1865 - 1954

Harriet Belle (Trimmer) Hess

1881 - 1951 (they had no children)

For philanthropy and civic service, it is difficult to name any early Alaska couple whose contributions met those of Luther Hess and his wife Harriet. Luther dominated in mining, but in service to Fairbanks and the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines, Harriet's contributions at least equaled those of her husband. Together they were an unbeatable team. Their backgrounds are remarkably similar. Both were raised in the mid-west and earned college degrees there. Each taught school in the Outside States. Luther stampeded to the Klondike in 1898 through Dyea; Harriet arrived in Juneau not far behind in 1902.

Luther C. Hess was born in Milton, Illinois to William and Nancy (nee Smith) Hess on December 28, 1865. The family was prosperous. Hess grew up in a seventeen room home in Milton. He attended county elementary schools, followed by one year in Perry High School, and finished his high school years at Whipple Academy. He graduated in 1891 with an A.B. from Illinois College, a Presbyterian-Congregational school in Jacksonville, Illinois. Before he graduated from college, Hess taught at the county district school in Griggsville in 1886-7 and, following his graduation from college, was assistant principal and principal of rural district Illinois schools from 1891-1893.

Hess then read law in a private law office in Pittsfield, Illinois and was admitted to practice law before the Illinois Supreme Court on May 7, 1897. Shortly afterward, the young attorney must have been infected with gold fever, as he joined the gold rush to the Klondike via the Alaska port at Dyea in 1898. Three years later on June 3, 1901 he passed the Alaska Bar, and opened an office for business in Fairbanks. The first issue of the first newspaper (Alaska Miner), published in Fairbanks in May 1903, only months after discovery of gold, includes an advertisement for Luther C. Hess as Attorney-at-Law and as Assistant U.S. District Attorney.

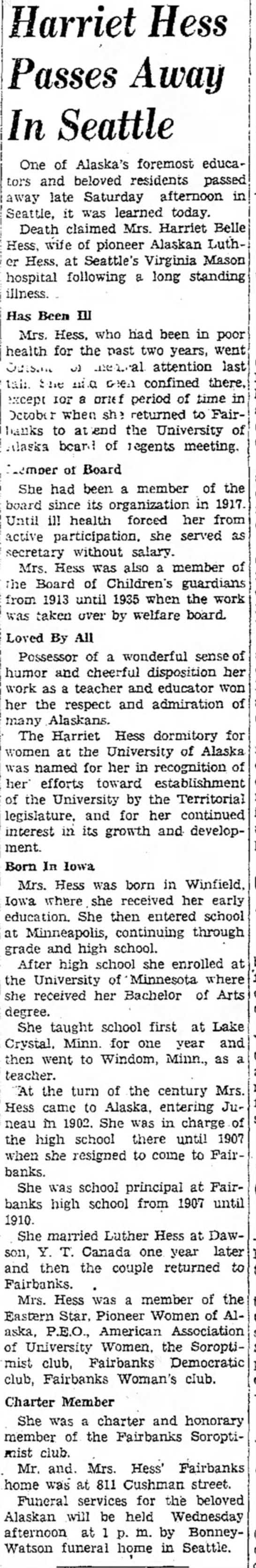

Harriet Hess was born to Isaac and Lillian (Hunt) Trimmer in Winfield, Iowa in 1881. She graduated and earned her teacher's certificate from the University of Minnesota in 1902. By the time of her graduation, she had already taught three years (1898-1900) in rural Minnesota. Something of the north must have called Harriet, as in 1902 she was in Juneau where she was high school principal from 1902-1907. Later in 1907, Harriet moved to Fairbanks into a similar position. Perhaps Harriet and Luther had met in Juneau, but surely she must have known her future husband in bustling gold rush Fairbanks. The couple was married in Dawson, Yukon Territory on September 11, 1911.

Luther Hess left the farming community of Milton, Illinois, where he had been school teacher, administrator, and a successful attorney, for the gold rush to the Klondike in 1898. In 1903 he stampeded to Fairbanks where he became one of the north's leading citizens. He was a miner, but more importantly, he invested in mines and miners. By the mid 1920s, possibly no other individual Alaskan controlled as much mining property as did Luther Hess. His legal and organizational skills were assets that aided his election and reelection to the Territorial Legislature. Hess also was a founder and long-time director and officer of the First National Bank of Fairbanks. With his wife, Harriet, Hess was a major backer of the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines, the forerunner of the University of Alaska, and of his own alma mater, Illinois College.

The law and Hess's interest and skills in debate were almost certainly, in part, a product of his heritage. Hess received a degree from Illinois College, which was the longtime home of two of the greatest American orators, Stephen A. Douglas and William Jennings Bryan. Abraham Lincoln, Douglas's protagonist , was no stranger to the Jacksonville, Illinois courthouse.

Luther was successful in mining and mining transactions and as an attorney. He returned briefly around 1905 to Milton where he shared his stories of the northland. He urged adventurous citizens of Illinois to come to the new mining camp at Fairbanks, where he perceived abundant opportunity for both mining and business ventures. One who heard Hess's message was a neighbor, Georgia Anna Eldridge. Georgia was an attractive, fun-loving, intelligent young woman from a poor family, who was looking for a good opportunity. Lael Morgan, author of Good Time Girls of the Alaska-Yukon Gold Rush, casts Luther as Georgia's tutor and backer, who urged Georgia to find out as much as she could in St. Louis about the prostitute's trade, then move to where an uneducated young woman could prosper. For Georgia Lee, the scenario may have worked. She became a successful business woman and left a $100,000 estate when she died many years later.

The story seems quite at odds with the later life of Hess, and the evidence of his involvement is only circumstantial at best. Yet like all the northern stampede towns, Fairbanks had an abundance of energetic young men with money to burn. There were saloon keepers, dance hall girls, and all-manner of unscrupulous promoters who were more than willing to help them burn it, and crime flourished. The majority of the women in the north were in the lucrative business of providing physical services for the men.

Hess was aware that in some areas the issue of prostitution was managed by authorities as a business, St. Louis, not too far from Hess's hometown, was a city that had attempted partial legalization and regulation of prostitution. At one time, St. Louis had passed a Social Evil Ordnance that segregated the prostitutes, but also gave them police protection, health examination, and free hospitalization for treatment of venereal disease. Author Morgan speculates that Hess proposed the controlled prostitution idea to Episcopal Bishop Hudson Stuck, who bought into the concept. Hess then drafted regulations for a new segregated district, where the women had a great deal of say about their own lives. As a result, crime decreased in Fairbanks and many civic leaders helped to make the program at least a short term success and Fairbanks a better place to live.

The scope of Luther's early mining ventures probably centered in the Interior near Fairbanks. A move to the Kuskokwim was the subject of a 1916 Fairbanks news article that copied a story from the Iditarod Pioneer. "Luther C. Hess, the Fairbanks banker and mining man is said to be contemplating installing a dredge on Marvel Creek [near Nyac] . . . Mr. Hess is said to have large holdings on Marvel Creek and is negotiating on other tracts." The Fairbanks paper also reported in the same year that Hess had just returned from a trip to the contiguous forty-eight states, where he was seeking funds to install a dredge on Cleary Creek at Fairbanks. The fate of the ventures is uncertain, but timing at the advent of U.S. involvement in World War I was not propitious for mining ventures. Hess had other obligations also. Hess was named Chairman of the Selective Service [draft] Board and, in 1917 he served as Speaker of the House in the Territorial Legislature. Hess than ran for the Senate. He was elected to the Territorial Senate in 1919 and 1921, and then in consecutive terms from 1929 to 1935. He was President of the Senate in 1931 and 1935.

The discovery of placer gold at Livengood north of Fairbanks in about 1916 occupied a great deal of Hess's mining efforts. A diary from 1924 kept by Hess shows meticulous record keeping about the owners of claims in the new Tolovana district. Hess owned extensive interests on Livengood Creek itself and also had claims on Amy, Gertrude, and Olive Creeks.

Hess, with scholarly and legal background, learned basic geology and prospecting in the mining short course taught creatively by Ernest Patty-- Patty had just been named Dean of the College of Agriculture and School of Mines. In the course first taught in 1925, practical prospectors mingled with financier Hess, paleontologist Otto Geist, and future mining engineers Hess used his knowledge in the acquisition of good mining claims, that were often leased out to others to operate the claims.

A lease that may have cost Hess more than he made was to a woman, Grace Lowe. Hess, leased good placer ground in Olive Creek in the Livengood district to Lowe in about 1932. Initially, Lowe seemed a good bet. She was attractive, had completed two years of college, knew bookkeeping and had a knack for operating heavy equipment. In the first years of Lowe's operation she had good press as, almost uniquely, a woman successfully operating a placer mine. But Lowe was as hard as nails and, in her later years, a perpetual litigant. In 1939, she sued Hess over the claims. Hess won.

In 1939, Hess also participated in the organization of the Alaska Miners Association (AMA). Miners were always noted for their independence, but had never organized. In the late 1930s, the U. S. Congress passed workers compensation and wage-hour legislation that applied factory type economics to almost unregulated miners. Alaskan Congressional Delegate Tony Dimond advised Alaska mining leaders that they had to get organized and send a representative to Washington to seek exceptions for their industry. Miners met in Fairbanks and organized. Two of the participant were Alaska Hall of Fame inductees Earl R. Pilgrim and Wesley Earl Dunkle. Luther Hess helped organize the meeting and was elected the first President of AMA, which, incidentally, did send a representative to Washington, D.C.

Luther and Harriet Hess were Democrats, and both very active in party affairs. Harriet was on the Democratic National Committee from 1944-1946. Both also strongly supported the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines, which became the University of Alaska in 1935. Harriet served on the Board of Regents from the foundation of the college in 1917 to her death in 1951. From 1917 until 1947 she was the unpaid secretary of the Board. She was the first woman member. Harriet continued to serve as a member of the Board until her death in 1951. Perhaps because the Hesses were childless, they were active with orphaned and abandoned children. Because of her service with the University and interest especially in women students, the woman's dorm at Fairbanks was named Harriet Hess Hall. In 1951, the dining commons at the University was dedicated to both Luther and Harriet

Harriet Hess died in 1951, Luther followed her in 1954. Much of the Hess estate went to the University. Luther, to honor his wife, established a trust fund to subsidize the residents of Harriet Hess Hall. It evidently was a matter that Luther had considered carefully. His last will states:

"It is my wish that the income be used not only for those who are needy in the usual sense of the word , but that it be used to help those who are in need of some comfort and facility that would assist them in acquiring an education."

Hess wished the funds to be distributed as unobtrusively as possible, and that the University reach out and look for incoming students who would qualify.

In addition to the University of Alaska, a Hess inheritance went to a nephew in Illinois. Luther and Harriet Hess also left bequests to Illinois College, the Pioneers of Alaska, the Fairbanks Chamber of Commerce, the Pioneers Home in Sitka, and the Boy Scouts of America.

1865 - 1954

Harriet Belle (Trimmer) Hess

1881 - 1951 (they had no children)

For philanthropy and civic service, it is difficult to name any early Alaska couple whose contributions met those of Luther Hess and his wife Harriet. Luther dominated in mining, but in service to Fairbanks and the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines, Harriet's contributions at least equaled those of her husband. Together they were an unbeatable team. Their backgrounds are remarkably similar. Both were raised in the mid-west and earned college degrees there. Each taught school in the Outside States. Luther stampeded to the Klondike in 1898 through Dyea; Harriet arrived in Juneau not far behind in 1902.

Luther C. Hess was born in Milton, Illinois to William and Nancy (nee Smith) Hess on December 28, 1865. The family was prosperous. Hess grew up in a seventeen room home in Milton. He attended county elementary schools, followed by one year in Perry High School, and finished his high school years at Whipple Academy. He graduated in 1891 with an A.B. from Illinois College, a Presbyterian-Congregational school in Jacksonville, Illinois. Before he graduated from college, Hess taught at the county district school in Griggsville in 1886-7 and, following his graduation from college, was assistant principal and principal of rural district Illinois schools from 1891-1893.

Hess then read law in a private law office in Pittsfield, Illinois and was admitted to practice law before the Illinois Supreme Court on May 7, 1897. Shortly afterward, the young attorney must have been infected with gold fever, as he joined the gold rush to the Klondike via the Alaska port at Dyea in 1898. Three years later on June 3, 1901 he passed the Alaska Bar, and opened an office for business in Fairbanks. The first issue of the first newspaper (Alaska Miner), published in Fairbanks in May 1903, only months after discovery of gold, includes an advertisement for Luther C. Hess as Attorney-at-Law and as Assistant U.S. District Attorney.

Harriet Hess was born to Isaac and Lillian (Hunt) Trimmer in Winfield, Iowa in 1881. She graduated and earned her teacher's certificate from the University of Minnesota in 1902. By the time of her graduation, she had already taught three years (1898-1900) in rural Minnesota. Something of the north must have called Harriet, as in 1902 she was in Juneau where she was high school principal from 1902-1907. Later in 1907, Harriet moved to Fairbanks into a similar position. Perhaps Harriet and Luther had met in Juneau, but surely she must have known her future husband in bustling gold rush Fairbanks. The couple was married in Dawson, Yukon Territory on September 11, 1911.

Luther Hess left the farming community of Milton, Illinois, where he had been school teacher, administrator, and a successful attorney, for the gold rush to the Klondike in 1898. In 1903 he stampeded to Fairbanks where he became one of the north's leading citizens. He was a miner, but more importantly, he invested in mines and miners. By the mid 1920s, possibly no other individual Alaskan controlled as much mining property as did Luther Hess. His legal and organizational skills were assets that aided his election and reelection to the Territorial Legislature. Hess also was a founder and long-time director and officer of the First National Bank of Fairbanks. With his wife, Harriet, Hess was a major backer of the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines, the forerunner of the University of Alaska, and of his own alma mater, Illinois College.

The law and Hess's interest and skills in debate were almost certainly, in part, a product of his heritage. Hess received a degree from Illinois College, which was the longtime home of two of the greatest American orators, Stephen A. Douglas and William Jennings Bryan. Abraham Lincoln, Douglas's protagonist , was no stranger to the Jacksonville, Illinois courthouse.

Luther was successful in mining and mining transactions and as an attorney. He returned briefly around 1905 to Milton where he shared his stories of the northland. He urged adventurous citizens of Illinois to come to the new mining camp at Fairbanks, where he perceived abundant opportunity for both mining and business ventures. One who heard Hess's message was a neighbor, Georgia Anna Eldridge. Georgia was an attractive, fun-loving, intelligent young woman from a poor family, who was looking for a good opportunity. Lael Morgan, author of Good Time Girls of the Alaska-Yukon Gold Rush, casts Luther as Georgia's tutor and backer, who urged Georgia to find out as much as she could in St. Louis about the prostitute's trade, then move to where an uneducated young woman could prosper. For Georgia Lee, the scenario may have worked. She became a successful business woman and left a $100,000 estate when she died many years later.

The story seems quite at odds with the later life of Hess, and the evidence of his involvement is only circumstantial at best. Yet like all the northern stampede towns, Fairbanks had an abundance of energetic young men with money to burn. There were saloon keepers, dance hall girls, and all-manner of unscrupulous promoters who were more than willing to help them burn it, and crime flourished. The majority of the women in the north were in the lucrative business of providing physical services for the men.

Hess was aware that in some areas the issue of prostitution was managed by authorities as a business, St. Louis, not too far from Hess's hometown, was a city that had attempted partial legalization and regulation of prostitution. At one time, St. Louis had passed a Social Evil Ordnance that segregated the prostitutes, but also gave them police protection, health examination, and free hospitalization for treatment of venereal disease. Author Morgan speculates that Hess proposed the controlled prostitution idea to Episcopal Bishop Hudson Stuck, who bought into the concept. Hess then drafted regulations for a new segregated district, where the women had a great deal of say about their own lives. As a result, crime decreased in Fairbanks and many civic leaders helped to make the program at least a short term success and Fairbanks a better place to live.

The scope of Luther's early mining ventures probably centered in the Interior near Fairbanks. A move to the Kuskokwim was the subject of a 1916 Fairbanks news article that copied a story from the Iditarod Pioneer. "Luther C. Hess, the Fairbanks banker and mining man is said to be contemplating installing a dredge on Marvel Creek [near Nyac] . . . Mr. Hess is said to have large holdings on Marvel Creek and is negotiating on other tracts." The Fairbanks paper also reported in the same year that Hess had just returned from a trip to the contiguous forty-eight states, where he was seeking funds to install a dredge on Cleary Creek at Fairbanks. The fate of the ventures is uncertain, but timing at the advent of U.S. involvement in World War I was not propitious for mining ventures. Hess had other obligations also. Hess was named Chairman of the Selective Service [draft] Board and, in 1917 he served as Speaker of the House in the Territorial Legislature. Hess than ran for the Senate. He was elected to the Territorial Senate in 1919 and 1921, and then in consecutive terms from 1929 to 1935. He was President of the Senate in 1931 and 1935.

The discovery of placer gold at Livengood north of Fairbanks in about 1916 occupied a great deal of Hess's mining efforts. A diary from 1924 kept by Hess shows meticulous record keeping about the owners of claims in the new Tolovana district. Hess owned extensive interests on Livengood Creek itself and also had claims on Amy, Gertrude, and Olive Creeks.

Hess, with scholarly and legal background, learned basic geology and prospecting in the mining short course taught creatively by Ernest Patty-- Patty had just been named Dean of the College of Agriculture and School of Mines. In the course first taught in 1925, practical prospectors mingled with financier Hess, paleontologist Otto Geist, and future mining engineers Hess used his knowledge in the acquisition of good mining claims, that were often leased out to others to operate the claims.

A lease that may have cost Hess more than he made was to a woman, Grace Lowe. Hess, leased good placer ground in Olive Creek in the Livengood district to Lowe in about 1932. Initially, Lowe seemed a good bet. She was attractive, had completed two years of college, knew bookkeeping and had a knack for operating heavy equipment. In the first years of Lowe's operation she had good press as, almost uniquely, a woman successfully operating a placer mine. But Lowe was as hard as nails and, in her later years, a perpetual litigant. In 1939, she sued Hess over the claims. Hess won.

In 1939, Hess also participated in the organization of the Alaska Miners Association (AMA). Miners were always noted for their independence, but had never organized. In the late 1930s, the U. S. Congress passed workers compensation and wage-hour legislation that applied factory type economics to almost unregulated miners. Alaskan Congressional Delegate Tony Dimond advised Alaska mining leaders that they had to get organized and send a representative to Washington to seek exceptions for their industry. Miners met in Fairbanks and organized. Two of the participant were Alaska Hall of Fame inductees Earl R. Pilgrim and Wesley Earl Dunkle. Luther Hess helped organize the meeting and was elected the first President of AMA, which, incidentally, did send a representative to Washington, D.C.

Luther and Harriet Hess were Democrats, and both very active in party affairs. Harriet was on the Democratic National Committee from 1944-1946. Both also strongly supported the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines, which became the University of Alaska in 1935. Harriet served on the Board of Regents from the foundation of the college in 1917 to her death in 1951. From 1917 until 1947 she was the unpaid secretary of the Board. She was the first woman member. Harriet continued to serve as a member of the Board until her death in 1951. Perhaps because the Hesses were childless, they were active with orphaned and abandoned children. Because of her service with the University and interest especially in women students, the woman's dorm at Fairbanks was named Harriet Hess Hall. In 1951, the dining commons at the University was dedicated to both Luther and Harriet

Harriet Hess died in 1951, Luther followed her in 1954. Much of the Hess estate went to the University. Luther, to honor his wife, established a trust fund to subsidize the residents of Harriet Hess Hall. It evidently was a matter that Luther had considered carefully. His last will states:

"It is my wish that the income be used not only for those who are needy in the usual sense of the word , but that it be used to help those who are in need of some comfort and facility that would assist them in acquiring an education."

Hess wished the funds to be distributed as unobtrusively as possible, and that the University reach out and look for incoming students who would qualify.

In addition to the University of Alaska, a Hess inheritance went to a nephew in Illinois. Luther and Harriet Hess also left bequests to Illinois College, the Pioneers of Alaska, the Fairbanks Chamber of Commerce, the Pioneers Home in Sitka, and the Boy Scouts of America.

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement