The 'Law Times' acidly commented that promotion to the Bench no longer seemed to depend entirely upon merit. But it thought, and the rest of the legal press, agreed, that Lawrence would probably make a good enough Judge nonetheless. Lawrence did not really live up to even these limited expectations. His handful of Commercial Court cases in 1919-1920 were as immemorable as the rest of his body of work. Italian State Railways v Mavrogordatos [1919] 2 KB 305 remains a significant decision on what is involved in "redelivery" under a time charter, though Lawrence was helping out in the Court of Appeal in that case, not sitting in the Commercial Court. His most memorable case was R v Casement (1917) 12 Cr App Rep 99, in which he was one of five Commercial Judges (the others were Darling, Bray, Scrutton, and Atkin) who dismissed Sir Roger Casement's appeal from his conviction for treason.

By the beginning of 1921, Lawrence had been on the Bench for sixteen years and was fast approaching his eighties. He had been overlooked for promotion to the Court of Appeal on half a dozen occasions, and it was obvious that he would never go any further. Then fate took a hand.

The Earl of Reading, formerly Commercial Court practitioner Rufus Isaacs KC, had been Lord Chief Justice since 1913. He had never been entirely happy in the role. Isaacs had always felt ambivalent about giving up his political career as a Liberal MP and Attorney-General, and he had relished a return to politics during the Great War, when he took leave of absence from his judicial role to act as commissioner and then ambassador to the United States. Isaacs missed the glamour of international diplomacy when he had to return to the Bench at the end of the War. When the post of Viceroy of India fell vacant, he angled for the opportunity for another frontline political role, and Prime Minister Lord George granted his wish.

The news that the Queen's Bench was going to need a new Chief Justice was announced in January 1921. There was then an unseemly delay in naming a successor. By political convention, the Attorney-General of the day, whether or not evidencing any signs of judicial potential, was entitled to claim an empty Chief Justiceship. Liberal Attorney-General Gordon Hewart wanted the job. Lloyd George was eager to oblige. But Lloyd George believed that he needed Hewart in the Commons. The situation should have been chalked up to Hewart's bad luck and bad timing, with a capable Chief Justice appointed from the Bench: the legal press speculated about Lord Sterndale or Lord Sumner. But Lloyd George did not want to disappoint a colleague, and he came up with a cunning solution. He offered the Chief Justiceship to Lawrence, on condition that Lawrence must sign an undated letter of resignation, to be released at a date of Lloyd George's choosing. Lloyd George notoriously struggled with such sophisticated concepts as right and wrong, so it is not particularly surprising that he should make such an offer. What is extraordinary is that not only did Lawrence accept this squalid deal, but he had to fight off competition: fellow Queen's Bench Judge Charles Darling made clear to Hewart that he would be more than willing to serve as a stopgap Chief Justice, even, he said, if only for ten minutes. Darling, who was seventy-one, speculated later that he had been too young to suit Lloyd George's purpose. At all events, the position went to Lawrence, who was six years older and so deaf that he could no longer follow cases properly.

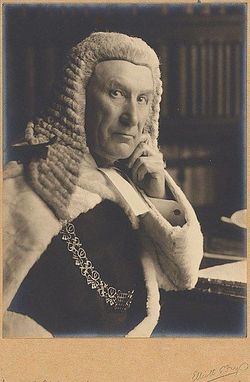

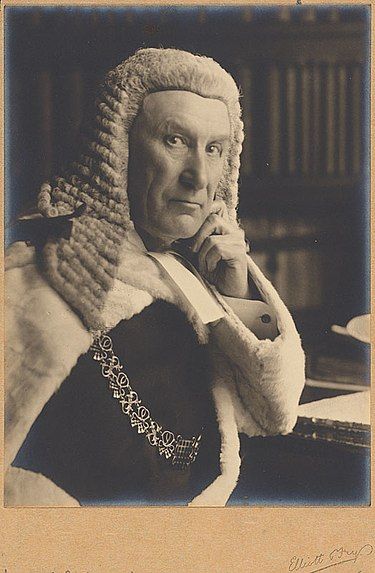

The 'Times' photographed the swearing-in on 15th April 1921: an unenthusiastic Lord Chancellor Birkenhead (who privately condemned the whole affair as unlawful) presiding in the centre; Lawrence on his left.

Little attempt was made to conceal what was going on. When Lawrence first took his seat in Court after being sworn-in in April 1921, Hewart made a speech of welcome on behalf of the Bar. In his reply, Lawrence candidly acknowledged that it should have been Hewart who was taking office. The legal press had no illusions that Lawrence's appointment to the head of the Queen's Bench at the age of seventy-seven was anything other an act of short-term political expediency.

Lawrence's tenure as an impostorous Chief Justice was short indeed. Lloyd George sacked him less than a year later, releasing the resignation letter in early March 1922 and appointing Hewart to the position which he craved. Lawrence was said to have read about his own resignation in the paper in the back of his morning taxi: he left home Lord Chief Justice, and arrived at the Law Courts unemployed. The sordid saga, which was subsequently exacerbated by Hewart's shameless incompetence as Chief Justice, may have had the beneficial effect of hastening the end of the corrupt practice of treating the office as an automatic reward for time-served Law Officers. Hewart's successor, Thomas Inskip, was the last former Attorney-General to become Chief Justice.

Already nearly eighty when he was fired, Lawrence enjoyed a lengthy and active retirement. Into his nineties, he enjoyed his favourite pastime of salmon fishing on the River Wye. (Lawrence liked being outdoors: he had ridden to hounds as a young man, and played golf in middle age.) On 3rd August 1936, trying his fortune on an unfamiliar stretch of the river, he stumbled, fell into the cold water, and died of a heart attack.

Lawrence had married his cousin, Jessie Lawrence, in 1875, and they had four sons and a daughter. The third son, Geoffrey, became a King's Bench Judge in 1932. He performed with some distinction as the principal British Judge at the Nuremburg War Trials, but his appointment as Lord of Appeal by way of reward (as Lord Oaksey) proved to be another case of over-promotion.

The 'Law Times' acidly commented that promotion to the Bench no longer seemed to depend entirely upon merit. But it thought, and the rest of the legal press, agreed, that Lawrence would probably make a good enough Judge nonetheless. Lawrence did not really live up to even these limited expectations. His handful of Commercial Court cases in 1919-1920 were as immemorable as the rest of his body of work. Italian State Railways v Mavrogordatos [1919] 2 KB 305 remains a significant decision on what is involved in "redelivery" under a time charter, though Lawrence was helping out in the Court of Appeal in that case, not sitting in the Commercial Court. His most memorable case was R v Casement (1917) 12 Cr App Rep 99, in which he was one of five Commercial Judges (the others were Darling, Bray, Scrutton, and Atkin) who dismissed Sir Roger Casement's appeal from his conviction for treason.

By the beginning of 1921, Lawrence had been on the Bench for sixteen years and was fast approaching his eighties. He had been overlooked for promotion to the Court of Appeal on half a dozen occasions, and it was obvious that he would never go any further. Then fate took a hand.

The Earl of Reading, formerly Commercial Court practitioner Rufus Isaacs KC, had been Lord Chief Justice since 1913. He had never been entirely happy in the role. Isaacs had always felt ambivalent about giving up his political career as a Liberal MP and Attorney-General, and he had relished a return to politics during the Great War, when he took leave of absence from his judicial role to act as commissioner and then ambassador to the United States. Isaacs missed the glamour of international diplomacy when he had to return to the Bench at the end of the War. When the post of Viceroy of India fell vacant, he angled for the opportunity for another frontline political role, and Prime Minister Lord George granted his wish.

The news that the Queen's Bench was going to need a new Chief Justice was announced in January 1921. There was then an unseemly delay in naming a successor. By political convention, the Attorney-General of the day, whether or not evidencing any signs of judicial potential, was entitled to claim an empty Chief Justiceship. Liberal Attorney-General Gordon Hewart wanted the job. Lloyd George was eager to oblige. But Lloyd George believed that he needed Hewart in the Commons. The situation should have been chalked up to Hewart's bad luck and bad timing, with a capable Chief Justice appointed from the Bench: the legal press speculated about Lord Sterndale or Lord Sumner. But Lloyd George did not want to disappoint a colleague, and he came up with a cunning solution. He offered the Chief Justiceship to Lawrence, on condition that Lawrence must sign an undated letter of resignation, to be released at a date of Lloyd George's choosing. Lloyd George notoriously struggled with such sophisticated concepts as right and wrong, so it is not particularly surprising that he should make such an offer. What is extraordinary is that not only did Lawrence accept this squalid deal, but he had to fight off competition: fellow Queen's Bench Judge Charles Darling made clear to Hewart that he would be more than willing to serve as a stopgap Chief Justice, even, he said, if only for ten minutes. Darling, who was seventy-one, speculated later that he had been too young to suit Lloyd George's purpose. At all events, the position went to Lawrence, who was six years older and so deaf that he could no longer follow cases properly.

The 'Times' photographed the swearing-in on 15th April 1921: an unenthusiastic Lord Chancellor Birkenhead (who privately condemned the whole affair as unlawful) presiding in the centre; Lawrence on his left.

Little attempt was made to conceal what was going on. When Lawrence first took his seat in Court after being sworn-in in April 1921, Hewart made a speech of welcome on behalf of the Bar. In his reply, Lawrence candidly acknowledged that it should have been Hewart who was taking office. The legal press had no illusions that Lawrence's appointment to the head of the Queen's Bench at the age of seventy-seven was anything other an act of short-term political expediency.

Lawrence's tenure as an impostorous Chief Justice was short indeed. Lloyd George sacked him less than a year later, releasing the resignation letter in early March 1922 and appointing Hewart to the position which he craved. Lawrence was said to have read about his own resignation in the paper in the back of his morning taxi: he left home Lord Chief Justice, and arrived at the Law Courts unemployed. The sordid saga, which was subsequently exacerbated by Hewart's shameless incompetence as Chief Justice, may have had the beneficial effect of hastening the end of the corrupt practice of treating the office as an automatic reward for time-served Law Officers. Hewart's successor, Thomas Inskip, was the last former Attorney-General to become Chief Justice.

Already nearly eighty when he was fired, Lawrence enjoyed a lengthy and active retirement. Into his nineties, he enjoyed his favourite pastime of salmon fishing on the River Wye. (Lawrence liked being outdoors: he had ridden to hounds as a young man, and played golf in middle age.) On 3rd August 1936, trying his fortune on an unfamiliar stretch of the river, he stumbled, fell into the cold water, and died of a heart attack.

Lawrence had married his cousin, Jessie Lawrence, in 1875, and they had four sons and a daughter. The third son, Geoffrey, became a King's Bench Judge in 1932. He performed with some distinction as the principal British Judge at the Nuremburg War Trials, but his appointment as Lord of Appeal by way of reward (as Lord Oaksey) proved to be another case of over-promotion.

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement