Robert E Fenton (1857-1922)

Katherine (Farr) Fenton (1859-1939)

Spouse:

Gertrude (Bauer) Fenton (1888-1982)

Children:

Dr Thomas "Terry" Fenton (1916-2006)

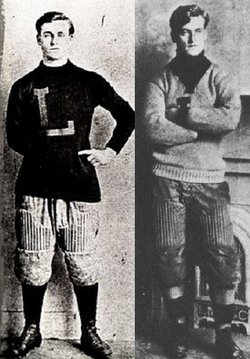

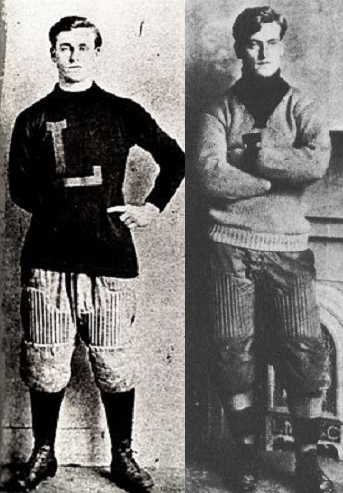

George Ellwood "Doc" Fenton was an American football player. He was elected to the LSU Hall of Fame in 1937 and to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1971.

After leaving Scranton High School, Fenton began his college football career at St. Michael's College, in Canada, in 1904. At St. Michael's, he played rugby. Fenton later talked about his time at St. Michael's by stating "I got all the fundamentals playing rugby in Toronto. I learned how to kick on the run, and I learned how to operate in an open field."[1] He later played football at Mansfield State Normal School (now Mansfield University) in Pennsylvania from 1904-1906. He started out as an end at Mansfield, but later became a star receiver in 1906, which was the first year of the legal forward pass.

Fenton was heavily recruited by LSU and Mississippi A&M (now Mississippi State University). Fenton ultimately ended up signing with LSU for the 1907 season.

George "Doc" Fenton was Louisiana's first sports legend - and that meant he had to be involved in the state's first major sports controversy.

George Elwood Fenton grew up in Pennsylvania, where his father peddled patent medicine with a traveling Indian show. That's how his athletically gifted son got the nickname "Doc".

He was an outstanding soccer player at St. Michael's College in Canada, and developed into an excellent football player at Mansfield Normal- near his hometown of Scranton, Pa. When he completed his eligibility at Mansfield, he had offers from two Southern colleges- Mississippi A&M (now Mississippi State) and Louisiana State University, which had just hired a coach from Pennsylvania named Edgar Wingard.

The primary selling point was the availability of nickel beers. Fenton wasn't happy with the blue laws in Pennsylvania, and Wingard wisely used negative recruiting to note that Starkville, Miss., also had blue laws.

Fenton, who played end at Mansfield Normal, started his LSU career at that position. But he had opportunities to run and pass in Wingard's wide-open offense, and raced 90 yards for an apparent touchdown against Louisiana Industrial Institute (later Louisiana Tech) in his first game with the Tigers. But the play was erased by a penalty.

Wingard later switched the 165-pound Fenton to quarterback, offering him a new suit of clothes as an enticement to make the switch. Using the deft footwork he had developed in soccer, the nimble Fenton was ideal for an attack that featured as many as four or five lateral passes on one play. Fenton also had a knack for kicking on the run that caused more problems for defensive units.

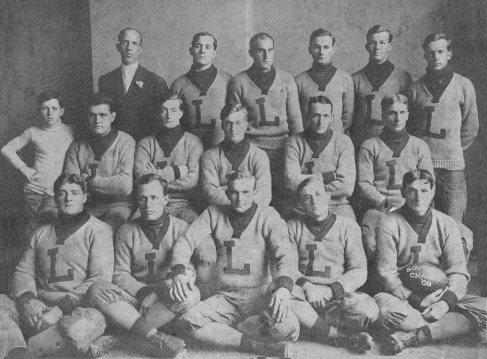

The controversy arose in the perfect 10-0 season of 1908, when a 10-2 Tiger victory over Auburn was the only game LSU didn't win by more than 20 points. The Tigers outscored their opponents 442 to 11 (LSU would've had 508 points by modern scoring rules, an average of 50.8 points per game.) The second closest game was a 22-0 shutout of Louisiana Industrial Institute in Ruston.

One reason the Auburn game was so close is that Fenton was knocked unconscious by a spectator who cracked him over the head with a cane as he was trying to get out of the end zone after scooping up a blocked punt. That is how Auburn scored its two points.

With the Tigers leading 5-2 at halftime, Wingard's wife made an inspiring talk to the players while Auburn fans pelted the tin roof of the dressing room with rocks.

"That only made us madder," Fenton recalled later.

With news of LSU's football success spreading across the country, Grantland Rice- a Vanderbilt graduate then writing for the Nashville Tennessean- wrote a story charging the Louisiana school with professionalism. Tulane also accused the Tigers of using ringers, claiming a player named Charles Ora Buser had changed his name to Bauer.

Fenton set four records in the championship season with a total of 125 points (132 with modern rules), six field goals and 36 extra points. The field goals included a 45-yarder by placement.

"Doc was the hub," recalled 175-pound tackle Marshall "Cap" Gandy, "and we were the spokes."

Following an investigation of charges against LSU by the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association, one player- Mike Lally- was ruled ineligible for the following season because he played semi-pro baseball and sang for a movie house. (Lally's eligibility was restored one year later.) Wingard resigned to return to Pennsylvania as an assistant to Glenn "Pop" Warner at the Carlisle Indian School, where Warner was developing a powerhouse built around Jim Thorpe.

Fenton had one more season at LSU, scoring 50 points to lead the 1909 Tigers to a 6-2 record. That team, coached by Vanderbilt product Joe Pritchard, concluded its season with a 12-6 upset victory over previously unbeaten Alabama. The only losses were to Arkansas and Sewanee- a school with an enrollment of only 100 students that defeated LSU en route to a perfect season in 1909.

One of the highlights of Fenton's career at LSU was the 13-player 1907 team's trip to Havana during the Christmas holidays for a Christmas Day game with Havana University. It was the first appearance of an American collegiate team on foreign soil, and with American servicemen stationed in the area following the Spanish-American was LSU had plenty of support- vocally and financially.

With the hull of the sunken battleship Maine still visible in Havana harbor, Fenton and his teammates gave the Yanks plenty to cheer about in a 54-0 romp. Cuban fans dubbed Fenton "El Rubio Vaselino"- the vaselined redhead, as elusive as the proverbial greased pig. Back in the United States, he was dubbed the "Artful Dodger."

Fenton's career records of 36 touchdowns and 269 points were intact when he died on Feb. 8, 1968. A generation later, he still holds the single season record of 125 points, set in 1908. The record for the longest field goal, shared by Fenton and H.E. Landry, was broken by Doug Moreau in 1965. The career scoring records have been broken by Charles Alexander, Dalton Hilliard, and Colt David.

More importantly, Fenton and his 1908 teammates set a perfect as the standard by which all future LSU teams would me measured. For a half-century, the greatest Tiger seasons were "1908 and next year." Since 1958, they have been "1908, 1958 and next year."

How good was Fenton? "I saw Jim Thorpe," said former LSU president Troy Middleton, "but Doc Fenton was better."

Robert E Fenton (1857-1922)

Katherine (Farr) Fenton (1859-1939)

Spouse:

Gertrude (Bauer) Fenton (1888-1982)

Children:

Dr Thomas "Terry" Fenton (1916-2006)

George Ellwood "Doc" Fenton was an American football player. He was elected to the LSU Hall of Fame in 1937 and to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1971.

After leaving Scranton High School, Fenton began his college football career at St. Michael's College, in Canada, in 1904. At St. Michael's, he played rugby. Fenton later talked about his time at St. Michael's by stating "I got all the fundamentals playing rugby in Toronto. I learned how to kick on the run, and I learned how to operate in an open field."[1] He later played football at Mansfield State Normal School (now Mansfield University) in Pennsylvania from 1904-1906. He started out as an end at Mansfield, but later became a star receiver in 1906, which was the first year of the legal forward pass.

Fenton was heavily recruited by LSU and Mississippi A&M (now Mississippi State University). Fenton ultimately ended up signing with LSU for the 1907 season.

George "Doc" Fenton was Louisiana's first sports legend - and that meant he had to be involved in the state's first major sports controversy.

George Elwood Fenton grew up in Pennsylvania, where his father peddled patent medicine with a traveling Indian show. That's how his athletically gifted son got the nickname "Doc".

He was an outstanding soccer player at St. Michael's College in Canada, and developed into an excellent football player at Mansfield Normal- near his hometown of Scranton, Pa. When he completed his eligibility at Mansfield, he had offers from two Southern colleges- Mississippi A&M (now Mississippi State) and Louisiana State University, which had just hired a coach from Pennsylvania named Edgar Wingard.

The primary selling point was the availability of nickel beers. Fenton wasn't happy with the blue laws in Pennsylvania, and Wingard wisely used negative recruiting to note that Starkville, Miss., also had blue laws.

Fenton, who played end at Mansfield Normal, started his LSU career at that position. But he had opportunities to run and pass in Wingard's wide-open offense, and raced 90 yards for an apparent touchdown against Louisiana Industrial Institute (later Louisiana Tech) in his first game with the Tigers. But the play was erased by a penalty.

Wingard later switched the 165-pound Fenton to quarterback, offering him a new suit of clothes as an enticement to make the switch. Using the deft footwork he had developed in soccer, the nimble Fenton was ideal for an attack that featured as many as four or five lateral passes on one play. Fenton also had a knack for kicking on the run that caused more problems for defensive units.

The controversy arose in the perfect 10-0 season of 1908, when a 10-2 Tiger victory over Auburn was the only game LSU didn't win by more than 20 points. The Tigers outscored their opponents 442 to 11 (LSU would've had 508 points by modern scoring rules, an average of 50.8 points per game.) The second closest game was a 22-0 shutout of Louisiana Industrial Institute in Ruston.

One reason the Auburn game was so close is that Fenton was knocked unconscious by a spectator who cracked him over the head with a cane as he was trying to get out of the end zone after scooping up a blocked punt. That is how Auburn scored its two points.

With the Tigers leading 5-2 at halftime, Wingard's wife made an inspiring talk to the players while Auburn fans pelted the tin roof of the dressing room with rocks.

"That only made us madder," Fenton recalled later.

With news of LSU's football success spreading across the country, Grantland Rice- a Vanderbilt graduate then writing for the Nashville Tennessean- wrote a story charging the Louisiana school with professionalism. Tulane also accused the Tigers of using ringers, claiming a player named Charles Ora Buser had changed his name to Bauer.

Fenton set four records in the championship season with a total of 125 points (132 with modern rules), six field goals and 36 extra points. The field goals included a 45-yarder by placement.

"Doc was the hub," recalled 175-pound tackle Marshall "Cap" Gandy, "and we were the spokes."

Following an investigation of charges against LSU by the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association, one player- Mike Lally- was ruled ineligible for the following season because he played semi-pro baseball and sang for a movie house. (Lally's eligibility was restored one year later.) Wingard resigned to return to Pennsylvania as an assistant to Glenn "Pop" Warner at the Carlisle Indian School, where Warner was developing a powerhouse built around Jim Thorpe.

Fenton had one more season at LSU, scoring 50 points to lead the 1909 Tigers to a 6-2 record. That team, coached by Vanderbilt product Joe Pritchard, concluded its season with a 12-6 upset victory over previously unbeaten Alabama. The only losses were to Arkansas and Sewanee- a school with an enrollment of only 100 students that defeated LSU en route to a perfect season in 1909.

One of the highlights of Fenton's career at LSU was the 13-player 1907 team's trip to Havana during the Christmas holidays for a Christmas Day game with Havana University. It was the first appearance of an American collegiate team on foreign soil, and with American servicemen stationed in the area following the Spanish-American was LSU had plenty of support- vocally and financially.

With the hull of the sunken battleship Maine still visible in Havana harbor, Fenton and his teammates gave the Yanks plenty to cheer about in a 54-0 romp. Cuban fans dubbed Fenton "El Rubio Vaselino"- the vaselined redhead, as elusive as the proverbial greased pig. Back in the United States, he was dubbed the "Artful Dodger."

Fenton's career records of 36 touchdowns and 269 points were intact when he died on Feb. 8, 1968. A generation later, he still holds the single season record of 125 points, set in 1908. The record for the longest field goal, shared by Fenton and H.E. Landry, was broken by Doug Moreau in 1965. The career scoring records have been broken by Charles Alexander, Dalton Hilliard, and Colt David.

More importantly, Fenton and his 1908 teammates set a perfect as the standard by which all future LSU teams would me measured. For a half-century, the greatest Tiger seasons were "1908 and next year." Since 1958, they have been "1908, 1958 and next year."

How good was Fenton? "I saw Jim Thorpe," said former LSU president Troy Middleton, "but Doc Fenton was better."

Gravesite Details

has headstone

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement