By Joyce A. Davis

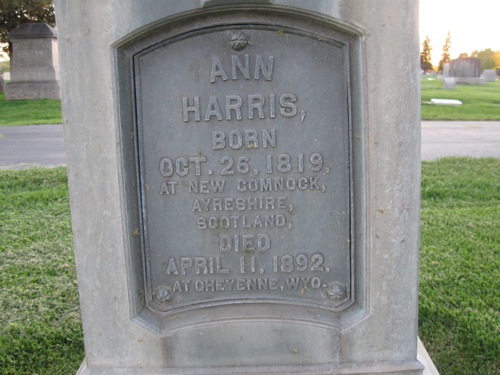

Ann Harris was born 26 October 1819, in a little mining town in Ayrshire, Scotland, known as New Comnock. Her parents were James Harris and Ann Crawford. Not much is known about her childhood. Her education probably consisted of a few months training in the elementary school combined with what training she received from her parents. It is known that she had knowledge of the scriptures, for she taught her children to love and respect the Holy Word. She was the third child in a family of twelve, nine boys and three girls.

On 24 April 1838, Ann married a young coal miner named John Hamilton. He was born 17 August 1817. They had four children, James Harris Hamilton, born 11 October 1838, Ann Hamilton, 21 November 1839. John Hamilton, 3 February 1843 and Allan Leach Hamilton 24 October 1845. Early in the year 1845, her husband John Hamilton, age 28, was killed in a coal mining accident. Following his demise the young widow returned home to her parents with her children. A few weeks later, Allan Leach was born. Soon after Ann went to work to assist the family finances, leaving the care of the children to Grandma Harris.

About 1844 the missionaries of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints began proselytizing in the Paisley area and Ann Harris Hamilton became interested in their message. At one of their meetings, Ann met a young cabinetmaker named Alexander McQueen. They were married about 1846 and joined the church. Grandmother Harris was so upset about their joining of the church that she refused to give up Allan when Ann and Alexander took the other three Hamilton children into their home. Allan was later taken to Australia by an uncle so he would be away from the Mormon Church. But that is another story.

Ann was about 25 when she married Alexander. They remained in Paisley for about fifteen years during which time seven children were born, two of whom died in infancy. During this time, Alexander was always anxious to go to Utah to join the body of the Church. In the summer of 1860 the family took passage for the states.

Their money was used up before they reached their destination and they stopped in St. Louis, Missouri to rebuild their finances and arrange for the means to reach the valley. The Civil War had started and Alexander secured work with the Federal Army building caskets for soldiers. Because he was from England he could not join the Army. Another daughter was born and the oldest daughter, Ann, of the Hamilton children was married and came to Utah and settled in Hoytsville, Utah. In 1863, the two oldest McQueen boys, Robert and John came to Utah and lived with Ann and her husband Robert Mills. Two years later the rest of the family followed and made a home in Salt Lake City.

Unable to find work when they arrived in Salt Lake, Alexander turned his skill in woodworking to a new line of art. He became a model maker for the Silver Brothers Foundry. In this occupation he would fashion out of wood the objects to be made of cast iron or bronze. He was responsible for the patterns for many pieces of ornamental ironwork that decorated the houses and public buildings in Salt Lake and Ogden. In this work he would often have problems that would tax the ingenuity of a genius. He would work over his drafting board until fatigue would overtake him. Even in his sleep he worked on the problem. Suddenly he would wake with a shout "I have it Ann, I have it!" Off to the drafting board, make a few sketches then back to bed to a sound sleep.

While working in the Army he met a man who was working on an important invention, but was unable to work out the mechanical details. Just prior to this time petroleum began to replace tallow and whale oil for illuminating purposes. Oil lamps had one serious drawback. They all smoked and stunk because the oil vaporized faster that oxygen could reach the vapor to burn it. His friend conceived the idea of burning the oil in a flat flame so that the vapor would be exposed to a greater amount of air. This would result in more complete combustion, eliminating the odor and smoke. Alexander could see the correctness of the idea and went to work to produce a suitable burner. The two men came up with the greatest improvement in home lighting since the use of candles. It was the first known flat wick oil burner. It produced a flame that was at once smokeless and odorless and much brighter than before because the flame was spread into a thin sheet instead of a round torch. Some one later put a glass windshield or chimney on it to protect it from drafts and make it burn more steadily. This was the standard lighting fixture until Edison invented the electric light. Do you wonder what Alexander realized from his invention? His friend gave him his hearty appreciation for his help. That was all.

Now he learned why he had to come to Utah. The church was building temples and needed some one who could carve the models for the iron work, especially the baptismal fonts. It was larger than any casting made up to this time in western United States. The model of the font was made up of hundreds of small pieces of wood carefully fitted and fastened with wooden dowels. After assembling the whole thing was planed and scraped to a smooth surface by hand.

The form for the oxen that uphold the font was patterned after a Scotch Ayrshire Bull. When finished, the model was covered with carving representing wavy hair as typified the Scotch cattle. The rough surface made it impractical to get the models out of the sand of the moulds. They asked Alexander to scrape them smooth, which he refused to do. He said it was not his fault that the molders could not handle the problem and he would not spoil his work. The scraping was done by another worker and the oxen were cast with smooth surfaces except for a small patch in the forehead.

Alexander was never completely happy with this work. He longed to get back to working with fine cabinet woods. The Union Pacific Railroad opened repair shops in Evanston, Wyoming and he saw a chance to satisfy this yearning. He moved his family to Evanston and worked in the car repair shop. He died in Evanston 22 September 1877 at the age of fifty-one years.

Ann never quite got over the fondness for the Hills of Bonnie Scotland. She was faithful to her espoused religion and devoted to her family. The crudeness of early pioneer life required many adjustments, but she was of sturdy stock and adapted herself to the new surroundings. She died in 1892 at the home of her youngest daughter in Cheyenne, Wyoming.

By Joyce A. Davis

Ann Harris was born 26 October 1819, in a little mining town in Ayrshire, Scotland, known as New Comnock. Her parents were James Harris and Ann Crawford. Not much is known about her childhood. Her education probably consisted of a few months training in the elementary school combined with what training she received from her parents. It is known that she had knowledge of the scriptures, for she taught her children to love and respect the Holy Word. She was the third child in a family of twelve, nine boys and three girls.

On 24 April 1838, Ann married a young coal miner named John Hamilton. He was born 17 August 1817. They had four children, James Harris Hamilton, born 11 October 1838, Ann Hamilton, 21 November 1839. John Hamilton, 3 February 1843 and Allan Leach Hamilton 24 October 1845. Early in the year 1845, her husband John Hamilton, age 28, was killed in a coal mining accident. Following his demise the young widow returned home to her parents with her children. A few weeks later, Allan Leach was born. Soon after Ann went to work to assist the family finances, leaving the care of the children to Grandma Harris.

About 1844 the missionaries of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints began proselytizing in the Paisley area and Ann Harris Hamilton became interested in their message. At one of their meetings, Ann met a young cabinetmaker named Alexander McQueen. They were married about 1846 and joined the church. Grandmother Harris was so upset about their joining of the church that she refused to give up Allan when Ann and Alexander took the other three Hamilton children into their home. Allan was later taken to Australia by an uncle so he would be away from the Mormon Church. But that is another story.

Ann was about 25 when she married Alexander. They remained in Paisley for about fifteen years during which time seven children were born, two of whom died in infancy. During this time, Alexander was always anxious to go to Utah to join the body of the Church. In the summer of 1860 the family took passage for the states.

Their money was used up before they reached their destination and they stopped in St. Louis, Missouri to rebuild their finances and arrange for the means to reach the valley. The Civil War had started and Alexander secured work with the Federal Army building caskets for soldiers. Because he was from England he could not join the Army. Another daughter was born and the oldest daughter, Ann, of the Hamilton children was married and came to Utah and settled in Hoytsville, Utah. In 1863, the two oldest McQueen boys, Robert and John came to Utah and lived with Ann and her husband Robert Mills. Two years later the rest of the family followed and made a home in Salt Lake City.

Unable to find work when they arrived in Salt Lake, Alexander turned his skill in woodworking to a new line of art. He became a model maker for the Silver Brothers Foundry. In this occupation he would fashion out of wood the objects to be made of cast iron or bronze. He was responsible for the patterns for many pieces of ornamental ironwork that decorated the houses and public buildings in Salt Lake and Ogden. In this work he would often have problems that would tax the ingenuity of a genius. He would work over his drafting board until fatigue would overtake him. Even in his sleep he worked on the problem. Suddenly he would wake with a shout "I have it Ann, I have it!" Off to the drafting board, make a few sketches then back to bed to a sound sleep.

While working in the Army he met a man who was working on an important invention, but was unable to work out the mechanical details. Just prior to this time petroleum began to replace tallow and whale oil for illuminating purposes. Oil lamps had one serious drawback. They all smoked and stunk because the oil vaporized faster that oxygen could reach the vapor to burn it. His friend conceived the idea of burning the oil in a flat flame so that the vapor would be exposed to a greater amount of air. This would result in more complete combustion, eliminating the odor and smoke. Alexander could see the correctness of the idea and went to work to produce a suitable burner. The two men came up with the greatest improvement in home lighting since the use of candles. It was the first known flat wick oil burner. It produced a flame that was at once smokeless and odorless and much brighter than before because the flame was spread into a thin sheet instead of a round torch. Some one later put a glass windshield or chimney on it to protect it from drafts and make it burn more steadily. This was the standard lighting fixture until Edison invented the electric light. Do you wonder what Alexander realized from his invention? His friend gave him his hearty appreciation for his help. That was all.

Now he learned why he had to come to Utah. The church was building temples and needed some one who could carve the models for the iron work, especially the baptismal fonts. It was larger than any casting made up to this time in western United States. The model of the font was made up of hundreds of small pieces of wood carefully fitted and fastened with wooden dowels. After assembling the whole thing was planed and scraped to a smooth surface by hand.

The form for the oxen that uphold the font was patterned after a Scotch Ayrshire Bull. When finished, the model was covered with carving representing wavy hair as typified the Scotch cattle. The rough surface made it impractical to get the models out of the sand of the moulds. They asked Alexander to scrape them smooth, which he refused to do. He said it was not his fault that the molders could not handle the problem and he would not spoil his work. The scraping was done by another worker and the oxen were cast with smooth surfaces except for a small patch in the forehead.

Alexander was never completely happy with this work. He longed to get back to working with fine cabinet woods. The Union Pacific Railroad opened repair shops in Evanston, Wyoming and he saw a chance to satisfy this yearning. He moved his family to Evanston and worked in the car repair shop. He died in Evanston 22 September 1877 at the age of fifty-one years.

Ann never quite got over the fondness for the Hills of Bonnie Scotland. She was faithful to her espoused religion and devoted to her family. The crudeness of early pioneer life required many adjustments, but she was of sturdy stock and adapted herself to the new surroundings. She died in 1892 at the home of her youngest daughter in Cheyenne, Wyoming.

Family Members

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

Advertisement