The one who REMEMBERED IT ALL As a centenarian, a small-town Vermont woman became the narrator of a sweeping African-American family tale BY JAMES SULLIVAN

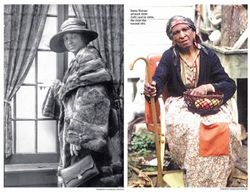

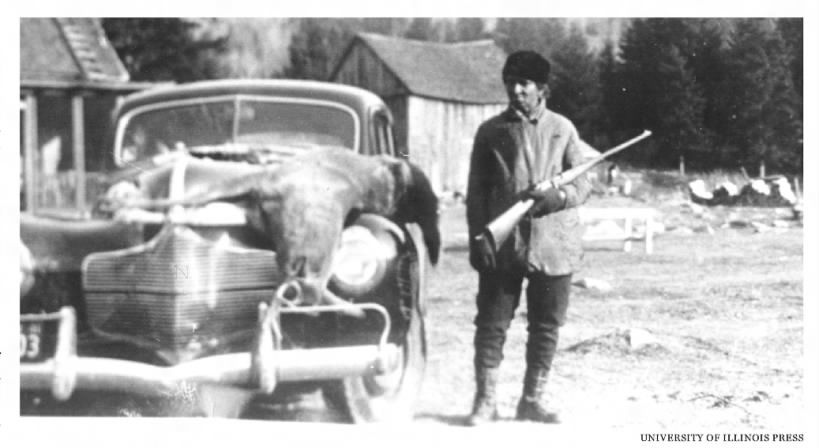

Vermont has always been one of the whitest states in the nation, with more than 95 percent of its population counted as white in the 2010 Census. The little town of Grafton in southeast Vermont is even whiter than the state as a whole: Of its 700 or so residents, fewer than 1 percent are people of color. But Grafton is the home of a truly compelling African-American legacy: It was the home of Daisy Turner, who lived to be 104 years old and, late in life, became the subject of a significant oral history project. Born in Grafton in 1883, Turner recounted tales that documented her grandfather's arrival as a slave in America, her father's escape from bondage, and his eventual settlement on the Grafton homestead the family called Journey's End. Daisy Turner's story, recorded over several years by Vermont historian Jane C.

Beck, won a Peabody Award in 1990. It inspired a children's book and was made into a documentary film. Not long before her death in 1988, Turner was filmed for an appearance for Ken Burns's historic Civil War series, which is scheduled for rebroadcast on PBS in a restored version in September. Now Beck has published (last month) the de finitive account of the Turner family of Grafton, "Daisy Turner's Kin: An African American Family Saga." It is the culmination of Daisy's dearest wish: that her family's legacy be remembered for posterity. "She felt her story wouldn't be taken seriously unless it was printed," says Beck.

"And she was right, in many ways. Once a person is dead, their voice is gone." The printed word held powerful meaning for Daisy and her family. Throughout his life, her father, Alec Turner, remained especially proud of his ability to read and write. Born into slavery in Virginia, where it was against the law to help slaves become literate, Turner learned to read with the help of a young woman named Zephie, a granddaughter of the plantation owner. Zephie encouraged Alec to leave the plantation and make his way to Vermont, where she'd heard he could live as a free man.

After serving with the Union Army in the 1st New Jersey Cavalry and working after the Civil War in a slate quarry in Maine, Turner did settle in Vermont, in Grafton, where the town fathers were abolitionists. Daisy was born to Alec and his wife, Sally, after the death in infancy of the couple's eighth child, a boy who had been nicknamed "Enough." Beck was working as a folklorist for Vermont's State Arts Council when she encountered Daisy Turner in the early 1980s through a newspaper clipping about a 100-year-old daughter of former slaves. "It was my job to bring the traditional arts to the general public," she says. "I thought an African-American born in Vermont would have something to say to the schoolchildren in the state." From their first phone call, Turner's straightforward attitude was apparent. "Are you a prejudiced woman?" she asked Beck point-blank. Beck writes that she was caught off guard: "I stammered that I didn't think so.

Her voice became warm and welcoming: 'Well, come She was not disappointed. "Daisy was a marvelous storyteller," she recalls. "I was drawn right in. I could not believe what I was hearing." Among many other details, Turner told Beck that her grandfather had been involved in the slave trade in Africa before being enslaved himself. She related how her father led his Civil War regiment to the plantation where he'd been a slave, and shot and killed his former overseer.

And Turner, who never married, described the facts of her own long, fiercely independent life in Vermont. "Whenever I rode by my house with my dad, he would always talk about Daisy," says David Rogers, 40, a Grafton resident who learned as an adult that he is a great-great-grandson of Alec Turner. He recalls that Daisy "used to have pots and pans on the door so if you opened it she could tell you were coming in." Some time ago Rogers submitted to a DNA test, which confirmed the relationship. "I guess he was from Nigeria, if I remember right," he says, referring to Daisy's grandfather. Rogers's daughters have since learned more about the Turner family in school.

"We have a lot of heritage here," he says. Daisy didn't live to be 100 on her own without having some headstrong beliefs and opinions, Beck says. No one crossed her without paying a price: In the 1920s, when a man broke off his.engagement to Daisy, she sued him for breech of promise and won. "I expected to fall out of favor with her," says Beck. "She was suspicious of people. But we built a good relationship." Cynthia Gibbs, who works part time as the assistant town clerk in Grafton, remembers eating meals at a "home restaurant" run by Aunt Zeb, as her family called one of Daisy's sisters. "She was a terrific cook," says Gibbs.

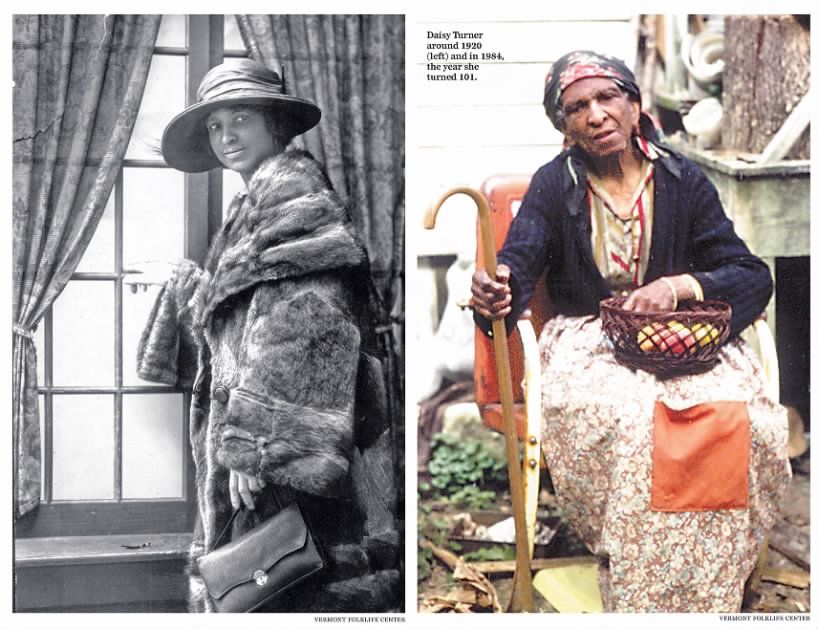

Daisy, on the other hand, was known around town as a firecracker. "She was a character, I guess," Gibbs says with a laugh. "Daisy, she scared everybody. She'd walk around town with her shotgun. She liked the fact that she was of a different color.

She thrived on it." In the course of Beck's interviews, Turner would sometimes grow angry while recounting land disputes, or her efforts to secure her father's pension. "She would get herself into a real tizzy," Beck recalls. "Finally I learned to say, 'OK, Aunt Daisy, tell me what you did at Christmas. Have some ginger Then she would calm down I could shift her." Beck suspects that those moments of frustration weren't a product of Daisy's advanced age, but that she'd been that way her whole life. Turner's stories capture some of that spirit.

But then the purpose of oral history, in Beck's view, is to tell the stories as the subject recalls them. "While memory can be unreliable," she writes in "Daisy Turner's Kin," "it is always meaningful." Daisy could sometimes fall prey to embellishment, she says, but by all accounts her father, Alec, the family patriarch, was exacting in handing down the family chronicles. Given the recently heightened discussions of racism in America after a series of high-profile incidents of police brutality and the church massacre last month in Charleston, S.C., Beck would be eager to see Daisy's story find a renewed audience. "I hope it will help the conversation and people will be drawn to it, both African-American and white or blue, or yellow, or whatever," she says. "I think stories can do that.".

The one who REMEMBERED IT ALL As a centenarian, a small-town Vermont woman became the narrator of a sweeping African-American family tale BY JAMES SULLIVAN

Vermont has always been one of the whitest states in the nation, with more than 95 percent of its population counted as white in the 2010 Census. The little town of Grafton in southeast Vermont is even whiter than the state as a whole: Of its 700 or so residents, fewer than 1 percent are people of color. But Grafton is the home of a truly compelling African-American legacy: It was the home of Daisy Turner, who lived to be 104 years old and, late in life, became the subject of a significant oral history project. Born in Grafton in 1883, Turner recounted tales that documented her grandfather's arrival as a slave in America, her father's escape from bondage, and his eventual settlement on the Grafton homestead the family called Journey's End. Daisy Turner's story, recorded over several years by Vermont historian Jane C.

Beck, won a Peabody Award in 1990. It inspired a children's book and was made into a documentary film. Not long before her death in 1988, Turner was filmed for an appearance for Ken Burns's historic Civil War series, which is scheduled for rebroadcast on PBS in a restored version in September. Now Beck has published (last month) the de finitive account of the Turner family of Grafton, "Daisy Turner's Kin: An African American Family Saga." It is the culmination of Daisy's dearest wish: that her family's legacy be remembered for posterity. "She felt her story wouldn't be taken seriously unless it was printed," says Beck.

"And she was right, in many ways. Once a person is dead, their voice is gone." The printed word held powerful meaning for Daisy and her family. Throughout his life, her father, Alec Turner, remained especially proud of his ability to read and write. Born into slavery in Virginia, where it was against the law to help slaves become literate, Turner learned to read with the help of a young woman named Zephie, a granddaughter of the plantation owner. Zephie encouraged Alec to leave the plantation and make his way to Vermont, where she'd heard he could live as a free man.

After serving with the Union Army in the 1st New Jersey Cavalry and working after the Civil War in a slate quarry in Maine, Turner did settle in Vermont, in Grafton, where the town fathers were abolitionists. Daisy was born to Alec and his wife, Sally, after the death in infancy of the couple's eighth child, a boy who had been nicknamed "Enough." Beck was working as a folklorist for Vermont's State Arts Council when she encountered Daisy Turner in the early 1980s through a newspaper clipping about a 100-year-old daughter of former slaves. "It was my job to bring the traditional arts to the general public," she says. "I thought an African-American born in Vermont would have something to say to the schoolchildren in the state." From their first phone call, Turner's straightforward attitude was apparent. "Are you a prejudiced woman?" she asked Beck point-blank. Beck writes that she was caught off guard: "I stammered that I didn't think so.

Her voice became warm and welcoming: 'Well, come She was not disappointed. "Daisy was a marvelous storyteller," she recalls. "I was drawn right in. I could not believe what I was hearing." Among many other details, Turner told Beck that her grandfather had been involved in the slave trade in Africa before being enslaved himself. She related how her father led his Civil War regiment to the plantation where he'd been a slave, and shot and killed his former overseer.

And Turner, who never married, described the facts of her own long, fiercely independent life in Vermont. "Whenever I rode by my house with my dad, he would always talk about Daisy," says David Rogers, 40, a Grafton resident who learned as an adult that he is a great-great-grandson of Alec Turner. He recalls that Daisy "used to have pots and pans on the door so if you opened it she could tell you were coming in." Some time ago Rogers submitted to a DNA test, which confirmed the relationship. "I guess he was from Nigeria, if I remember right," he says, referring to Daisy's grandfather. Rogers's daughters have since learned more about the Turner family in school.

"We have a lot of heritage here," he says. Daisy didn't live to be 100 on her own without having some headstrong beliefs and opinions, Beck says. No one crossed her without paying a price: In the 1920s, when a man broke off his.engagement to Daisy, she sued him for breech of promise and won. "I expected to fall out of favor with her," says Beck. "She was suspicious of people. But we built a good relationship." Cynthia Gibbs, who works part time as the assistant town clerk in Grafton, remembers eating meals at a "home restaurant" run by Aunt Zeb, as her family called one of Daisy's sisters. "She was a terrific cook," says Gibbs.

Daisy, on the other hand, was known around town as a firecracker. "She was a character, I guess," Gibbs says with a laugh. "Daisy, she scared everybody. She'd walk around town with her shotgun. She liked the fact that she was of a different color.

She thrived on it." In the course of Beck's interviews, Turner would sometimes grow angry while recounting land disputes, or her efforts to secure her father's pension. "She would get herself into a real tizzy," Beck recalls. "Finally I learned to say, 'OK, Aunt Daisy, tell me what you did at Christmas. Have some ginger Then she would calm down I could shift her." Beck suspects that those moments of frustration weren't a product of Daisy's advanced age, but that she'd been that way her whole life. Turner's stories capture some of that spirit.

But then the purpose of oral history, in Beck's view, is to tell the stories as the subject recalls them. "While memory can be unreliable," she writes in "Daisy Turner's Kin," "it is always meaningful." Daisy could sometimes fall prey to embellishment, she says, but by all accounts her father, Alec, the family patriarch, was exacting in handing down the family chronicles. Given the recently heightened discussions of racism in America after a series of high-profile incidents of police brutality and the church massacre last month in Charleston, S.C., Beck would be eager to see Daisy's story find a renewed audience. "I hope it will help the conversation and people will be drawn to it, both African-American and white or blue, or yellow, or whatever," she says. "I think stories can do that.".

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement