The 1910 US Census shows the family as living in Portland, Multnomah County, Oregon. The following family members are recorded as living in the home at the time of the census:

Head William C Custer M 34 Texas

Wife Annie Custer F 28 Texas

Son Joseph Custer M 10 Texas

Son Lee Custer M 8 Texas

Daug Bessie Custer F 6 Texas

Son Steve Custer M 5 Texas

Son Clide Custer M 1 Oregon

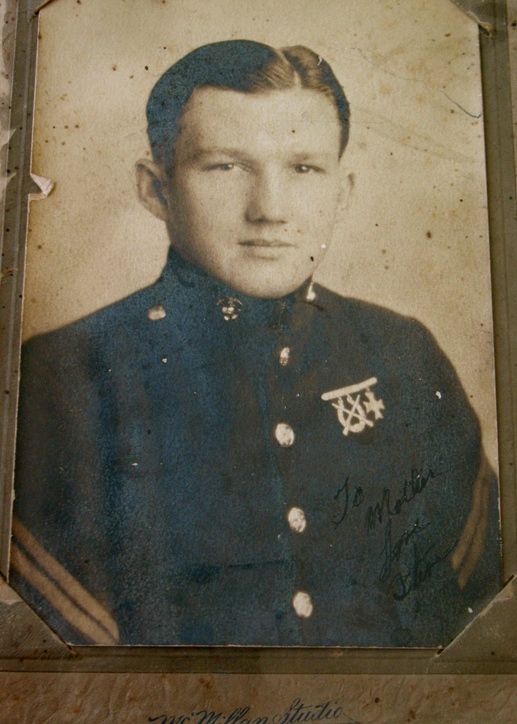

Sixteen-year-old Steven Custer decided to enlist in the Marine Corps on October 6, 1921 in San Diego, California, giving his name as Alexander S. Custer. But this was not his first tour of military duty under that name. He had joined the United States Army on March 3, 1920, and was discharged due to a reduction in force on July 30, 1921. After completing his boot camp training at Marine Corps Recruit Depot (MCRD), San Diego, he was sent to Denver, Colorado as a mail guard. He was only in Denver until January 1922 when he was transferred back to California and joined Guard Company #1 at Mare Island before settling at Puget Sound Navy Yard, Washington, in March. As a junior Marine, Private Custer was on mess duty for most of his time in Washington before joining the Marine detachment of the USS ARIZONA on June 20.

Discipline aboard the battleship was strict. For the crime of being AOL for two hours and twenty-five minutes on July 3, Custer was docked four liberties; for "leaving his post without being properly relieved" on October 3, he was fined $6.00 – a significant portion of his monthly pay. When the Marine detachment shot the rifle range for record in December, Custer was one of several who "failed to qualify." With his seagoing career off to a rocky start, Custer was relegated to the ship's laundry. This did little to improve his performance and in May 1923 he went AOL twice – the first offense alone resulted in 4 days of brig time and a $12 fine. This last brush with authority got Private Custer straightened out momentarily. He excelled at the next round of qualifications, earning a passing mark in swimming and shooting well enough to rate Expert by Army standards and Marksman by the Navy. Any good will earned by this performance was immediately dispelled in August as he went AOL yet again for several hours. He was again docked several liberties as punishment. Somehow, Custer managed a promotion to corporal in June 1924. He was spending a lot of time on the rifle range at Camp Lawton and was transferred off the ARIZONA in July.

After reenlisting on October 6, 1924, Corporal Custer took a brief furlough, then returned to duty with Guard Company #1 at Mare Island. The former "brig rat" was now an NCO trusted with escorting prisoners across state lines to the infamous Naval Prison on the island. In July 1925, Custer left the boundaries of the United States for the first time on board the US Army transport ship, USAT THOMAS. He disembarked in Guam and became the post's mail and motorcycle orderly. He served in a clerical post until leaving Guam that December.

January 1926 found Custer in Cavite, Philippine Islands, where he finally attained the difficult rating of Expert Rifleman in the Marine Corps which increased his monthly pay by $2.00. He was on duty as an instructor at the Maquinaya Rifle Range and had duty at the Naval Prison for his first six months in country – and in June he changed his name back to Steven A. Custer.

Corporal Custer sailed for China in September 1926 and served with the American Embassy in Peking as a clerk for the communications and Commander's offices until August, 1928. He then joined the renowned 84th Company, 6th Marines in Tientsin. The regiment was bound for the United States and stopped in Guam en route. Liberty was granted and somehow Custer missed the boat when it departed Guam. Having effectively marooned himself on the island, Custer was attached to the headquarters detachment and was reduced in rank to Private First Class. He remained there until December, when the USS CHAUMONT was available to transport him back to the States.

Having blown his chance with the 6th Marines, Custer was assigned to base detachments in California and then Louisiana, where he worked as a clerk. By reenlisting in the winter of 1929, Custer not only regained the second stripe of a corporal, but earned the third stripe of a sergeant – with his slip-up on Guam forgiven, he was rated with Character: Excellent. After spending the year 1930 on detached duty in Dallas, Custer was busted down to Private (for unknown reasons) and shipped over to Parris Island, where he became a clerk at the recruit depot. He gained his sergeant's rating back, lost it again, and traveled to Haiti with the First Marine Brigade as clerk to the brigade adjutant.

Custer was in Haiti and Cuba for several months. In April 1932 he was detached to compete with the Marine Corps Rifle & Pistol Team at Quantico and served as muster roll clerk to the Electoral Mission Detachment before returning to Port-au-Prince.

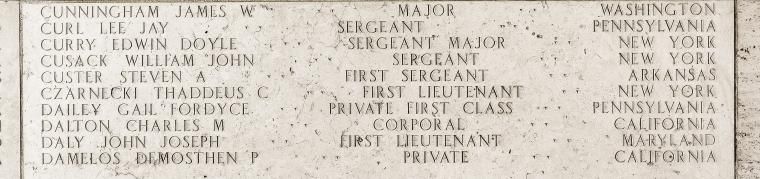

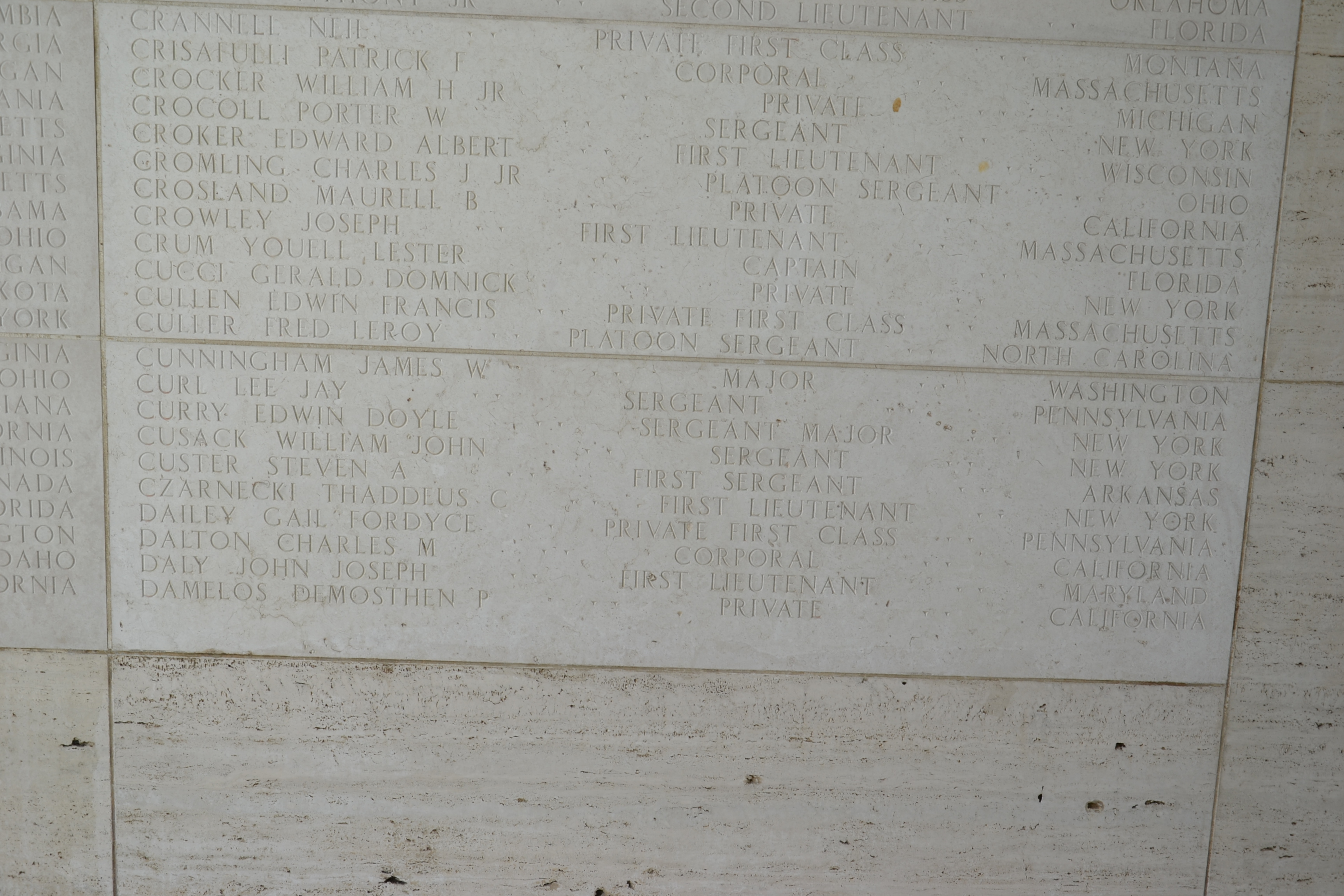

For the next several years, Custer traveled from post to post, serving as company, detachment, or base clerk from Parris Island to Company, E, Fifth Marines, rarely staying in the same place for more than a few months. At the time of his twentieth year in the Marines, 1941, Steven Custer was a sergeant on recruiting duty in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. His assignment to the 5th Marines would be his last one.

In December of 1941, Custer had new trouble but not due to anything he did. His brother, Robert Lee Custer, who had recently been granted parole from prison, stole Custer's identification and began impersonating him. But the brother died later that month.

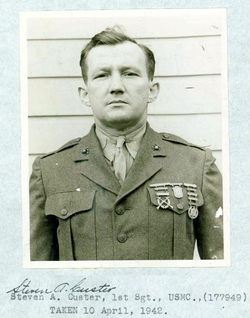

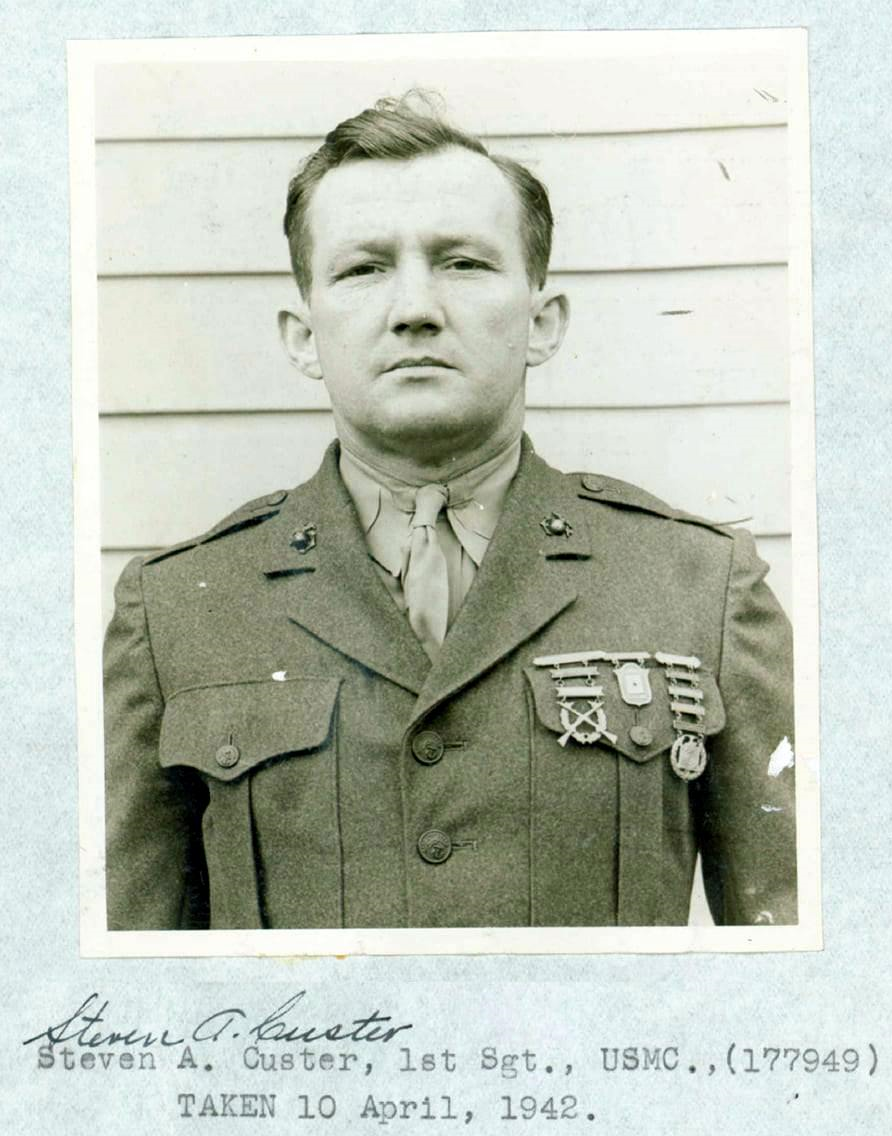

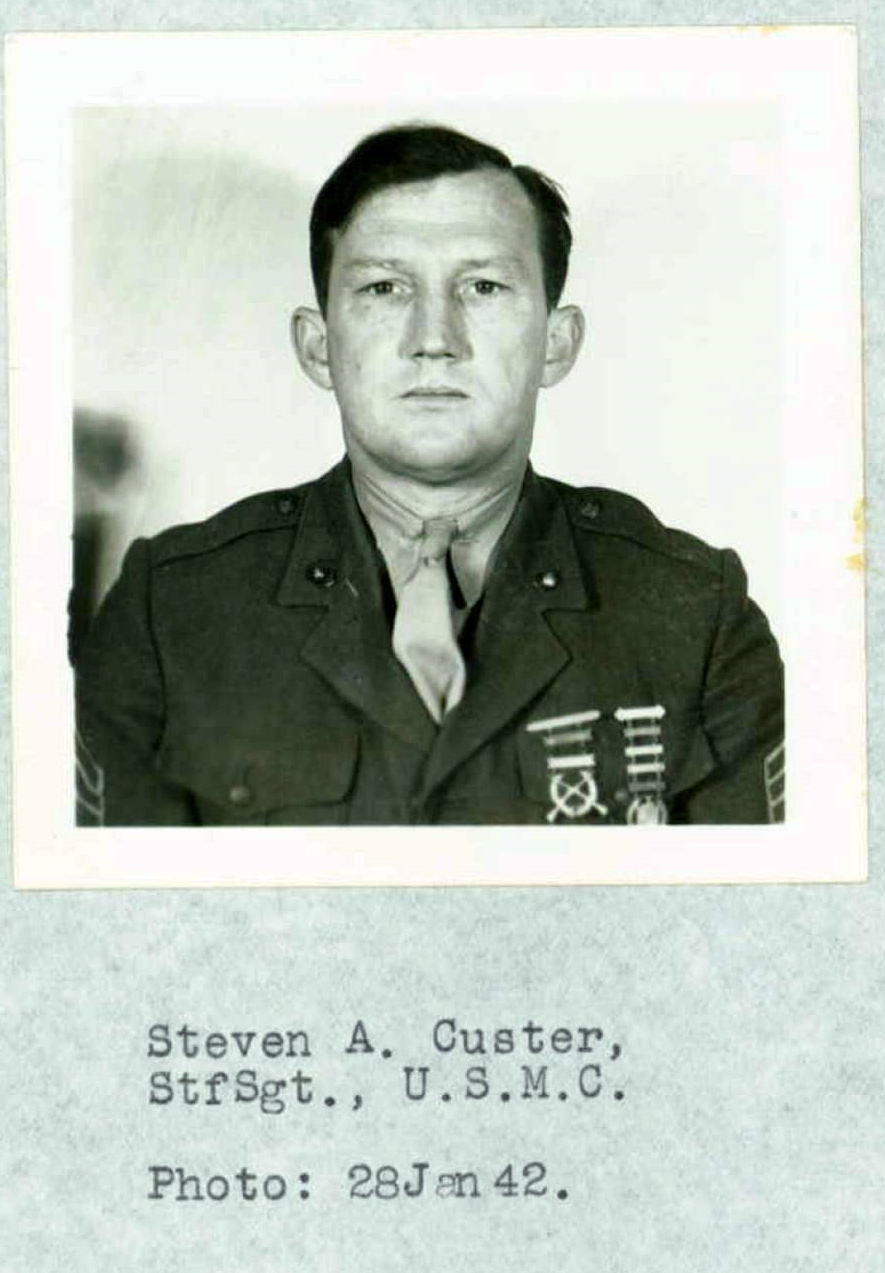

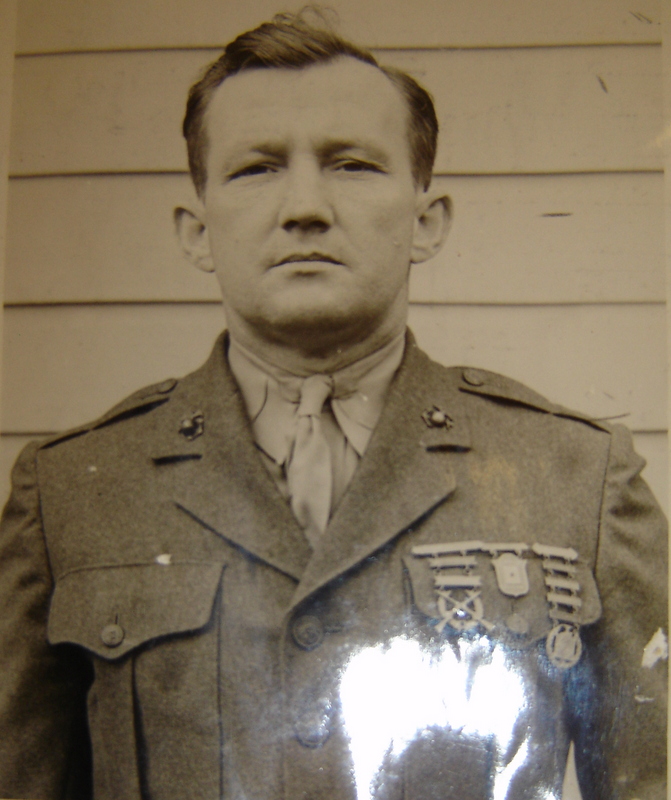

The attack on Pearl Harbor led to Custer's promotion to Staff Sergeant and assignment to Headquarters and Service Company, 5th Marine Regiment, First Marine Division. As a senior NCO in the Intelligence Section, Custer reached the rank of First Sergeant in the Spring of 1942. The 5th Marines soon deployed to Wellington, New Zealand, for further training before they took the war to the Japanese. But not long after their arrival, the training time was greatly reduced and the Regiment was prepped for an amphibious landing at a place in the Solomon Islands named Guadalcanal. The intelligence information was sparse and, as Custer and his fellow intelligence men would learn, unreliable.

The landing on Guadalcanal went unopposed. The Japanese waited in the jungle for the coming battle with the Marines. The Intelligence Section set about gathering and analyzing information they gleaned from the area. On August 12th, a Marine patrol from the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, captured a Japanese soldier named Sakado, found in their area. The Marines learned that the Japanese west of the Matanikau River were a disorganized and demoralized group, short on food and in poor health. They could, Sakado thought, be induced to surrender given the proper conditions.

The commander of the Intelligence Section, Colonel Frank Bryan Goettge, had been annoyed by the rush job that intelligence had been forced into in New Zealand and the now apparent shortcomings in maps and other data were becoming more evident. Sakado was a godsend. Col. Goettge sent Custer to organize a patrol, which Goettge himself would head. They would take an interpreter, a doctor, a good portion of the intelligence section and some riflemen for support, and boat across to a secluded beach where a white flag had reportedly been seen. They would convince the Japanese there to surrender and work their way back to Headquarters the next day, with Goettge presumably at the head of a cluster of happily surrendered Japanese.

Custer formulated a patrol and timetable for the patrol to be launched but Col. Goettge made significant changes. The reorganization took hours, causing Custer's original timetable to be thrown off. Worried about the changes and the late start, Captain Wilfred H. "Bill" Ringer, the patrol's second in command found Captain Lyman Spurlock of L/3/5 and asked if he could send a relief patrol if something went wrong. Spurlock demurred, saying "It would be difficult at night."

The patrol, consisting of 25 men plus Sakado (who was led by a rope around his neck at different times by Custer and Platoon Sergeant Caltrider) set out from the camp at Kukum at about 1800 hours – a twelve hour delay caused by the numerous personnel changes. The men were traveling light, carrying enough food for one day, a canteen, a poncho, and only light weapons (Custer had wanted heavy machine-guns but Col. Goettge denied this request).

Due to tidal issues, the delay caused another problem – it was now too late to risk heading for the original landing site. Ignoring the warnings of Lieutenant Colonel Bill Whaling and the cries of Sakado, who begged them not to land there, the boat turned for shore and landed about 200 yards west of the Matanikau. The boat ran up on a sandbar, forcing the Marines to jump over the gun-whales and rock it free, creating quite a racket. They waded in to shore and, taking cover behind a line of banyan trees, and held a quick council of war. All the noise they had made and now this pause gave the Japanese soldiers of the 2nd Platoon, 11th CU Security Force under Lt. Soichi Shindo, plenty of time to pick their targets. As Col. Goettge led an advance party into the treeline, two shots rang out. Col. Goettge fell dead with a shot to the head. Custer, who was at Gottege's side, was shot in the arm and fell seriously wounded across his Colonel's body. Two Marines who crawled forward to check on the men recovered Goettge's insignia and wristwatch. Command passed to Captain Ringer, who had dragged the mortally wounded Custer back to the perimeter as there was no cover on the beach, yelled an order to call back the boat. One of the corporals ran into the surf and fired wildly in the air at the still visible boat, but to no avail. The Marines were trapped. Soon, Captain Ringer himself was wounded. The regiment's interpreter, Lieutenant Cory, was down with an agonizing stomach wound. Regimental Surgeon Dr. Malcolm Pratt,USN, was shot while tending to a wounded man. Every few minutes, a Marine was hit. As more Marines dropped, killed or wounded, Captain Ringer called for Corporal William Bainbridge and ordered him to head back along the beach to the American perimeter to get help. Bainbridge set off at a run and disappeared into the darkness never to be seen alive again (Cpl. Bainbridge's bullet riddled body would be found by a Marine Patrol a week later, several hundred yards from where the Goettge Patrol was massacred. He was buried were he fell).

The survivors formed a defensive perimeter on the beach, and over the course of the night and following morning the Marines were gradually picked off by the Japanese defenders. By dawn, the patrol had been wiped out aside from three survivors who managed to swim back to friendly lines one at a time. They reported seeing Japanese swords "flashing in the sun" as the Japanese fell upon the wounded and dead Marines.

The bodies of the Goettge Patrol were never recovered. There were accounts of knowing where they were and that they had been thrown into fighting trenches and covered up. There were at least three reports over the following weeks after the fight that the bodies were partially buried in the sand with limbs sticking out of the makeshift graves. One report, made by a Marine years later stated he was on patrol at the scene of the slaughter and personally saw the mutilated bodies of Goettge's patrol to include decapitated torsos and boots with limbs still attached. But no bodies were ever recovered. One of those torso's, still had on it's Herringbone twill combat shirt with the rank of First Sergeant stenciled to the sleeve. It is believed, this was the remains of Steve Custer.

Custer's body as well as the remains of the rest of the men are lost to this day. Several recovery attempts over the past 65 years have found nothing and it is suspected now that building in the area and the change of the shoreline will result in the patrol's remains never being recovered.

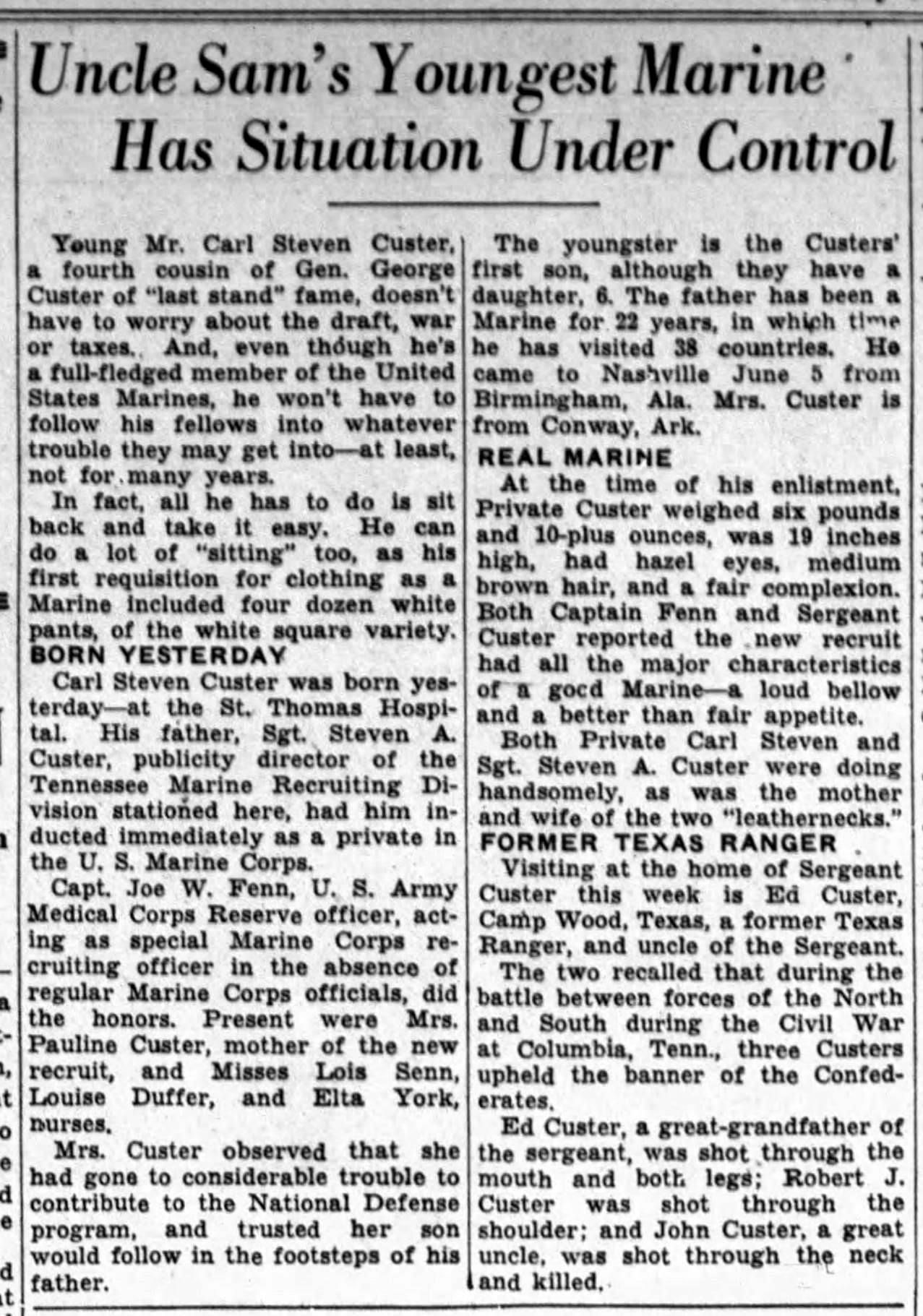

Custer was married at the time of his death. His wife, Mady Pauline Custer, had brought a daughter to the marriage, Marian Dionne, and together Custer and Mady had a son, Carl Steven Custer.

First Sergeant Steven Alexander Custer, Sn #177949, earned the following badges/decorations for his service in the United State Marine Corps and during World War II:

- Combat Action Ribbon

- Purple Heart Medal

- Marine Corps Expeditionary Medal #4220

- Marine Corps Good Conduct Medal #86671

- American Defense Service Medal

- Asiatic-Pacific Theater of Operations Campaign Medal with one bronze battle/campaign star

- World War II Victory Medal

- Navy/Marine Corps Presidential Unit Citation Ribbon

- Marine Corps Rifle Marksmanship Badge

- Marine Corps Basic Qualification Badge with Bar(s)

- Marine Corps Distinguished Marksmanship Badge

**NOTE** - A portion of this bio is based on information from the website missingmarines.com. They have done a fantastic job of researching approximately 3000 US Marines whose bodies were lost in the war. This writer wholeheartedly recommends their site for researchers or families of the missing. - Rick Lawrence, MSgt., USMC/USAFR {RET})

The 1910 US Census shows the family as living in Portland, Multnomah County, Oregon. The following family members are recorded as living in the home at the time of the census:

Head William C Custer M 34 Texas

Wife Annie Custer F 28 Texas

Son Joseph Custer M 10 Texas

Son Lee Custer M 8 Texas

Daug Bessie Custer F 6 Texas

Son Steve Custer M 5 Texas

Son Clide Custer M 1 Oregon

Sixteen-year-old Steven Custer decided to enlist in the Marine Corps on October 6, 1921 in San Diego, California, giving his name as Alexander S. Custer. But this was not his first tour of military duty under that name. He had joined the United States Army on March 3, 1920, and was discharged due to a reduction in force on July 30, 1921. After completing his boot camp training at Marine Corps Recruit Depot (MCRD), San Diego, he was sent to Denver, Colorado as a mail guard. He was only in Denver until January 1922 when he was transferred back to California and joined Guard Company #1 at Mare Island before settling at Puget Sound Navy Yard, Washington, in March. As a junior Marine, Private Custer was on mess duty for most of his time in Washington before joining the Marine detachment of the USS ARIZONA on June 20.

Discipline aboard the battleship was strict. For the crime of being AOL for two hours and twenty-five minutes on July 3, Custer was docked four liberties; for "leaving his post without being properly relieved" on October 3, he was fined $6.00 – a significant portion of his monthly pay. When the Marine detachment shot the rifle range for record in December, Custer was one of several who "failed to qualify." With his seagoing career off to a rocky start, Custer was relegated to the ship's laundry. This did little to improve his performance and in May 1923 he went AOL twice – the first offense alone resulted in 4 days of brig time and a $12 fine. This last brush with authority got Private Custer straightened out momentarily. He excelled at the next round of qualifications, earning a passing mark in swimming and shooting well enough to rate Expert by Army standards and Marksman by the Navy. Any good will earned by this performance was immediately dispelled in August as he went AOL yet again for several hours. He was again docked several liberties as punishment. Somehow, Custer managed a promotion to corporal in June 1924. He was spending a lot of time on the rifle range at Camp Lawton and was transferred off the ARIZONA in July.

After reenlisting on October 6, 1924, Corporal Custer took a brief furlough, then returned to duty with Guard Company #1 at Mare Island. The former "brig rat" was now an NCO trusted with escorting prisoners across state lines to the infamous Naval Prison on the island. In July 1925, Custer left the boundaries of the United States for the first time on board the US Army transport ship, USAT THOMAS. He disembarked in Guam and became the post's mail and motorcycle orderly. He served in a clerical post until leaving Guam that December.

January 1926 found Custer in Cavite, Philippine Islands, where he finally attained the difficult rating of Expert Rifleman in the Marine Corps which increased his monthly pay by $2.00. He was on duty as an instructor at the Maquinaya Rifle Range and had duty at the Naval Prison for his first six months in country – and in June he changed his name back to Steven A. Custer.

Corporal Custer sailed for China in September 1926 and served with the American Embassy in Peking as a clerk for the communications and Commander's offices until August, 1928. He then joined the renowned 84th Company, 6th Marines in Tientsin. The regiment was bound for the United States and stopped in Guam en route. Liberty was granted and somehow Custer missed the boat when it departed Guam. Having effectively marooned himself on the island, Custer was attached to the headquarters detachment and was reduced in rank to Private First Class. He remained there until December, when the USS CHAUMONT was available to transport him back to the States.

Having blown his chance with the 6th Marines, Custer was assigned to base detachments in California and then Louisiana, where he worked as a clerk. By reenlisting in the winter of 1929, Custer not only regained the second stripe of a corporal, but earned the third stripe of a sergeant – with his slip-up on Guam forgiven, he was rated with Character: Excellent. After spending the year 1930 on detached duty in Dallas, Custer was busted down to Private (for unknown reasons) and shipped over to Parris Island, where he became a clerk at the recruit depot. He gained his sergeant's rating back, lost it again, and traveled to Haiti with the First Marine Brigade as clerk to the brigade adjutant.

Custer was in Haiti and Cuba for several months. In April 1932 he was detached to compete with the Marine Corps Rifle & Pistol Team at Quantico and served as muster roll clerk to the Electoral Mission Detachment before returning to Port-au-Prince.

For the next several years, Custer traveled from post to post, serving as company, detachment, or base clerk from Parris Island to Company, E, Fifth Marines, rarely staying in the same place for more than a few months. At the time of his twentieth year in the Marines, 1941, Steven Custer was a sergeant on recruiting duty in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. His assignment to the 5th Marines would be his last one.

In December of 1941, Custer had new trouble but not due to anything he did. His brother, Robert Lee Custer, who had recently been granted parole from prison, stole Custer's identification and began impersonating him. But the brother died later that month.

The attack on Pearl Harbor led to Custer's promotion to Staff Sergeant and assignment to Headquarters and Service Company, 5th Marine Regiment, First Marine Division. As a senior NCO in the Intelligence Section, Custer reached the rank of First Sergeant in the Spring of 1942. The 5th Marines soon deployed to Wellington, New Zealand, for further training before they took the war to the Japanese. But not long after their arrival, the training time was greatly reduced and the Regiment was prepped for an amphibious landing at a place in the Solomon Islands named Guadalcanal. The intelligence information was sparse and, as Custer and his fellow intelligence men would learn, unreliable.

The landing on Guadalcanal went unopposed. The Japanese waited in the jungle for the coming battle with the Marines. The Intelligence Section set about gathering and analyzing information they gleaned from the area. On August 12th, a Marine patrol from the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, captured a Japanese soldier named Sakado, found in their area. The Marines learned that the Japanese west of the Matanikau River were a disorganized and demoralized group, short on food and in poor health. They could, Sakado thought, be induced to surrender given the proper conditions.

The commander of the Intelligence Section, Colonel Frank Bryan Goettge, had been annoyed by the rush job that intelligence had been forced into in New Zealand and the now apparent shortcomings in maps and other data were becoming more evident. Sakado was a godsend. Col. Goettge sent Custer to organize a patrol, which Goettge himself would head. They would take an interpreter, a doctor, a good portion of the intelligence section and some riflemen for support, and boat across to a secluded beach where a white flag had reportedly been seen. They would convince the Japanese there to surrender and work their way back to Headquarters the next day, with Goettge presumably at the head of a cluster of happily surrendered Japanese.

Custer formulated a patrol and timetable for the patrol to be launched but Col. Goettge made significant changes. The reorganization took hours, causing Custer's original timetable to be thrown off. Worried about the changes and the late start, Captain Wilfred H. "Bill" Ringer, the patrol's second in command found Captain Lyman Spurlock of L/3/5 and asked if he could send a relief patrol if something went wrong. Spurlock demurred, saying "It would be difficult at night."

The patrol, consisting of 25 men plus Sakado (who was led by a rope around his neck at different times by Custer and Platoon Sergeant Caltrider) set out from the camp at Kukum at about 1800 hours – a twelve hour delay caused by the numerous personnel changes. The men were traveling light, carrying enough food for one day, a canteen, a poncho, and only light weapons (Custer had wanted heavy machine-guns but Col. Goettge denied this request).

Due to tidal issues, the delay caused another problem – it was now too late to risk heading for the original landing site. Ignoring the warnings of Lieutenant Colonel Bill Whaling and the cries of Sakado, who begged them not to land there, the boat turned for shore and landed about 200 yards west of the Matanikau. The boat ran up on a sandbar, forcing the Marines to jump over the gun-whales and rock it free, creating quite a racket. They waded in to shore and, taking cover behind a line of banyan trees, and held a quick council of war. All the noise they had made and now this pause gave the Japanese soldiers of the 2nd Platoon, 11th CU Security Force under Lt. Soichi Shindo, plenty of time to pick their targets. As Col. Goettge led an advance party into the treeline, two shots rang out. Col. Goettge fell dead with a shot to the head. Custer, who was at Gottege's side, was shot in the arm and fell seriously wounded across his Colonel's body. Two Marines who crawled forward to check on the men recovered Goettge's insignia and wristwatch. Command passed to Captain Ringer, who had dragged the mortally wounded Custer back to the perimeter as there was no cover on the beach, yelled an order to call back the boat. One of the corporals ran into the surf and fired wildly in the air at the still visible boat, but to no avail. The Marines were trapped. Soon, Captain Ringer himself was wounded. The regiment's interpreter, Lieutenant Cory, was down with an agonizing stomach wound. Regimental Surgeon Dr. Malcolm Pratt,USN, was shot while tending to a wounded man. Every few minutes, a Marine was hit. As more Marines dropped, killed or wounded, Captain Ringer called for Corporal William Bainbridge and ordered him to head back along the beach to the American perimeter to get help. Bainbridge set off at a run and disappeared into the darkness never to be seen alive again (Cpl. Bainbridge's bullet riddled body would be found by a Marine Patrol a week later, several hundred yards from where the Goettge Patrol was massacred. He was buried were he fell).

The survivors formed a defensive perimeter on the beach, and over the course of the night and following morning the Marines were gradually picked off by the Japanese defenders. By dawn, the patrol had been wiped out aside from three survivors who managed to swim back to friendly lines one at a time. They reported seeing Japanese swords "flashing in the sun" as the Japanese fell upon the wounded and dead Marines.

The bodies of the Goettge Patrol were never recovered. There were accounts of knowing where they were and that they had been thrown into fighting trenches and covered up. There were at least three reports over the following weeks after the fight that the bodies were partially buried in the sand with limbs sticking out of the makeshift graves. One report, made by a Marine years later stated he was on patrol at the scene of the slaughter and personally saw the mutilated bodies of Goettge's patrol to include decapitated torsos and boots with limbs still attached. But no bodies were ever recovered. One of those torso's, still had on it's Herringbone twill combat shirt with the rank of First Sergeant stenciled to the sleeve. It is believed, this was the remains of Steve Custer.

Custer's body as well as the remains of the rest of the men are lost to this day. Several recovery attempts over the past 65 years have found nothing and it is suspected now that building in the area and the change of the shoreline will result in the patrol's remains never being recovered.

Custer was married at the time of his death. His wife, Mady Pauline Custer, had brought a daughter to the marriage, Marian Dionne, and together Custer and Mady had a son, Carl Steven Custer.

First Sergeant Steven Alexander Custer, Sn #177949, earned the following badges/decorations for his service in the United State Marine Corps and during World War II:

- Combat Action Ribbon

- Purple Heart Medal

- Marine Corps Expeditionary Medal #4220

- Marine Corps Good Conduct Medal #86671

- American Defense Service Medal

- Asiatic-Pacific Theater of Operations Campaign Medal with one bronze battle/campaign star

- World War II Victory Medal

- Navy/Marine Corps Presidential Unit Citation Ribbon

- Marine Corps Rifle Marksmanship Badge

- Marine Corps Basic Qualification Badge with Bar(s)

- Marine Corps Distinguished Marksmanship Badge

**NOTE** - A portion of this bio is based on information from the website missingmarines.com. They have done a fantastic job of researching approximately 3000 US Marines whose bodies were lost in the war. This writer wholeheartedly recommends their site for researchers or families of the missing. - Rick Lawrence, MSgt., USMC/USAFR {RET})

Gravesite Details

Entered the service from Arkansas.

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

Advertisement