Confederate staff officer, wounded in "Pickett's Charge" - Prisoner of War- Spy - Pardoned by Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson.

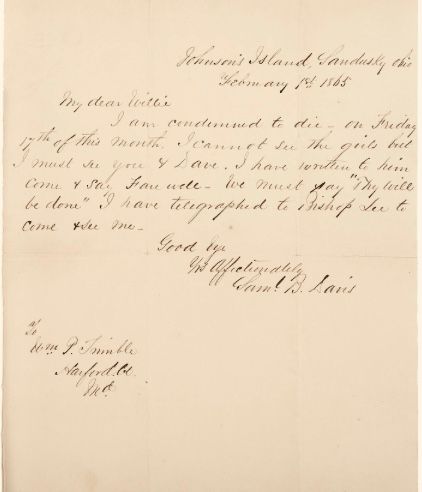

Davis pondered his impending execution writing he was prepared to "die like a man and like a soldier."

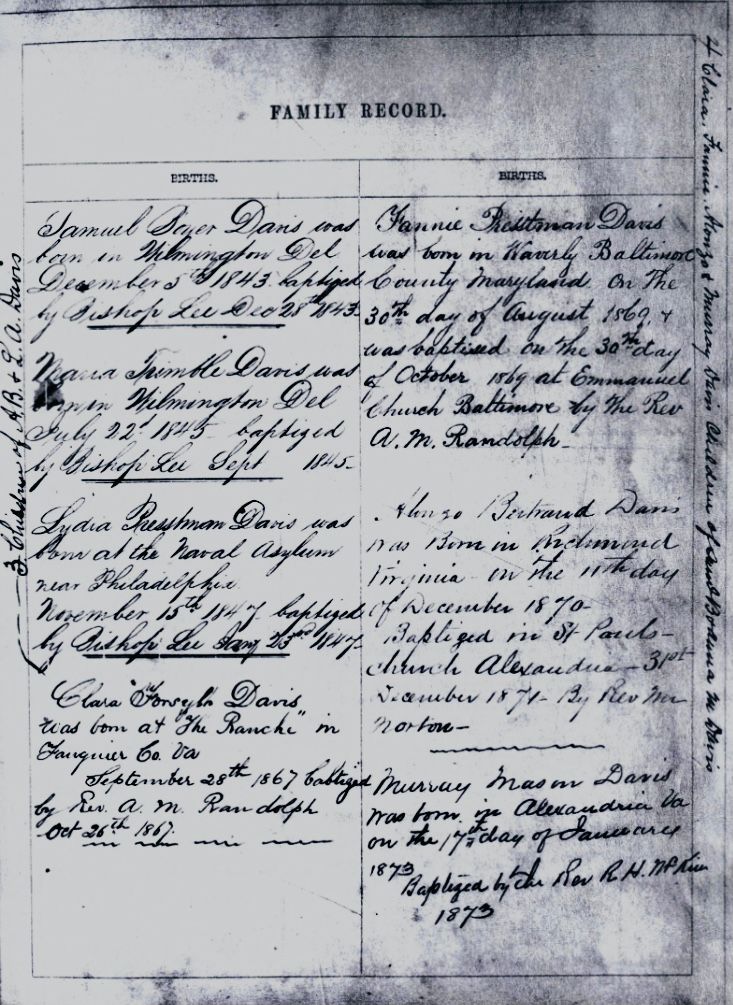

Note: Captain Samuel Boyer Davis of Delaware, was a younger first cousin of Major Samuel Boyer Davis of Louisiana and Texas and Florian Davis of Louisiana. He also is the nephew of Confederate Lieutenant Colonel Stephen Wilson Presstman of New Castle, Delaware, grandson of Colonel Samuel Boyer Davis of Delaware and great nephew by marriage of Confederate General Isaac Ridgeway Trimble.

Alexandria Gazette 25 Sept. 1914 obituary

Wilmington (Del.) Morning News 13 Mar. 1950

Wilmington (Del.) Morning News 13 Aug. 1960

"Delaware's Samuel Boyer Davis: A Near Death Experience by Thomas J. Ryan (2013)

Author: Captain Samuel Boyer Davis

Original publication date 1892

Author John Bakeless. Published by the Lippincott Co., 1970, Philadelphia, Penna.

United States National Park Service records,

Staff Officers, Non-Regimental Enlisted Men,

First Lieutenant/Aide-de-Camp,

Captain/Assistant Adjutant General

Confederate staff officer, wounded in "Pickett's Charge" - Prisoner of War- Spy - Pardoned by Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson.

Davis pondered his impending execution writing he was prepared to "die like a man and like a soldier."

Note: Captain Samuel Boyer Davis of Delaware, was a younger first cousin of Major Samuel Boyer Davis of Louisiana and Texas and Florian Davis of Louisiana. He also is the nephew of Confederate Lieutenant Colonel Stephen Wilson Presstman of New Castle, Delaware, grandson of Colonel Samuel Boyer Davis of Delaware and great nephew by marriage of Confederate General Isaac Ridgeway Trimble.

Alexandria Gazette 25 Sept. 1914 obituary

Wilmington (Del.) Morning News 13 Mar. 1950

Wilmington (Del.) Morning News 13 Aug. 1960

"Delaware's Samuel Boyer Davis: A Near Death Experience by Thomas J. Ryan (2013)

Author: Captain Samuel Boyer Davis

Original publication date 1892

Author John Bakeless. Published by the Lippincott Co., 1970, Philadelphia, Penna.

United States National Park Service records,

Staff Officers, Non-Regimental Enlisted Men,

First Lieutenant/Aide-de-Camp,

Captain/Assistant Adjutant General

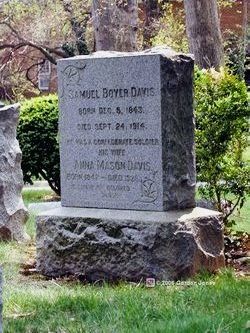

Inscription

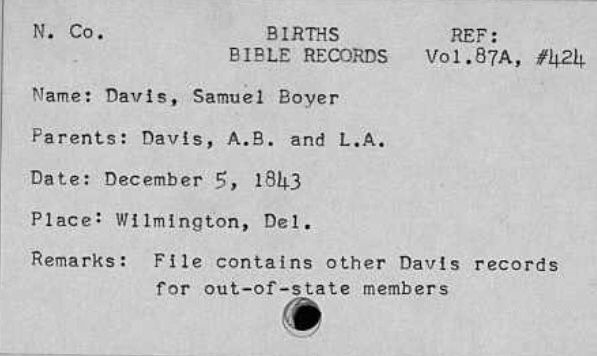

SAMUEL BOYER DAVIS

BORN DEC. 5, 1843

DIED SEPT. 14, 1914

HE WAS A CONFEDERATE SOLDIER

HIS WIFE

ANNA MASON DAVIS

BORN 1912 - DIED 1928

HE GIVETH HIS BELOVED

SLEEP

Gravesite Details

Burial Date: 09/26/1914

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement