by Michael A. Apgar, November 12, 2000

Wylie Hamby (nee "Wiley") was born between 1830 and 1836 in either Caldwell County, Yadkin County, or Asheville, North Carolina. (based on three conflicting references.) He was the oldest son of Martin Hamby and his wife Elizabeth Wells who married August 9, 1832. Wiley's father died when he was still an adolescent, leaving his mother with five young children. Wiley probably never knew when he was born. His mother was reportedly either blind, deaf or senile, helping to account for confusion about when Wiley was born. It also suggests that she would have been incapable of raising children on her own. This may explain the following line found in the Caldwell County (NC) records: "1850 January Term: Sheriff to bring orphan children of Martin Hamby deceased: Wiley, William and James".

Wiley's name appears on the 1852 tax list for Caldwell County, NC: "Hamby, Wiley, no land, 1 white poll". This indicates that he should have been 21 years old (which would make his birth in 1830).

Wiley married Martha Jane Mays (or Mayes) in Caldwell County on May 22, 1856. Martha Jane was born in 1840 or 1841. She was the oldest child of Morgan M. and Nancy (Day) Mays. The 1860 Caldwell County Census (taken July 28, 1860) includes, under "Buffalo District": "W.A. Hamby, 24, farmer, no real estate, personal estate $20, born in North Carolina, can't read and write, and in his household is Jane Hamby, 19, female, white, and Lucinda Hamby, 1, female, white." Wiley and Martha Jane also had a son, James, born about 1861.

The ‘War for Southern Independence' was nearly a year old, when Wiley enlisted as a private in Company A of the 22nd North Carolina Infantry, Volunteers for a term of three years. He was then 26 years old. His mustering in took place on March 19, 1862, at Lenoia, North Carolina.

The regiment had been organized immediately after hostilities began in April 1861. It was already in the field in Virginia. Wiley traveled there and took his place in the ranks as a new recruit.

James M. Hamby, who may have been Wiley's brother, had enlisted in the same unit when it was originally formed. James was 21 years old at the time. He also came from Caldwell County, North Carolina.

Apparently James got sick shortly after his army debut. Company returns identify him as a "nurse in hospital" in September 1861. (Typically nurses were soldiers who had entered the hospital as patients and were sufficiently recovered to help, but not so when they were fit for return to their units.)

Wiley must have fallen victim to disease too. His name appears on the role of Chimborazo Hospital No. 5 in Richmond on May 12, 1862 with the notation "diarrhea". He made a relatively rapid recovery, because on May 18th he was "sent to Camp Winder".

A pay statement in James' file indicates that he was paid $11/month for the three month period of June, July and August 1862. This was the standard pay for a private in the Confederate Army.

James Hamby was still in the hospital "Chirborazo Richmond No. 4" on October 28h 1862. The record indicates that he stayed there until February 6h 1863. By that time, the 22nd North Carolina was a veteran regiment in General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia.

The 22nd North Carolina suffered heavy casualties on the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg, July 1, 1863, in the fighting for MacPherson's Ridge, northwest of the town. On the third day of the battle, the regiment was part of General Pettigrew's command, which participated in the major frontal assault on the Union line on Cemetery Ridge which is known as "Pickett's Charge". The 22nd North Carolina was in the division temporarily commanded by James Lane, in the brigade commanded by Colonel Loughran. It assaulted the position just west of Cemetery Hill, which was held by the 10th Connecticut, the 1st Delaware and the 11th New Jersey. Confederate soldiers pressed forward into a hailstorm of Union artillery and concentrated rifle fire. Losses were extremely heavy, including 30 stands of colors (regimental flags). Many of the flags were lost, because they were carried in advance of the troops and casualties were so heavy that no one was able to bring them off the field.

There are no surviving muster cards to indicate whether Wiley and James were present with their regiment during most of 1863. However, a muster card for July & August 1864 notes that James was "captured July 3d 1863 at Gettysburg". James' name does not appear with those of Confederate prisoners taken to Fort Delaware, so the wound he received may have been mortal. A Roll of Honor card in Wiley's file (possibly for 1863, based on the sequence in which this record appears on the microfilm) indicates that he was "slightly wounded". However, the date, place and nature of the wound are not specified.

Wiley Hamby, a future member of the Apgar Family, may have been a participant in "Pickett's Charge", perhaps the most famous clash of the, Civil War. Ironically, although at least 150 Apgar family members served in the ranks of the Union Army, none of them were present at this point of this most famous struggle. Thus, the sole Apgar family participant in this storied event may have been a Confederate!

It is uncertain when Wiley was promoted to Corporal. Certainly the losses in the regiment created opportunities for promotion. At any rate, company muster rolls for July & August and September & October 1864 indicate that "W.A. Hamby, 2nd Corpl, CoA 22nd NC Infy" was "present".

Wiley's name also appears on receipt rolls for clothing on March 20th, April 3rd, November 5th, November 14th, and November 2nd 1864. Therefore, it seems that, except for his hospitalization for disease immediately after enlisting and some period of recuperation after he was wounded, Wiley must have served continuously with the 22nd North Carolina Infantry from the time of his enlistment until almost the end of the war.

A register of prisoners, dated March 7, 1865 for the Union Army of the Potomac includes "W.A. Hamby, CpL 22 NC-Co H" as a "Rebel Deserter". In the space for "Arms received", there is a notation "M. E.", which may stand for "musket, Enfield".

At the time Wily finally decided to throw in the towel the Confederacy was clearly on its last legs. General Grant had bottled up the remnants of the Army of Northern Virginia at Richmond and Petersburg. The Confederates were in the last days of a siege, which they could not break. General Sherman, whose destructive March to the Sea had split the Confederacy, was moving northward through the Carolinas. In a matter of weeks, the Confederate Capital would fall and the Confederate -cause would be lost. Thus, impending defeat, rather than disillusionment with "The Cause" would seem to have been Wiley's motivation for surrender.

Wylie's name also appears on another form, "Register of Rebel deserters, Provost Marshall General Wash, DC". This one includes "Sent from Army of Potomac, Taken oath trans. furnished to Oil City PA". This may have been a transfer to a temporary holding place for prisoners, with the end of the war at hand and the other prisons overcrowded. Perhaps since he voluntarily left the Confederate Army and took an oath of allegiance to the United States, Wylie was at liberty. At any rate, it helps to explain Wylie's presence in west-central Pennsylvania before the war officially ended.

When Wiley left the Confederate army, he also changed his name to Wylie (never using Wiley again) and deserted his family in North Carolina. His first wife, Martha, raised their son, James, who later married and had a family of his own. Wiley and Martha's daughter, Lucinda, did not survive to adulthood. In a letter dated January 7, 1892, Wylie's mother-in-law wrote: "My oldest child's name is Martha Jane ... Martha married Wiley Hamby and had two children. He went to the war in '61 and a few days before the war stopped he went over to the federal army and has never come back. " In 1920, Martha was still alive at the age of 82, and living with her widowed sister, Sarah.

Wylie settled in Williamsport, PA. According to his obituary (which is loaded with fanciful material, including claims that he had been a member of a prominent slave-owning family and had been a Confederate officer), Wylie first took a job at a local lumber mill. Shortly after the war he embarked in farming and lumbering in Lycoming County. There, Wylie married Rebecca C. Apgar (10.1.2.9.), the daughter of John S. and Jane (Clendenin) Apgar. Rebecca had been born in Lycoming County on December 27, 1845. Two of Rebecca's brothers were veteran's of the Union Army.

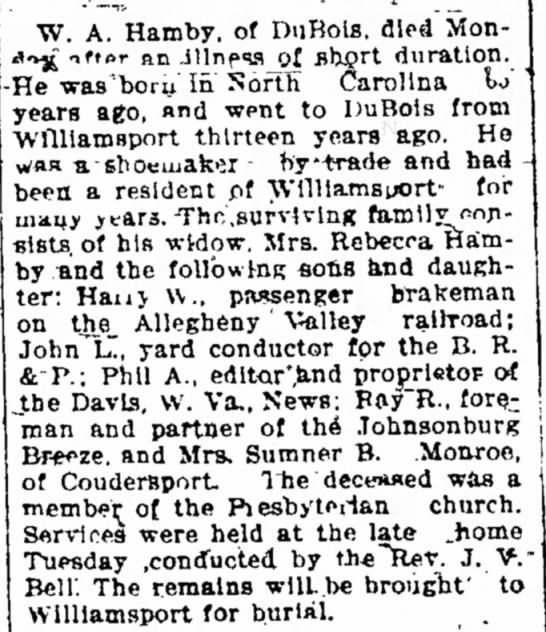

In 1888 Wylie and Rebecca, with their 4 sons and a daughter, moved to DuBois, Pennsylvania. There, Wylie worked as a shoemaker until the time he died in May 1901. He was a prominent and active member of the Presbyterian Church, and was reportedly "well known and highly respected, and his death is generally regretted". Wylie was buried in Trout Run, near Williamsport, his former home.

Wylie and Rebecca's children attended Wylie's funeral. They included: Harry W. Hamby, a passenger brakeman on the Allegheny Valley Railroad; John L. Hamby, a yard conductor for the Buffalo, Rochester and Pittsburgh Railroad; Philip A. Hamby, editor of the Davis (W.Va.) News; Ray R. Hamby, foreman and part owner of the Johnsonbury Breeze, and Mrs Sumner B. Monroe of Coudersport.

Rebecca resided in DuBois until her death on January 25, 1927. She is buried in the Morningside Cemetery in DuBois.

Wylie never mentioned his wife and children left in North Carolina. Their existence was discovered by his Pennsylvania descendants at the end of the 20th century. Apparently there were at least suspicions among Wiley's North Carolina clan that he had started life anew in the North.

References:

Apgar, Dorothy E., ed. (1988) Descendants of Johannes Peter Apgard , Vol 11, Descendants of Conrad Apgar, researched by Wayne Westly Apgar, published by the Apgar Family Association.

Combined Service Records for 22d North Carolina Infantry, (A-M), microfilm at U.S. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Demarco, Claire (1999) Personal records.

Hawkins, John O. (1994) biosketch of "Wylie/Wiley Hamby", sent to and finished by Cleora L. Bolam.

Obituary of Wiley Hamby, (1901) "Formerly a Confederate Soldier, late a Union man", DuBois, Pennsylvania, May 2, 1901. Furnished by Cleora L. Bolam.

Records of Service in the Confederate Forces, microfilm in U.S. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

written by Michael A. Apgar, November 12, 2000

by Michael A. Apgar, November 12, 2000

Wylie Hamby (nee "Wiley") was born between 1830 and 1836 in either Caldwell County, Yadkin County, or Asheville, North Carolina. (based on three conflicting references.) He was the oldest son of Martin Hamby and his wife Elizabeth Wells who married August 9, 1832. Wiley's father died when he was still an adolescent, leaving his mother with five young children. Wiley probably never knew when he was born. His mother was reportedly either blind, deaf or senile, helping to account for confusion about when Wiley was born. It also suggests that she would have been incapable of raising children on her own. This may explain the following line found in the Caldwell County (NC) records: "1850 January Term: Sheriff to bring orphan children of Martin Hamby deceased: Wiley, William and James".

Wiley's name appears on the 1852 tax list for Caldwell County, NC: "Hamby, Wiley, no land, 1 white poll". This indicates that he should have been 21 years old (which would make his birth in 1830).

Wiley married Martha Jane Mays (or Mayes) in Caldwell County on May 22, 1856. Martha Jane was born in 1840 or 1841. She was the oldest child of Morgan M. and Nancy (Day) Mays. The 1860 Caldwell County Census (taken July 28, 1860) includes, under "Buffalo District": "W.A. Hamby, 24, farmer, no real estate, personal estate $20, born in North Carolina, can't read and write, and in his household is Jane Hamby, 19, female, white, and Lucinda Hamby, 1, female, white." Wiley and Martha Jane also had a son, James, born about 1861.

The ‘War for Southern Independence' was nearly a year old, when Wiley enlisted as a private in Company A of the 22nd North Carolina Infantry, Volunteers for a term of three years. He was then 26 years old. His mustering in took place on March 19, 1862, at Lenoia, North Carolina.

The regiment had been organized immediately after hostilities began in April 1861. It was already in the field in Virginia. Wiley traveled there and took his place in the ranks as a new recruit.

James M. Hamby, who may have been Wiley's brother, had enlisted in the same unit when it was originally formed. James was 21 years old at the time. He also came from Caldwell County, North Carolina.

Apparently James got sick shortly after his army debut. Company returns identify him as a "nurse in hospital" in September 1861. (Typically nurses were soldiers who had entered the hospital as patients and were sufficiently recovered to help, but not so when they were fit for return to their units.)

Wiley must have fallen victim to disease too. His name appears on the role of Chimborazo Hospital No. 5 in Richmond on May 12, 1862 with the notation "diarrhea". He made a relatively rapid recovery, because on May 18th he was "sent to Camp Winder".

A pay statement in James' file indicates that he was paid $11/month for the three month period of June, July and August 1862. This was the standard pay for a private in the Confederate Army.

James Hamby was still in the hospital "Chirborazo Richmond No. 4" on October 28h 1862. The record indicates that he stayed there until February 6h 1863. By that time, the 22nd North Carolina was a veteran regiment in General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia.

The 22nd North Carolina suffered heavy casualties on the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg, July 1, 1863, in the fighting for MacPherson's Ridge, northwest of the town. On the third day of the battle, the regiment was part of General Pettigrew's command, which participated in the major frontal assault on the Union line on Cemetery Ridge which is known as "Pickett's Charge". The 22nd North Carolina was in the division temporarily commanded by James Lane, in the brigade commanded by Colonel Loughran. It assaulted the position just west of Cemetery Hill, which was held by the 10th Connecticut, the 1st Delaware and the 11th New Jersey. Confederate soldiers pressed forward into a hailstorm of Union artillery and concentrated rifle fire. Losses were extremely heavy, including 30 stands of colors (regimental flags). Many of the flags were lost, because they were carried in advance of the troops and casualties were so heavy that no one was able to bring them off the field.

There are no surviving muster cards to indicate whether Wiley and James were present with their regiment during most of 1863. However, a muster card for July & August 1864 notes that James was "captured July 3d 1863 at Gettysburg". James' name does not appear with those of Confederate prisoners taken to Fort Delaware, so the wound he received may have been mortal. A Roll of Honor card in Wiley's file (possibly for 1863, based on the sequence in which this record appears on the microfilm) indicates that he was "slightly wounded". However, the date, place and nature of the wound are not specified.

Wiley Hamby, a future member of the Apgar Family, may have been a participant in "Pickett's Charge", perhaps the most famous clash of the, Civil War. Ironically, although at least 150 Apgar family members served in the ranks of the Union Army, none of them were present at this point of this most famous struggle. Thus, the sole Apgar family participant in this storied event may have been a Confederate!

It is uncertain when Wiley was promoted to Corporal. Certainly the losses in the regiment created opportunities for promotion. At any rate, company muster rolls for July & August and September & October 1864 indicate that "W.A. Hamby, 2nd Corpl, CoA 22nd NC Infy" was "present".

Wiley's name also appears on receipt rolls for clothing on March 20th, April 3rd, November 5th, November 14th, and November 2nd 1864. Therefore, it seems that, except for his hospitalization for disease immediately after enlisting and some period of recuperation after he was wounded, Wiley must have served continuously with the 22nd North Carolina Infantry from the time of his enlistment until almost the end of the war.

A register of prisoners, dated March 7, 1865 for the Union Army of the Potomac includes "W.A. Hamby, CpL 22 NC-Co H" as a "Rebel Deserter". In the space for "Arms received", there is a notation "M. E.", which may stand for "musket, Enfield".

At the time Wily finally decided to throw in the towel the Confederacy was clearly on its last legs. General Grant had bottled up the remnants of the Army of Northern Virginia at Richmond and Petersburg. The Confederates were in the last days of a siege, which they could not break. General Sherman, whose destructive March to the Sea had split the Confederacy, was moving northward through the Carolinas. In a matter of weeks, the Confederate Capital would fall and the Confederate -cause would be lost. Thus, impending defeat, rather than disillusionment with "The Cause" would seem to have been Wiley's motivation for surrender.

Wylie's name also appears on another form, "Register of Rebel deserters, Provost Marshall General Wash, DC". This one includes "Sent from Army of Potomac, Taken oath trans. furnished to Oil City PA". This may have been a transfer to a temporary holding place for prisoners, with the end of the war at hand and the other prisons overcrowded. Perhaps since he voluntarily left the Confederate Army and took an oath of allegiance to the United States, Wylie was at liberty. At any rate, it helps to explain Wylie's presence in west-central Pennsylvania before the war officially ended.

When Wiley left the Confederate army, he also changed his name to Wylie (never using Wiley again) and deserted his family in North Carolina. His first wife, Martha, raised their son, James, who later married and had a family of his own. Wiley and Martha's daughter, Lucinda, did not survive to adulthood. In a letter dated January 7, 1892, Wylie's mother-in-law wrote: "My oldest child's name is Martha Jane ... Martha married Wiley Hamby and had two children. He went to the war in '61 and a few days before the war stopped he went over to the federal army and has never come back. " In 1920, Martha was still alive at the age of 82, and living with her widowed sister, Sarah.

Wylie settled in Williamsport, PA. According to his obituary (which is loaded with fanciful material, including claims that he had been a member of a prominent slave-owning family and had been a Confederate officer), Wylie first took a job at a local lumber mill. Shortly after the war he embarked in farming and lumbering in Lycoming County. There, Wylie married Rebecca C. Apgar (10.1.2.9.), the daughter of John S. and Jane (Clendenin) Apgar. Rebecca had been born in Lycoming County on December 27, 1845. Two of Rebecca's brothers were veteran's of the Union Army.

In 1888 Wylie and Rebecca, with their 4 sons and a daughter, moved to DuBois, Pennsylvania. There, Wylie worked as a shoemaker until the time he died in May 1901. He was a prominent and active member of the Presbyterian Church, and was reportedly "well known and highly respected, and his death is generally regretted". Wylie was buried in Trout Run, near Williamsport, his former home.

Wylie and Rebecca's children attended Wylie's funeral. They included: Harry W. Hamby, a passenger brakeman on the Allegheny Valley Railroad; John L. Hamby, a yard conductor for the Buffalo, Rochester and Pittsburgh Railroad; Philip A. Hamby, editor of the Davis (W.Va.) News; Ray R. Hamby, foreman and part owner of the Johnsonbury Breeze, and Mrs Sumner B. Monroe of Coudersport.

Rebecca resided in DuBois until her death on January 25, 1927. She is buried in the Morningside Cemetery in DuBois.

Wylie never mentioned his wife and children left in North Carolina. Their existence was discovered by his Pennsylvania descendants at the end of the 20th century. Apparently there were at least suspicions among Wiley's North Carolina clan that he had started life anew in the North.

References:

Apgar, Dorothy E., ed. (1988) Descendants of Johannes Peter Apgard , Vol 11, Descendants of Conrad Apgar, researched by Wayne Westly Apgar, published by the Apgar Family Association.

Combined Service Records for 22d North Carolina Infantry, (A-M), microfilm at U.S. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Demarco, Claire (1999) Personal records.

Hawkins, John O. (1994) biosketch of "Wylie/Wiley Hamby", sent to and finished by Cleora L. Bolam.

Obituary of Wiley Hamby, (1901) "Formerly a Confederate Soldier, late a Union man", DuBois, Pennsylvania, May 2, 1901. Furnished by Cleora L. Bolam.

Records of Service in the Confederate Forces, microfilm in U.S. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

written by Michael A. Apgar, November 12, 2000

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement