Another tuning story had to do with his work at our university, when he had been tuning several hours and was returning his campus service requests to me. He was always cheerful, but on that particular occasion he was even more radiant. It wasn’t a new revelation, but like a child having discovered something of greatest curiosity and interest he said, “I LOVE tuning!” That was Warren’s zest for something he had done for decades, but in keeping his mind active and fresh, he constantly was employing the latest technique and was endeavoring to do it better than he had done in the past, which is the reason he was an active, loyal Piano Technicians Guild member. He bought Electronic Tuning Devices, the Verituner and then later, an Accutuner III, to compare them. He read the manuals extensively, could explain how they worked and what their special features were, and shared how they helped him (consistently positive!) . . . when he was in his 70’s and early 80’s! He was flexible. He already tuned well as an aural tuner. He would always say “I tune, but I don’t know much about the other work.” But when I had a question, he was encyclopedic in drawing diagrams and charts regarding tuning, in explaining regulation, and telling about certain idiosyncratic piano actions. The Piano Technician Guild was important for fellowship, but Warren learned much from the PTG that he put into practice. He was always grateful for the men, like Sam Smith and “Old Mr. Case” who had been provided answers and tools for him. These men helped him past the learning that he got from his Niles Bryant tuning course, that was his initiation into piano technology.

“Mr. Mack” was well-loved by his students through the generations. His students were interested in knowing his health condition, as their concern grew in his declining years, and they knew his Kendal Green Drive address and checked up on him. “Delighted” is a word overused in this tribute, but Warren was delightful, and he was delighted from his innermost being with certain things, especially if it had to do with music and young people. My young friend, from a rural setting, where fine arts are not a high priority, Warren declared to “have style,” much to my young friend’s building-up. Another student of mine, with whom I visited Warren, was “brilliant and as good as the young pianist we recently heard who placed high in the Van Cliburn competition.” Warren built up enheartened people! He never thought of himself when he could benefit another person. His students called, dropped by, and sent letters (he wouldn’t touch the computer or Margaret’s iPad . . . Alexa he enjoyed, however, with which he had much humor and it was a means of frequent calls from his family members). Students reciprocated the love that he had shared so freely. One of his students, Holly Kneads Fordham, wrote in her tribute to her beloved teacher: “He was funny and enjoyed trying to prank me from time to time. One time in particular he jumped up from behind the piano with a scary mask on. By this time, I was used to his antics, so I just replied, ‘Hi, Mr. Mack.’ He got such a kick out of that.” Warren drove to Florida to play for Heather and Mark’s wedding. She continues, relating how she and her family would get together with him from time to time years later: “Our visits were always so encouraging. I was able to tell him how much of an influence he had on my life and how loved he was. . . Praise the Lord for his life and his faithful service for so many years. I am especially grateful for all that he taught me: the wonderful piano instruction, but more importantly, his wonderful example of loving God and loving others.” Another student was partly responsible for establishing a scholarship, using Warren’s name, for the benefit of future students. That student also kept a close association with Warren for decades and said that Warren was the teacher that she needed during her college years. Because of his popularity, Warren gained friends among the students he did not teach, one of whom, with Warren totally agreeable to the hilarity, dubbed him “Moron Whack!”

Ministry in churches, with students, and as a chaplain’s assistance, was just below his love for his family, in how he felt useful and fulfilled. Pastor Peterson, who typed “like this with two fingers [animated demonstration with facial expression] . . . was a brilliant man . . . and he said, ‘Warren, if you ever have trouble with anyone just tell them to come to me!’” Carmah C. Underwood was Warren’s much-loved, career chaplain, with whom he spent a little leisure time at the end of his tour in WWII. The official assistant chaplain was A. D. Langston, and Warren said that the three of them “got along like family.” Underwood constantly carried a camera, and Warren has pictures of Underwood when (eventually) Lieutenant Colonel Underwood took Warren to view the ruins of Nuremberg, at the close of the war. Warren assisted the chaplain’s services by playing the portable pump organ and helping to conduct services. After returning to the United States, because of his outstanding musical talent and out-going personality, during his student years, Warren traveled throughout sections of the United States with evangelistic teams on three extended tours. He visited the Western states, and vividly described riding in an unairconditioned car, with wool seat covers, a group of six men, through the heat of Southern California and Arizona. Their attire also consisted of wool suits, for the services in unairconditioned buildings. But Warren made life-long friends with quality men through this close contact, and it afforded him an opportunity to see parts of the country he had never previously visited. These traveling companions always referred to Warren as “Mark,” because a pastor once confused Warren’s last name, changed a letter, and called Warren “Mark.” The mistake stuck for life! Warren left Greenville to teach in Chicago. He had caught the attention of the man in charge of the BJU ministerial students, who recommended Warren to the work in Chicago. Later Warren led music in a church in Cleveland, Ohio, and his work with Pastor Peterson followed that, in Warren, Ohio. These were fruitful ministries and people from these ministries remained friends and communicated with Warren and Margaret for the years to come. In 1963 Warren and Margaret were asked to return to their alma mater to teach. Warren taught church music administration courses, the high school choir, and piano. While in Greenville he was the music minister at Hampton Park Baptist Church, where he led the congregational singing, organized the music program, and conducted the choir.

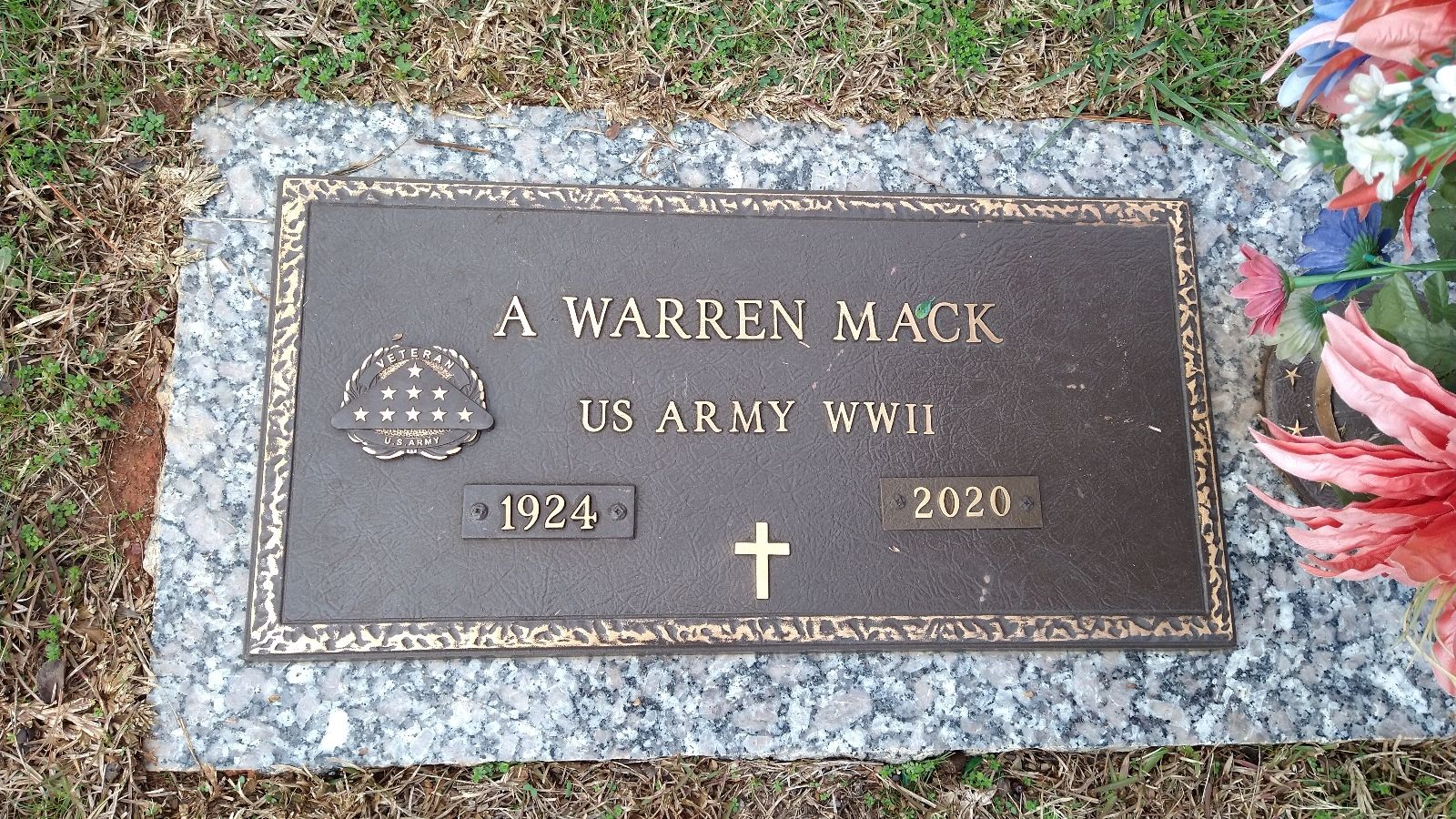

You could not know Warren Mack and not hear about WWII. WWII was always on his mind! Warren was in five campaigns: Normandy, northern France, Rhineland, Battle of Bulge, Central Europe (Czechoslovakia). He was trained as a radio operator. A memory of joining the military was having “all kinds of shots, even one for yellow fever.” He first trained in Camp Wheeler, near Macon, Georgia, and the camp was set up to train replacements for men killed in action. Warren related, “after leaving Camp Mead, we were loaded up with a gas mask, overcoat, clothes, all of which was given up about the first day at Normandy.” From those original government-issued pieces of equipment, he did keep one army blanket. He joined the First Division, which had already been at the Kasserine Pass in North Africa. At age 20 years old, in France, Belgium, Germany, and Czechoslovakia, he basically lived outdoors. The total twenty-eight months profoundly added to Warren’s character, stories, and thankfulness for life (any time he talked about the military cemeteries he’d visited in France he was deeply emotional, thinking back on the thousands, who did not return following the war).

Warren was in active duty from October 19, 1943 until January 17, 1946. He loved to tell stories and tell them in such a way as to make you feel the experience. After not-so-uplifting memories of “busyness and waiting,” that the troops experienced in the United Kingdom, Warren entered continental Europe on “D-Day plus 6,” June 12, 1944, as “cannon fodder,” in his estimation. (He always said that the average soldier had no idea what he was doing or where he was going. He even wondered if anyone knew what was happening. “You just had to follow orders.”) He, and those who entered the continent when he did, stood in for the slain men who didn’t make it past the beaches. Most of the initial invasion action was completed by that time, but fighting was heavy within just a few miles. For months the soldiers lived outside, protected at night only by their “shelter half.” They rarely enjoyed showering or clean clothes. “We all smelled the same, so we didn’t realize it.” They ate rations from tin cans and were thankful to have food. The winter weather was unusually, bitterly cold the Winter of 1944-45, and during the opening days of the Battle of the Bulge the Germans were protected by a thick cloud cover, that prevented the Allied aviators from aiding the troops. Just after the beginning of the Battle of the Bulge, when Warren and his group were quite near the Hürtgen Forest, through which the Germans’ surprise “just appeared,” he and a few others were taken by truck to a small Belgian town, Waimes, which was “without a single, living occupant, windows open, curtains fluttering in the wind, the houses evacuated quickly, with plates on the table ready for a meal.” Warren’s details were so vivid about this town that you felt you were there. In Waimes, his party with was actually behind the enemy’s battle lines during their stay, as was evidenced by the abandoned German vehicles left near the house where Warren’s group slept. Probably the Malmedy massacre, where eighty-four prisoners of war were villainously gunned down, had already occurred, but in Waimes Warren was within four kilometers of the site of that atrocity, and he arrived in the vicinity within days of that brutal, shameful, unnecessary tragedy.

Another significant WWII-related story happened, ironically, as he was being transported back to the United States. On December 14, 1945, Warren left Le Harve, France on the ship, Athos II, with 212 WACS & 2,799 servicemen. On December 21, 1945, they met a violent storm in mid-ocean. Warren could imitate sounds and described settings in a way to send shivers down your backbone. When he made sounds of artillery you felt the shock of the blast. The peril of the Atlantic storm, through which the Athos II was trying to maneuver, is another fearful experience that Warren could relate graphically. He described the glass breaking in the infirmary as the medicine bottles crashed to the floor, the vessel’s rudder’s grinding as it was lifted completely out of the water (that vibration apparently jarred the entire ship, so that everyone felt it), the kitchen was destroyed by loose appliances crashing from wall to wall, men were clutching their hammocks so that they wouldn’t be thrown to the deck, and as only Warren could say it, “battle-hardened men were calling out loud ‘God to save us,’” they were so certain that after they had dodged bullets and shrapnel, they were going to be lost at sea. The storm lasted several hours and nearly destroyed the liner-turned-troop

-ship. To quote the YouTube account, “The Final Magic Carpet Ride of the Athos II and USS Enterprise,” “On 23rd December a course was set for the Azore Islands for repairs. By evening they were navigating calm waters.” They limped to the Azores, where the veterans were not allowed to disembark. On January 6, 1946 the US aircraft carrier USS Enterprise arrived to convey them to New York, where they landed on January 17, 1946. (The next day the USS Enterprise was officially decommissioned, never to be at sea again.)

Warren was “in conflict” – it can hardly be so described – with exactly one “enemy soldier,” a mere youth, in the closing days of the war. That “soldier” was glad to be “captured” by the invading army, who would give him any medical help he needed and healthy food.

Warren specifically made the point of telling me the he was never in a train during the war in Europe. “It was dangerous to be in a train. They would strafe trains.” He traveled on a Jeep or in a two-and-a-half-ton truck.

Before the Battle of the Bulge, at the end of November or the beginning of December 1944 the Belgians, who had been liberated, volunteered to house US military personnel to give them relief from the exigencies of their outdoor life. The Schyns family in Thimister-Clermont, Belgium graciously took Warren in and provided a home atmosphere, a much-needed reprieve from outdoor living in the intemperate weather. After arriving in the United States – and surprising his parents when he returned home to Greensburg – among Warren’s war stories was the one about the gracious Schyns family. In August 1994 he and his two sons went to Belgium to thank the family for their kindness. It was a well-orchestrated reunion. The family rented a local banquet hall and honored Warren for his efforts to serve in the liberating army. Warren presented the family with an engraved plaque which quoted their sister, a nun, who had written after Warren and she were in contact with each other, "without our knowledge, a friendship can engrave and perpetuate itself in some circumstances." Again, the Schyns family felt Warren’s love and appreciation decades after they had made him feel welcome in their home. The staunchly Catholic family and the Protestants had a time of mutual appreciation, comradeship, and recollections and reflections.

Warren was elated by being included, in the company of several of his veteran friends, on an Honor Flight to visit Washington, D.C. and the war memorials. With his passing, sadly another WWII veteran no longer is living to tell his awe-inspiring stories.

Most of the people who know Warren in more recent times, met him in or after 1946, where he was associated with Bob Jones University and has had some kind of connection ever since. Funded by the GI bill, he arrived at the brand-new campus, when the school opened in Greenville, South Carolina, October, 1946. Anyone who had a long-term relationship with Warren remembers his humor. When he returned from WWII, he created monologues using military terminology and puns based on the military life that he experienced. A friend from Warren’s earliest days at BJU, took Warren to visit his own father, a WWI veteran. To me Dr. Gail Gingery enjoyed demonstrating how his father would laugh – with his eyes closed, convulsed in silent laughter – reliving his own military experiences, as Warren explain in comical terms life as a soldier. Warren remembered all manner of funny experiences of life. Every story had to do with people, from the Kentucky folks who cleaned the church and talked about “live and squirm” (with an added punch, and a twinkle in the eye . . . Warren LOVED words and loved to imitate anyone, while in total appreciation of their unique contribution to mankind!), to his friend who had been invited to a bar mitzvah, who when asked if he would like more to eat, responded, “no, I’ve had Gentile sufficient.”

An elderly, saintly missionary lady, known for her prayer life, loved hymns and taught hymnology at BJU, after her retirement. She was a tiny person, who wore a hat to all functions, because she had almost no hair. She had much personality, and her prayer-life was genuine and noteworthy. Once an unfortunate person knocked while she was opening class in prayer, and she responded, “just a minute, Lord, Satan is at the door!” (That person was none other than the founder of the University, Dr. Bob Jones, Sr., much to the amusement of the classroom of students!) Warren loved to tell the story that Jim Ryerson was leading the singing in the hymnology course one day and got a bit too close to Dr. Grace Haight and knocked her hat to the floor. Even decades later Warren laughed through this story, because he remembered his college classmates “losing it” every minute or two for the rest of the class period. They weren’t laughing at Dr. Haight. They were laughing at the occasion when their esteemed teacher had so unceremoniously lost her head covering, much to the chagrin of poor Jim and his sprawling arms.

Warren cherished the camaraderie of his well-over-six-feet-tall friend, BJU colleague and Dean of Fine Arts, Dwight Gustafson. “Gus,” placing himself directly in front of Warren, towering above Warren’s head, pretending to look out away from himself, well over Warren’s head, would ask good-naturedly, repeatedly, “where’s Warren Mack?” At Warren’s height, not far over five feet tall, well under the view of “Gus,” this was a joke that both friends reveled in, and one that Warren enjoyed telling, even recently. Warren would reply to his friend, "and look at how much of you is unnecessary." (Warren was always kind. I never realized that he was also QUITE quick! He had high intelligence along with that amiable personality!) He usually followed this story with “I have the shortest legs in captivity.” His warmth and personality ALWAYS made him monumental to me and all who knew him, regardless of his physical height.

Four of us piano technicians, Warren, Bill Maxim, Sammy Smith, and I, regularly met for breakfast at IHOP. We enjoyed a visit of comparing experiences, getting nutrition to start the workday, laughing, and sharing burdens. (My wife seems to think that piano technicians have a natural tendency to talk. I’m not sure why our wives never seemed to want to be along with us for these breakfast occasions!) Sammy and I would be amazed that Warren and Bill could say one limerick after another, from total recall. Amazing minds! The limericks were all clean, clever, and brought much laughter. It was delightful to watch those two friends regale us. It was totally wholesome, and there was no rivalry whatsoever between them. It was a time of pure pleasure and humor! What they had in their minds revealed an earlier era, which emphasized using your brain, rather than just being entertained, and involving themselves in something mind-expanding for the amusement of others. This limerick is typical of Warren’s repertoire:

A diminutive psychic named Marge

Was convicted of a most heinous charge.

But despite lock and key

Next day she broke free

And the headline read "Small medium at large."

Morally, Warren was exemplary. As he told me, going into homes “I never took so much as a paperclip.” He was honest and trustworthy. He was committed to one woman, his beloved, beautiful, talented, “completer:” Margaret Lydia Cowgill Mack (May 15, 1927- Mar 23, 2017), whom he married on August 19, 1950, near her childhood home in Glenn Dale, Prince George's County, Maryland. Several times Warren mentioned his first piano tuning customers. He never forgot their kindness and the beginning of his “second profession,” which he took up because it was piano-related and, as a teacher, he needed summer work. He retired from teaching at BJU in the late 1980’s and, for another 20 years, tuned there weekly, in addition to servicing home and church pianos. Often, he expressed his thanks to the University for their friendship and consistent employment.

Another tuning story had to do with his work at our university, when he had been tuning several hours and was returning his campus service requests to me. He was always cheerful, but on that particular occasion he was even more radiant. It wasn’t a new revelation, but like a child having discovered something of greatest curiosity and interest he said, “I LOVE tuning!” That was Warren’s zest for something he had done for decades, but in keeping his mind active and fresh, he constantly was employing the latest technique and was endeavoring to do it better than he had done in the past, which is the reason he was an active, loyal Piano Technicians Guild member. He bought Electronic Tuning Devices, the Verituner and then later, an Accutuner III, to compare them. He read the manuals extensively, could explain how they worked and what their special features were, and shared how they helped him (consistently positive!) . . . when he was in his 70’s and early 80’s! He was flexible. He already tuned well as an aural tuner. He would always say “I tune, but I don’t know much about the other work.” But when I had a question, he was encyclopedic in drawing diagrams and charts regarding tuning, in explaining regulation, and telling about certain idiosyncratic piano actions. The Piano Technician Guild was important for fellowship, but Warren learned much from the PTG that he put into practice. He was always grateful for the men, like Sam Smith and “Old Mr. Case” who had been provided answers and tools for him. These men helped him past the learning that he got from his Niles Bryant tuning course, that was his initiation into piano technology.

“Mr. Mack” was well-loved by his students through the generations. His students were interested in knowing his health condition, as their concern grew in his declining years, and they knew his Kendal Green Drive address and checked up on him. “Delighted” is a word overused in this tribute, but Warren was delightful, and he was delighted from his innermost being with certain things, especially if it had to do with music and young people. My young friend, from a rural setting, where fine arts are not a high priority, Warren declared to “have style,” much to my young friend’s building-up. Another student of mine, with whom I visited Warren, was “brilliant and as good as the young pianist we recently heard who placed high in the Van Cliburn competition.” Warren built up enheartened people! He never thought of himself when he could benefit another person. His students called, dropped by, and sent letters (he wouldn’t touch the computer or Margaret’s iPad . . . Alexa he enjoyed, however, with which he had much humor and it was a means of frequent calls from his family members). Students reciprocated the love that he had shared so freely. One of his students, Holly Kneads Fordham, wrote in her tribute to her beloved teacher: “He was funny and enjoyed trying to prank me from time to time. One time in particular he jumped up from behind the piano with a scary mask on. By this time, I was used to his antics, so I just replied, ‘Hi, Mr. Mack.’ He got such a kick out of that.” Warren drove to Florida to play for Heather and Mark’s wedding. She continues, relating how she and her family would get together with him from time to time years later: “Our visits were always so encouraging. I was able to tell him how much of an influence he had on my life and how loved he was. . . Praise the Lord for his life and his faithful service for so many years. I am especially grateful for all that he taught me: the wonderful piano instruction, but more importantly, his wonderful example of loving God and loving others.” Another student was partly responsible for establishing a scholarship, using Warren’s name, for the benefit of future students. That student also kept a close association with Warren for decades and said that Warren was the teacher that she needed during her college years. Because of his popularity, Warren gained friends among the students he did not teach, one of whom, with Warren totally agreeable to the hilarity, dubbed him “Moron Whack!”

Ministry in churches, with students, and as a chaplain’s assistance, was just below his love for his family, in how he felt useful and fulfilled. Pastor Peterson, who typed “like this with two fingers [animated demonstration with facial expression] . . . was a brilliant man . . . and he said, ‘Warren, if you ever have trouble with anyone just tell them to come to me!’” Carmah C. Underwood was Warren’s much-loved, career chaplain, with whom he spent a little leisure time at the end of his tour in WWII. The official assistant chaplain was A. D. Langston, and Warren said that the three of them “got along like family.” Underwood constantly carried a camera, and Warren has pictures of Underwood when (eventually) Lieutenant Colonel Underwood took Warren to view the ruins of Nuremberg, at the close of the war. Warren assisted the chaplain’s services by playing the portable pump organ and helping to conduct services. After returning to the United States, because of his outstanding musical talent and out-going personality, during his student years, Warren traveled throughout sections of the United States with evangelistic teams on three extended tours. He visited the Western states, and vividly described riding in an unairconditioned car, with wool seat covers, a group of six men, through the heat of Southern California and Arizona. Their attire also consisted of wool suits, for the services in unairconditioned buildings. But Warren made life-long friends with quality men through this close contact, and it afforded him an opportunity to see parts of the country he had never previously visited. These traveling companions always referred to Warren as “Mark,” because a pastor once confused Warren’s last name, changed a letter, and called Warren “Mark.” The mistake stuck for life! Warren left Greenville to teach in Chicago. He had caught the attention of the man in charge of the BJU ministerial students, who recommended Warren to the work in Chicago. Later Warren led music in a church in Cleveland, Ohio, and his work with Pastor Peterson followed that, in Warren, Ohio. These were fruitful ministries and people from these ministries remained friends and communicated with Warren and Margaret for the years to come. In 1963 Warren and Margaret were asked to return to their alma mater to teach. Warren taught church music administration courses, the high school choir, and piano. While in Greenville he was the music minister at Hampton Park Baptist Church, where he led the congregational singing, organized the music program, and conducted the choir.

You could not know Warren Mack and not hear about WWII. WWII was always on his mind! Warren was in five campaigns: Normandy, northern France, Rhineland, Battle of Bulge, Central Europe (Czechoslovakia). He was trained as a radio operator. A memory of joining the military was having “all kinds of shots, even one for yellow fever.” He first trained in Camp Wheeler, near Macon, Georgia, and the camp was set up to train replacements for men killed in action. Warren related, “after leaving Camp Mead, we were loaded up with a gas mask, overcoat, clothes, all of which was given up about the first day at Normandy.” From those original government-issued pieces of equipment, he did keep one army blanket. He joined the First Division, which had already been at the Kasserine Pass in North Africa. At age 20 years old, in France, Belgium, Germany, and Czechoslovakia, he basically lived outdoors. The total twenty-eight months profoundly added to Warren’s character, stories, and thankfulness for life (any time he talked about the military cemeteries he’d visited in France he was deeply emotional, thinking back on the thousands, who did not return following the war).

Warren was in active duty from October 19, 1943 until January 17, 1946. He loved to tell stories and tell them in such a way as to make you feel the experience. After not-so-uplifting memories of “busyness and waiting,” that the troops experienced in the United Kingdom, Warren entered continental Europe on “D-Day plus 6,” June 12, 1944, as “cannon fodder,” in his estimation. (He always said that the average soldier had no idea what he was doing or where he was going. He even wondered if anyone knew what was happening. “You just had to follow orders.”) He, and those who entered the continent when he did, stood in for the slain men who didn’t make it past the beaches. Most of the initial invasion action was completed by that time, but fighting was heavy within just a few miles. For months the soldiers lived outside, protected at night only by their “shelter half.” They rarely enjoyed showering or clean clothes. “We all smelled the same, so we didn’t realize it.” They ate rations from tin cans and were thankful to have food. The winter weather was unusually, bitterly cold the Winter of 1944-45, and during the opening days of the Battle of the Bulge the Germans were protected by a thick cloud cover, that prevented the Allied aviators from aiding the troops. Just after the beginning of the Battle of the Bulge, when Warren and his group were quite near the Hürtgen Forest, through which the Germans’ surprise “just appeared,” he and a few others were taken by truck to a small Belgian town, Waimes, which was “without a single, living occupant, windows open, curtains fluttering in the wind, the houses evacuated quickly, with plates on the table ready for a meal.” Warren’s details were so vivid about this town that you felt you were there. In Waimes, his party with was actually behind the enemy’s battle lines during their stay, as was evidenced by the abandoned German vehicles left near the house where Warren’s group slept. Probably the Malmedy massacre, where eighty-four prisoners of war were villainously gunned down, had already occurred, but in Waimes Warren was within four kilometers of the site of that atrocity, and he arrived in the vicinity within days of that brutal, shameful, unnecessary tragedy.

Another significant WWII-related story happened, ironically, as he was being transported back to the United States. On December 14, 1945, Warren left Le Harve, France on the ship, Athos II, with 212 WACS & 2,799 servicemen. On December 21, 1945, they met a violent storm in mid-ocean. Warren could imitate sounds and described settings in a way to send shivers down your backbone. When he made sounds of artillery you felt the shock of the blast. The peril of the Atlantic storm, through which the Athos II was trying to maneuver, is another fearful experience that Warren could relate graphically. He described the glass breaking in the infirmary as the medicine bottles crashed to the floor, the vessel’s rudder’s grinding as it was lifted completely out of the water (that vibration apparently jarred the entire ship, so that everyone felt it), the kitchen was destroyed by loose appliances crashing from wall to wall, men were clutching their hammocks so that they wouldn’t be thrown to the deck, and as only Warren could say it, “battle-hardened men were calling out loud ‘God to save us,’” they were so certain that after they had dodged bullets and shrapnel, they were going to be lost at sea. The storm lasted several hours and nearly destroyed the liner-turned-troop

-ship. To quote the YouTube account, “The Final Magic Carpet Ride of the Athos II and USS Enterprise,” “On 23rd December a course was set for the Azore Islands for repairs. By evening they were navigating calm waters.” They limped to the Azores, where the veterans were not allowed to disembark. On January 6, 1946 the US aircraft carrier USS Enterprise arrived to convey them to New York, where they landed on January 17, 1946. (The next day the USS Enterprise was officially decommissioned, never to be at sea again.)

Warren was “in conflict” – it can hardly be so described – with exactly one “enemy soldier,” a mere youth, in the closing days of the war. That “soldier” was glad to be “captured” by the invading army, who would give him any medical help he needed and healthy food.

Warren specifically made the point of telling me the he was never in a train during the war in Europe. “It was dangerous to be in a train. They would strafe trains.” He traveled on a Jeep or in a two-and-a-half-ton truck.

Before the Battle of the Bulge, at the end of November or the beginning of December 1944 the Belgians, who had been liberated, volunteered to house US military personnel to give them relief from the exigencies of their outdoor life. The Schyns family in Thimister-Clermont, Belgium graciously took Warren in and provided a home atmosphere, a much-needed reprieve from outdoor living in the intemperate weather. After arriving in the United States – and surprising his parents when he returned home to Greensburg – among Warren’s war stories was the one about the gracious Schyns family. In August 1994 he and his two sons went to Belgium to thank the family for their kindness. It was a well-orchestrated reunion. The family rented a local banquet hall and honored Warren for his efforts to serve in the liberating army. Warren presented the family with an engraved plaque which quoted their sister, a nun, who had written after Warren and she were in contact with each other, "without our knowledge, a friendship can engrave and perpetuate itself in some circumstances." Again, the Schyns family felt Warren’s love and appreciation decades after they had made him feel welcome in their home. The staunchly Catholic family and the Protestants had a time of mutual appreciation, comradeship, and recollections and reflections.

Warren was elated by being included, in the company of several of his veteran friends, on an Honor Flight to visit Washington, D.C. and the war memorials. With his passing, sadly another WWII veteran no longer is living to tell his awe-inspiring stories.

Most of the people who know Warren in more recent times, met him in or after 1946, where he was associated with Bob Jones University and has had some kind of connection ever since. Funded by the GI bill, he arrived at the brand-new campus, when the school opened in Greenville, South Carolina, October, 1946. Anyone who had a long-term relationship with Warren remembers his humor. When he returned from WWII, he created monologues using military terminology and puns based on the military life that he experienced. A friend from Warren’s earliest days at BJU, took Warren to visit his own father, a WWI veteran. To me Dr. Gail Gingery enjoyed demonstrating how his father would laugh – with his eyes closed, convulsed in silent laughter – reliving his own military experiences, as Warren explain in comical terms life as a soldier. Warren remembered all manner of funny experiences of life. Every story had to do with people, from the Kentucky folks who cleaned the church and talked about “live and squirm” (with an added punch, and a twinkle in the eye . . . Warren LOVED words and loved to imitate anyone, while in total appreciation of their unique contribution to mankind!), to his friend who had been invited to a bar mitzvah, who when asked if he would like more to eat, responded, “no, I’ve had Gentile sufficient.”

An elderly, saintly missionary lady, known for her prayer life, loved hymns and taught hymnology at BJU, after her retirement. She was a tiny person, who wore a hat to all functions, because she had almost no hair. She had much personality, and her prayer-life was genuine and noteworthy. Once an unfortunate person knocked while she was opening class in prayer, and she responded, “just a minute, Lord, Satan is at the door!” (That person was none other than the founder of the University, Dr. Bob Jones, Sr., much to the amusement of the classroom of students!) Warren loved to tell the story that Jim Ryerson was leading the singing in the hymnology course one day and got a bit too close to Dr. Grace Haight and knocked her hat to the floor. Even decades later Warren laughed through this story, because he remembered his college classmates “losing it” every minute or two for the rest of the class period. They weren’t laughing at Dr. Haight. They were laughing at the occasion when their esteemed teacher had so unceremoniously lost her head covering, much to the chagrin of poor Jim and his sprawling arms.

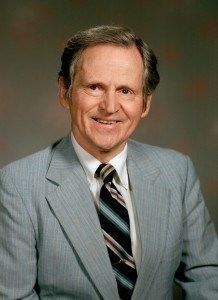

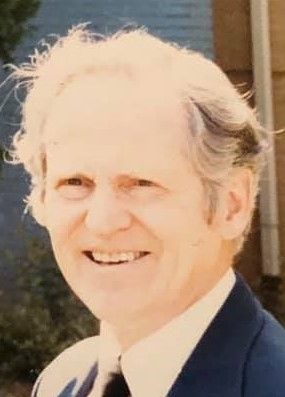

Warren cherished the camaraderie of his well-over-six-feet-tall friend, BJU colleague and Dean of Fine Arts, Dwight Gustafson. “Gus,” placing himself directly in front of Warren, towering above Warren’s head, pretending to look out away from himself, well over Warren’s head, would ask good-naturedly, repeatedly, “where’s Warren Mack?” At Warren’s height, not far over five feet tall, well under the view of “Gus,” this was a joke that both friends reveled in, and one that Warren enjoyed telling, even recently. Warren would reply to his friend, "and look at how much of you is unnecessary." (Warren was always kind. I never realized that he was also QUITE quick! He had high intelligence along with that amiable personality!) He usually followed this story with “I have the shortest legs in captivity.” His warmth and personality ALWAYS made him monumental to me and all who knew him, regardless of his physical height.

Four of us piano technicians, Warren, Bill Maxim, Sammy Smith, and I, regularly met for breakfast at IHOP. We enjoyed a visit of comparing experiences, getting nutrition to start the workday, laughing, and sharing burdens. (My wife seems to think that piano technicians have a natural tendency to talk. I’m not sure why our wives never seemed to want to be along with us for these breakfast occasions!) Sammy and I would be amazed that Warren and Bill could say one limerick after another, from total recall. Amazing minds! The limericks were all clean, clever, and brought much laughter. It was delightful to watch those two friends regale us. It was totally wholesome, and there was no rivalry whatsoever between them. It was a time of pure pleasure and humor! What they had in their minds revealed an earlier era, which emphasized using your brain, rather than just being entertained, and involving themselves in something mind-expanding for the amusement of others. This limerick is typical of Warren’s repertoire:

A diminutive psychic named Marge

Was convicted of a most heinous charge.

But despite lock and key

Next day she broke free

And the headline read "Small medium at large."

Morally, Warren was exemplary. As he told me, going into homes “I never took so much as a paperclip.” He was honest and trustworthy. He was committed to one woman, his beloved, beautiful, talented, “completer:” Margaret Lydia Cowgill Mack (May 15, 1927- Mar 23, 2017), whom he married on August 19, 1950, near her childhood home in Glenn Dale, Prince George's County, Maryland. Several times Warren mentioned his first piano tuning customers. He never forgot their kindness and the beginning of his “second profession,” which he took up because it was piano-related and, as a teacher, he needed summer work. He retired from teaching at BJU in the late 1980’s and, for another 20 years, tuned there weekly, in addition to servicing home and church pianos. Often, he expressed his thanks to the University for their friendship and consistent employment.

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement