Hans has been a hard member of the family to track for the early part of his life. From the families arrival in the US in 1843 to 1855 Hans location wasn't know for sure for a long time. Hans is not listed in the 1850 census as living with his father. It's possible that he was living in the Rochester, Racine County, Wisconsin area at the time of the 1850 Census. I've found a Hans Oleson who was listed as a laborer and attending school. This Hans Oleson was living with the Areatus Bailey family in the 1850 Federal Census for Rochester, Racine County, Wisconsin. The age and everything is right for our Hans and Rochester is only eight miles from the Evenson homestead. But I don't have any way to confirm it's him and Oleson is such a common name. In the summer of 2013 Linda Evenson, the librarian for the Freeborn Historical Society found an obituary for Ole K. Morreim that helped confirm Hans's residence for some of the missing years. According to Ole Morreim's obituary on Page 5 of the Albert Lea newspaper The Evening Tribune dated November 4th, 1915 Hans came to Minnesota with Ole and his brother Thosten in 1854. In Ole's obituary it states, "In 1854 Ole, together with his brother Thosten and Mr. Hans Olsen Kjonaas, left for Minnesota, traveling by ox team, they arrived in Goodhue Co. that fall, stayed there only a year and a half when they moved to Freeborn Co. where in the fall of 1856 they filed on claims which they have kept every since". There is a conflict with these dates and other information sources. In the 1905 Minnesota State Census for Bancroft Township, Freeborn County taken on June 5th, 1905 it states that Hans has lived at his current residence for 49 years and six months. This date agrees almost to the day with the land records of when Hans bought his farm land. The deeds to Hans's farm show that he bought it from William Morin on November 7th, 1855. But in Ole K. Morreim's obituary it states that they arrived in 1856 and that they staked their claims in the fall of 1856. Hans's sister's Isabell Osmonson's obituary stated that he hauled the first load of merchandise into Albert Lea, Minnesota in 1855. The year in Isabell's obituary agrees with the land records for when Hans arrived, but it disagrees with Albert Lea historical records for when the first store open. According to Albert Lea historical records the first store didn't open until 1856. According to Ole Morreim's obituary they arrived in the Albert Lea area in 1856 which agrees with the open of the first store in Albert Lea. About the only scenario that I can think of where all this information aligns is that prior to November 7th Hans traveled from Goodhue County to the Albert Lea area looking for land to purchase. Then on the 7th he bought the land from William Morin for his farm. After purchasing his farm land he may have returned to Goodhue County till the spring of 1856. I feel that he may have returned to Goodhue County because there was a good chance that there wasn't anywhere to live on the property that he had bought, no wood cut for the winter or supplies to live on. With winter starting there wasn't any time to do any of these things till spring. William Morin was a major land speculator in the area and probably hadn't made any of these improvements to the property. When Julius Clark opened the first store in Albert Lea in 1856 he might have hired Hans to haul the merchandise for the store from Red Wing to Albert Lea. I've read that Julius Clark purchased his merchandise from the east and had it shipped to Minnesota. Where it was shipped to I'm not sure. Albert Lea was connected to the Mississippi River by several trails. The two main trails were from Red Wing, Minnesota and McGregor, Iowa. The merchandise may have come from Red Wing to Albert Lea as it's about forty miles closer than McGregor. If the merchandise did come to Red Wing it's possible that Hans and others, possibly the Morreim brothers help haul it to Albert Lea. As far as the date of 1856 for staking their claim it may have been that the Morreim brothers staked their claims at that time, but not Hans since he had already bought his land.

Note on the Morreim family. There was other information in Ole Morreim's obituary that got me to wondering about the relationship between the Kjonaas and Morreim families. This is what I found upon further research.

The Morreim family came from the Tinn district in Telemark, Norway. Tinn is the next district to the northwest of Bø. From the center of Bø to the center of Tinn is about thirty miles. Not knowing where the Morreim family lived in Tinn all I can say is that the families lived about thirty miles or so apart in Norway. The Morreim family left Telemark about two weeks before the Kjonaas family left. They may have traveled together from Norway to Le Havre, but I don't know this for sure. It appears that they met for the first time for sure in Le Havre, France. Both families traveled to the US onboard the ship Argo. On the Argo's manifest the name Kjonaas is misspelled and so is the name Morreim. The Morreim's name is misspelled as Marum and they are listed about three pages ahead of the Kjonaas family. The placement of the names on the ship's manifest makes me think that the Morreim family and the Kjonaas family didn't travel from Norway to Le Havre together. In Ole's obituary it states that his family arrived in Muskego in July of 1843, but this is a mistake. According to records the Argo arrived at the Port of New York on July 26th, 1843 and it wasn't possible to make it from New York City to Muskego before the end of the month of July. After arriving in New York it's possible that the families then traveled together all the way to Muskego, Wisconsin. According to Ole's obituary we know that the Morreim's traveled by way of the Erie Canal and the Great Lakes to Milwaukee, Wisconsin. From Milwaukee they traveled the twenty miles to Muskego. From Ole's obituary we know that the Morreim and Kjonaas families both attended the same church in Muskego. So it's probable that the Morreim and Kjonaas families stayed friend or at least acquaintances while in Muskego. It appears that the Morreim boys and Hans had a close enough relationship that they moved to Goodhue County, Minnesota and lived together for several years. In Ole Morreim's obituary it also states they staked their claim in 1856. I had information that the Morreim brothers settled in Manchester Township in Freeborn County. Using plat maps of Manchester Township I was able to locate the Morreim farms. Even after their move to Freeborn County the two families stayed close. In 1857 the rest of the Morreim family moved to Manchester. The Morreim family bought land starting on the west side of Hans's farm and going to the west and north for about another mile and a half.

Hans is the only child of Ole's that I have any physical description of and that came from his military records. He was 5' 6" in height. He had light complexion, brown hair and blue eyes.

Hans bought his 155 92/100 acre farm in Bancroft Township, Freeborn County, Minnesota on November 7th, 1861 from William Morin. According to the land records staff at the Freeborn County Courthouse William Morin was probably a land speculator and they said that they see his name come up a lot on property. From the records at the Freeborn County Courthouse William Morin came into possession of the property by the Bounty Land Act of March 3rd, 1855 in the name of Gwen Geramrack (this is as close as JoAnn and I can make the name out as), on November 5th, 1861 on Military Land Warrant No. 96339 at Winnebago City, Minnesota. Winnebago City is now Winnebago, Faribault County, Minnesota. On June 5th, 1866 he bought another twenty acres from Jacob and Mary Frost for $75. This land description was North Half of North East quarter of North West of Section 19. In layman's terms this would have been the north twenty acres of what would become the Osmonson Farm. The farm was located in the Southwest corner of Section 18 and the Northwest corner of section 19. The farm is located near the southwest corner of present day Bancroft Township Road 156 / 750th Ave. and County Highway 25 or about 6 miles north of downtown Albert Lea, Minnesota. The deed said that Han's bought the property for one dollar. When I asked at the Courthouse if that could be the accurate purchase price I was told that the actual amount was not required to be disclosed in those day and it was whatever they wanted to put the price at and it was usually one dollar. Manley Kjonaas though he had records that stated Hans paid a dollar and a half an acre.

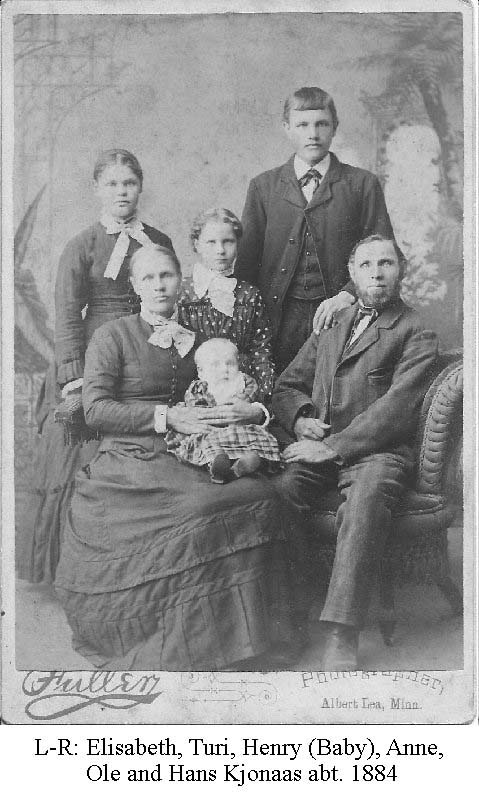

Hans married Turi Hefta on February 11th, 1863 at Manchester, Freeborn County, Minnesota. The marriage was performed by the Rev. Clausen and is recorded in the Record Book No. 1 at the First Lutheran Church in St. Ansgar, Iowa. Hans and Turi didn't attend this church. The Rev. Clausen was the Norwegian circuit preacher for the Albert Lea area and the First Lutheran Church in St. Ansgar was his home church, so all his records were kept there. Turi Hefta was born November 18th, 1842 in Sigdal, Buskerud, Norway. She immigrated with her family in 1851 and they lived at Jefferson Prairie, Wisconsin for a while. I've had problems finding information about her family during their immigration and their time in Wisconsin. In Norwegian tradition her name would have been Turi Helgesdatter. Her father's name in Norway was Helge Hefta. But it appears that after he arrived in the US that he used the surnames of Hefta, Hefta Nelson, and Nelson. By the time of his death he was going by Helge Hefta (as a middle name) Nelson. So with all these names it been hard to trace the family. From records that I've seen it looks like most of her life she considered Hefta as her surname. But when she applied for her Veterans Widow Pension on November 8th, 1909 she listed her maiden name as Nelson. I've seen her first name in records as Turi and Ture and other variations of these names. It appears that she couldn't write. On her Widow's Pension application she put her mark and it appears that someone wrote her name in. Our family has referred to her as Turi Hefta.

Hans's Military Service

On September 1st, 1864 Hans enrolled (enlisted) in the Union Army at Bancroft Township, Freeborn County, Minnesota. For enrolling it looks like he received a bounty of one hundred dollars. His military records only show that he was ever paid thirty three dollars and thirty three cents of this bounty. Then it looks like he was charged seventeen dollars and sixty seven cents for uniforms, a cartridge belt and cartridge box. He was mustered in on the same date at Rochester, Olmstead County, Minnesota. At Fort Snelling, Minnesota on September 12th he was assigned to the 4th Regiment Minnesota Infantry Volunteers. On September 19th he was assigned by Special Order Number 43 while at a depot somewhere. That is all the information that I have to go on about this depot. I've been unable to find out what Special Order Number 43 is also. He was assigned to Company F of the 4th Minnesota Infantry Regiment. Records make it look like he was assigned to Company F before he arrived, but the history of the 4th Minnesota Regiment talks about assigning new recruits to Companies after they arrive.

A breakdown of the chain of command for Hans's unit from the top down would have been the U. S. Army, Army of the Tennessee, 15th Corps, 3rd Division, 1st Brigade, 4th Minnesota Infantry Regiment, Company F. After March 31st, 1865 the 4th Minnesota was moved to the 2nd, Brigade. During the Carolina Campaign there were two wings of the Army of the Tennessee. Hans was in the right wing. These were the Commanding General in charge of the different units that commanded Hans. General William Sherman commanded the Army of the Tennessee. General Oliver Howard commanded the Right Wing of the Army of the Tennessee. General John Logan commanded the Fifteenth Army Corps. General John E. Smith commanded the Third Division. General William T. Clark commanded the First Brigade. Colonel Tourtellotte commanded the Fourth Minnesota Infantry Regiment.

Hans arrived at Allatoona, Georgia about October 1st, 1864. He was part of a group of eighty recruits that arrived that day to replace sick, wounded and veterans soldiers who's enlistment were up. On September 14th, 16th, and 18th the 4th Minnesota had previously received two hundred and seventy one new recruits. Because of so many replacements the 4th Minnesota was about fifty percent new recruits at the time of the battle. Many of the soldiers of the 4th Minnesota were green and had very little training prior to the battle. According to the history of 4th Minnesota some soldiers were being trained on how to load and fire their weapons the night prior to the battle. Hans had about a month of military time before he saw his first combat action. Most of which was spent in travel from Minnesota to Georgia. Having arrived at Allatoona only a few days prior to the battle Hans probably was one of these green troops getting this training the night before. A few days previous to the battle three NCO had placed markings on the ground from one hundred to five hundred yards distance from the fort in an effort to help these green soldiers to be more effective.

Today the Allatoona Battlefield borders the western shore of Lake Allatoona about 1.5 miles east of Emerson, Georgia along the Old Allatoona Rd. The battle fought there on October 5th, 1864 has a number of myths and legends. Most of these myths and legends come from disagreements in what was being signaled between General Sherman and General Course before, during and after the battle. The main disputed point is that General Course thought General Sherman was coming to his aid, but Sherman never signaled that. Sherman signaled that he would help Course. The battle was the inspiration for the hymn by Evangelist Peter Bliss, "Hold the Fort". The battle had one of the highest casualty percentage rates of the Civil War. There were battles where more were killed and battles that lasted longer, but for the number killed for the length of time of the engagement the casualty rate is only equaled by the battle at Gettysburg. By most account the number engage in the battle appeared to be 5,301 men (2,025 Union and 3,276 Confederate). Official Casualties rates were Union 35% and Confederate 27%. Casualties rate vary in many reports due to the different sources. I've seen Official Reported casualties of 1,063 to nearly 1,600. There are several reasons for such varying casualty rates. Many of the casualty reports were filed

within several days of the battle yet; there are reports of bodies being found and buried up to October 22nd, over two weeks after the battle. Also some that were listed as wounded died several days later from their wounds. Another complication was the two sides didn't use the same methods for daily accounting for their personnel. The Confederate casualty rates are very hard to determine. Several senior Confederate officers placed their losses between 1,500 and 2,000. Yet the official estimates of Confederate losses range from 799 to 897. This wide variance in numbers could be due to the fact that the wagons that the Confederates had planned to use in removing the supplies from Allatoona warehouses instead carried many of their wounded and killed from the battlefield. There were so many confederate wounded left on the battlefield that General French left some of his medical staff on the battlefield to care for the wounded that he couldn't take with him.

Here is some background of what happened before the battle of Allatoona Pass. Union General Sherman took Atlanta on Sept. 2nd, 1864 after defeating Confederate General Hood in a series of battles in and around Atlanta. With Sherman firmly in possession of Atlanta, Hood decided to move his troops to the north towards Chattanooga, with these goals in mind: Disrupt Sherman's supply and communication line on the Western and Atlantic Railroad (W&A RR) connecting Atlanta to Chattanooga, Force Sherman to backtrack on his North Georgia gains and to invade Tennessee. The battle of Allatoona Pass is considered by most to be the first battle in Hood's Nashville Campaign. This campaign was the last major Confederate Offense of the Civil War.

The strategic importance of the battle was the Union's defense of the W&A RR through a cut in the Allatoona Mountains range known as the Allatoona Pass. It was approximately 360 feet long, 175 feet deep and 60 feet wide. About 90 feet from the top on each side is a flat "berm" to catch falling rocks and such. The Pass was the deepest rail cut along the W&A between Atlanta and Chattanooga. Allatoona was also the intersection of the Tennessee Road and the old Alabama Road. The Alabama road is also called the Carterville Road on some maps. During his advance on Atlanta in June of 1864 General Sherman avoided the Allatoona Pass due to its defensive capabilities. After the Confederates had vacated the Pass, Sherman had his Engineers design a system of forts and trenches that would take full advantage of the Pass's natural strengths. The fortifications would not only protect the railroad, but also the supply depot at Allatoona. The supply depot at Allatoona was the Union's main supply depot south of Chattanooga. By the fall of 1864 the Warehouses at Allatoona contained at least one million rations of hardtack.

The fortifications at the pass had been designed to protect about 800 men. General French described the forts as having walls twelve foot thick, six foot high with a six foot ditches in front of them. The Star and Eastern Forts were about 75 ft. in diameter. Prior to the battle the pass was garrisoned by 966 men. The Garrison was manned by 280 men of the 93rd Illinois, 150 men of the 18th Wisconsin, 450 men of the 4th Minnesota, 15 men (a Detachment) of the 5th Ohio Cavalry and 71 men of the 12th Wisconsin Battery. The Garrison Commander was Lt. Col. John E. Tourtellotte. Tourtellotte was normally the commander of the 4th Minnesota, but as senior officer he was Garrison Commander prior to the battle and Major James C. Edson was the commander of the 4th Minnesota at the time of the battle.

Between October 3rd and 4th, Hoods forces tore up fifteen miles of track near Acworth/Big Shanty on the A&W RR south of Allatoona. This action served as the preliminary for the battle at Allatoona Pass that was to come. In response to Hood's movements, Sherman had sent General Corse and his division to defend Rome, GA and marched half of his army towards Marietta. By October 4th, Sherman had learned that 3,276 troops under Confederate General French were headed towards Allatoona Pass. There are different reports that state that Sherman couldn't have made it to Allatoona Pass in time to stop the Confederate attack due to the distance, but it's known that Sherman did know most of Hood's plans because they had been printed in southern Newspapers after President Davis made a speech to the Confederate troops that detailed the plans of the Campaign. It's never really been answered why Sherman wasn't in a position to stop Hood from attacking his supply line at Allatoona. What is known is that Sherman sent General Corse a message to move his Division from Rome to Allatoona Pass on October 4th, about a thirty mile trip by train. General Corse managed to ship 1,054 of his men from Rome to Allatoona Pass in time for the battle. However, the railroad transit had many difficulties:

"The train, in moving down to Rome, threw some fourteen or fifteen cars off the track, and threaten to delay us till the morning of the fifth, but the activity of the officers and railroad employees enabled me to secure a train of twenty cars about 7 p.m. of the 4th. Onto them I loaded three regiments of Colonel Rowett's brigade and a portion of the Twelfth Illinois Infantry, with about 165,000 rounds of ammunition, and started for Allatoona at 8:30 p.m., where we arrived at 1 a.m. on the morning of the 5th instant, immediately disembarked, and started the train back, with injunctions to get the balance of the brigade and as many of the next brigade as they could carry and return by day-light. They unfortunately met with an accident that delayed them so as to deprive me of any re-enforcements until about 9 p.m. on the 5th" (Official Report)

General French was ordered on October 4th to march on Allatoona Pass and fill the railroad cut, move on to the Etowah River and destroy the bridge there and then meet Hood at New Hope, GA. This would have been a difficult task for General French to have accomplished in the time allowed by Hood. To further complicate the mission the cut was heavily fortified on both sides, a fact that General French later pointed out was possibly unknown to his superiors and the task was almost impossible to accomplish. It also appears that General French was un-aware that that Allatoona Pass had been re-enforced with more troops. His local guide informed him that it was protected by three and a half regiments of infantry and four pieces of artillery. According to the memoirs of a soldier from the 93rd Illinois the troops at Allatoona Pass could hear the fighting going on to the south of them during the day of October 4th and they slept in the trenches and fortification with their weapon at ready the night of October 4th.

Lt. Colonel Tourtellotte wrote:

"My first unpleasant apprehensions were that the rebels would make a night attack, and taking advantage of the darkness depriving me of the advantage of position, the fortifications of this place all being on the high ridge while the stores are collected on the flat land at the hill's base and on the south side, from which direction the rebels were approaching. To prevent such approach I strengthened the grand guard, barricaded the roads to the south and made preparations to fire a building which should so illuminate the site of the village and stores that my men could see, even in the night, to a considerable extent any approach of the enemy. In this way I hoped to hold the rebels till daylight, when we should have the full advantage of our superior position.

About 12 midnight I was not a little relieved by the arrival of General Corse with one brigade, Fourth Division, Fifteenth Army Corps. About 2 a. m. of October 5th the rebels charged upon my picket-lines and drove the outposts back upon the reserves."

Note: Many stories of the battle give different times for events that happened. There are a number of reasons for this. During the battle you didn't have anyone recording the exact times that something happened, so times were recorded from memories and what the recorder of the event thought the time was. Very few of the higher ranking officers owned a watch much less junior officer or the enlisted. Then you also have the problem of different watches being set to different time. You didn't have a Radio, TV or Cell Phone to set your watch to. So if you had a watch it may have been set to some clock in a town that you passed thought or the guy next to you.

Starting around 7:00 a. m. the Confederates opened an 11 cannon artillery barrage on the fortified Union positions. According to the memoirs of the soldier from the 93rd Illinois this artillery barrage did very little damage and several of the Confederate guns were put out of commission by the Union guns and the Confederate guns were forced to withdraw out of range of the Union guns. According to the history of the 4th Minnesota there wasn't anyone injured or killed from this barrage, but it did kill all 27 horses of the 12th Wisconsin Battery. During this bombardment French continued to move his forces into position for attack, with General Young and General Cockrell to the west and General Sears to the northwest and north of the forts. No attacks came from the east due to the Allatoona River that was there and is now under Lake Allatoona. Sometime about 9:00 a.m. General French, thinking that he had the forts surrounded and significantly outnumbered sent an ultimatum to General Corse to surrender:

"SIR: I have placed the forces under my command in such position that you are surrounded and to avoid a needless effusion of blood, I call on you to surrender your forces at once and unconditionally. Five minutes will be allowed you to decide. Should you accede to this you will be treated in the most honorable manner as prisoners of war."

It is agreed upon by both side that French's message of surrender was received by General Corse. But from that point on it's another part of the legend and myths of the battle. General French said that he never got Corse's reply. It's not know if Major Sanders, who waited seventeen minutes for the message never received it, never gave it to French, left before the message was sent or if French's troops jumped the gun and started firing as soon as the Major returned to the Confederate lines and Major Sanders didn't feel the need to deliver the message to General French. Another thing that may have complicated things is that during this time under the white flag of truce that the confederates continued to advance and improve their positions prior to the battle in violation of the code of the truce. General Corse replied with the following answer:

"We are prepared for the ‘needless effusion of blood' whenever it is agreeable to you."

It isn't my intent in this story to tell all about the battle. While it's very interesting it's too long for this narrative.

This is a summation of the battle. Starting about 3:00 a.m. there were skirmishes between the two forces as the outer pickets met. The Union Troop fell back to their rifle pits and forts and the Confederate Troops advanced around Allatoona Pass taking positions on the south, west and the north sides of the pass. Depending on the report about 9:00 a.m. the fighting started after the Union was asked to surrender. By 11:00 the Union Troops in Rowett's redoubt to the west of the Star Fort and the outer trenches and rifle pits had been overtaken by Confederate forces. The Union forces still held both Forts and the trenches protecting both forts. Between 11:00 a.m. and some reports say 12:00 and others say 1:00 p.m. at least four assaults on the forts were made by the Confederates. At times the fighting in the trenches was hand to hand, but all the assaults were repulsed. Some reports state that the Union Troops were outnumbered four to one in some of these assaults.

About 11:00 a.m. General Course ordered the 12th and the 50th Illinois Regiments to the west side. But in the confusion the 57th Illinois Regiment also moved to the west side leaving the 4th Minnesota Regiment along with four companies of the 18th Wisconsin Regiment to man the east side of the pass.

There are stories of soldiers that had been wounded a number of times that kept fighting. Nearly every Field Grade (Major and above) Union Officer on the west side was wounded or killed during the battle rallying the troops. There was an account of a soldier on the east side with the 4th Minnesota that had an arm amputated and went back to the line to drag hundred pound boxes of ammunition to the troops still fighting. This man died a couple of days later due to blood poisoning.

The 7th Illinois Infantry had Henry repeating rifles, with a 16 shot magazine and they are one of the reason that the Union forces were able to withstand these Confederate assaults. These weapons had been purchased and shipped at the expense of Captain John Smith of the 7th Illinois Infantry. Another report stated that the men bought the Henry Rifles for themselves for $52 a person. These rifles had arrived just days before the battle. The Henry was a predecessor to the Winchester Rife and looked similar. This was the first time that many of the Confederate Troop had ever run into these weapons.

To increase the rate of fire in the Star Fort they had groups of three men working together. Two would load weapons and the third would fire. About 12:00 according to a soldier memoir from the 93rd Illinois and 2:30 according to General Course's report the Star Fort lost one of their Rodman artillery guns when a shell jammed in the barrel. Another artillery piece in the Star Fort had to be moved across the fort and into position to replace the disabled gun. There were so many wounded and dead within the fort that it took almost an hour to move and have the replacement gun ready to fire on the Confederate forces. During this time Confederate sharpshooters and troops were continually firing on the Star Fort from a nearby house and barn and from behind stumps making it nearly impossible for the men inside the Star Fort to return fire. The Star Fort did have a design flaw. The Union Troops had to expose themselves to fire over the top to return the Confederate fire. After the artillery piece was in place it was able to destroy the buildings and cover that the Confederates were using to fire on the Star Fort.

One story stated that the Confederate fire was so heavy that the artillery pieces had to be load by soldiers laying on the ground so as not to be shot during the loading and firing process. The Union artillery pieces were firing so fast and often that they began to overheat and they had to have time to cool off. The artillery pieces were firing loads of double grape or canisters of shot most of the time. Loading them this way made them the same as a very large shotgun. The artillery on the west side was going through so much ammunition that Edwin R. Fullington, a private of the Twelfth Wisconsin battery, crossed and re-crossed the narrow and rickety footbridge over the railroad cut three times, under direct fire from the enemy, and carried grape and canister ammunition from the Eastern Fort to the Western Fort. Many of the men of the Twelfth Wisconsin battery were killed trying to man and fire their pieces. One of the men manning the artillery in the Star Fort later received the Congressional Metal of Honor for his bravery during the battle. Prior to the battle the Twelfth Wisconsin Battery had received a new flag. This flag was located in the Western Fort during the battle. After the battle ended, there were one hundred and ninety-two bullet holes in that flag. It told the story of a terrible battle.

About 2:00 AM the fighting slowed. The Union Troops in the Star Fort were low on ammunition and the Confederate Troops weren't assaulting the Forts, but firing on them from cover. While most of the fighting was in the north-west, western and south-west sides of the pass the eastern side where Hans and the 4th Minnesota fought saw its share of battle also.

Here is an excerpt from the memoir of the same 93rd Illinois soldier.

"The fighting east of the railroad cut was the counterpart of that on the west side, except that it was less severe. On that side, also, two or three charges were attempted by the enemy, and repulsed; but the numbers of the assaulting forces there were much less than of those on the west side, the ascent to the fort and entrenchments was steeper, and the starting point was farther away. The Federal force there was only about one-half as great as that on the west side, but they were better distributed, and the fortifications were better and better located. Hence, the main attack and most of the vigorous fighting of the enemy was on the west side of the railroad cut. Nevertheless, that on the east side was quite severe, and was maintained with great persistency to the end. A part of the troops on the east side were so located that they could, and at times did, render valuable assistance to those on the west side. But the greater part of the time they had all they could reasonably be expected to attend to on their own side of the railroad. As a matter of fact, however, they attended to what they had to do there, and did it remarkably well, and still had a few spare moments in which they sent many whistling messengers to the enemy across the railroad. The last charge of the enemy on the east side of the railroad cut was made, a little before noon, by the Thirty-fifth and Thirty-ninth Mississippi regiments. They suffered heavy losses, and the large part of both regiments retired from the onset."

Some reports felt that the Confederates fought on after the last assault was defeated about noon in the hope they might capture the rations stored in the warehouses at Allatoona. French's men had brought two hundred wagons with them for this purpose. There are stories that General French had told his men that they would be eating the Unions Armies food by 10:00. After the battle it was found that many of the dead Confederate soldier knapsacks didn't have any provisions in them or they only contained ears of field corn with a pan with holes punched in them to grind the corn into corn meal. In retrospect one of the great failures of the Confederate attack was leaving the Federal supplies intact.

I have read several reasons why this happened. The following are the most common.

General French later gave this explanation as to his failure to destroy the Union supplies at Allatoona: "Before withdrawing ordered the stores be burned at the depot. Parties were sent, but all efforts they could make failed to procure fire. The matches furnished would not ignite, and no fire could be procured. The enemy's fire concentrated too protect their stores was heavy and incessant all the time." (Official Report)

Another version of what happened from the memoir of the same 93rd Illinois soldier: "About 2 o'clock in the afternoon, after the Confederates had concluded that they could not take Allatoona, they made an effort to burn the rations. A Lieutenant Colonel of a Texas regiment, at the head of more than a hundred picked men, with many burning fagots in their hands, made a rush from behind the ridge, into the road near the foot of the hill west of the south end of the railroad cut, and attempted to reach and fire the warehouses. A well-directed volley of musketry, laid nearly forty of them dead in their tracks in the road, and many more were wounded. The force was shattered. Only a few of them reached the nearest warehouse. It was said, that one of them burst the door and entered, and was immediately cut down, with an ax, by Lieutenant Colonel Tourtellotte's (SIC) negro servant. One or two others were killed in the building, and several near it.

Another story states, "A Confederate Lieutenant, maddened by their frequent repulses, seized a firebrand and made a rapid run, from a house near the railroad depot, toward the nearest warehouse, for the purpose of applying the torch. He fell dead before reaching the warehouse. A good marksman sent a bullet that pierced the center of his forehead."

About 3:00 p.m. General French started withdrawing his forces, by 4:00 p.m. the battle was over.

Why did the battle end? Again there are a number of different stories of what happened.

Supposedly there was a Confederate Calvary report that Union re-enforcements were on the way.

There is another report that they thought that the en-coded signal flag messages were signaling that General Sherman was on the way.

General French stated that his men were exhausted after three days of fighting, couldn't hold the pass because Union re-enforcements were on the way, they were low on ammunition and they would have to wait two hours to be re-supplied. He also didn't want to be cut off from the rest of General Hood's Army during his retreat by the advancing Union Army that he thought was coming.

The Union forces also were low on ammunition and had suffered great losses.

General Course felt that he had beaten the Confederates and driven them away in disarray.

General French wasn't driven away in disarray either. He had the time to capture a block house and burn two bridges as he withdrew. Both sides agreed that another assault on the Forts would have probably been successful.

Some official records appear to be exaggeration or written to cover or justify mistakes that might have been made by a commander. One exaggeration by General Course was about the wound he received during the battle. On the 6th General Course signaled to Sherman, "I am short a cheek bone and one ear, but am able to whip all hell yet. My losses are very heavy." When Sherman saw General Course several days later, he commented, "Corse, they came damned near missing you, didn't they?"

The sad epitaph to the story of the Battle of Allatoona Pass is that after all the lives that were lost and all the injuries cause by the battle on November 9th, 1864 as Sherman prepared to commence his March to the Sea, he issued orders to destroy the very railroad that he had fought so fiercely to protect the month before.

Hans was severely wounded in the left thigh by a bullet in the Battle of Allatoona. Hans stated in his veteran's pension application that he was treated on the battlefield by a surgeon that he didn't know who he was, since he had been with the unit for only three days. His pension records state he was sent to an Army Hospital at Rome, Georgia where he received further treatment from October 10th to November 5th, 1864. But his service records state he was absent since October 8th in Hospital. From Rome he was transferred to a Hospital at Chattanooga, Tennessee from November 6th or 7th to December 1st, 1864. From there he was sent to Nashville, Tennessee for further care until about December 20th, 1864. He was then transferred to one of the two Military Hospitals in St. Louis, Missouri until December 30th, 1864. While in these hospitals he contracted something that caused him chronic diarrhea and joint pain the rest of his life. His doctors thought he had Rheumatoid Arthritis. He may have also contracted dysentery which was a common problem during the civil war.

While Hans was in the various hospitals General Sherman completed his "March to the Sea" and captured Savanna, Georgia. After capturing Savanna Sherman turned his army and started it marching up the east coast on his Carolinas Campaign. On the march up the eastern coast, Han's Regiment mainly did patrols and rear guard action. While performing these actions they were involved in many skirmishes and were on the edge of a number of battles, but they were never involved in a pitch battle as in Allatoona again during the war. Sherman's Carolinas Campaign continued the practice of living off the land that he had used on his "March to the Sea. The march up the east coast started on January 5th, 1865. During this campaign the weather was terrible. Many of the roads were impassable due to rain, mud and flooding. The retreating Confederate Army was also destroying as much of the food sources as they could in their retreat. In the history book of the 4th Minnesota it's stated that they lost more men killed while scavenging for food then they did to military action. We call it living off the land now, they called it scavenging or bumming. By the time the unit got to North Carolina many of the men and officers were shoeless and their uniforms were in tatters. Most didn't have coats or blankets. If your blanket was wet in the morning when you had to leave you had to discard it, because you weren't given the time to dry it out before you would be forced to march on. So, most of the men hadn't had a blanket since the beginning of the campaign. For most of the campaign they were without many supplies such as coffee, sugar, bandages or medicines. According to the Regimental History Book the conditions were freezing rain, cold, wet and muddy most of the time. Men were used as mules and horses at times to pull wagons through the mud and bad roads when horse and mules couldn't.

It appears that Hans was released from the hospital about December 31st, 1864, but he isn't on the Regimental Roll as present until March. The Roll only list the whole month. When he was wounded it stated on the Roll the date he left for the hospital, but when he came back it's just listed as March and that he was present. Where he was for January and February I don't know. How he got back to the Regiment I don't know and it's not in any of his records. If he rejoined the Regiment on March 1st they would have been at Chesterfield, South Carolina. Hans's Brigade was at the Battle of Bentonville, North Carolina on March 19th - 21st, but didn't participate in the battle. They were held in reserve and preformed rearguard duty. They were still close enough to the action that several in the 4th Minnesota were wounded from shells and bullets. They occupied Goldsboro, North Carolina on March 24th and advanced on Raleigh, North Carolina on April 10th - 14th which they occupied on the 14th. General Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia on April 9th, 1865 and General Johnston surrendered his Army of the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida to General Sherman on April 26th. The war in the east had ended.

Things didn't get any better for the men after the Confederate surrendered. They still didn't have any supplies and now they couldn't live by scavenging anymore, because the areas they were traveling through were now part of the U.S. again after the surrenders of the Eastern Confederate Armies. Before he left for Washington DC General Sherman gave his Corps Commanders orders to march to Washington, DC for the Grand Review. They were to march ten miles a day and not on Sunday. But these Corps Commanders got into a race with each other to see who would be the first to reach Washington for the Grand Review. From April 29th to May 20th they marched as rapidly as possible (18 to 25 miles a day) to Washington, DC. On most days reveille was around 3:00 a.m. On the way to Washington, DC they passed through Petersbough, Richmond, Fredericksburg, Dunfries, Mt. Vernon and Alexandria. On May 24th, 1865 the 4th Minnesota marched at the head of Sherman's Army of 65,000 through the streets of Washington, DC during the Grand Review. The review of Sherman's Army took six and a half hours. On May 31st they boarded a Baltimore and Ohio Railroad train near Washington D.C. They traveled via Harpers Ferry, West Virginia; Cumberland, West Virginia, to Grafton West Virginia where they arrived on June 1st. From Grafton they traveled on the Parkersburg Railroad to Parkersburg West Virginia on the Ohio River arriving there on June 2nd. The same day they embarked on the steamboat Champion to Louisville, Kentucky where they arrived on June 4th. At Louisville they camped about three miles west of the city near the Ohio River.

According to Hans's military records he was Mustered Out on June 12th, 1865 with two hundred other. That two hundred men were mustered out on the 12th is confirmed by the 4th Minnesota history. According to the 4th Minnesota history he wasn't mustered out until August 12th. I think this is a misprint in the book, because the 4th Minnesota was paid and disbanded by August 7th, 1865. What Hans had to do between June 12th and July 19th I don't know and it's not in any records that I can find.

"July 19th – Wednesday – We were mustered for discharge out of the United States service at five o'clock to-day, by Capt. W. S. Alexander of the Thirtieth Iowa Infantry, assistant commissary of muster First Division, Fifteenth Army Corps.

Headquarters Army of the Tennessee

Louisville, KY., July 19, 1865

Special Orders, No. 103:

Fourth Regiment Minnesota veteran Volunteer Infantry, having been mustered out of service in accordance with General Orders, No. 26 (current series), from these headquarters, the quartermaster's department will furnish transportation from Louisville, Ky., to Fort Snelling, Minn., for 43 officers and men and seven private horses belonging to the officers of the command.

By command of Maj. Gen John A. Logan."

On July 20th at 1:00 p.m. they crossed the Ohio River to Jeffersonville, Indiana where they boarded a train. They arrived at Chicago at 6:00 a.m. on July 22nd after traveling through Indianapolis and Kokomo, Indiana. They had breakfast at the Soldiers' Rest in Chicago, Illinois and then re-board the train and arrived in Milwaukee, Wisconsin at 3:00 p.m. At Milwaukee they went to the fair and had supper with the Eighteenth Wisconsin Regiment whom they had served with. They departed Milwaukee by train at 6:00 p.m. on the 22nd. On July 23rd at 10:30 they arrived in La Crosse, Wisconsin where they boarded the steamboat Northern Bell. Part of the regiment was on the boat and some of it was on a barge. They departed La Crosse at 2:00 p.m. and arrived at St. Paul, Minnesota on July 24th at 6:00 p.m. After they disembarked they marched to the capital and had supper. After supper they returned to the boat for their possessions and they were given permission to go home, but they had to report back on August 5th. They then were addressed by the Governor and Mayor. After lots of cheering, rain and mud the men dispersed.

When the soldiers of the 4th Minnesota returned to St. Paul on August 5th they still had to wait until August 7th to sign the pay rolls and received their final discharge when they were let go as free citizens once again. This was the first time that Hans's had been paid in almost a year.

After his return from the war Hans returned to the farm in Bancroft Township. After all the activity of his earlier life, his life after his return from the Civil War appeared to be that of a quiet family man and farmer. I haven't found where he belonged to any groups, held any kind of public office, was recognized for any special achievements or attended any of the 4th Minnesota Infantry Reunions. It appears that the 4th Minnesota historian didn't even have an idea where he lived. After his return the farm continued to develop and it turned into a successful operation where he raised his family. Hans never fully recovered from his medical problems from the war. His health problems were severe enough that he was event-ually totally disabled.

Hans was granted a Veterans Pension in 1888 due to his military disabilities. Hans lived on the farm until his death on October 15th, 1909. Hans was buried at Graceland Cemetery, Albert Lea, Minnesota, Section 4 (Original), Lot 41.

Hans has been a hard member of the family to track for the early part of his life. From the families arrival in the US in 1843 to 1855 Hans location wasn't know for sure for a long time. Hans is not listed in the 1850 census as living with his father. It's possible that he was living in the Rochester, Racine County, Wisconsin area at the time of the 1850 Census. I've found a Hans Oleson who was listed as a laborer and attending school. This Hans Oleson was living with the Areatus Bailey family in the 1850 Federal Census for Rochester, Racine County, Wisconsin. The age and everything is right for our Hans and Rochester is only eight miles from the Evenson homestead. But I don't have any way to confirm it's him and Oleson is such a common name. In the summer of 2013 Linda Evenson, the librarian for the Freeborn Historical Society found an obituary for Ole K. Morreim that helped confirm Hans's residence for some of the missing years. According to Ole Morreim's obituary on Page 5 of the Albert Lea newspaper The Evening Tribune dated November 4th, 1915 Hans came to Minnesota with Ole and his brother Thosten in 1854. In Ole's obituary it states, "In 1854 Ole, together with his brother Thosten and Mr. Hans Olsen Kjonaas, left for Minnesota, traveling by ox team, they arrived in Goodhue Co. that fall, stayed there only a year and a half when they moved to Freeborn Co. where in the fall of 1856 they filed on claims which they have kept every since". There is a conflict with these dates and other information sources. In the 1905 Minnesota State Census for Bancroft Township, Freeborn County taken on June 5th, 1905 it states that Hans has lived at his current residence for 49 years and six months. This date agrees almost to the day with the land records of when Hans bought his farm land. The deeds to Hans's farm show that he bought it from William Morin on November 7th, 1855. But in Ole K. Morreim's obituary it states that they arrived in 1856 and that they staked their claims in the fall of 1856. Hans's sister's Isabell Osmonson's obituary stated that he hauled the first load of merchandise into Albert Lea, Minnesota in 1855. The year in Isabell's obituary agrees with the land records for when Hans arrived, but it disagrees with Albert Lea historical records for when the first store open. According to Albert Lea historical records the first store didn't open until 1856. According to Ole Morreim's obituary they arrived in the Albert Lea area in 1856 which agrees with the open of the first store in Albert Lea. About the only scenario that I can think of where all this information aligns is that prior to November 7th Hans traveled from Goodhue County to the Albert Lea area looking for land to purchase. Then on the 7th he bought the land from William Morin for his farm. After purchasing his farm land he may have returned to Goodhue County till the spring of 1856. I feel that he may have returned to Goodhue County because there was a good chance that there wasn't anywhere to live on the property that he had bought, no wood cut for the winter or supplies to live on. With winter starting there wasn't any time to do any of these things till spring. William Morin was a major land speculator in the area and probably hadn't made any of these improvements to the property. When Julius Clark opened the first store in Albert Lea in 1856 he might have hired Hans to haul the merchandise for the store from Red Wing to Albert Lea. I've read that Julius Clark purchased his merchandise from the east and had it shipped to Minnesota. Where it was shipped to I'm not sure. Albert Lea was connected to the Mississippi River by several trails. The two main trails were from Red Wing, Minnesota and McGregor, Iowa. The merchandise may have come from Red Wing to Albert Lea as it's about forty miles closer than McGregor. If the merchandise did come to Red Wing it's possible that Hans and others, possibly the Morreim brothers help haul it to Albert Lea. As far as the date of 1856 for staking their claim it may have been that the Morreim brothers staked their claims at that time, but not Hans since he had already bought his land.

Note on the Morreim family. There was other information in Ole Morreim's obituary that got me to wondering about the relationship between the Kjonaas and Morreim families. This is what I found upon further research.

The Morreim family came from the Tinn district in Telemark, Norway. Tinn is the next district to the northwest of Bø. From the center of Bø to the center of Tinn is about thirty miles. Not knowing where the Morreim family lived in Tinn all I can say is that the families lived about thirty miles or so apart in Norway. The Morreim family left Telemark about two weeks before the Kjonaas family left. They may have traveled together from Norway to Le Havre, but I don't know this for sure. It appears that they met for the first time for sure in Le Havre, France. Both families traveled to the US onboard the ship Argo. On the Argo's manifest the name Kjonaas is misspelled and so is the name Morreim. The Morreim's name is misspelled as Marum and they are listed about three pages ahead of the Kjonaas family. The placement of the names on the ship's manifest makes me think that the Morreim family and the Kjonaas family didn't travel from Norway to Le Havre together. In Ole's obituary it states that his family arrived in Muskego in July of 1843, but this is a mistake. According to records the Argo arrived at the Port of New York on July 26th, 1843 and it wasn't possible to make it from New York City to Muskego before the end of the month of July. After arriving in New York it's possible that the families then traveled together all the way to Muskego, Wisconsin. According to Ole's obituary we know that the Morreim's traveled by way of the Erie Canal and the Great Lakes to Milwaukee, Wisconsin. From Milwaukee they traveled the twenty miles to Muskego. From Ole's obituary we know that the Morreim and Kjonaas families both attended the same church in Muskego. So it's probable that the Morreim and Kjonaas families stayed friend or at least acquaintances while in Muskego. It appears that the Morreim boys and Hans had a close enough relationship that they moved to Goodhue County, Minnesota and lived together for several years. In Ole Morreim's obituary it also states they staked their claim in 1856. I had information that the Morreim brothers settled in Manchester Township in Freeborn County. Using plat maps of Manchester Township I was able to locate the Morreim farms. Even after their move to Freeborn County the two families stayed close. In 1857 the rest of the Morreim family moved to Manchester. The Morreim family bought land starting on the west side of Hans's farm and going to the west and north for about another mile and a half.

Hans is the only child of Ole's that I have any physical description of and that came from his military records. He was 5' 6" in height. He had light complexion, brown hair and blue eyes.

Hans bought his 155 92/100 acre farm in Bancroft Township, Freeborn County, Minnesota on November 7th, 1861 from William Morin. According to the land records staff at the Freeborn County Courthouse William Morin was probably a land speculator and they said that they see his name come up a lot on property. From the records at the Freeborn County Courthouse William Morin came into possession of the property by the Bounty Land Act of March 3rd, 1855 in the name of Gwen Geramrack (this is as close as JoAnn and I can make the name out as), on November 5th, 1861 on Military Land Warrant No. 96339 at Winnebago City, Minnesota. Winnebago City is now Winnebago, Faribault County, Minnesota. On June 5th, 1866 he bought another twenty acres from Jacob and Mary Frost for $75. This land description was North Half of North East quarter of North West of Section 19. In layman's terms this would have been the north twenty acres of what would become the Osmonson Farm. The farm was located in the Southwest corner of Section 18 and the Northwest corner of section 19. The farm is located near the southwest corner of present day Bancroft Township Road 156 / 750th Ave. and County Highway 25 or about 6 miles north of downtown Albert Lea, Minnesota. The deed said that Han's bought the property for one dollar. When I asked at the Courthouse if that could be the accurate purchase price I was told that the actual amount was not required to be disclosed in those day and it was whatever they wanted to put the price at and it was usually one dollar. Manley Kjonaas though he had records that stated Hans paid a dollar and a half an acre.

Hans married Turi Hefta on February 11th, 1863 at Manchester, Freeborn County, Minnesota. The marriage was performed by the Rev. Clausen and is recorded in the Record Book No. 1 at the First Lutheran Church in St. Ansgar, Iowa. Hans and Turi didn't attend this church. The Rev. Clausen was the Norwegian circuit preacher for the Albert Lea area and the First Lutheran Church in St. Ansgar was his home church, so all his records were kept there. Turi Hefta was born November 18th, 1842 in Sigdal, Buskerud, Norway. She immigrated with her family in 1851 and they lived at Jefferson Prairie, Wisconsin for a while. I've had problems finding information about her family during their immigration and their time in Wisconsin. In Norwegian tradition her name would have been Turi Helgesdatter. Her father's name in Norway was Helge Hefta. But it appears that after he arrived in the US that he used the surnames of Hefta, Hefta Nelson, and Nelson. By the time of his death he was going by Helge Hefta (as a middle name) Nelson. So with all these names it been hard to trace the family. From records that I've seen it looks like most of her life she considered Hefta as her surname. But when she applied for her Veterans Widow Pension on November 8th, 1909 she listed her maiden name as Nelson. I've seen her first name in records as Turi and Ture and other variations of these names. It appears that she couldn't write. On her Widow's Pension application she put her mark and it appears that someone wrote her name in. Our family has referred to her as Turi Hefta.

Hans's Military Service

On September 1st, 1864 Hans enrolled (enlisted) in the Union Army at Bancroft Township, Freeborn County, Minnesota. For enrolling it looks like he received a bounty of one hundred dollars. His military records only show that he was ever paid thirty three dollars and thirty three cents of this bounty. Then it looks like he was charged seventeen dollars and sixty seven cents for uniforms, a cartridge belt and cartridge box. He was mustered in on the same date at Rochester, Olmstead County, Minnesota. At Fort Snelling, Minnesota on September 12th he was assigned to the 4th Regiment Minnesota Infantry Volunteers. On September 19th he was assigned by Special Order Number 43 while at a depot somewhere. That is all the information that I have to go on about this depot. I've been unable to find out what Special Order Number 43 is also. He was assigned to Company F of the 4th Minnesota Infantry Regiment. Records make it look like he was assigned to Company F before he arrived, but the history of the 4th Minnesota Regiment talks about assigning new recruits to Companies after they arrive.

A breakdown of the chain of command for Hans's unit from the top down would have been the U. S. Army, Army of the Tennessee, 15th Corps, 3rd Division, 1st Brigade, 4th Minnesota Infantry Regiment, Company F. After March 31st, 1865 the 4th Minnesota was moved to the 2nd, Brigade. During the Carolina Campaign there were two wings of the Army of the Tennessee. Hans was in the right wing. These were the Commanding General in charge of the different units that commanded Hans. General William Sherman commanded the Army of the Tennessee. General Oliver Howard commanded the Right Wing of the Army of the Tennessee. General John Logan commanded the Fifteenth Army Corps. General John E. Smith commanded the Third Division. General William T. Clark commanded the First Brigade. Colonel Tourtellotte commanded the Fourth Minnesota Infantry Regiment.

Hans arrived at Allatoona, Georgia about October 1st, 1864. He was part of a group of eighty recruits that arrived that day to replace sick, wounded and veterans soldiers who's enlistment were up. On September 14th, 16th, and 18th the 4th Minnesota had previously received two hundred and seventy one new recruits. Because of so many replacements the 4th Minnesota was about fifty percent new recruits at the time of the battle. Many of the soldiers of the 4th Minnesota were green and had very little training prior to the battle. According to the history of 4th Minnesota some soldiers were being trained on how to load and fire their weapons the night prior to the battle. Hans had about a month of military time before he saw his first combat action. Most of which was spent in travel from Minnesota to Georgia. Having arrived at Allatoona only a few days prior to the battle Hans probably was one of these green troops getting this training the night before. A few days previous to the battle three NCO had placed markings on the ground from one hundred to five hundred yards distance from the fort in an effort to help these green soldiers to be more effective.

Today the Allatoona Battlefield borders the western shore of Lake Allatoona about 1.5 miles east of Emerson, Georgia along the Old Allatoona Rd. The battle fought there on October 5th, 1864 has a number of myths and legends. Most of these myths and legends come from disagreements in what was being signaled between General Sherman and General Course before, during and after the battle. The main disputed point is that General Course thought General Sherman was coming to his aid, but Sherman never signaled that. Sherman signaled that he would help Course. The battle was the inspiration for the hymn by Evangelist Peter Bliss, "Hold the Fort". The battle had one of the highest casualty percentage rates of the Civil War. There were battles where more were killed and battles that lasted longer, but for the number killed for the length of time of the engagement the casualty rate is only equaled by the battle at Gettysburg. By most account the number engage in the battle appeared to be 5,301 men (2,025 Union and 3,276 Confederate). Official Casualties rates were Union 35% and Confederate 27%. Casualties rate vary in many reports due to the different sources. I've seen Official Reported casualties of 1,063 to nearly 1,600. There are several reasons for such varying casualty rates. Many of the casualty reports were filed

within several days of the battle yet; there are reports of bodies being found and buried up to October 22nd, over two weeks after the battle. Also some that were listed as wounded died several days later from their wounds. Another complication was the two sides didn't use the same methods for daily accounting for their personnel. The Confederate casualty rates are very hard to determine. Several senior Confederate officers placed their losses between 1,500 and 2,000. Yet the official estimates of Confederate losses range from 799 to 897. This wide variance in numbers could be due to the fact that the wagons that the Confederates had planned to use in removing the supplies from Allatoona warehouses instead carried many of their wounded and killed from the battlefield. There were so many confederate wounded left on the battlefield that General French left some of his medical staff on the battlefield to care for the wounded that he couldn't take with him.

Here is some background of what happened before the battle of Allatoona Pass. Union General Sherman took Atlanta on Sept. 2nd, 1864 after defeating Confederate General Hood in a series of battles in and around Atlanta. With Sherman firmly in possession of Atlanta, Hood decided to move his troops to the north towards Chattanooga, with these goals in mind: Disrupt Sherman's supply and communication line on the Western and Atlantic Railroad (W&A RR) connecting Atlanta to Chattanooga, Force Sherman to backtrack on his North Georgia gains and to invade Tennessee. The battle of Allatoona Pass is considered by most to be the first battle in Hood's Nashville Campaign. This campaign was the last major Confederate Offense of the Civil War.

The strategic importance of the battle was the Union's defense of the W&A RR through a cut in the Allatoona Mountains range known as the Allatoona Pass. It was approximately 360 feet long, 175 feet deep and 60 feet wide. About 90 feet from the top on each side is a flat "berm" to catch falling rocks and such. The Pass was the deepest rail cut along the W&A between Atlanta and Chattanooga. Allatoona was also the intersection of the Tennessee Road and the old Alabama Road. The Alabama road is also called the Carterville Road on some maps. During his advance on Atlanta in June of 1864 General Sherman avoided the Allatoona Pass due to its defensive capabilities. After the Confederates had vacated the Pass, Sherman had his Engineers design a system of forts and trenches that would take full advantage of the Pass's natural strengths. The fortifications would not only protect the railroad, but also the supply depot at Allatoona. The supply depot at Allatoona was the Union's main supply depot south of Chattanooga. By the fall of 1864 the Warehouses at Allatoona contained at least one million rations of hardtack.

The fortifications at the pass had been designed to protect about 800 men. General French described the forts as having walls twelve foot thick, six foot high with a six foot ditches in front of them. The Star and Eastern Forts were about 75 ft. in diameter. Prior to the battle the pass was garrisoned by 966 men. The Garrison was manned by 280 men of the 93rd Illinois, 150 men of the 18th Wisconsin, 450 men of the 4th Minnesota, 15 men (a Detachment) of the 5th Ohio Cavalry and 71 men of the 12th Wisconsin Battery. The Garrison Commander was Lt. Col. John E. Tourtellotte. Tourtellotte was normally the commander of the 4th Minnesota, but as senior officer he was Garrison Commander prior to the battle and Major James C. Edson was the commander of the 4th Minnesota at the time of the battle.

Between October 3rd and 4th, Hoods forces tore up fifteen miles of track near Acworth/Big Shanty on the A&W RR south of Allatoona. This action served as the preliminary for the battle at Allatoona Pass that was to come. In response to Hood's movements, Sherman had sent General Corse and his division to defend Rome, GA and marched half of his army towards Marietta. By October 4th, Sherman had learned that 3,276 troops under Confederate General French were headed towards Allatoona Pass. There are different reports that state that Sherman couldn't have made it to Allatoona Pass in time to stop the Confederate attack due to the distance, but it's known that Sherman did know most of Hood's plans because they had been printed in southern Newspapers after President Davis made a speech to the Confederate troops that detailed the plans of the Campaign. It's never really been answered why Sherman wasn't in a position to stop Hood from attacking his supply line at Allatoona. What is known is that Sherman sent General Corse a message to move his Division from Rome to Allatoona Pass on October 4th, about a thirty mile trip by train. General Corse managed to ship 1,054 of his men from Rome to Allatoona Pass in time for the battle. However, the railroad transit had many difficulties:

"The train, in moving down to Rome, threw some fourteen or fifteen cars off the track, and threaten to delay us till the morning of the fifth, but the activity of the officers and railroad employees enabled me to secure a train of twenty cars about 7 p.m. of the 4th. Onto them I loaded three regiments of Colonel Rowett's brigade and a portion of the Twelfth Illinois Infantry, with about 165,000 rounds of ammunition, and started for Allatoona at 8:30 p.m., where we arrived at 1 a.m. on the morning of the 5th instant, immediately disembarked, and started the train back, with injunctions to get the balance of the brigade and as many of the next brigade as they could carry and return by day-light. They unfortunately met with an accident that delayed them so as to deprive me of any re-enforcements until about 9 p.m. on the 5th" (Official Report)

General French was ordered on October 4th to march on Allatoona Pass and fill the railroad cut, move on to the Etowah River and destroy the bridge there and then meet Hood at New Hope, GA. This would have been a difficult task for General French to have accomplished in the time allowed by Hood. To further complicate the mission the cut was heavily fortified on both sides, a fact that General French later pointed out was possibly unknown to his superiors and the task was almost impossible to accomplish. It also appears that General French was un-aware that that Allatoona Pass had been re-enforced with more troops. His local guide informed him that it was protected by three and a half regiments of infantry and four pieces of artillery. According to the memoirs of a soldier from the 93rd Illinois the troops at Allatoona Pass could hear the fighting going on to the south of them during the day of October 4th and they slept in the trenches and fortification with their weapon at ready the night of October 4th.

Lt. Colonel Tourtellotte wrote:

"My first unpleasant apprehensions were that the rebels would make a night attack, and taking advantage of the darkness depriving me of the advantage of position, the fortifications of this place all being on the high ridge while the stores are collected on the flat land at the hill's base and on the south side, from which direction the rebels were approaching. To prevent such approach I strengthened the grand guard, barricaded the roads to the south and made preparations to fire a building which should so illuminate the site of the village and stores that my men could see, even in the night, to a considerable extent any approach of the enemy. In this way I hoped to hold the rebels till daylight, when we should have the full advantage of our superior position.

About 12 midnight I was not a little relieved by the arrival of General Corse with one brigade, Fourth Division, Fifteenth Army Corps. About 2 a. m. of October 5th the rebels charged upon my picket-lines and drove the outposts back upon the reserves."

Note: Many stories of the battle give different times for events that happened. There are a number of reasons for this. During the battle you didn't have anyone recording the exact times that something happened, so times were recorded from memories and what the recorder of the event thought the time was. Very few of the higher ranking officers owned a watch much less junior officer or the enlisted. Then you also have the problem of different watches being set to different time. You didn't have a Radio, TV or Cell Phone to set your watch to. So if you had a watch it may have been set to some clock in a town that you passed thought or the guy next to you.

Starting around 7:00 a. m. the Confederates opened an 11 cannon artillery barrage on the fortified Union positions. According to the memoirs of the soldier from the 93rd Illinois this artillery barrage did very little damage and several of the Confederate guns were put out of commission by the Union guns and the Confederate guns were forced to withdraw out of range of the Union guns. According to the history of the 4th Minnesota there wasn't anyone injured or killed from this barrage, but it did kill all 27 horses of the 12th Wisconsin Battery. During this bombardment French continued to move his forces into position for attack, with General Young and General Cockrell to the west and General Sears to the northwest and north of the forts. No attacks came from the east due to the Allatoona River that was there and is now under Lake Allatoona. Sometime about 9:00 a.m. General French, thinking that he had the forts surrounded and significantly outnumbered sent an ultimatum to General Corse to surrender:

"SIR: I have placed the forces under my command in such position that you are surrounded and to avoid a needless effusion of blood, I call on you to surrender your forces at once and unconditionally. Five minutes will be allowed you to decide. Should you accede to this you will be treated in the most honorable manner as prisoners of war."

It is agreed upon by both side that French's message of surrender was received by General Corse. But from that point on it's another part of the legend and myths of the battle. General French said that he never got Corse's reply. It's not know if Major Sanders, who waited seventeen minutes for the message never received it, never gave it to French, left before the message was sent or if French's troops jumped the gun and started firing as soon as the Major returned to the Confederate lines and Major Sanders didn't feel the need to deliver the message to General French. Another thing that may have complicated things is that during this time under the white flag of truce that the confederates continued to advance and improve their positions prior to the battle in violation of the code of the truce. General Corse replied with the following answer:

"We are prepared for the ‘needless effusion of blood' whenever it is agreeable to you."

It isn't my intent in this story to tell all about the battle. While it's very interesting it's too long for this narrative.

This is a summation of the battle. Starting about 3:00 a.m. there were skirmishes between the two forces as the outer pickets met. The Union Troop fell back to their rifle pits and forts and the Confederate Troops advanced around Allatoona Pass taking positions on the south, west and the north sides of the pass. Depending on the report about 9:00 a.m. the fighting started after the Union was asked to surrender. By 11:00 the Union Troops in Rowett's redoubt to the west of the Star Fort and the outer trenches and rifle pits had been overtaken by Confederate forces. The Union forces still held both Forts and the trenches protecting both forts. Between 11:00 a.m. and some reports say 12:00 and others say 1:00 p.m. at least four assaults on the forts were made by the Confederates. At times the fighting in the trenches was hand to hand, but all the assaults were repulsed. Some reports state that the Union Troops were outnumbered four to one in some of these assaults.

About 11:00 a.m. General Course ordered the 12th and the 50th Illinois Regiments to the west side. But in the confusion the 57th Illinois Regiment also moved to the west side leaving the 4th Minnesota Regiment along with four companies of the 18th Wisconsin Regiment to man the east side of the pass.

There are stories of soldiers that had been wounded a number of times that kept fighting. Nearly every Field Grade (Major and above) Union Officer on the west side was wounded or killed during the battle rallying the troops. There was an account of a soldier on the east side with the 4th Minnesota that had an arm amputated and went back to the line to drag hundred pound boxes of ammunition to the troops still fighting. This man died a couple of days later due to blood poisoning.

The 7th Illinois Infantry had Henry repeating rifles, with a 16 shot magazine and they are one of the reason that the Union forces were able to withstand these Confederate assaults. These weapons had been purchased and shipped at the expense of Captain John Smith of the 7th Illinois Infantry. Another report stated that the men bought the Henry Rifles for themselves for $52 a person. These rifles had arrived just days before the battle. The Henry was a predecessor to the Winchester Rife and looked similar. This was the first time that many of the Confederate Troop had ever run into these weapons.

To increase the rate of fire in the Star Fort they had groups of three men working together. Two would load weapons and the third would fire. About 12:00 according to a soldier memoir from the 93rd Illinois and 2:30 according to General Course's report the Star Fort lost one of their Rodman artillery guns when a shell jammed in the barrel. Another artillery piece in the Star Fort had to be moved across the fort and into position to replace the disabled gun. There were so many wounded and dead within the fort that it took almost an hour to move and have the replacement gun ready to fire on the Confederate forces. During this time Confederate sharpshooters and troops were continually firing on the Star Fort from a nearby house and barn and from behind stumps making it nearly impossible for the men inside the Star Fort to return fire. The Star Fort did have a design flaw. The Union Troops had to expose themselves to fire over the top to return the Confederate fire. After the artillery piece was in place it was able to destroy the buildings and cover that the Confederates were using to fire on the Star Fort.

One story stated that the Confederate fire was so heavy that the artillery pieces had to be load by soldiers laying on the ground so as not to be shot during the loading and firing process. The Union artillery pieces were firing so fast and often that they began to overheat and they had to have time to cool off. The artillery pieces were firing loads of double grape or canisters of shot most of the time. Loading them this way made them the same as a very large shotgun. The artillery on the west side was going through so much ammunition that Edwin R. Fullington, a private of the Twelfth Wisconsin battery, crossed and re-crossed the narrow and rickety footbridge over the railroad cut three times, under direct fire from the enemy, and carried grape and canister ammunition from the Eastern Fort to the Western Fort. Many of the men of the Twelfth Wisconsin battery were killed trying to man and fire their pieces. One of the men manning the artillery in the Star Fort later received the Congressional Metal of Honor for his bravery during the battle. Prior to the battle the Twelfth Wisconsin Battery had received a new flag. This flag was located in the Western Fort during the battle. After the battle ended, there were one hundred and ninety-two bullet holes in that flag. It told the story of a terrible battle.

About 2:00 AM the fighting slowed. The Union Troops in the Star Fort were low on ammunition and the Confederate Troops weren't assaulting the Forts, but firing on them from cover. While most of the fighting was in the north-west, western and south-west sides of the pass the eastern side where Hans and the 4th Minnesota fought saw its share of battle also.

Here is an excerpt from the memoir of the same 93rd Illinois soldier.

"The fighting east of the railroad cut was the counterpart of that on the west side, except that it was less severe. On that side, also, two or three charges were attempted by the enemy, and repulsed; but the numbers of the assaulting forces there were much less than of those on the west side, the ascent to the fort and entrenchments was steeper, and the starting point was farther away. The Federal force there was only about one-half as great as that on the west side, but they were better distributed, and the fortifications were better and better located. Hence, the main attack and most of the vigorous fighting of the enemy was on the west side of the railroad cut. Nevertheless, that on the east side was quite severe, and was maintained with great persistency to the end. A part of the troops on the east side were so located that they could, and at times did, render valuable assistance to those on the west side. But the greater part of the time they had all they could reasonably be expected to attend to on their own side of the railroad. As a matter of fact, however, they attended to what they had to do there, and did it remarkably well, and still had a few spare moments in which they sent many whistling messengers to the enemy across the railroad. The last charge of the enemy on the east side of the railroad cut was made, a little before noon, by the Thirty-fifth and Thirty-ninth Mississippi regiments. They suffered heavy losses, and the large part of both regiments retired from the onset."

Some reports felt that the Confederates fought on after the last assault was defeated about noon in the hope they might capture the rations stored in the warehouses at Allatoona. French's men had brought two hundred wagons with them for this purpose. There are stories that General French had told his men that they would be eating the Unions Armies food by 10:00. After the battle it was found that many of the dead Confederate soldier knapsacks didn't have any provisions in them or they only contained ears of field corn with a pan with holes punched in them to grind the corn into corn meal. In retrospect one of the great failures of the Confederate attack was leaving the Federal supplies intact.

I have read several reasons why this happened. The following are the most common.