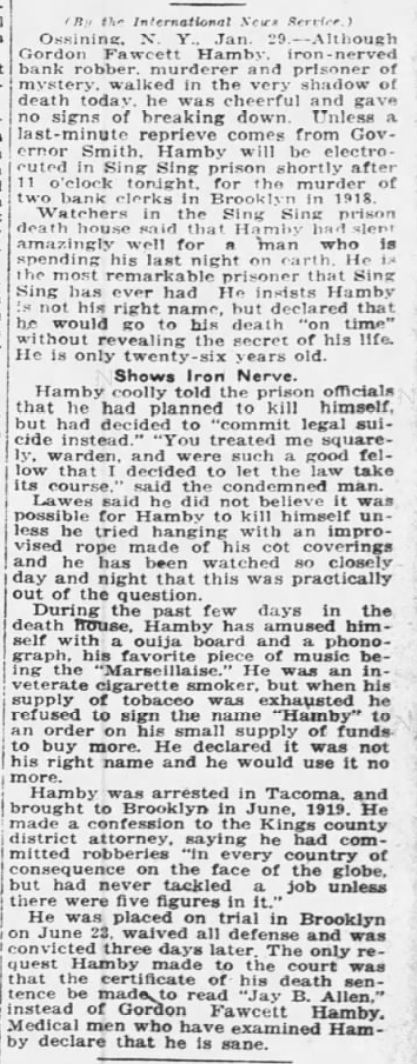

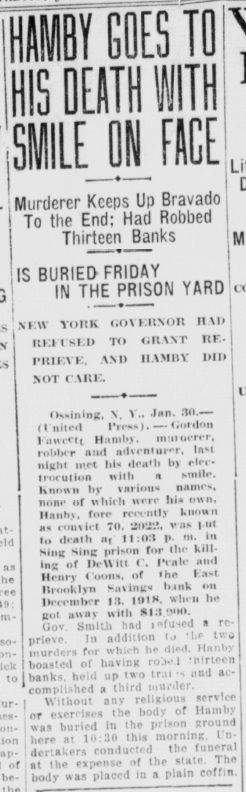

Hamby was of unusual interest to criminologists. He fought against being extradited when he was captured in the West. But when he finally was brought back to New York and identified as the bank robber he took refuge in fatalism. From then on he did not display the slightest emotion. He asked that his trial be hurried, he requested the judge to sentence him to death at once and he forbade his attorneys to take an appeal from the verdict of the Jury.

“I committed the crimes,” he said; “it is right that I should pay the penalty.”

Hamby’s conduct was so strange that a lunacy commission was appointed to inquire into his sanity. The commission reported that Hamby had been unusually well educated, that he had a brilliant mentality and that his mind was better and clearer than that of the majority of men.

There was not the slightest doubt that he was sane.

Hamby was cheerful all during the time that he was waiting in the death house to be executed, even to his last day.

On the morning of the day of his execution Hamby was visited by both the Protestant and the Catholic chaplains of the prison, hut he asked that neither of them accompany him to the chair.

“It seems such mockery,” Hamby told the chaplains, “after the life that I have been leading to go to the chair with a priest or a minister by my side. Let me walk alone.”

Last Hour Spent With Ouija Board

The bandit and self-confessed murderer spent his last hour playing with the ouija hoard, and when the keepers came to lead him to his execution he jumped up, saluted them with a flourish and said:

“I’ll be right with you!”

He calmly lighted a cigarette, stuck both hands in his pockets and actually swaggered down the corridor, He never faltered when he came in sight of the little green door, the sight that had unnerved so many men before him. He came on steadily and confidently, puffing calmly on the cigarette, and bowing cheerfully as he entered to the newspaper men and the other official witnesses who sat silently on the wooden benches facing the electric chair. Hamby stopped before the chair, pinched the fire from his cigarette, and spoke to the warden:

“May I say a word?”

“Certainly,” replied the warden, “anything you like.”

“Thank you,” said Hamby. He turned to the witnesses.

“I Just want to say. gentlemen, that any man who stood in front of Jay B. Allen’s gun had a chance. That’s all ”

He sat calmly in the chair and motioned to the guards.

“Go ahead, boys!”

The guards busied themselves adjusting the electrodes and the straps and the prison physician came nearer to see that everything was done properly. Hamby noticed him and smiled.

“Where is the red handkerchief, Doc?” he asked.

This referred to a joke, as he termed it, which he had been having with the physician. He had suggested that the latter obtain a new, bright red bandana handkerchief with which to signal the electrician when everything was ready for throwing the switch.

And these were the last words that Hamby ever spoke.

The doctor made an almost imperceptible motion with his hand; behind the curtain the electrician threw the switch, there was a low humming sound and Gordon Fawcett Hamby was dead with a smile on his face and a joke on his lips.

He was young, somewhere in the early twenties, but he left behind him a criminal record that has been equaled by few. Guards who had been at Sing Sing for many years and who have seen many men die say that Hamby faced the electric chair more courageously than any other man who ever passed through the little green door, with the possible exception of two—Carlyle Harris and Sam Haynes.

Hamby was of unusual interest to criminologists. He fought against being extradited when he was captured in the West. But when he finally was brought back to New York and identified as the bank robber he took refuge in fatalism. From then on he did not display the slightest emotion. He asked that his trial be hurried, he requested the judge to sentence him to death at once and he forbade his attorneys to take an appeal from the verdict of the Jury.

“I committed the crimes,” he said; “it is right that I should pay the penalty.”

Hamby’s conduct was so strange that a lunacy commission was appointed to inquire into his sanity. The commission reported that Hamby had been unusually well educated, that he had a brilliant mentality and that his mind was better and clearer than that of the majority of men.

There was not the slightest doubt that he was sane.

Hamby was cheerful all during the time that he was waiting in the death house to be executed, even to his last day.

On the morning of the day of his execution Hamby was visited by both the Protestant and the Catholic chaplains of the prison, hut he asked that neither of them accompany him to the chair.

“It seems such mockery,” Hamby told the chaplains, “after the life that I have been leading to go to the chair with a priest or a minister by my side. Let me walk alone.”

Last Hour Spent With Ouija Board

The bandit and self-confessed murderer spent his last hour playing with the ouija hoard, and when the keepers came to lead him to his execution he jumped up, saluted them with a flourish and said:

“I’ll be right with you!”

He calmly lighted a cigarette, stuck both hands in his pockets and actually swaggered down the corridor, He never faltered when he came in sight of the little green door, the sight that had unnerved so many men before him. He came on steadily and confidently, puffing calmly on the cigarette, and bowing cheerfully as he entered to the newspaper men and the other official witnesses who sat silently on the wooden benches facing the electric chair. Hamby stopped before the chair, pinched the fire from his cigarette, and spoke to the warden:

“May I say a word?”

“Certainly,” replied the warden, “anything you like.”

“Thank you,” said Hamby. He turned to the witnesses.

“I Just want to say. gentlemen, that any man who stood in front of Jay B. Allen’s gun had a chance. That’s all ”

He sat calmly in the chair and motioned to the guards.

“Go ahead, boys!”

The guards busied themselves adjusting the electrodes and the straps and the prison physician came nearer to see that everything was done properly. Hamby noticed him and smiled.

“Where is the red handkerchief, Doc?” he asked.

This referred to a joke, as he termed it, which he had been having with the physician. He had suggested that the latter obtain a new, bright red bandana handkerchief with which to signal the electrician when everything was ready for throwing the switch.

And these were the last words that Hamby ever spoke.

The doctor made an almost imperceptible motion with his hand; behind the curtain the electrician threw the switch, there was a low humming sound and Gordon Fawcett Hamby was dead with a smile on his face and a joke on his lips.

He was young, somewhere in the early twenties, but he left behind him a criminal record that has been equaled by few. Guards who had been at Sing Sing for many years and who have seen many men die say that Hamby faced the electric chair more courageously than any other man who ever passed through the little green door, with the possible exception of two—Carlyle Harris and Sam Haynes.

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement