By Dwight Jon Zimmerman - November 15, 2020

Military patients in an emergency hospital in Camp Funston, Kansas, in the midst of the Spanish flu pandemic. Camp Funston recorded the first military case of the Spanish flu on March 4, 1918.

Military patients in an emergency hospital in Camp Funston, Kansas, in the midst of the Spanish flu pandemic. Camp Funston recorded the first military case of the Spanish flu on March 4, 1918. National Museum of Health and Medicine photo

THE PANDEMIC BEGINS

On March 4, 1918, Pvt. Albert Gitchell, a cook at Camp Funston in the Fort Riley, Kansas military reservation, was admitted to sick bay, the diagnosis: flu. His was the first recorded military case of what would come to be called the Spanish flu, one that, when it had run its course, would infect hundreds of millions of people worldwide and kill more than 50 million.

Though contagious, because the cases were mild – and with the French and British armies in desperate need of fresh troops from their new ally the United States in order to finally bring to an end the Great War (World War I) – Fort Riley’s commander ordered the flow of men entering and leaving for Army bases throughout the country to continue uninterrupted. Only flu victims requiring hospitalization were exempt.

How did the Camp Funston Patient Zero story get started?

The search continues for the origin of the Spanish Flu Patient Zero narrative. Every time I read the story — and it’s ubiquitous — there’s the same cluster of details with nary a citation of the source. Albert Gitchell, or in some accounts Mitchell, was a cook at Camp Funston (or Fort Riley), Kansas, who fell ill on March 11, 1918 (in some accounts March 4) and reported to the infirmary first thing, followed shortly by others named, and then a hundred, all with the same complaints of fever, lassitude and headaches.

Seeking the earliest mention of Patient Zero Albert Gitchell, I have in hand what I believe to be the first general history of the pandemic, The Great Epidemic: When the Spanish Influenza Struck by A. A. Hoehling (Boston: Little, Brown & Co, 1961).

It gives a detailed account of the March 11 outbreak at Camp Funston, though with not the clearest paper trail. The sources appear to include the admission book from the hospital, or some other list with comments, or actual medical charts (much less likely). Elizabeth Harding, RN, ANC (Ret.), at the time a 2nd Lieutenant and the head nurse at the Fort Riley hospital, is a possible source — but not, I think, “Surgeon Schreiner,” that is, Colonel Edward R. Schreiner, MD, AMC, officer in charge of Fort Riley hospital. More on them in a moment. Here’s the whole story as told on pp. 14-15 in The Great Epidemic:

On Monday morning, March 11, before breakfast time, the duty sergeant at Hospital Building 91, once host to the sickened backwash of the Spanish-American War, had a caller. Albert Gitchell, a company cook, complained of a “bad cold.” He was feverish, suffered from a sore throat, headache and muscular pains. Gitchell was quickly banished to a contagious ward. Hardly had a corpsman put a thermometer in the soldier’s mouth when Corporal Lee W. Drake from the First Battalion, Headquarters Transportation Detachment, reported to the same admitting desk in Building 91. His symptoms, even to a 103° fever, were identical with Gitchell’s.

Two cases with a rubber stamp similarity could have been coincidence. However, when Sergeant Adolph Hurby came coughing in moments later, the duty corpsman called for the chief nurse. By the time Lieutenant Harding had arrived at Building 91 two other sick soldiers were awaiting admission. Miss Harding knew she was confronted with a potentially grave situation. She cranked the wall phone. ‘Colonel,’ she commenced with concern.

Surgeon Schreiner, a sober, meticulous officer, did not wait to shave, comb his mustache, or even snap the hooks and eyes of his uniform’s choker collar. He hurried out of his quarters and shook the nodding driver of his motorcycle and sidecar, which was always standing by. Soon he was examining his first patient, shortly, his second, his third, and so on. By breakfast time, the telltale medical manifestations were as obvious to [15] Colonel Schreiner as the inscriptions in a family Bible. With the aid of his assistants, he was noting on chart after chart, except for minor variations:

Fever 104°. Low pulse, drowsiness and photophobia. Conjunctivae reddened and mucous membranes of nose, throat and bronchi, evidence of inflammation.

There was little doubt in Dr. Schreiner’s mind that the Army post had been hit with influenza. By noon, 107 patients had been admitted to the hospital.

Surgeon Schreiner figures nowhere in the Acknowledgements or Bibliography sections of the book. Yet how boldly he is drawn! including the workings of his mind! Is that what is called creative non-fiction? But there is nothing there that could not be realized with the aid of Col. Schreiner’s picture and someone’s description of his behaviour; likely also his correspondence on the state of the camp. Nurse Harding does show up in the “indebted to the following people” section at the back of The Great Epidemic. Even though there’s no mention of hospital admission documents, I conclude that the writer engaged his flair for drama to work up some hospital admissions document. Thus far I haven’t been able to get anywhere near such a document. Or to Dr. Schreiner.

A history of Fort Riley hospital published in the 1950s(1) relates that Elizabeth Harding attained the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. In a letter extensively quoted,(2) Harding related that she arrived at Fort Riley in a snowstorm in October 1917 and suffered the utmost privation that winter, along with thousands of doughboys. She was there when the spring wave of epidemic influenza struck but, tellingly, doesn’t mention it — meningitis was of the greatest concern. Which suggests to me that she was not the source of the Gitchell story that The Great Epidemic recounted three years later.

(1) “An Army Hospital: From Horses to Helicopters: Fort Riley, 1904-1957” by George E. Omer Jr., in Kansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. 24, No. 1, Spring 1958, pp. 57-78. Accessed via the Kansas Historical Society website. ❡ (2) “Letter to Major Judd, chief nurse, U. S. A. H., Fort Riley, from Elizabeth Harding, 30 Park Ave., Apt. 3-D, New York 16, N. Y.”

Incidentally, Lieut. Harding was there as the deadly “second wave” of influenza rolled over Kansas later in 1918:

I left Fort Riley in October of 1918, for duty in the Office of the Surgeon General. The flu epidemic had just struck, and the day I left there were over 5,000 patients. Barracks were opened at Camp Funston to accommodate the sick. Several nurses died, I am not certain, but it seems to me at least sixteen. The nurses who had been on duty at Fort Riley stood up very well, but nurses who were rushed in for the emergency were hard hit, and arrived sick.*

Sixteen nurses down in one camp. The brutality of the epidemic is inconceivable.

Strange to relate, in Albert Gitchell’s personal and family history in online records, there is not the merest mention of the Patient Zero narrative.* Nor, to be candid, could I find anything that directly links the person I found online to Camp Funston. I do find an Albert Martin Gitchell working in food-and-drink-related occupations before and after the war, and I believe that man to be the Albert Gitchell, a cook at Camp Funston who famously got sick on March 11, 1918.

* Documents accessed via ancestry.com; news articles with the newspapers.com search engine.

The draft registration card for Albert Martin Gitchell reveals he was born in Chicago in 1890 and was in 1917 a self-employed butcher living in Ree Heights, South Dakota. His father, Albert W., was a plumber (1910 census), and his grandfather William, a carpenter; Albert’s mother Ellen was from Norway. On his military gravestone are carved Albert’s rank, Sergeant; his unit, 9 Co[mpany] 3 B[attalion], 164 Depot Brigade; and his service in World War I. A 1919 record memorialized Albert’s marriage to Emma Van Gorp, a widow; both residents of Ree Heights. The 1920 census for Ree Heights Township identifies him as a restaurant proprietor and Emma as the daughter of immigrants (elsewhere named Puffer) from Bohemia (now Czech Republic). The Gitchells apparently lived in a Bohemian enclave. For a time they lived in Binghampton, New York. In 1930 Albert was a commercial traveler for a gas and electric company there, and Emma worked at film casting in a factory. A 1935 issue of the Huron, SD Daily Plainsman reported that A. Gitchell of Ree Heights was issued a high point beer license. In 1945 the Gitchells moved to Sturgis, SD, where they operated a neighbourhood store until 1951. The Gitchells evidently did not have children.

A spread in the Rapid City [SD] Journal of November 30, 1958 featured the South Dakota State Soldiers’ Home, where Mr. and Mrs. Albert Gitchell were depicted in their suite.

Albert died in 1968. Emma lived at the State Home until her death in 1977.

After The Great Epidemic was published in 1961, a syndicated review of the book by William R. Lansberg appeared in small-town New York newspapers; it mentioned Patient Zero Albert Gitchell. After that the earliest newspaper account I could find was an article in the September 6, 1976 Dayton, Ohio Journal Herald, “20 million died in 1918-’19 outbreak. Swine flu resurrects fear of pandemic.” The writer of that, Hugh McCann, of the Detroit News, demonized Gitchell, claiming he “won immortality as the man whose sneeze went around the world, causing the worst plague in the history of man.” The next mention of Patient Zero Gitchell I could find was in March 1998, in a staff-written story in The Manhattan [Kansas] Mercury. Since then, the floodgates have definitely opened. Albert Gitchell has had way more than his fifteen minutes of fame. But immortality? C’mon.

If one thing is clear in all this, it’s that the origin of the Spanish Flu virus and the identity of Patient Zero will always be mysterious.

PS: Albert Gitchell had no inkling, I am sure, that he was Patient Zero. Anyway, he was not Patient Zero. Because Patient Zero was a construction. And because Albert just wasn’t Patient Zero. The Opie medical commission the army sent to Camp Funston in July 1918 reported that the same disease had been endemic at the camp since it opened the previous September.*

By Dwight Jon Zimmerman - November 15, 2020

Military patients in an emergency hospital in Camp Funston, Kansas, in the midst of the Spanish flu pandemic. Camp Funston recorded the first military case of the Spanish flu on March 4, 1918.

Military patients in an emergency hospital in Camp Funston, Kansas, in the midst of the Spanish flu pandemic. Camp Funston recorded the first military case of the Spanish flu on March 4, 1918. National Museum of Health and Medicine photo

THE PANDEMIC BEGINS

On March 4, 1918, Pvt. Albert Gitchell, a cook at Camp Funston in the Fort Riley, Kansas military reservation, was admitted to sick bay, the diagnosis: flu. His was the first recorded military case of what would come to be called the Spanish flu, one that, when it had run its course, would infect hundreds of millions of people worldwide and kill more than 50 million.

Though contagious, because the cases were mild – and with the French and British armies in desperate need of fresh troops from their new ally the United States in order to finally bring to an end the Great War (World War I) – Fort Riley’s commander ordered the flow of men entering and leaving for Army bases throughout the country to continue uninterrupted. Only flu victims requiring hospitalization were exempt.

How did the Camp Funston Patient Zero story get started?

The search continues for the origin of the Spanish Flu Patient Zero narrative. Every time I read the story — and it’s ubiquitous — there’s the same cluster of details with nary a citation of the source. Albert Gitchell, or in some accounts Mitchell, was a cook at Camp Funston (or Fort Riley), Kansas, who fell ill on March 11, 1918 (in some accounts March 4) and reported to the infirmary first thing, followed shortly by others named, and then a hundred, all with the same complaints of fever, lassitude and headaches.

Seeking the earliest mention of Patient Zero Albert Gitchell, I have in hand what I believe to be the first general history of the pandemic, The Great Epidemic: When the Spanish Influenza Struck by A. A. Hoehling (Boston: Little, Brown & Co, 1961).

It gives a detailed account of the March 11 outbreak at Camp Funston, though with not the clearest paper trail. The sources appear to include the admission book from the hospital, or some other list with comments, or actual medical charts (much less likely). Elizabeth Harding, RN, ANC (Ret.), at the time a 2nd Lieutenant and the head nurse at the Fort Riley hospital, is a possible source — but not, I think, “Surgeon Schreiner,” that is, Colonel Edward R. Schreiner, MD, AMC, officer in charge of Fort Riley hospital. More on them in a moment. Here’s the whole story as told on pp. 14-15 in The Great Epidemic:

On Monday morning, March 11, before breakfast time, the duty sergeant at Hospital Building 91, once host to the sickened backwash of the Spanish-American War, had a caller. Albert Gitchell, a company cook, complained of a “bad cold.” He was feverish, suffered from a sore throat, headache and muscular pains. Gitchell was quickly banished to a contagious ward. Hardly had a corpsman put a thermometer in the soldier’s mouth when Corporal Lee W. Drake from the First Battalion, Headquarters Transportation Detachment, reported to the same admitting desk in Building 91. His symptoms, even to a 103° fever, were identical with Gitchell’s.

Two cases with a rubber stamp similarity could have been coincidence. However, when Sergeant Adolph Hurby came coughing in moments later, the duty corpsman called for the chief nurse. By the time Lieutenant Harding had arrived at Building 91 two other sick soldiers were awaiting admission. Miss Harding knew she was confronted with a potentially grave situation. She cranked the wall phone. ‘Colonel,’ she commenced with concern.

Surgeon Schreiner, a sober, meticulous officer, did not wait to shave, comb his mustache, or even snap the hooks and eyes of his uniform’s choker collar. He hurried out of his quarters and shook the nodding driver of his motorcycle and sidecar, which was always standing by. Soon he was examining his first patient, shortly, his second, his third, and so on. By breakfast time, the telltale medical manifestations were as obvious to [15] Colonel Schreiner as the inscriptions in a family Bible. With the aid of his assistants, he was noting on chart after chart, except for minor variations:

Fever 104°. Low pulse, drowsiness and photophobia. Conjunctivae reddened and mucous membranes of nose, throat and bronchi, evidence of inflammation.

There was little doubt in Dr. Schreiner’s mind that the Army post had been hit with influenza. By noon, 107 patients had been admitted to the hospital.

Surgeon Schreiner figures nowhere in the Acknowledgements or Bibliography sections of the book. Yet how boldly he is drawn! including the workings of his mind! Is that what is called creative non-fiction? But there is nothing there that could not be realized with the aid of Col. Schreiner’s picture and someone’s description of his behaviour; likely also his correspondence on the state of the camp. Nurse Harding does show up in the “indebted to the following people” section at the back of The Great Epidemic. Even though there’s no mention of hospital admission documents, I conclude that the writer engaged his flair for drama to work up some hospital admissions document. Thus far I haven’t been able to get anywhere near such a document. Or to Dr. Schreiner.

A history of Fort Riley hospital published in the 1950s(1) relates that Elizabeth Harding attained the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. In a letter extensively quoted,(2) Harding related that she arrived at Fort Riley in a snowstorm in October 1917 and suffered the utmost privation that winter, along with thousands of doughboys. She was there when the spring wave of epidemic influenza struck but, tellingly, doesn’t mention it — meningitis was of the greatest concern. Which suggests to me that she was not the source of the Gitchell story that The Great Epidemic recounted three years later.

(1) “An Army Hospital: From Horses to Helicopters: Fort Riley, 1904-1957” by George E. Omer Jr., in Kansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. 24, No. 1, Spring 1958, pp. 57-78. Accessed via the Kansas Historical Society website. ❡ (2) “Letter to Major Judd, chief nurse, U. S. A. H., Fort Riley, from Elizabeth Harding, 30 Park Ave., Apt. 3-D, New York 16, N. Y.”

Incidentally, Lieut. Harding was there as the deadly “second wave” of influenza rolled over Kansas later in 1918:

I left Fort Riley in October of 1918, for duty in the Office of the Surgeon General. The flu epidemic had just struck, and the day I left there were over 5,000 patients. Barracks were opened at Camp Funston to accommodate the sick. Several nurses died, I am not certain, but it seems to me at least sixteen. The nurses who had been on duty at Fort Riley stood up very well, but nurses who were rushed in for the emergency were hard hit, and arrived sick.*

Sixteen nurses down in one camp. The brutality of the epidemic is inconceivable.

Strange to relate, in Albert Gitchell’s personal and family history in online records, there is not the merest mention of the Patient Zero narrative.* Nor, to be candid, could I find anything that directly links the person I found online to Camp Funston. I do find an Albert Martin Gitchell working in food-and-drink-related occupations before and after the war, and I believe that man to be the Albert Gitchell, a cook at Camp Funston who famously got sick on March 11, 1918.

* Documents accessed via ancestry.com; news articles with the newspapers.com search engine.

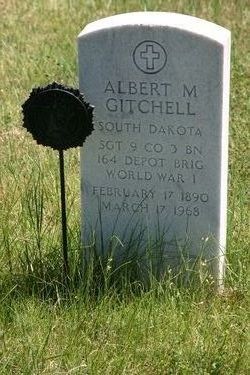

The draft registration card for Albert Martin Gitchell reveals he was born in Chicago in 1890 and was in 1917 a self-employed butcher living in Ree Heights, South Dakota. His father, Albert W., was a plumber (1910 census), and his grandfather William, a carpenter; Albert’s mother Ellen was from Norway. On his military gravestone are carved Albert’s rank, Sergeant; his unit, 9 Co[mpany] 3 B[attalion], 164 Depot Brigade; and his service in World War I. A 1919 record memorialized Albert’s marriage to Emma Van Gorp, a widow; both residents of Ree Heights. The 1920 census for Ree Heights Township identifies him as a restaurant proprietor and Emma as the daughter of immigrants (elsewhere named Puffer) from Bohemia (now Czech Republic). The Gitchells apparently lived in a Bohemian enclave. For a time they lived in Binghampton, New York. In 1930 Albert was a commercial traveler for a gas and electric company there, and Emma worked at film casting in a factory. A 1935 issue of the Huron, SD Daily Plainsman reported that A. Gitchell of Ree Heights was issued a high point beer license. In 1945 the Gitchells moved to Sturgis, SD, where they operated a neighbourhood store until 1951. The Gitchells evidently did not have children.

A spread in the Rapid City [SD] Journal of November 30, 1958 featured the South Dakota State Soldiers’ Home, where Mr. and Mrs. Albert Gitchell were depicted in their suite.

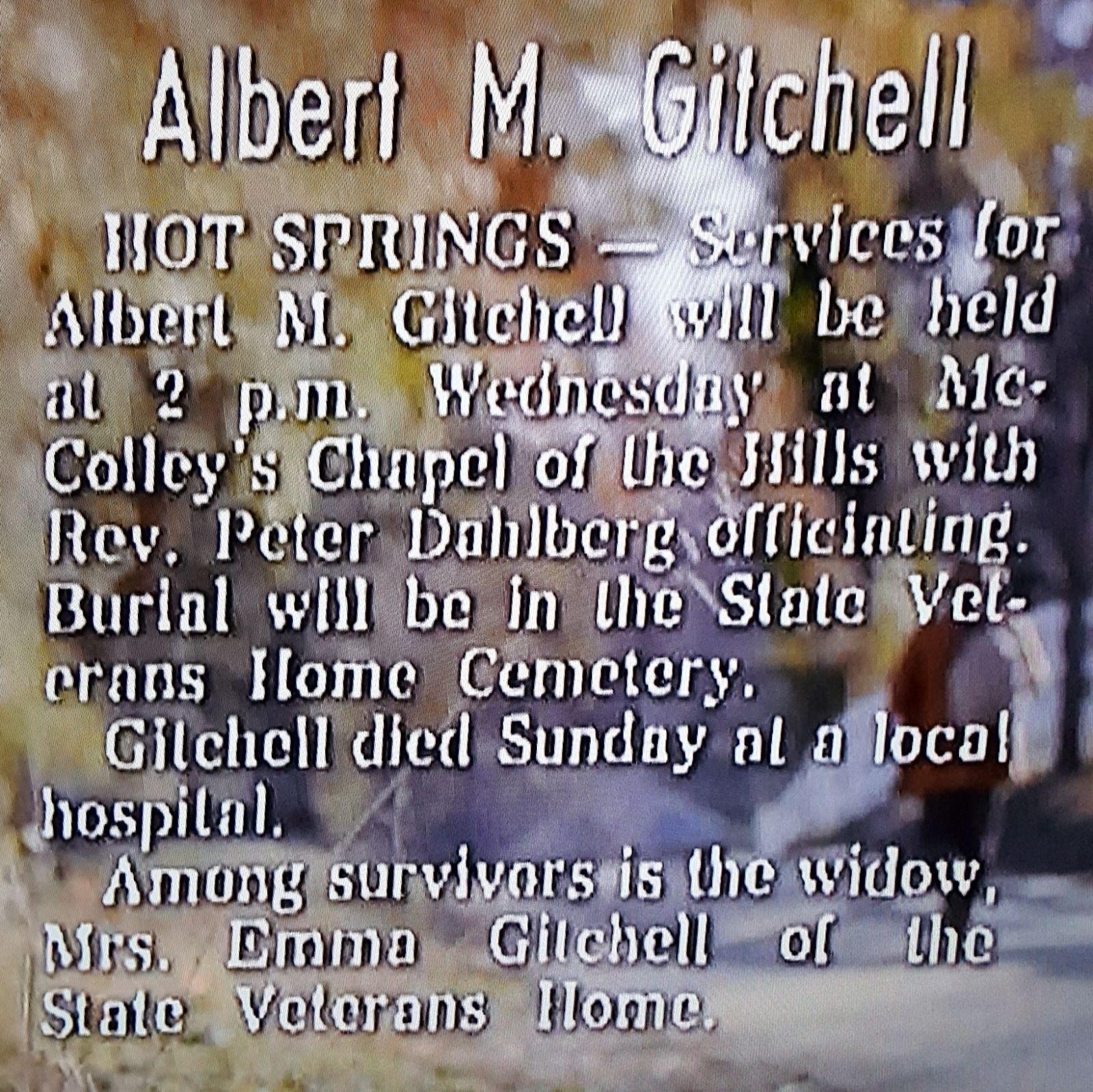

Albert died in 1968. Emma lived at the State Home until her death in 1977.

After The Great Epidemic was published in 1961, a syndicated review of the book by William R. Lansberg appeared in small-town New York newspapers; it mentioned Patient Zero Albert Gitchell. After that the earliest newspaper account I could find was an article in the September 6, 1976 Dayton, Ohio Journal Herald, “20 million died in 1918-’19 outbreak. Swine flu resurrects fear of pandemic.” The writer of that, Hugh McCann, of the Detroit News, demonized Gitchell, claiming he “won immortality as the man whose sneeze went around the world, causing the worst plague in the history of man.” The next mention of Patient Zero Gitchell I could find was in March 1998, in a staff-written story in The Manhattan [Kansas] Mercury. Since then, the floodgates have definitely opened. Albert Gitchell has had way more than his fifteen minutes of fame. But immortality? C’mon.

If one thing is clear in all this, it’s that the origin of the Spanish Flu virus and the identity of Patient Zero will always be mysterious.

PS: Albert Gitchell had no inkling, I am sure, that he was Patient Zero. Anyway, he was not Patient Zero. Because Patient Zero was a construction. And because Albert just wasn’t Patient Zero. The Opie medical commission the army sent to Camp Funston in July 1918 reported that the same disease had been endemic at the camp since it opened the previous September.*

Inscription

SOUTH DAKOTA

SGT 9 CO 3 BN

164 DEPOT BRIG

WORLD WAR I