Georgia Governor Gilmer made the following observations of Austin Dabney:

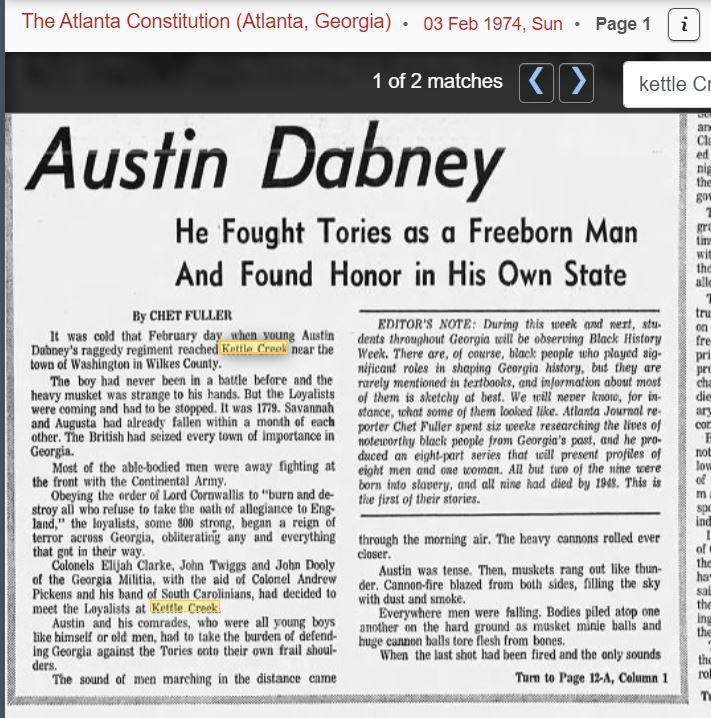

"In the beginning of the Revolutionary conflict, a man by the name of Aycock removed to Wilkes County, having in his possession a mulatto boy, who passed for and was treated as his slave. The boy had been called Austin, to which the Captain to whose company he was attached added Dabney.

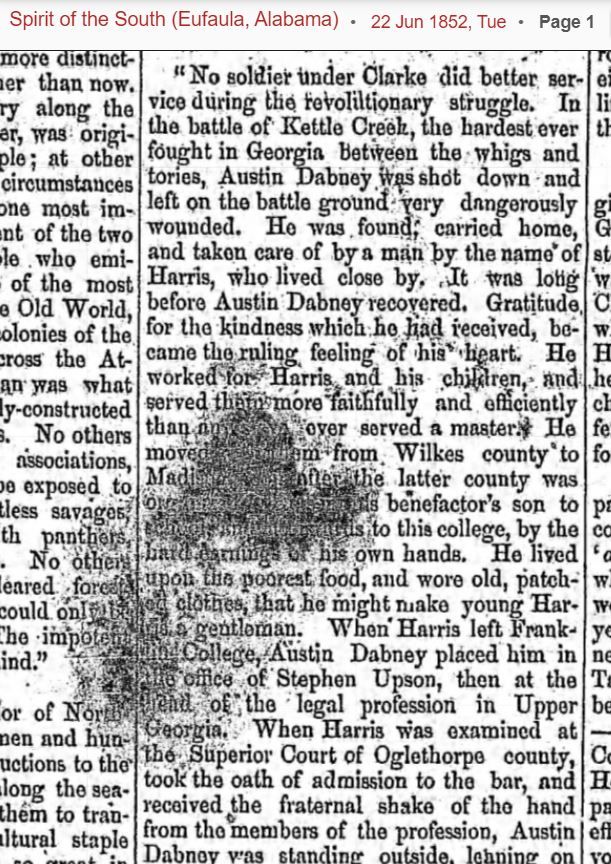

Dabney proved himself a good soldier. In many a skirmish with the British and Tories, he acted a conspicuous part. He was with Colonel Elijah Clarke in the battle at Kettle Creek, and was severely wounded by a rifle-ball passing through his thigh, by which he was made a cripple for life. He was unable to do further military duty, and was without means to procure due attention to his wound, which threatened his life. In this suffering condition he was taken into the house of a Mr. Harris, where he was kindly cared for until he recovered. He afterwards laboured for Harris and his family more faithfully than any slave could have been made to do.

After the close of the war, when prosperous times came, Austin Dabney acquired property. In the year 18__, he removed to Madison County, carrying with him his benefactor and family. Here he became noted for his great fondness for horses and the turf. He attended all the races in the neighbouring counties, and betted to he extent of his means. His courteous behaviour and good temper always secured him gentlemen backers. His means were aided by a pension which he received from the United States.

In the distribution of the public lands by lottery among the people of Georgia, the Legislature gave to Dabney a lot of land in the county of Walton. The Hon. Mr. Upson, then a representative from Oglethorpe, was the member who moved the passage of the law, giving him the lot of land.

At the election for members of the Legislature the year after, the County of Madison was distracted by the animosity and strife of an Austin Dabney and an Anti-Austin Dabney party. Many of the people were highly incensed that a mulatto negro should receive a gift of the land which belonged to the freemen of Georgia. Dabney soon after removed to the land given him by the state and carried with him the family of Harris, and continued to labour for them, and appropriated whatever he made for their support, except what was necessary for his coarse clothing and food. Upon his death, he left them all his property. The eldest son of his benefactor he sent to Franklin College, and afterwards supported him whilst he studied law with Mr. Upson, in Lexington. When Harris was undergoing his examination, Austin was standing outside of the bar, exhibiting great anxiety in his countenance; and when his young protégé was sworn in, he burst into a flood of tears. He understood his situation very well, and never was guilty of impertinence. He was one of the best chroniclers of the events of the Revolutionary War in Georgia. Judge Dooly thought much of him, for he had served under his father, Colonel Dooly. It was Dabney's custom to be at the public house at Madison, where the judge stopped during court, and he took much pains in seeing his horse well attended to. He frequently came into the room where the judges and lawyers were assembled on the evening before the court, and seated himself upon a stool or some low place, where he would commence a parley with any one who chose to talk with him.

He drew his pension in Savannah, where he went once a year for this purpose. On one occasion he went to Savannah in company with his neighbour, Colonel Wyley Pope. They travelled together on the most familiar terms, until they arrived in the streets of the town. Then the Colonel observed to Austin that he was a man of sense, and knew that it was not suitable for him to be seen riding side by side with a coloured man through the streets of Savannah; to which Austin replied that the understood that matter very well. Accordingly, when they came to the principal street, Austin checked his horse and fell behind. They had not gone very far before Colonel Pope passed by the house of General James Jackson, who was the Governor of the State. Upon looking back, he saw the Governor run out of the house, seize Austin's hand, shake it as it he had been his long absent brother, draw him off his horse, and carry him into his house, where they stayed whilst in town. Colonel Pope used to tell this anecdote with much glee, adding that he felt chagrined when he ascertained that whilst he passed his time at a tavern, unknown and uncared for, Austin was the honoured guest of the Governor."

Georgia Governor Gilmer made the following observations of Austin Dabney:

"In the beginning of the Revolutionary conflict, a man by the name of Aycock removed to Wilkes County, having in his possession a mulatto boy, who passed for and was treated as his slave. The boy had been called Austin, to which the Captain to whose company he was attached added Dabney.

Dabney proved himself a good soldier. In many a skirmish with the British and Tories, he acted a conspicuous part. He was with Colonel Elijah Clarke in the battle at Kettle Creek, and was severely wounded by a rifle-ball passing through his thigh, by which he was made a cripple for life. He was unable to do further military duty, and was without means to procure due attention to his wound, which threatened his life. In this suffering condition he was taken into the house of a Mr. Harris, where he was kindly cared for until he recovered. He afterwards laboured for Harris and his family more faithfully than any slave could have been made to do.

After the close of the war, when prosperous times came, Austin Dabney acquired property. In the year 18__, he removed to Madison County, carrying with him his benefactor and family. Here he became noted for his great fondness for horses and the turf. He attended all the races in the neighbouring counties, and betted to he extent of his means. His courteous behaviour and good temper always secured him gentlemen backers. His means were aided by a pension which he received from the United States.

In the distribution of the public lands by lottery among the people of Georgia, the Legislature gave to Dabney a lot of land in the county of Walton. The Hon. Mr. Upson, then a representative from Oglethorpe, was the member who moved the passage of the law, giving him the lot of land.

At the election for members of the Legislature the year after, the County of Madison was distracted by the animosity and strife of an Austin Dabney and an Anti-Austin Dabney party. Many of the people were highly incensed that a mulatto negro should receive a gift of the land which belonged to the freemen of Georgia. Dabney soon after removed to the land given him by the state and carried with him the family of Harris, and continued to labour for them, and appropriated whatever he made for their support, except what was necessary for his coarse clothing and food. Upon his death, he left them all his property. The eldest son of his benefactor he sent to Franklin College, and afterwards supported him whilst he studied law with Mr. Upson, in Lexington. When Harris was undergoing his examination, Austin was standing outside of the bar, exhibiting great anxiety in his countenance; and when his young protégé was sworn in, he burst into a flood of tears. He understood his situation very well, and never was guilty of impertinence. He was one of the best chroniclers of the events of the Revolutionary War in Georgia. Judge Dooly thought much of him, for he had served under his father, Colonel Dooly. It was Dabney's custom to be at the public house at Madison, where the judge stopped during court, and he took much pains in seeing his horse well attended to. He frequently came into the room where the judges and lawyers were assembled on the evening before the court, and seated himself upon a stool or some low place, where he would commence a parley with any one who chose to talk with him.

He drew his pension in Savannah, where he went once a year for this purpose. On one occasion he went to Savannah in company with his neighbour, Colonel Wyley Pope. They travelled together on the most familiar terms, until they arrived in the streets of the town. Then the Colonel observed to Austin that he was a man of sense, and knew that it was not suitable for him to be seen riding side by side with a coloured man through the streets of Savannah; to which Austin replied that the understood that matter very well. Accordingly, when they came to the principal street, Austin checked his horse and fell behind. They had not gone very far before Colonel Pope passed by the house of General James Jackson, who was the Governor of the State. Upon looking back, he saw the Governor run out of the house, seize Austin's hand, shake it as it he had been his long absent brother, draw him off his horse, and carry him into his house, where they stayed whilst in town. Colonel Pope used to tell this anecdote with much glee, adding that he felt chagrined when he ascertained that whilst he passed his time at a tavern, unknown and uncared for, Austin was the honoured guest of the Governor."

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement