TALLADEGA COUNTY STEEPED IN HISTORY TOO, WILD WEST HAD NO LEASE ON INDIAN STORIES.

THE LIFE AND TIMES OF JOHN GARRISON HOSEY

WRITTEN BY JOE PATTON WITH J.E. (EUGENE) HOSEY AND JAMES PORTWOOD.

This Article was in the Sylacauga News on September 18, 1975, Page 2A

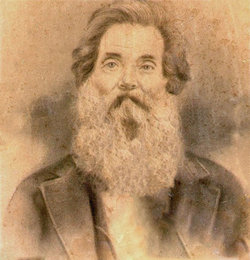

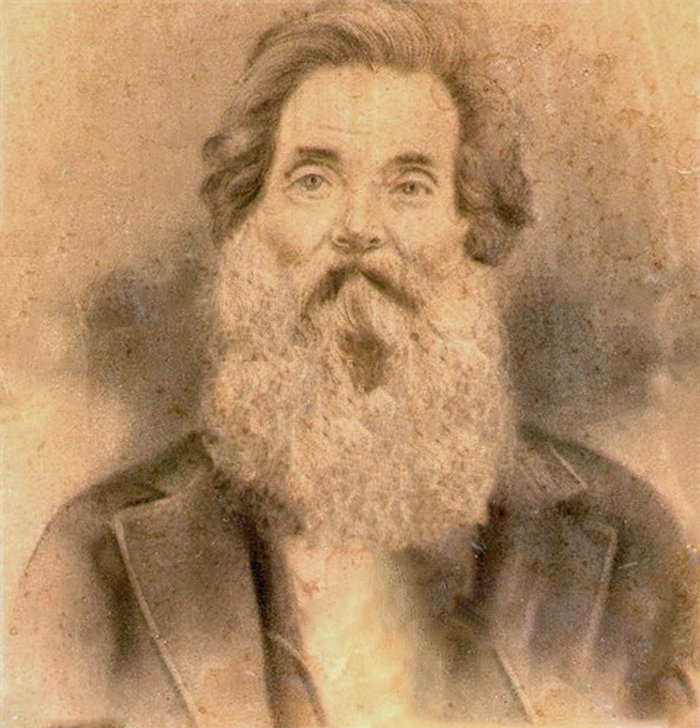

A MAN OF PIONEER STOCK

The rugged individualism of an early settler shows in the face of John Garrison Hosey (1810-1899) who lived a life of adventure among the Indians of early Talladega County before homesteading a property south Fayetteville of 200 acres. A lot of colorful accounts of those early days were handed down to future generations, within recent memory, by a son, Jess Hosey, who died at the pre-Civil War home place, where J.G. and Cleopatra (Meharg) Hosey reared fourteen children, in 1937. Among the descendants of this

grandson of Scottish immigrants who came here from St Clair County in his early 20's are grandsons W.O. Hosey of Sylavon Court and Allen Hosey of Five Points and great grandchildren Faye Hosey and J.E. (Eugene) Hosey of Sylacauga, to name merely a few. There are many interesting stories about the hearty stock that peopled this area and his is one of them.

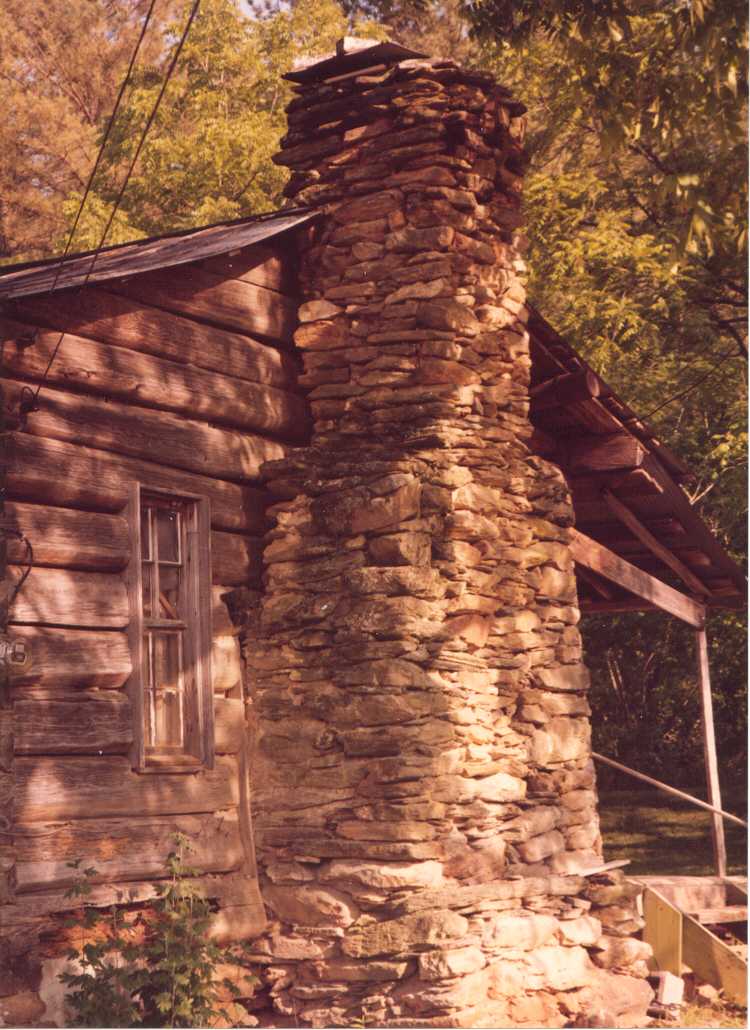

JOHN GARRISON'S HOME IN FAYETTEVILLE, TALLADEGA COUNTY, ALABAMA

The old Indian chief told young John Garrison Hosey that he had a dream in which Hosey made a gift of his rifle, a beautiful piece the Indian had his eye on for some time. Now the young man lived among the Indians, hunted with them, learned their language and to respect their customs. He knew better than to thwart that dream knowing the Indians were what some might call superstitious. So he reluctantly parted with the rifle which in the wilds of early Talladega County literally meant survival for a white man as yet relatively unskilled in the Indian ways of putting meat on the table, so to speak.

But later he got to thinking maybe he'd been hustled out of that rifle and hatched not only a scheme to get it back but a handsome hatchet to boot. "I had a dream the other night," Hosey began. He said that in the dream the old chief had not only returned the rifle but also made a gift of his hatchet. Without a word, the proud Indian compiled in all good faith. It was then that Hosey gained an even more healthy respect for his new friends. He had not been hustled at all; the old Indian really believed in dreams.

HISTORICAL NARRATIVES of those early days related to J.E. (Eugene) Hosey by the sons of his great grandfather during his childhood are as fresh in memory as if they had been told yesterday. The patriarch of the Hosey clan in that neck of the woods died shortly before the turn of the century, the last of the sons, Jesse Garrison Hosey, passing on at the old homestead about three and one half miles south of Fayetteville in 1937. Those stories tell us that the Wild West had no lease on Indian History, that in fact Talladega County, locale for several different tribes including the Creek linguistic group, one of the five civilized tribes, possesses as rich a past as any other area of the nation. A certain mysterious aura still hangs about the old Hosey place. History came alive, meaningful here Sunday afternoon, as if it were only yesterday. Artifacts found several hundred feet away in a field just off the banks of Peckerwood Creek substantiate stories that an Indian village indeed once lay just below the old log dwelling. Many of them long since gone, some along the "Trail of Tears" during the Indian removal, were numbered among John Garrison Hosey's good friends. A shaped green stone in proximity to other artifacts told a story itself. Indians had cultivated these fields long before the white man. A blade chipped on the stone's edge was still good. It was a perfect Indian hoe specimen. Hoes are seldom recovered in perfect condition.

HIGHLY UNUSUAL BURIALS found along a knoll across the creek several years ago lend merit to stories that Indian trials and executions were held there long ago. Indian collector James Portwood heard a strange tale about a drowning tree, which stood nearby, a big hardwood with a giant limb hanging out over the creek. Legend had it that conviction of a capital offense caused the criminal to be suspended from the limb by his feet and dunked into the creek until he was drowned. As a permanent mark of dishonor, the criminal was supposed to then be buried headfirst. Boyhood memories of what was reputed to be the drowning tree led Eugene Hosey to half believe the story while Portwood was a little skeptical about it because it sounded like some version of the Puritan punishment by dunking.

Skeletal remains which were plowed up along the knoll brought Portwood down for a look and what he found left him pretty much convinced about the truth of the tale. What happened to be a fire pit, a round hole, held a skeleton which had been placed in a deed pit head first, unlike anything Portwood had seen in years of artifact hunting which had taken him to sites all over this and surrounding counties. Unlike other burials, the Indian had been interred without any of his possessions, also highly unusual--no beads, no bracelet, no medallion, nothing. Several other burials, which were plowed into on that one knoll over the years, bore the same mute testament. "It's something I've not come across anywhere else, before of since, "Portwood says. "And I don't know anybody who has."

OLD FAMILY ACCOUNTS suggested that the executed Indians weren't the only ones buried in disgrace on the grounds of the old Hosey place, nor theirs the only trial. It seems that back in the early 1830's before the Indian removal that one character known simply as Spraggins was given to promoting ticklish situations by selling or trading firewater to Indians from the villages along the Hooksgulee (Peckerwood) Creek to the chagrin of both responsible Indians and whites.

The story had it that some angry whites caught old Spraggins at his whiskey still on Stillhouse Branch (that's how it got its name) and held a trial of their own. They were supposed to have torn out the still worm and meted out some punishment to the whiskey maker who came up missing. Nobody knows for sure whether John Garrison Hosey had anything to do with it, but it appears he knew who did.

Back around 1900, one of his sons, Clint Hosey, plowed up part of a jawbone upstream from the still site. He remarked that it was bound to be old Spraggins because his father had said that Spraggins had been buried near there many years ago. Some twenty-three years later, Jesse Hosey plowed up part of the still worm near the same spot. The three of us trekked through the hill beyond the Hosey place Sunday afternoon in search of the remains of the still that Eugene Hosey remembered for some forty-five years back. We found it upstream from the juncture of Stillhouse Branch and Peckerwood Creek just off an old road, which wound from the homestead across the branch to join Marble Valley Road several miles beyond. The old road had been overgrown for years, but the wagons had left their indelible mark in the terrain.

A rock wall built around the still pit has long since crumbled and the cooking pit filled in for the most part, but the telltale signs were still recognizable after all these years. Spraggins had built a shelter over the still, hence the name "stillhouse, " and carried water for making the whiskey from the crystal clear branch about 20 yards away. It was pretty evident that he dipped his water from a pothole about three feet deep. It's not hard to visualize why justice may have fallen rather heavy handed with old Spraggins in those precarious times when a whiskey runner would be as popular as a drug pusher. They wreaked their own sort of havoc, too, even injury and death.

The rascally whiskey peddler may not have had far to go for his first firewater stop because the level flats on the other side of the creek several hundred yards off may have supported a fairly sizable Indian village.

If he'd known about it, he might have tried to worm the Indians out of some information.

Like many other locales, the old Hosey place abounds in tales of a rich mineral strike. Tales about U.S. Grant Hosey's making a strike isn't too far removed from recent memory. "Well, here's where Carson made another ‘pit stop'," Portwood said. Numerous diggings pockmarked the base of a hill above the branch and upstream along Peckerwood Creek almost to the old home, about two miles worth.

Grant was supposed to have sent an ore sample off to a New York company for analysis and it assayed high-grade platinum. In course of negotiating an agreement, so the story goes, the company tried to threaten legal action to make Grant tell the strike's location. The by now distrusting Grant simply clamed up and vowed that they or nobody else would ever find it. Nobody ever did.

Apparently, Carson Lawrence, who had prospected in Colorado at one time, believed there was truth to the story and set out to find it. Portwood had accompanied him on two or three trips, but even he was surprised at the extent of the quest. Working with a pick and shovel and wheelbarrow, Lawrence turned a considerable amount of dirt but as far as anybody knows never found the secret that Grant Hosey was supposed to have carried to his grave.

AN ADVENTUROUS LIFE awaited John Garrison Hosey when in his early twenties he left St. Clair County to make life here. It is known that he arrived around Fayetteville sometime around 1832 and ranged from Fayetteville to Talladega Springs among the Indians until their relocation out west about four years later. Except for an Indian friend's advice, he might not have arrived long enough to settle down, although there were undoubtedly other close calls.

While taking a trail back from a trip up near Sylacauga way, he came across the outskirts of a large Indian encampment but before going in was warned there were a lot of mean Indians in there and to steer clear. Hosey said that he wasn't afraid since he had good relations with the Indians but his friend admonished him to bypass it since he might be killed if he went in. Presumably, there were Indians as far away as Georgia in the large band that was massing for the move out of their homeland.

Pines in a grove about an acre in extent were blazed with axes as far up as the Indians could reach, giving it the name "Skinned Pines." "The trees are probably gone now, but I saw them many times when I was a boy," Eugene Hosey recalls.

The first large groups of Indians were taken across the Coosa River at Brasher's Ferry, west of the Blue Springs community. John Garrison told his children in later years that he had gone down to see many of his friends for the last time, and was left with a heavy heart. One of his dearest friends, old Chief Yellowhammer, flatly refused to leave and lay in his hut at the foot of Goodman Hill, refusing food or drink, until he withered away and died.

From the late 1830's until some time before the Civil War or just after, Hosey floated barges on the Childersburg to Wetumpka and Montgomery run. River pilots during that era were lashed together heavy for a barge and sold the timber for what they could get when they reached their destination with the cotton. Sometimes, he would be gone weeks at a time because not only was the trip long and treacherous, but the pilot walked back. A railroad route from Mobile to Childersburg did away with most of the river shipping. A launch site for the barges, which were operated largely by independents, was located on the Tallaseehatchie Creek near what is now the Plant Road Bridge.

HOSEY HOMESTEADED about 200 acres and married Cleopatra Meherg when he was thirty-four years of age. She was in her early twenties. The union proved quite fruitful, fourteen children issuing from the marriage. The first home was built about three-fourths of a mile upstream from the present site, but Hosey and his wife lived there only a few years before building another. Nobody can date the second, but it is known that it predates the Civil War by a number of years. The second home was constructed of heavy, hand hewed logs and it had a dogtrot, which was later enclosed. Later additions of sawed lumber as the family grew suggest that most of the children were born in the second home.

A fervently patriotic Hosey named sons after George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Andrew Jackson, and the youngest after U.S. Grant. Now, naming a son after Grant might not sound the ultimate in patriotism to some southerners, but it's quite possible that Hosey may have done it just to vex some prominent "night riders" form the Fayetteville district who had once threatened his life. The same four men were supposed to have killed another, Elisha Wood, because he was not in sympathy with slavery and the free-spirited Hosey didn't cotton to it too much, either.

It appears that Elisha Wood made no secret about a distaste for the institution on ethical and moral grounds and that was enough to rile some folks itself, sort of like "if'n you ain't fer us, then yer agin us." A tombstone over his grave in Rehobeth Cemetery off Jennings Road records the essential facts of the incident except the names of those who did the deed.

Hosey probably got off on the wrong foot with a few folks in the area when he returned a little Negro boy he'd been given in settlement of a debt. He reluctantly took the boy, but thinking how the mother had cried for the little fellow was filled with remorse and turned around before he even got home. He released the child to the mother and bound the startled, perhaps angry gent who had settled the debt in such manner to never separate the child from his mother because he no longer had that right. The account has it that right after Wood's death; the night riding quartet paid Hosey a little visit with the intention of killing him. Hosey, a man known not to mince words, told the four they might do it but that they could be assured two of them were going to make the trip, too. Nobody was willing to be the one of the two and that apparently ended the attempt to purge the area of anti-slavery blood. A lot of southerners that weren't pro-slavery fought under the Confederate flag and intensely loyal Hosey would have probably left his family if he'd been asked to but never was called. His eldest was twelve when the Civil War broke out.

A lot of others fought under the Union banner on the pretext of abolishing slavery, but history shows there were also a number of other cases for the prohibitively costly war, in terms of economy and lives, which might have been peacefully resolved had cooler head prevailed. Although many may be under the illusion that the Emancipation Proclamation abolished what was recognizably an evil institution to begin with, that slavery was not totally abolished in some Union Border States until well over twenty years after the war. Like a lot of folks left holding worthless Confederate bonds and securities, Hosey, once fairly comfortable, lost virtually everything he had and never quite recovered financially.

ONE OF HIS CHILDREN might have made a fortune in the hands of a skilled showman like P.T. Barnum but it undoubtedly would have gone against the family's grain to even consider such a thing. Not unlike Charles Stratton's (Tom Thumb) wife, Lavenia, Sallie Chilona Hosey was a highly intelligent, beautifully well proportioned woman just 32 inches tall. She reportedly weighed 32 pounds, had hair 32 inches long, and died at age thirty-two. Her tiny chair", was a treasured family possession for many years.

Another branch of the Hosey family, including John Garrison's father, Jesse (born 1789) relocated from St. Clair County and settled at Talladega Springs sometime after the Indian Removal. The descendants can trace their origins in this country to one John Davidson Hosey, a Scot immigrant who was reared in North Carolina by a man named Autry sometime in the 1750's. He would have been John Garrison's grandfather.

It is believed that both parents died while crossing the Atlantic and that Autry took them in rather than see the boys left destitute. It is said that one man wanted to adopt the boys but that Autry thought it would be wrong to deprive them of that birthright and while rearing them as his own left them with their rightful surnames.

Only a genealogical search would reveal precisely where in Scotland the family originated, but some light may have been shed by a visitor to Kimberly-Clark, a Scotsman, who spied J.E. Hosey's name on a tool box and asked if Hosey's ancestor's had come from Scotland. Told they had, the visitor said that he knew many Hoseys around Edinburgh and conjectured they probably came from that area.

A plausible explanation is that the Hosey forebearers probably left after the highland clans rallied under the banner of Bonnie Prince Charlie in 1745. A search of the archives at Edinburgh Castle several years ago revealed that the actual origins of the Hosey family in the old world may remain shrouded in the distant past, but it is known that one of them, John Garrison Hosey, helped write a colorful chapter of local history in another time and place.

The diary of Egbert Waters records that Hosey, who was amazingly active in his last years, died June 6, 1899 at his home in his 89th year.

Note: According to family records, Cleopatra and John Garrison Hosey along with other family members are buried at Holly Springs Cemetery in unmarked graves.

TALLADEGA COUNTY STEEPED IN HISTORY TOO, WILD WEST HAD NO LEASE ON INDIAN STORIES.

THE LIFE AND TIMES OF JOHN GARRISON HOSEY

WRITTEN BY JOE PATTON WITH J.E. (EUGENE) HOSEY AND JAMES PORTWOOD.

This Article was in the Sylacauga News on September 18, 1975, Page 2A

A MAN OF PIONEER STOCK

The rugged individualism of an early settler shows in the face of John Garrison Hosey (1810-1899) who lived a life of adventure among the Indians of early Talladega County before homesteading a property south Fayetteville of 200 acres. A lot of colorful accounts of those early days were handed down to future generations, within recent memory, by a son, Jess Hosey, who died at the pre-Civil War home place, where J.G. and Cleopatra (Meharg) Hosey reared fourteen children, in 1937. Among the descendants of this

grandson of Scottish immigrants who came here from St Clair County in his early 20's are grandsons W.O. Hosey of Sylavon Court and Allen Hosey of Five Points and great grandchildren Faye Hosey and J.E. (Eugene) Hosey of Sylacauga, to name merely a few. There are many interesting stories about the hearty stock that peopled this area and his is one of them.

JOHN GARRISON'S HOME IN FAYETTEVILLE, TALLADEGA COUNTY, ALABAMA

The old Indian chief told young John Garrison Hosey that he had a dream in which Hosey made a gift of his rifle, a beautiful piece the Indian had his eye on for some time. Now the young man lived among the Indians, hunted with them, learned their language and to respect their customs. He knew better than to thwart that dream knowing the Indians were what some might call superstitious. So he reluctantly parted with the rifle which in the wilds of early Talladega County literally meant survival for a white man as yet relatively unskilled in the Indian ways of putting meat on the table, so to speak.

But later he got to thinking maybe he'd been hustled out of that rifle and hatched not only a scheme to get it back but a handsome hatchet to boot. "I had a dream the other night," Hosey began. He said that in the dream the old chief had not only returned the rifle but also made a gift of his hatchet. Without a word, the proud Indian compiled in all good faith. It was then that Hosey gained an even more healthy respect for his new friends. He had not been hustled at all; the old Indian really believed in dreams.

HISTORICAL NARRATIVES of those early days related to J.E. (Eugene) Hosey by the sons of his great grandfather during his childhood are as fresh in memory as if they had been told yesterday. The patriarch of the Hosey clan in that neck of the woods died shortly before the turn of the century, the last of the sons, Jesse Garrison Hosey, passing on at the old homestead about three and one half miles south of Fayetteville in 1937. Those stories tell us that the Wild West had no lease on Indian History, that in fact Talladega County, locale for several different tribes including the Creek linguistic group, one of the five civilized tribes, possesses as rich a past as any other area of the nation. A certain mysterious aura still hangs about the old Hosey place. History came alive, meaningful here Sunday afternoon, as if it were only yesterday. Artifacts found several hundred feet away in a field just off the banks of Peckerwood Creek substantiate stories that an Indian village indeed once lay just below the old log dwelling. Many of them long since gone, some along the "Trail of Tears" during the Indian removal, were numbered among John Garrison Hosey's good friends. A shaped green stone in proximity to other artifacts told a story itself. Indians had cultivated these fields long before the white man. A blade chipped on the stone's edge was still good. It was a perfect Indian hoe specimen. Hoes are seldom recovered in perfect condition.

HIGHLY UNUSUAL BURIALS found along a knoll across the creek several years ago lend merit to stories that Indian trials and executions were held there long ago. Indian collector James Portwood heard a strange tale about a drowning tree, which stood nearby, a big hardwood with a giant limb hanging out over the creek. Legend had it that conviction of a capital offense caused the criminal to be suspended from the limb by his feet and dunked into the creek until he was drowned. As a permanent mark of dishonor, the criminal was supposed to then be buried headfirst. Boyhood memories of what was reputed to be the drowning tree led Eugene Hosey to half believe the story while Portwood was a little skeptical about it because it sounded like some version of the Puritan punishment by dunking.

Skeletal remains which were plowed up along the knoll brought Portwood down for a look and what he found left him pretty much convinced about the truth of the tale. What happened to be a fire pit, a round hole, held a skeleton which had been placed in a deed pit head first, unlike anything Portwood had seen in years of artifact hunting which had taken him to sites all over this and surrounding counties. Unlike other burials, the Indian had been interred without any of his possessions, also highly unusual--no beads, no bracelet, no medallion, nothing. Several other burials, which were plowed into on that one knoll over the years, bore the same mute testament. "It's something I've not come across anywhere else, before of since, "Portwood says. "And I don't know anybody who has."

OLD FAMILY ACCOUNTS suggested that the executed Indians weren't the only ones buried in disgrace on the grounds of the old Hosey place, nor theirs the only trial. It seems that back in the early 1830's before the Indian removal that one character known simply as Spraggins was given to promoting ticklish situations by selling or trading firewater to Indians from the villages along the Hooksgulee (Peckerwood) Creek to the chagrin of both responsible Indians and whites.

The story had it that some angry whites caught old Spraggins at his whiskey still on Stillhouse Branch (that's how it got its name) and held a trial of their own. They were supposed to have torn out the still worm and meted out some punishment to the whiskey maker who came up missing. Nobody knows for sure whether John Garrison Hosey had anything to do with it, but it appears he knew who did.

Back around 1900, one of his sons, Clint Hosey, plowed up part of a jawbone upstream from the still site. He remarked that it was bound to be old Spraggins because his father had said that Spraggins had been buried near there many years ago. Some twenty-three years later, Jesse Hosey plowed up part of the still worm near the same spot. The three of us trekked through the hill beyond the Hosey place Sunday afternoon in search of the remains of the still that Eugene Hosey remembered for some forty-five years back. We found it upstream from the juncture of Stillhouse Branch and Peckerwood Creek just off an old road, which wound from the homestead across the branch to join Marble Valley Road several miles beyond. The old road had been overgrown for years, but the wagons had left their indelible mark in the terrain.

A rock wall built around the still pit has long since crumbled and the cooking pit filled in for the most part, but the telltale signs were still recognizable after all these years. Spraggins had built a shelter over the still, hence the name "stillhouse, " and carried water for making the whiskey from the crystal clear branch about 20 yards away. It was pretty evident that he dipped his water from a pothole about three feet deep. It's not hard to visualize why justice may have fallen rather heavy handed with old Spraggins in those precarious times when a whiskey runner would be as popular as a drug pusher. They wreaked their own sort of havoc, too, even injury and death.

The rascally whiskey peddler may not have had far to go for his first firewater stop because the level flats on the other side of the creek several hundred yards off may have supported a fairly sizable Indian village.

If he'd known about it, he might have tried to worm the Indians out of some information.

Like many other locales, the old Hosey place abounds in tales of a rich mineral strike. Tales about U.S. Grant Hosey's making a strike isn't too far removed from recent memory. "Well, here's where Carson made another ‘pit stop'," Portwood said. Numerous diggings pockmarked the base of a hill above the branch and upstream along Peckerwood Creek almost to the old home, about two miles worth.

Grant was supposed to have sent an ore sample off to a New York company for analysis and it assayed high-grade platinum. In course of negotiating an agreement, so the story goes, the company tried to threaten legal action to make Grant tell the strike's location. The by now distrusting Grant simply clamed up and vowed that they or nobody else would ever find it. Nobody ever did.

Apparently, Carson Lawrence, who had prospected in Colorado at one time, believed there was truth to the story and set out to find it. Portwood had accompanied him on two or three trips, but even he was surprised at the extent of the quest. Working with a pick and shovel and wheelbarrow, Lawrence turned a considerable amount of dirt but as far as anybody knows never found the secret that Grant Hosey was supposed to have carried to his grave.

AN ADVENTUROUS LIFE awaited John Garrison Hosey when in his early twenties he left St. Clair County to make life here. It is known that he arrived around Fayetteville sometime around 1832 and ranged from Fayetteville to Talladega Springs among the Indians until their relocation out west about four years later. Except for an Indian friend's advice, he might not have arrived long enough to settle down, although there were undoubtedly other close calls.

While taking a trail back from a trip up near Sylacauga way, he came across the outskirts of a large Indian encampment but before going in was warned there were a lot of mean Indians in there and to steer clear. Hosey said that he wasn't afraid since he had good relations with the Indians but his friend admonished him to bypass it since he might be killed if he went in. Presumably, there were Indians as far away as Georgia in the large band that was massing for the move out of their homeland.

Pines in a grove about an acre in extent were blazed with axes as far up as the Indians could reach, giving it the name "Skinned Pines." "The trees are probably gone now, but I saw them many times when I was a boy," Eugene Hosey recalls.

The first large groups of Indians were taken across the Coosa River at Brasher's Ferry, west of the Blue Springs community. John Garrison told his children in later years that he had gone down to see many of his friends for the last time, and was left with a heavy heart. One of his dearest friends, old Chief Yellowhammer, flatly refused to leave and lay in his hut at the foot of Goodman Hill, refusing food or drink, until he withered away and died.

From the late 1830's until some time before the Civil War or just after, Hosey floated barges on the Childersburg to Wetumpka and Montgomery run. River pilots during that era were lashed together heavy for a barge and sold the timber for what they could get when they reached their destination with the cotton. Sometimes, he would be gone weeks at a time because not only was the trip long and treacherous, but the pilot walked back. A railroad route from Mobile to Childersburg did away with most of the river shipping. A launch site for the barges, which were operated largely by independents, was located on the Tallaseehatchie Creek near what is now the Plant Road Bridge.

HOSEY HOMESTEADED about 200 acres and married Cleopatra Meherg when he was thirty-four years of age. She was in her early twenties. The union proved quite fruitful, fourteen children issuing from the marriage. The first home was built about three-fourths of a mile upstream from the present site, but Hosey and his wife lived there only a few years before building another. Nobody can date the second, but it is known that it predates the Civil War by a number of years. The second home was constructed of heavy, hand hewed logs and it had a dogtrot, which was later enclosed. Later additions of sawed lumber as the family grew suggest that most of the children were born in the second home.

A fervently patriotic Hosey named sons after George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Andrew Jackson, and the youngest after U.S. Grant. Now, naming a son after Grant might not sound the ultimate in patriotism to some southerners, but it's quite possible that Hosey may have done it just to vex some prominent "night riders" form the Fayetteville district who had once threatened his life. The same four men were supposed to have killed another, Elisha Wood, because he was not in sympathy with slavery and the free-spirited Hosey didn't cotton to it too much, either.

It appears that Elisha Wood made no secret about a distaste for the institution on ethical and moral grounds and that was enough to rile some folks itself, sort of like "if'n you ain't fer us, then yer agin us." A tombstone over his grave in Rehobeth Cemetery off Jennings Road records the essential facts of the incident except the names of those who did the deed.

Hosey probably got off on the wrong foot with a few folks in the area when he returned a little Negro boy he'd been given in settlement of a debt. He reluctantly took the boy, but thinking how the mother had cried for the little fellow was filled with remorse and turned around before he even got home. He released the child to the mother and bound the startled, perhaps angry gent who had settled the debt in such manner to never separate the child from his mother because he no longer had that right. The account has it that right after Wood's death; the night riding quartet paid Hosey a little visit with the intention of killing him. Hosey, a man known not to mince words, told the four they might do it but that they could be assured two of them were going to make the trip, too. Nobody was willing to be the one of the two and that apparently ended the attempt to purge the area of anti-slavery blood. A lot of southerners that weren't pro-slavery fought under the Confederate flag and intensely loyal Hosey would have probably left his family if he'd been asked to but never was called. His eldest was twelve when the Civil War broke out.

A lot of others fought under the Union banner on the pretext of abolishing slavery, but history shows there were also a number of other cases for the prohibitively costly war, in terms of economy and lives, which might have been peacefully resolved had cooler head prevailed. Although many may be under the illusion that the Emancipation Proclamation abolished what was recognizably an evil institution to begin with, that slavery was not totally abolished in some Union Border States until well over twenty years after the war. Like a lot of folks left holding worthless Confederate bonds and securities, Hosey, once fairly comfortable, lost virtually everything he had and never quite recovered financially.

ONE OF HIS CHILDREN might have made a fortune in the hands of a skilled showman like P.T. Barnum but it undoubtedly would have gone against the family's grain to even consider such a thing. Not unlike Charles Stratton's (Tom Thumb) wife, Lavenia, Sallie Chilona Hosey was a highly intelligent, beautifully well proportioned woman just 32 inches tall. She reportedly weighed 32 pounds, had hair 32 inches long, and died at age thirty-two. Her tiny chair", was a treasured family possession for many years.

Another branch of the Hosey family, including John Garrison's father, Jesse (born 1789) relocated from St. Clair County and settled at Talladega Springs sometime after the Indian Removal. The descendants can trace their origins in this country to one John Davidson Hosey, a Scot immigrant who was reared in North Carolina by a man named Autry sometime in the 1750's. He would have been John Garrison's grandfather.

It is believed that both parents died while crossing the Atlantic and that Autry took them in rather than see the boys left destitute. It is said that one man wanted to adopt the boys but that Autry thought it would be wrong to deprive them of that birthright and while rearing them as his own left them with their rightful surnames.

Only a genealogical search would reveal precisely where in Scotland the family originated, but some light may have been shed by a visitor to Kimberly-Clark, a Scotsman, who spied J.E. Hosey's name on a tool box and asked if Hosey's ancestor's had come from Scotland. Told they had, the visitor said that he knew many Hoseys around Edinburgh and conjectured they probably came from that area.

A plausible explanation is that the Hosey forebearers probably left after the highland clans rallied under the banner of Bonnie Prince Charlie in 1745. A search of the archives at Edinburgh Castle several years ago revealed that the actual origins of the Hosey family in the old world may remain shrouded in the distant past, but it is known that one of them, John Garrison Hosey, helped write a colorful chapter of local history in another time and place.

The diary of Egbert Waters records that Hosey, who was amazingly active in his last years, died June 6, 1899 at his home in his 89th year.

Note: According to family records, Cleopatra and John Garrison Hosey along with other family members are buried at Holly Springs Cemetery in unmarked graves.

Family Members

-

Stephen William Hosey

1807–1882

-

Melissa Brasher Hosey Hawkins

1813–1886

-

James Brasher Hosey

1815–1880

-

Delila Jane Hosey Favor

1818–1880

-

Elizabeth Hosey Pearson

1819–1885

-

Judith Hosey Meharg

1825–1892

-

Ann H Hosey Pearson

1826 – unknown

-

Louisa Hosey

1828–1885

-

John Cicero Hosey

1829–1849

-

![]()

Johnathan Hawkins Hosey

1833–1891

-

Missouri Ann Hosey

1845–1918

-

Cleopatra H. Hosey

1846–1860

-

![]()

Thelbert Hawkins Hosey

1850–1918

-

![]()

John Clinton "Clint" Hosey

1853–1919

-

![]()

Jesse Garrison Hosey

1855–1936

-

![]()

Sallie Chelona Hosey

1858–1892

-

![]()

William Franklin Hosey

1860–1941

-

Andrew Jackson "Jack" Hosey

1862–1941

-

Harriett Jeanette Hosey Brazier

1864–1916

-

Ginnady Nadie Hosey

1867–1936

-

![]()

Jonathan Ulysses Grant Hosey

1869–1934

-

George Washington Hosey

1872 – unknown

-

Joseph Akins Hosey

1874–1888

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

Advertisement