1 NOV 2021

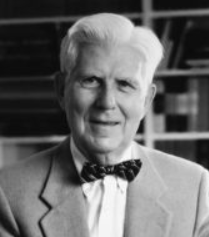

Aaron Temkin Beck (July 18, 1921 – November 1, 2021) was an American psychiatrist who was professor emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania. He is regarded as the father of cognitive therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy. His pioneering methods are widely used in the treatment of clinical depression and various anxiety disorders. Beck also developed self-report measures for depression and anxiety, notably the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), which became one of the most widely used instruments for measuring the severity of depression. In 1994, he and his daughter, the psychologist Judith S. Beck, founded the nonprofit Beck Institute for Cognitive Behavior Therapy, which provides CBT treatment and training and conducts CBT research. Beck served as President Emeritus of the organization up until his death on November 1, 2021.

Beck is noted for his writings on psychotherapy, psychopathology, suicide, and psychometrics. He has published more than 600 professional journal articles, and authored or co-authored 25 books. He was named one of the "Americans in history who shaped the face of American psychiatry", and one of the "five most influential psychotherapists of all time" by The American Psychologist in July 1989. His work at the University of Pennsylvania inspired Martin Seligman to refine his own cognitive techniques and later work on learned helplessness.

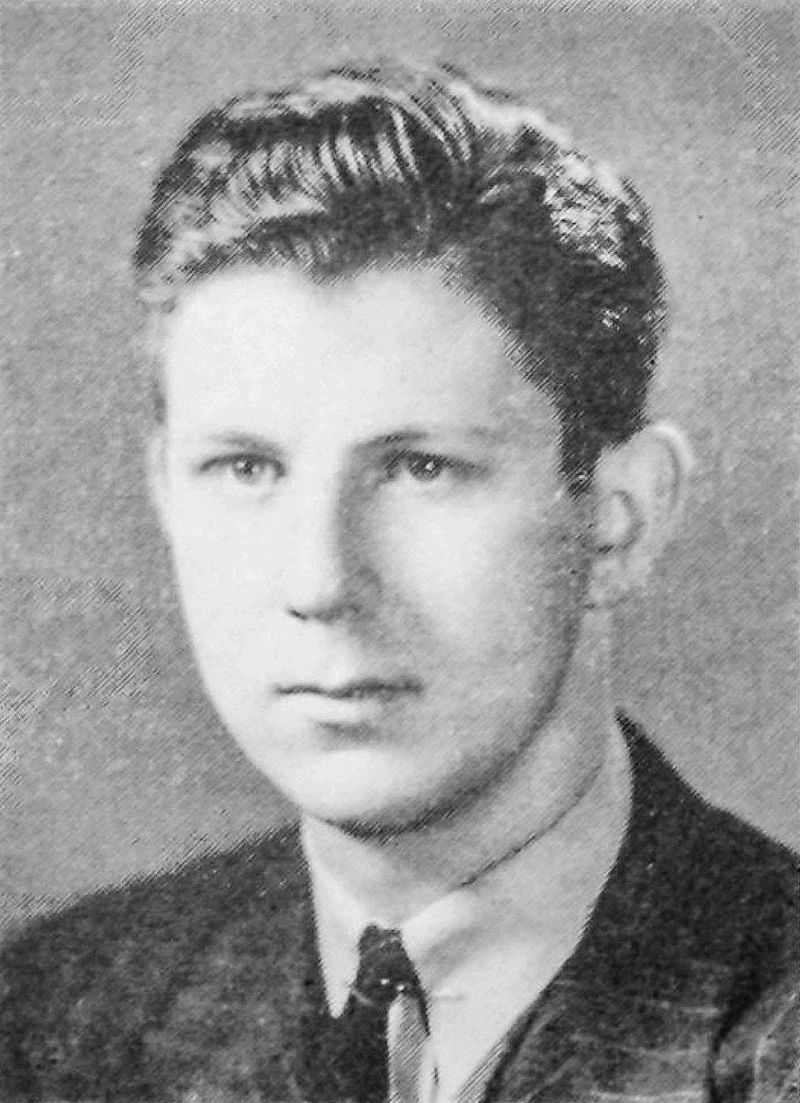

Beck was born in Providence, Rhode Island, US, the youngest of four children born to Ukrainian Jewish immigrants. Beck was married in 1950 to Phyllis W. Beck, who was the first woman judge on the appellate court of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and whose youngest daughter, Alice Beck Dubow, is also a judge on the appellate court of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Together they had four children: Roy, Judy, Dan, and Alice. Beck's daughter Judith is a prominent cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) educator and clinician, who wrote the basic text in the field. She is a co-founder of the non-profit Beck Institute. He turned 100 on July 18, 2021.

Beck attended Brown University, graduating magna cum laude in 1942. At Brown, he was elected a member of the Phi Beta Kappa Society, was an associate editor of The Brown Daily Herald, and received the Francis Wayland Scholarship, William Gaston Prize for Excellence in Oratory, and Philo Sherman Bennett Essay Award. Beck attended Yale Medical School, graduating with an MD in 1946.

He began to specialize in neurology, reportedly liking the precision of its procedures. However, due to a shortage of psychiatry residents he was instructed to do a six-month rotation in that field, and became absorbed in psychoanalysis, despite initial wariness.

After completing his medical internships and residencies from 1946 to 1950, Beck became Fellow in psychiatry at the Austen Riggs Center, a private mental hospital in the mountains of Stockbridge, Massachusetts, until 1952. At that time it was a center of ego psychology with an unusual degree of collaboration between psychiatrists and psychologists, including David Rapaport.

Beck then completed military service as assistant chief of neuropsychiatry at Valley Forge Army Hospital in the United States Military.

Beck then joined the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania (Penn) in 1954. The department chair was Kenneth Ellmaker Appel, a psychoanalyst who was president of the American Psychiatric Association, whose efforts to expand the presence and relatedness of psychiatry had a big influence on Beck's career. At the same time, Beck began formal training in psychoanalysis at the Philadelphia Institute of the American Psychoanalytic Association.

Beck requested a sabbatical and would go into private practice for five years.

In 1962, he was already making notes about patterns of thoughts in depression, emphasizing what can be observed and tested by anyone and treated in the present. He strengthened the new alliance with the psychiatrist Stunkard, and extended his links to psychologist colleagues such as Seymour Feshbach and Irving Sigel, thus keeping abreast of developments in cognitive psychology, as he did also from the new Center for Cognitive Science at Harvard University. He was particularly engaged by George Kelly's personal construct theory and Jean Piaget's schemas. Beck's first articles on the cognitive theory of depression, in 1963 and 1964 in the Archives of General Psychiatry, maintained the psychiatric context of ego psychology but then turned to concepts of realistic and scientific thinking in the terms of the new cognitive psychology, extended to become a therapeutic need.

Beck's notebooks were also filled with self-analysis, where at least twice a day for several years he wrote out his own "negative" (later "automatic") thoughts, rated with a percentile belief score, classified and restructured.

The psychologist who would become most important for Beck was Albert Ellis, whose own faith in psychoanalysis had crumbled by the 1950s. He had begun presenting his "rational therapy" by the mid 1950s. Beck recalls that Ellis contacted him in the mid 1960s after his two articles in the Archives of General Psychiatry, and therefore he discovered Ellis had developed a rich theory and pragmatic therapy that he was able to use to some extent as a framework blended with his own, though he disliked Ellis's technique of telling patients what he thought was going on rather than helping the client to learn for themselves empirically. Psychoanalyst Gerald E. Kochansky remarked in 1975 in a review of one of Beck's books that he could no longer tell if Beck was a psychoanalyst or a devotee of Ellis. Beck highlighted the classical philosophical Socratic method as an inspiration, while Ellis highlighted disputation which he stated was not anti-empirical and taught people how to dispute internally. Both Beck and Ellis cited aspects of the ancient philosophical system of stoicism as a forerunner of their ideas, though Ellis wrote more about this; both mistakenly cited Cicero as a stoic.

In 1967, becoming active again at University of Pennsylvania, Beck still described himself and his new therapy (as he always would quietly) as neo-Freudian in the ego psychology school, albeit focused on interactions with the environment rather than internal drives. He offered cognitive therapy work as a relatively "neutral" space and a bridge to psychology. With a monograph on depression that Beck published in 1967, according to historian Rachael Rosner: "Cognitive Therapy entered the marketplace as a corrective experimentalist psychological framework both for himself and his patients and for his fellow psychiatrists."

Working with depressed patients, Beck found that they experienced streams of negative thoughts that seemed to arise spontaneously. He termed these cognitions "automatic thoughts", and discovered that their content fell into three categories: negative ideas about oneself, the world, and the future. He stated that such cognitions were interrelated as the cognitive triad. Limited time spent reflecting on automatic thoughts would lead patients to treat them as valid.

Beck began helping patients identify and evaluate these thoughts and found that by doing so, patients were able to think more realistically, which led them to feel better emotionally and behave more functionally. He developed key ideas in CBT, explaining that different disorders were associated with different types of distorted thinking. Distorted thinking has a negative effect on a person's behaviour no matter what type of disorder they had, he found. Beck explained that successful interventions will educate a person to understand and become aware of their distorted thinking, and how to challenge its effects. He discovered that frequent negative automatic thoughts reveal a person's core beliefs. He explained that core beliefs are formed over lifelong experiences; we "feel" these beliefs to be true.

Since that time, Beck and his colleagues worldwide have researched the efficacy of this form of psychotherapy in treating a wide variety of disorders including depression, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, drug abuse, anxiety disorders, personality disorders, and many other medical conditions with psychological components. Cognitive therapy has also been applied with success to individuals with anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, and many other medical and psychiatric disorders. Some of Beck's most recent work has focused on cognitive therapy for schizophrenia, borderline personality disorder, and for patients who have had recurrent suicide attempts.

Beck's recent research on the treatment of schizophrenia has suggested that patients once believed to be non-responsive to treatment are amenable to positive change. Even the most severe presentations of the illness, such as those involving long periods of hospitalization, bizarre behavior, poor personal hygiene, self-injury, and aggressiveness, can respond positively to a modified version of cognitive behavioural treatment. Called recovery-oriented cognitive therapy (CT-R), the approach focused less on the amelioration of symptoms, but instead, on empowering the individual to identify and attain meaningful goals and a desired life.

However, some mental health professionals have opposed Beck's cognitive models and resulting therapies as too mechanistic or too limited in which parts of mental activity they will consider. From within the CBT community itself, one line of research using component analyses (dismantling studies) has found that the addition of cognitive strategies often fails to show superior efficacy over behavioral strategies alone, and that attempts to challenge thoughts can sometimes have a rebound effect. Moreover, although Beck's work was presented as a far more scientific and experimentally-based development than psychoanalysis (while being less reductive than behaviourism), Beck's key principles were not necessarily based on the general findings and models of cognitive psychology or neuroscience developing at that time but were derived from personal clinical observations and interpretations in his therapy office. And although there have been many cognitive models developed for different mental disorders and hundreds of outcome studies on the effectiveness of CBT—relatively easy because of the narrow, time-limited and manual-based nature of the treatment—there has been much less focus on experimentally proving the supposedly active mechanisms; in some cases the predicted causal relationships have not been found, such as between dysfunctional attitudes and outcomes.

In 2017, Medscape named Beck the fourth most influential physician in the past century.

1 NOV 2021

Aaron Temkin Beck (July 18, 1921 – November 1, 2021) was an American psychiatrist who was professor emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania. He is regarded as the father of cognitive therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy. His pioneering methods are widely used in the treatment of clinical depression and various anxiety disorders. Beck also developed self-report measures for depression and anxiety, notably the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), which became one of the most widely used instruments for measuring the severity of depression. In 1994, he and his daughter, the psychologist Judith S. Beck, founded the nonprofit Beck Institute for Cognitive Behavior Therapy, which provides CBT treatment and training and conducts CBT research. Beck served as President Emeritus of the organization up until his death on November 1, 2021.

Beck is noted for his writings on psychotherapy, psychopathology, suicide, and psychometrics. He has published more than 600 professional journal articles, and authored or co-authored 25 books. He was named one of the "Americans in history who shaped the face of American psychiatry", and one of the "five most influential psychotherapists of all time" by The American Psychologist in July 1989. His work at the University of Pennsylvania inspired Martin Seligman to refine his own cognitive techniques and later work on learned helplessness.

Beck was born in Providence, Rhode Island, US, the youngest of four children born to Ukrainian Jewish immigrants. Beck was married in 1950 to Phyllis W. Beck, who was the first woman judge on the appellate court of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and whose youngest daughter, Alice Beck Dubow, is also a judge on the appellate court of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Together they had four children: Roy, Judy, Dan, and Alice. Beck's daughter Judith is a prominent cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) educator and clinician, who wrote the basic text in the field. She is a co-founder of the non-profit Beck Institute. He turned 100 on July 18, 2021.

Beck attended Brown University, graduating magna cum laude in 1942. At Brown, he was elected a member of the Phi Beta Kappa Society, was an associate editor of The Brown Daily Herald, and received the Francis Wayland Scholarship, William Gaston Prize for Excellence in Oratory, and Philo Sherman Bennett Essay Award. Beck attended Yale Medical School, graduating with an MD in 1946.

He began to specialize in neurology, reportedly liking the precision of its procedures. However, due to a shortage of psychiatry residents he was instructed to do a six-month rotation in that field, and became absorbed in psychoanalysis, despite initial wariness.

After completing his medical internships and residencies from 1946 to 1950, Beck became Fellow in psychiatry at the Austen Riggs Center, a private mental hospital in the mountains of Stockbridge, Massachusetts, until 1952. At that time it was a center of ego psychology with an unusual degree of collaboration between psychiatrists and psychologists, including David Rapaport.

Beck then completed military service as assistant chief of neuropsychiatry at Valley Forge Army Hospital in the United States Military.

Beck then joined the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania (Penn) in 1954. The department chair was Kenneth Ellmaker Appel, a psychoanalyst who was president of the American Psychiatric Association, whose efforts to expand the presence and relatedness of psychiatry had a big influence on Beck's career. At the same time, Beck began formal training in psychoanalysis at the Philadelphia Institute of the American Psychoanalytic Association.

Beck requested a sabbatical and would go into private practice for five years.

In 1962, he was already making notes about patterns of thoughts in depression, emphasizing what can be observed and tested by anyone and treated in the present. He strengthened the new alliance with the psychiatrist Stunkard, and extended his links to psychologist colleagues such as Seymour Feshbach and Irving Sigel, thus keeping abreast of developments in cognitive psychology, as he did also from the new Center for Cognitive Science at Harvard University. He was particularly engaged by George Kelly's personal construct theory and Jean Piaget's schemas. Beck's first articles on the cognitive theory of depression, in 1963 and 1964 in the Archives of General Psychiatry, maintained the psychiatric context of ego psychology but then turned to concepts of realistic and scientific thinking in the terms of the new cognitive psychology, extended to become a therapeutic need.

Beck's notebooks were also filled with self-analysis, where at least twice a day for several years he wrote out his own "negative" (later "automatic") thoughts, rated with a percentile belief score, classified and restructured.

The psychologist who would become most important for Beck was Albert Ellis, whose own faith in psychoanalysis had crumbled by the 1950s. He had begun presenting his "rational therapy" by the mid 1950s. Beck recalls that Ellis contacted him in the mid 1960s after his two articles in the Archives of General Psychiatry, and therefore he discovered Ellis had developed a rich theory and pragmatic therapy that he was able to use to some extent as a framework blended with his own, though he disliked Ellis's technique of telling patients what he thought was going on rather than helping the client to learn for themselves empirically. Psychoanalyst Gerald E. Kochansky remarked in 1975 in a review of one of Beck's books that he could no longer tell if Beck was a psychoanalyst or a devotee of Ellis. Beck highlighted the classical philosophical Socratic method as an inspiration, while Ellis highlighted disputation which he stated was not anti-empirical and taught people how to dispute internally. Both Beck and Ellis cited aspects of the ancient philosophical system of stoicism as a forerunner of their ideas, though Ellis wrote more about this; both mistakenly cited Cicero as a stoic.

In 1967, becoming active again at University of Pennsylvania, Beck still described himself and his new therapy (as he always would quietly) as neo-Freudian in the ego psychology school, albeit focused on interactions with the environment rather than internal drives. He offered cognitive therapy work as a relatively "neutral" space and a bridge to psychology. With a monograph on depression that Beck published in 1967, according to historian Rachael Rosner: "Cognitive Therapy entered the marketplace as a corrective experimentalist psychological framework both for himself and his patients and for his fellow psychiatrists."

Working with depressed patients, Beck found that they experienced streams of negative thoughts that seemed to arise spontaneously. He termed these cognitions "automatic thoughts", and discovered that their content fell into three categories: negative ideas about oneself, the world, and the future. He stated that such cognitions were interrelated as the cognitive triad. Limited time spent reflecting on automatic thoughts would lead patients to treat them as valid.

Beck began helping patients identify and evaluate these thoughts and found that by doing so, patients were able to think more realistically, which led them to feel better emotionally and behave more functionally. He developed key ideas in CBT, explaining that different disorders were associated with different types of distorted thinking. Distorted thinking has a negative effect on a person's behaviour no matter what type of disorder they had, he found. Beck explained that successful interventions will educate a person to understand and become aware of their distorted thinking, and how to challenge its effects. He discovered that frequent negative automatic thoughts reveal a person's core beliefs. He explained that core beliefs are formed over lifelong experiences; we "feel" these beliefs to be true.

Since that time, Beck and his colleagues worldwide have researched the efficacy of this form of psychotherapy in treating a wide variety of disorders including depression, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, drug abuse, anxiety disorders, personality disorders, and many other medical conditions with psychological components. Cognitive therapy has also been applied with success to individuals with anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, and many other medical and psychiatric disorders. Some of Beck's most recent work has focused on cognitive therapy for schizophrenia, borderline personality disorder, and for patients who have had recurrent suicide attempts.

Beck's recent research on the treatment of schizophrenia has suggested that patients once believed to be non-responsive to treatment are amenable to positive change. Even the most severe presentations of the illness, such as those involving long periods of hospitalization, bizarre behavior, poor personal hygiene, self-injury, and aggressiveness, can respond positively to a modified version of cognitive behavioural treatment. Called recovery-oriented cognitive therapy (CT-R), the approach focused less on the amelioration of symptoms, but instead, on empowering the individual to identify and attain meaningful goals and a desired life.

However, some mental health professionals have opposed Beck's cognitive models and resulting therapies as too mechanistic or too limited in which parts of mental activity they will consider. From within the CBT community itself, one line of research using component analyses (dismantling studies) has found that the addition of cognitive strategies often fails to show superior efficacy over behavioral strategies alone, and that attempts to challenge thoughts can sometimes have a rebound effect. Moreover, although Beck's work was presented as a far more scientific and experimentally-based development than psychoanalysis (while being less reductive than behaviourism), Beck's key principles were not necessarily based on the general findings and models of cognitive psychology or neuroscience developing at that time but were derived from personal clinical observations and interpretations in his therapy office. And although there have been many cognitive models developed for different mental disorders and hundreds of outcome studies on the effectiveness of CBT—relatively easy because of the narrow, time-limited and manual-based nature of the treatment—there has been much less focus on experimentally proving the supposedly active mechanisms; in some cases the predicted causal relationships have not been found, such as between dysfunctional attitudes and outcomes.

In 2017, Medscape named Beck the fourth most influential physician in the past century.

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement