my father managed to arrange that my mother and their following of children, the youngest a very sick baby, be allowed to stay outside the camp with friendly old servants in the native quarter. She also kept with her/their livelihood, business and banking papers which were being lifted for others' use. When we did pass inspectors, going on board ship, one of us children carried these sewn up in a golliwog, a nice stuffed doll my mother had made, one of a long line going in the end to her grandchildren. The papers later saw us fed during the near starvation in Germany, and gave my father the beginnings of a new career.

"A long voyage followed in a converted freighter (packing-crate compartments in the hold), through the thirsting heat of the Indian Ocean and the Suez Canal to the northern Mediterranean for cooling, back again around Spain and up the coast to Hamburg. Mutti always remembered an incident which had touched her at Marseilles, a group of German prisoners of war working on the docks who sang to the ship as she pulled out 'in der Heimet, in der Heimet, da gibbs ein weidersehen' ['in the home, in the home, there's a reunion.']

"They came to Germany with the winter setting in, the baby still badly sick for all my mother's care, and settled near Hamburg as the best place for my father's finding work, though there was none. It was a strained, violent time of anxieties; my mother never spoke of unfriendly memories, only of fear and uncertainty, especially for my father's safety in the civilian patrols against marauders and arsonists. For a bleak long season there seemed nothing to build on in their talks of ways and means, and in the end they agreed that my father should go back to China, clandestinely, Germans being barred, to try making a fresh start. (His old comprador [a Chinese agent engaged by a foreign establishment in China to have charge of its Chinese employees and to act as an intermediary in business affairs] met him at the station in Tientsin, without any possible fore-warning.)

"My mother stayed on alone with her crowd of children and her weak, imperfect German [language skills] until a brother and his wife offered them shelter in England. She rested there for a good part of a year until she could at last bundle everyone up for what was now going back home to China.

"I should say somewhere that this account leaves out happenings – bitter hurt – my mother would want left out. She never seemed to consider them as such, and I only heard of them tangentially. Both my mother and my father were extra-ordinarily tolerant and forgiving people.

"My father met her and the children on the way back at Singapore for escort to Tientsin. He had furnished a house in readiness and gotten some of their old staff back, who must have made life a good deal calmer for the larger family. The house at Peitaiho was reclaimed from squatters; there was not the endless pleasure of digging and planting and nurturing of the grounds, working alongside the cookies, and unheard-of mode. Life went back to its old friendly rounds.

"There were echoes of the war: free lancing Chinese soldiers at ease about Peitaiho, troops which suddenly came marching down a street in Tientsin. We could hear them coming one birthday party, when we were told to crouch away from the windows and make no sound, and my mother, agonized, was counselled by the head boy not to run out to the baby carriage in the garden. The Chinese government couldn't keep order in the countryside, and the Japanese waited a few hundred miles to the north. Still, the senior children went off to school. But schooling beyond the elementary skills was poor for the eldest, and social life indigestibly rich, so that older children were sent away for an education, unhappily often for long terms in Europe. Life in China was no longer as satisfactory.

"So few people have the means or can bring themselves to get out while the getting's possible. My father had a offer from his old firm, of second place in their New York office, with the thought of becoming first. It was not an entirely likeable opportunity as a part of the contract was monitoring #1 for suspected fraud, but that was less important than the happiness of the opening. My mother told us a great surprise was coming, as big as half the world.

"Each generation likes to tell amused stories on its predecessors, and I have no business doing so – but there's a charming picture of my mother teaching us democracy in preparation for our new life. (She hadn't much of a conception of Democracy itself, as she had never seen a difference in humans excepting what circumstance had made, and she had no interest in politics.) So we were dressed in American-style sunsuits, a relief after our usual covering but a little embarrassing, and sent out to play with the gardener's children. Neither set of children had heard of such a thing before, we didn't have Chinese and they didn't have Pidgin English, there was no bridge and it was a puzzled, shy failure.

"My parents and their large family – ages 15 to 2 – came to New York in a brilliant, breezy autumn, happy and optimistic and full of faith in this land of ideals. They settled in Staten Island, a suburb from which my father could take a ferry across the bay almost to his office door, and took out citizenship papers as soon as they could, though my mother joined the Daughters of the British Empire and my father the German Club, each going socially to the other's affairs. They would be proper immigrants.

"The children who were old enough entered the public school system my parents had heard much of; and this led to a first disappointment. The schoolgoers came down with scarlet fever and my mother, going to get employment for us while the fever worked its worrying way though the ranks, was deeply upset by the school's slovenly ways. (Our house was on a fairly elegant hill overlooking its very inelegant school district.) After this my parents kept themselves poor with tuition fees.

"It was becoming clear in my father's business that there was fraud, but also that the proceeds were being invested in a group of gangsters. These brought deportation proceedings against him, and he was warned by friendly people at the office that he was in danger from them. My mother lived in fear of what they might do. We children didn't know about this at the time, and I don't even know how it was resolved; the people at the office helped my father at some risk, and may have been decisive.

"My mother was cooking in the kitchen one day – she hadn't had practice since she'd married – when all of us but our youngest sister and brother were at school. He [Peter] was playing on the kitchen floor, and crawling, tumbled down the steep cellar steps into the boiling water of a washing machine. He lived for two days, my mother allowed to sit by him all the time. He had been our dear.

"A little later we moved to New Jersey and the eldest went off to college. The family was beginning to separate into its parts, but my parents shortly built a house outside of town with a room for every member, and, blessedly, a garden. My mother was losing her sight to cataracts, and this came so without remark from her that we didn't notice; but she couldn't drive and the move isolated her, still more so as my father was away from early morning until evening for the long journey to New York and back. But they had a garden and fields they could encroach on about, and woods behind, and they were happy with it.

"They stayed there for fifteen years, the longest my mother had ever lived in one place, through the bleak Depression and the endless troublings of growing children and the outbreak of another war. The children went off on their own, beyond easy visiting, and the house became lonely and too large. They sold it and moved into an apartment, and I thing missed it the rest of their lives – a contented place, sheltering against all weather. But it gave them the means to buy a summer home in the [Catskill] mountains, part of a [Elka Park*] club community they had been visiting with great liking for years. This was their second Peitaiho, and the first indulgence of themselves since the first one. It had a large garden, woods, and a brook they named after their first granddaughter, and good friends nearby. They spent twenty golden summers here, stretching the season from frost to frost.

"This account becomes shorter now, like time as we grow old, with few major changes excepting in oneself to mark it. The winters became grayer, with moves though several apartments, all pleasant but not their own, and not with gardens. My father's health was going. There was one long stay in a specializing hospital in New York to which my mother made the long trip every morning before six to stay until after dark. Fear become a present part of her life: she did everything she could think of, reasonable and unreasonable, to keep her companion, always losing. My father died at their house in the [Catskill] mountains one summer. He has his grave on a hillside nearby, where my mother rests too now, and where her son brought her smallest child's grave.

"She was left spent and lonely after his death in spite of all her children. A daughter [Ingeborg] bought a house with a large unkempt inviting garden and took Mutti home; when she had to go overseas for a number of years another daughter with her children came to stand by her. My mother took joy in making a garden and keeping the house, struggling with the yard man, the plumber, the electrician and the rest, wanting to help her competent daughters.

"She lived for another twenty years, although I think time fore-shortened for her. They built her a small annex of her own in the garden, and life should have been serene and happy, if it can be for an active spirit whose work is done. That was the trouble: she needed a share in active life, to do her part, but there was none, and no one who needed her care. Her children were no longer such; her grandchildren, important to her strong affections, were growing up at a time when it was most difficult to make the passage, and she accepted their problems wisely for all her anxiety, but she couldn't help. She loved the large garden, but couldn't work in it as she used to. She wanted to help in the house but there was less and less she could do, and the good manager became a dependent. She was increasingly lamed by arthritis, until she became a little bowed, hobbling figure with fingers too painfully stiff and cold for the handiwork she liked. (She taught me such a craft as a last gift.) Deafness set in, so that she was shut off from the life about her, although she was the heart of the family, and this emphasized her loneliness. The people who thought and spoke as she did were all gone.

"Phyllis means "a Green Bough", but she was an ancient tree now, the last of its stand. In the days when she was dying I once tried to tell her how much all of us loved and appreciated her, and she brushed it away – she had all her life lived in obedience not to what others thought but to what she should be. She was constant in her pilgrimage home, beyond the horizon of death.

"She died a little after dawn, and indeed, the green bough belonged out of ther chamer and into the spring.

"This seems like such a short account of a long and gallant life. It's an outline which has tried to show her unchanging steadfastness, her simple graciousness and her sweet freshness, and respect her deep feelings and reticences. May it please her."

* = El Ka is the German sounding of L K, the initials of the Liederkrantz Club centered in NY. Liederkrantz = 'songs-coronet', singing (and drinking) being original central activities of the social organization.

Educated at St. Michael's, Bognor Regis, England. Became a Nurse, first in Bermuda and then at Tientsin, China until 1913; married 3 Jun 1913.

PHYLLIS GRAY FRERE LUEDERS

(A 1983 biography transcribed from handwritten notes by her daughter,

Gerda Lüders Zander)

"Our mother, Phyllis Gray Frere Lüders, Mutti for us, was born on a remote homestead in New Zealand a hundred years ago. She died, gallantly, this early spring, a world and an age away.

"She was the third of seven children, unliked by her tired mother. Her father was a kind, jolly and always boyishly impractical man who had brought his bride, as innocent of any workaday experience as he, to start a stud farm in the newly opened country, having wangled most of a substantial inheritance from a trustee-uncle for this purpose. The farm was lost after a while, and he became a minister and missionary. (His credentials aren't clear – he had been educated at the Westminster Choir School in London; the appointment must have been made through family connections.) He liked the work, riding long circuits in the back country from a series of small parishes on the west. My mother's mother, the youngest daughter of an Anglican colonial bishop, had been brought up to see the accomplishments of leisure; now she was taken over by farm and household chores and one baby after another. She brought them to healthy and handsome growth, and all, mostly boys, able to cook and do mending. Later she had time to paint flowers again – she could bring them to life, swaying in the breeze – and spoil her youngest son.

"The children grew up free in the open, empty country, on their resourceful own except for guerrilla periods with tutors, until each in turn was shipped home to England and school at about twelve. Mutti made the months-long voyage, partly by sail and partly by steam, across the Pacific, around Cape Horn and north over the Atlantic in charge of a friendly family, though the captain had several times to speak to her about the brig after she'd been seen high in the rigging or on scaffolding over the side. At Southhampton she was met by aunts unused to dealing with a young hoyden ["A high-spirited, boisterous girl"], awkward in their daughters' passed-down clothes, but my mother wasn't used to gentleness.

"She liked her school years – sports and arts and crafts (her favorite was carpentry) and not much general information. Her parents came home when she was about sixteen, and the growing children spent holidays together again though her oldest brother had left for the army. Mutti went, after some tricks as a kindergarten teacher, to St. Bartholomew's Hospital in London as an apprentice nurse. Even in her last years, when her memory had lost details, she knew her old order there: the duty roster, the number of beds in her charge in given wards, the nature of patients and how favorably most would react, the exceptions; and she could still see herself to wake at any hour, ready for duty. In time she was sent out on her own to cases in the slums of darkest London, mostly deliveries of babies whose layettes were newspapers and whose cradles were boxes. Much later she and my father found that at about this time they had stood a few street corners apart, watching Queen Victoria's funeral pass by.

"Now her father, who had been called to Syria, asked her to come out to care for her mother, who was blinded and dying of diabetes. My mother nursed her until she died, and stayed long enough to see her father marry again, unhappily.

"We have a photograph of my mother then, of her serious, steadfast young face. She was never aware of it, but she was a quiet classic beauty whose lines were never emphasized by grooming; indeed, she folded her hair back in essentially the same way all her life, from chestnut through brown to white. There was always a sort of freshness and a gentle strength about her, though she could be memorably stern.

"After her father's marriage the divided family went back to England, and Mutti, wanting to see the world, found a place as head nurse (in fact the only trained nurse, and often doctor) on a primitive island near Bermuda. She was to run a small hospital, train nurses and visit outpatients; someone from a British army post nearby would visit once a week to see things were in order. This wasn't seeing the world, and after having been a little tempted by work with a missionary group in India she joined a hospital in Tientsin [now Tianjin], in northern China.

"China at that time – or rather what counted, its Foreign Concessions – was very much a colonial society of W.S. Maugham's sort, largely made up of agents of trading concerns, some consular officials, missionaries and people who had found it better to leave home. Standards were easy going if one wanted them so, and there were many takers. (I'm still uneasy about speaking this lightly of my impressive elders, though I'm so much older than they now.) My mother seems to have taken all this in with an observant clear eye, much as she had the medical practices of her Bermudans.

"She had worked in the small hospital for foreigners a few years, on the edge of social life, when an American acquaintance (whose Sunday School we children years later should have appreciated more) asked her to a picnic, a device for having her meet our father. He had had Mutti under observation, walking her dog in the early mornings near the racecourse when he was walking his dog, and wanted a formal introduction. The picnic having gone well their hosts, who liked the project, disappeared from the grove, leaving our parents to walk back to town.

"My father was a very presentable person, liked by and liking society; privately he was a man of steady seriousness and deep attachments. He was a Hanoverian German who had been in China about ten years, had done his stint upcountry, and now ran the [__?] China branch of a British export firm. He had been married and lost his wife, who left him a small daughter [Erna]. My mother and he were about the same age but otherwise very different: she was incurably an English country girl and he was cosmopolitan; she set to work to learn German from an ungifted teacher at the consulate while he had a gift for languages ancient and modern, in the case of Chinese covering the delicacies of dialect; she was innocently tone deaf, he came from a family of musicians who could whistle an aria after a first hearing. She became probably the mainstay of his life.

"They were married in time for a year's sabbatical leave – with honeymoon home with their little daughter, sightseeing over America to England and Germany, then over Siberia to a summer of warm welcome before [World] war broke in 1914. When the news came over the wires society fragmented. In the offices men dealt with practical matters of change and adjustment, lost and new opportunities, whatever their anxieties; but in the ladies' cultural world a number of Britennies and Germanies stood revealed. My mother was surprised to find she was a Hun and ostracized accordingly – indeed, jostled off the sidewalk – without being fully accepted by the other lady Huns. It was a virulent war among civilizations everywhere and bred more passionate coursenesses than later wars.

"My parents waited the First War years out, anxious about their families at home and uncertain of their own future. My father had bought some acres of land between the abrupt stony hills and the sea at Peitaiho [northeast of Tientsin, China] and started building a house of his design; when relations with his British principals became embarrassing he brought the growing family to live here for long, peaceful – and even happy – months of isolation. I remember a lullaby my mother made of a few bars from "Rock of Ages", which she hummed to each of her babies in turn, sitting in the dark and lulling them to sleep. She had learnt it in the chapel of a small Cornish fishing village her father had ministered for a while, sung by congregations who came in stormy weather to pray for those in peril on the sea.

"Late in 1918 with Allied victory China ordered all Germans deported. My parents' household in Tientsin was sold at auction excepting for a suitcaseful of necessities apiece, and they were packed on a train for a Shanghai camp to await shipment to Germany. I remember the quiet, preoccupied adults in the train's small compartments and us children playing tag in the corridors, while the half-way lot, near teen-agers who were to us glamorous, held meetings on the platforms between cars, some awesomely sitting on the steps down to the earth fleeting by below.

"In Shanghai my father managed to arrange that my mother and their following of children, the youngest a very sick baby, be allowed to stay outside the camp with friendly old servants in the native quarter. She also kept with her/their livelihood, business and banking papers which were being lifted for others' use. When we did pass inspectors, going on board ship, one of us children carried these sewn up in a golliwog, a nice stuffed doll my mother had made, one of a long line going in the end to her grandchildren. The papers later saw us fed during the near starvation in Germany, and gave my father the beginnings of a new career.

"A long voyage followed in a converted freighter (packing-crate compartments in the hold), through the thirsting heat of the Indian Ocean and the Suez Canal to the northern Mediterranean for cooling, back again around Spain and up the coast to Hamburg. Mutti always remembered an incident which had touched her at Marseilles, a group of German prisoners of war working on the docks who sang to the ship as she pulled out 'in der Heimet, in der Heimet, da gibbs ein weidersehen' ['in the home, in the home, there's a reunion.']

"They came to Germany with the winter setting in, the baby still badly sick for all my mother's care, and settled near Hamburg as the best place for my father's finding work, though there was none. It was a strained, violent time of anxieties; my mother never spoke of unfriendly memories, only of fear and uncertainty, especially for my father's safety in the civilian patrols against marauders and arsonists. For a bleak long season there seemed nothing to build on in their talks of ways and means, and in the end they agreed that my father should go back to China, clandestinely, Germans being barred, to try making a fresh start. (His old comprador [a Chinese agent engaged by a foreign establishment in China to have charge of its Chinese employees and to act as an intermediary in business affairs] met him at the station in Tientsin, without any possible fore-warning.)

"My mother stayed on alone with her crowd of children and her weak, imperfect German [language skills] until a brother and his wife offered them shelter in England. She rested there for a good part of a year until she could at last bundle everyone up for what was now going back home to China.

"I should say somewhere that this account leaves out happenings – bitter hurt – my mother would want left out. She never seemed to consider them as such, and I only heard of them tangentially. Both my mother and my father were extra-ordinarily tolerant and forgiving people.

"My father met her and the children on the way back at Singapore for escort to Tientsin. He had furnished a house in readiness and gotten some of their old staff back, who must have made life a good deal calmer for the larger family. The house at Peitaiho was reclaimed from squatters; there was not the endless pleasure of digging and planting and nurturing of the grounds, working alongside the cookies, and unheard-of mode. Life went back to its old friendly rounds.

"There were echoes of the war: free lancing Chinese soldiers at ease about Peitaiho, troops which suddenly came marching down a street in Tientsin. We could hear them coming one birthday party, when we were told to crouch away from the windows and make no sound, and my mother, agonized, was counselled by the head boy not to run out to the baby carriage in the garden. The Chinese government couldn't keep order in the countryside, and the Japanese waited a few hundred miles to the north. Still, the senior children went off to school. But schooling beyond the elementary skills was poor for the eldest, and social life indigestibly rich, so that older children were sent away for an education, unhappily often for long terms in Europe. Life in China was no longer as satisfactory.

"So few people have the means or can bring themselves to get out while the getting's possible. My father had a offer from his old firm, of second place in their New York office, with the thought of becoming first. It was not an entirely likeable opportunity as a part of the contract was monitoring #1 for suspected fraud, but that was less important than the happiness of the opening. My mother told us a great surprise was coming, as big as half the world.

"Each generation likes to tell amused stories on its predecessors, and I have no business doing so – but there's a charming picture of my mother teaching us democracy in preparation for our new life. (She hadn't much of a conception of Democracy itself, as she had never seen a difference in humans excepting what circumstance had made, and she had no interest in politics.) So we were dressed in American-style sunsuits, a relief after our usual covering but a little embarrassing, and sent out to play with the gardener's children. Neither set of children had heard of such a thing before, we didn't have Chinese and they didn't have Pidgin English, there was no bridge and it was a puzzled, shy failure.

"My parents and their large family – ages 15 to 2 – came to New York in a brilliant, breezy autumn, happy and optimistic and full of faith in this land of ideals. They settled in Staten Island, a suburb from which my father could take a ferry across the bay almost to his office door, and took out citizenship papers as soon as they could, though my mother joined the Daughters of the British Empire and my father the German Club, each going socially to the other's affairs. They would be proper immigrants.

"The children who were old enough entered the public school system my parents had heard much of; and this led to a first disappointment. The schoolgoers came down with scarlet fever and my mother, going to get employment for us while the fever worked its worrying way though the ranks, was deeply upset by the school's slovenly ways. (Our house was on a fairly elegant hill overlooking its very inelegant school district.) After this my parents kept themselves poor with tuition fees.

"It was becoming clear in my father's business that there was fraud, but also that the proceeds were being invested in a group of gangsters. These brought deportation proceedings against him, and he was warned by friendly people at the office that he was in danger from them. My mother lived in fear of what they might do. We children didn't know about this at the time, and I don't even know how it was resolved; the people at the office helped my father at some risk, and may have been decisive.

"My mother was cooking in the kitchen one day – she hadn't had practice since she'd married – when all of us but our youngest sister and brother were at school. He [Peter] was playing on the kitchen floor, and crawling, tumbled down the steep cellar steps into the boiling water of a washing machine. He lived for two days, my mother allowed to sit by him all the time. He had been our dear.

"A little later we moved to New Jersey and the eldest went off to college. The family was beginning to separate into its parts, but my parents shortly built a house outside of town with a room for every member, and, blessedly, a garden. My mother was losing her sight to cataracts, and this came so without remark from her that we didn't notice; but she couldn't drive and the move isolated her, still more so as my father was away from early morning until evening for the long journey to New York and back. But they had a garden and fields they could encroach on about, and woods behind, and they were happy with it.

"They stayed there for fifteen years, the longest my mother had ever lived in one place, through the bleak Depression and the endless troublings of growing children and the outbreak of another war. The children went off on their own, beyond easy visiting, and the house became lonely and too large. They sold it and moved into an apartment, and I thing missed it the rest of their lives – a contented place, sheltering against all weather. But it gave them the means to buy a summer home in the [Catskill] mountains, part of a [Elka Park*] club community they had been visiting with great liking for years. This was their second Peitaiho, and the first indulgence of themselves since the first one. It had a large garden, woods, and a brook they named after their first granddaughter, and good friends nearby. They spent twenty golden summers here, stretching the season from frost to frost.

"This account becomes shorter now, like time as we grow old, with few major changes excepting in oneself to mark it. The winters became grayer, with moves though several apartments, all pleasant but not their own, and not with gardens. My father's health was going. There was one long stay in a specializing hospital in New York to which my mother made the long trip every morning before six to stay until after dark. Fear become a present part of her life: she did everything she could think of, reasonable and unreasonable, to keep her companion, always losing. My father died at their house in the [Catskill] mountains one summer. He has his grave on a hillside nearby, where my mother rests too now, and where her son brought her smallest child's grave.

"She was left spent and lonely after his death in spite of all her children. A daughter [Ingeborg] bought a house with a large unkempt inviting garden and took Mutti home; when she had to go overseas for a number of years another daughter with her children came to stand by her. My mother took joy in making a garden and keeping the house, struggling with the yard man, the plumber, the electrician and the rest, wanting to help her competent daughters.

"She lived for another twenty years, although I think time fore-shortened for her. They built her a small annex of her own in the garden, and life should have been serene and happy, if it can be for an active spirit whose work is done. That was the trouble: she needed a share in active life, to do her part, but there was none, and no one who needed her care. Her children were no longer such; her grandchildren, important to her strong affections, were growing up at a time when it was most difficult to make the passage, and she accepted their problems wisely for all her anxiety, but she couldn't help. She loved the large garden, but couldn't work in it as she used to. She wanted to help in the house but there was less and less she could do, and the good manager became a dependent. She was increasingly lamed by arthritis, until she became a little bowed, hobbling figure with fingers too painfully stiff and cold for the handiwork she liked. (She taught me such a craft as a last gift.) Deafness set in, so that she was shut off from the life about her, although she was the heart of the family, and this emphasized her loneliness. The people who thought and spoke as she did were all gone.

"Phyllis means "a Green Bough", but she was an ancient tree now, the last of its stand. In the days when she was dying I once tried to tell her how much all of us loved and appreciated her, and she brushed it away – she had all her life lived in obedience not to what others thought but to what she should be. She was constant in her pilgrimage home, beyond the horizon of death.

"She died a little after dawn, and indeed, the green bough belonged out of ther chamer and into the spring.

"This seems like such a short account of a long and gallant life. It's an outline which has tried to show her unchanging steadfastness, her simple graciousness and her sweet freshness, and respect her deep feelings and reticences. May it please her."

* = El Ka is the German sounding of L K, the initials of the Liederkrantz Club centered in NY. Liederkrantz = 'songs-coronet', singing (and drinking) being original central activities of the social organization.