Hugh was the son of Elkanah L. and Eleanor Elizabeth Lee Black. He was the husband of Rosa Bell Hall Black. They had seven children.

Below are some of my memories of my grandfather.

PAPA BLACK

When I was four Papa taught me the letters of the alphabet, how to read, and the numbers from one to one hundred. I learned how to count in my head by playing his favorite game, dominoes.

Papa was always up by 5:00 A.M. He took me with him to milk the cows, feed the chickens, and pick up the eggs. Mama had breakfast ready by the time we had finished our chores. We usually ate grits , eggs, sausage, and homemade biscuits, but sometimes we ate just biscuits with syrup and butter, and sometimes just oatmeal. He always reminded me to eat everything on my plate.

After breakfast, Papa usually went outside to hoe in his garden or tend to his watermelon patch. I usually went with him. He got so mad when he found that my older brothers on the afternoon before had cut several watermelons, eaten just the heart, and left the rest.

Papa let me help him plant his garden and showed me how to plow. I loved the smell of the soil and the neat, straight rows. He grew white and speckled butterbeans, squash, Irish potatoes, turnip and collard greens, peas, okra, vegetable eggs (eggplants), hot and mild peppers, cucumbers, yellow corn, watermelons, and lots of fruits on trees. I helped him pick beans and peas and pull corn when they were ready. Then came the shelling and shucking. I remember sore thumbnails from shelling beans and peas and the marvel of corn husks and corn silk. I was amazed at how God wrapped His varieties of vegetables and fruits. Papa taught me to peel an apple all the way around in one long strip without dropping any of the peel. He fed me red apples, crab apples, figs, peaches, pears, grapes, persimmons, and scuppernongs he had planted himself, and we spent hours picking up his pecans. When we weren't gardening or working (It wasn't work to me, but fun), we went on long walks in the woods . He tried to teach me the names of all the trees and birds. I wish I had listened better.

When Papa raked the yard, I wanted to help, so he made me a small rake of my own. When we got hot and thirsty, he drew up some cold well water, which I drank from an old tin dipper, and he drank from a gourd dipper he had made.

If Mama wanted to have chicken for lunch (she called it dinner), Papa would go out to the crib yard, grab a chicken, and wring its neck. I hated that! I had become attached to each one on our morning feedings. If Mama wanted a hen, Papa would chop its head off with an axe. He told me a hen's neck was too thick and tough to wring. I vividly remember how horrified I was when the headless hen with blood still dripping would flop around or run straight at me right after Papa chopped off her head. He took the whole thing matter-of-factly and unemotionally, and Mama

cleaned the hen and cooked it.

After lunch was the highlight of Papa's day. That was when the mailman came, bringing him the mail and his favorite newspapers, the Montgomery Advertiser and the Butler County News. He read every article, many out loud to me . His other favorite reading material was the Farmers Almanac, in which he studied moon phases, found out when light and dark nights would be, and planned the best times to plant his crops.

Some hot, sunny afternoons Papa and I would walk two miles to visit his sister, my great-aunt Bethena and Uncle John A. [Morrow]. They lived down a dusty, dirt road and we arrived all hot and dry-mouthed. One time Papa let me have one taste of the icy-cold beer Uncle John A. sometimes (rarely) had for company.

On every Friday the rolling store came by Papa's house. He bought me and all the other children whatever treat we wanted. Papa always had grandchildren or neighbors' children at his house. I remember one day when all of us kids-- me, Keith, Karen, Larry, Bobby Ray, and the McInvale kids-- went out to the field to play. Papa dressed up in a sheet, ran out from behind some trees and scared us to death. We ran home as fast as we could, but he was already there, not even breathing hard, when we arrived out of breath. He swore he had not been to the field at all, but just laughed and laughed.

Papa always wore a short-sleeved khaki shirt and overalls in the summer and a long-sleeved flannel shirt and overalls in the winter. He wore both with an old felt brimmed hat, except when he went to town. Then he wore his good clothes and his nice straw hat.

Every Saturday Papa and I hitched a ride the three miles to town. He always took me to the Pink Store and bought me three scoops of ice cream--one vanilla, one chocolate, and one strawberry. We spent the afternoon walking around town talking to people he knew, and he introduced himself to the few he didn't know. One Saturday in town Papa introduced me to a big, tall man named Big Jim Folsom, but I was too young to know what governor meant. Big Jim handed me a bucket, took my hand, and we walked around and took up money for his campaign.

Papa had a good memory and served as historian for the community. Anytime anybody needed to know a date of a wedding or funeral or a local or national event, they asked Papa. Just about everybody in Butler County knew him affectionately as Uncle Hugh. If anyone called him Mr. Black, he joked, "No, I'm Mr. White, but you can call me Uncle Hugh."

Papa loved to play with people's names and called only a few people by their given names. He had nicknames for my brothers, sisters, and me. Michael was Mickey, Brenda was Cooter, Paulette was Scrap, Joann was Jensie, I was Polly Ann, Larry was Pete, and Bobby was Jake. My oldest brother was an exception. Papa called him by his real name, which was Cebron. Everyone else called him Ranny, a nickname he got from Aunt Una, short for his middle name Randolph. Ranny hated to be called Cebron, and most of his friends did not know that was his name. According to my older sister, it was Papa who ended that secret.

One day when Ranny was in the tenth grade, in his first year in city school, he forgot his P.E. shoes. Papa couldn't stand for him to get a bad grade in P.E., so he caught a ride to town, went into the cafeteria where the classes were having a lunch break, and shouted in a loud voice, "Is Cebron here? He forgot his shoes!" A very embarrassed Cebron was present and had no choice but to go get his shoes. Of course all his friends never let him live down his name, but that didn't matter to Papa. He had done his duty.

Papa lived in a big white house on a hill out Highway 106 about three miles from town. The house was divided into two sides by a big hall running down the center, connecting the front porch to the back porch. For almost fifty years the hall was left open, without doors on either end. In the late fifties, Papa finally added two large, heavy oak doors to close in the hallway. The front porch contained a swing at one end and several rocking chairs. Attached to the back porch was a deep well, convenient to the near-by kitchen. Since there was no indoor plumbing, in the summer we took baths in a washtub on the back porch in cold water from the well, and in the winter we heated water on the wood stove and bathed in the kitchen.

The rooms were large with high ceilings and hardwood floors. A large fireplace on each side of the house kept the two largest rooms warm, and the wood stove warmed the kitchen. The beds were large iron ones with feather mattresses and pillows. A large chifforobe (wardrobe) in the hall held clothes. Laundry was done by hand using scrub boards, or later by a wringer type washing machine and then hung outside on the clothesline to dry. Sometimes in the winter the clothes would freeze on the line. The kitchen table was big enough for a large family. The ice man had to come every few days to bring ice for the ice box. The bathroom, of course, was an outhouse and at night a chamber pot sufficed.

Papa's room was my favorite. On the walls were pictures of him and Mama after their wedding, and one of his brother Bill who had died in a sawmill accident. The picture frames were old, gold, and very ornamental. At the foot of Papa's bed was an old railroad trunk, full of railroad mementos. Papa worked for the L&N Railroad for many years. Sometimes he let me look through the stuff in his trunk. He showed me a big rolled-up L&N calendar he had saved from the year I was born. He had one for each year a grandchild was born. He had some old railroad pocket watches in there and some nice fobs he wore when he dressed up in his suit. He had a big jar of old coins, which we later hid in the corn crib. He told me I could have the coins when he died. He did not much believe in banks because of the Stock Market Crash.

Papa loved to sit on his front porch late in the afternoon and wave to people who drove by. He always cussed a blue streak if they did not wave back. In the evenings he watched every sunset and smoked his pipe there. Sometimes at night, he sang hymns while we rocked on the porch and looked for falling stars. His favorite hymn was "Amazing Grace," and his bass voice was beautiful in the night air. Papa loved to sing and never missed a sacred harp singing.

Papa sent me to singing school, where we learned do-re-me-fa-so-la-te-do singing, the shapes of notes, and rhythm. He enjoyed gathering up his grandkids and going to the circus. He loved to go possum hunting or bird thrashing at night. Nearly every night, he listened to Amos and Andy on the radio. The only thing Papa liked more than singing was dancing. He won first prize, $15, in a buck dancing contest when he was seventy-six years old.

Papa was born on July 3 [1883], so every Fourth of July he threw a big party to celebrate. His seven children and their children, his brothers and sisters and their families, cousins, neighbors, and people from miles around all came, bringing plenty of fried chicken, dumplings, pot pies, cornbread dressing, potato salad, every possible vegetable, and all the trimmings. Tables were set up outdoors and filled with food supplied by the guests and Mama. For dessert, there were all kinds of pies and cakes, and Papa always ordered giant five-gallon barrels of ice cream--vanilla, chocolate, strawberry, and black walnut--kept cold by hot ice. He always cut plenty of watermelons. too. He filled washtubs full of ice, beer, and grape, orange crush, cokes, and RC colas. The men played dominoes, smoked, and talked. The women gossiped while cleaning up the mess. The children played all afternoon. Everyone ate too much .

Papa was famous in the community for selling a medicine called Duckworth. It was some kind of mineral water named after Preacher Duckworth, who sold it to Papa. He always kept four or five bottles on hand. It was good for all ailments, but it tasted like a green persimmon. One of Papa's favorite pranks was getting people to taste it. According to him, it was a miracle cure, and he sold it for only one dollar a bottle. Many people bought a bottle to get away from Papa's sales talk, which always included a free taste.

Mama always used to get mad at Papa about his bad habit--cursing. He cursed whether he was mad or not. He cursed in front of everyone, even Preacher Byrd. When Preacher Byrd asked him why he cursed , he said, "Its all the liars, thieves, drunkards, and sorry, lazy bums in this world. That's enough to make even a preacher cuss."

Papa was full of fun and laughter and kept us all laughing. He had a soft heart under thick skin. He was generous with hugs and love for those who loved him. When he hugged me he smelled like sweat combined with Old Spice cologne and pipe and cigar smoke. He always gave me the cigar rings off his cigars, which I proudly wore. If I had just one of those today, it would be my greatest treasure.

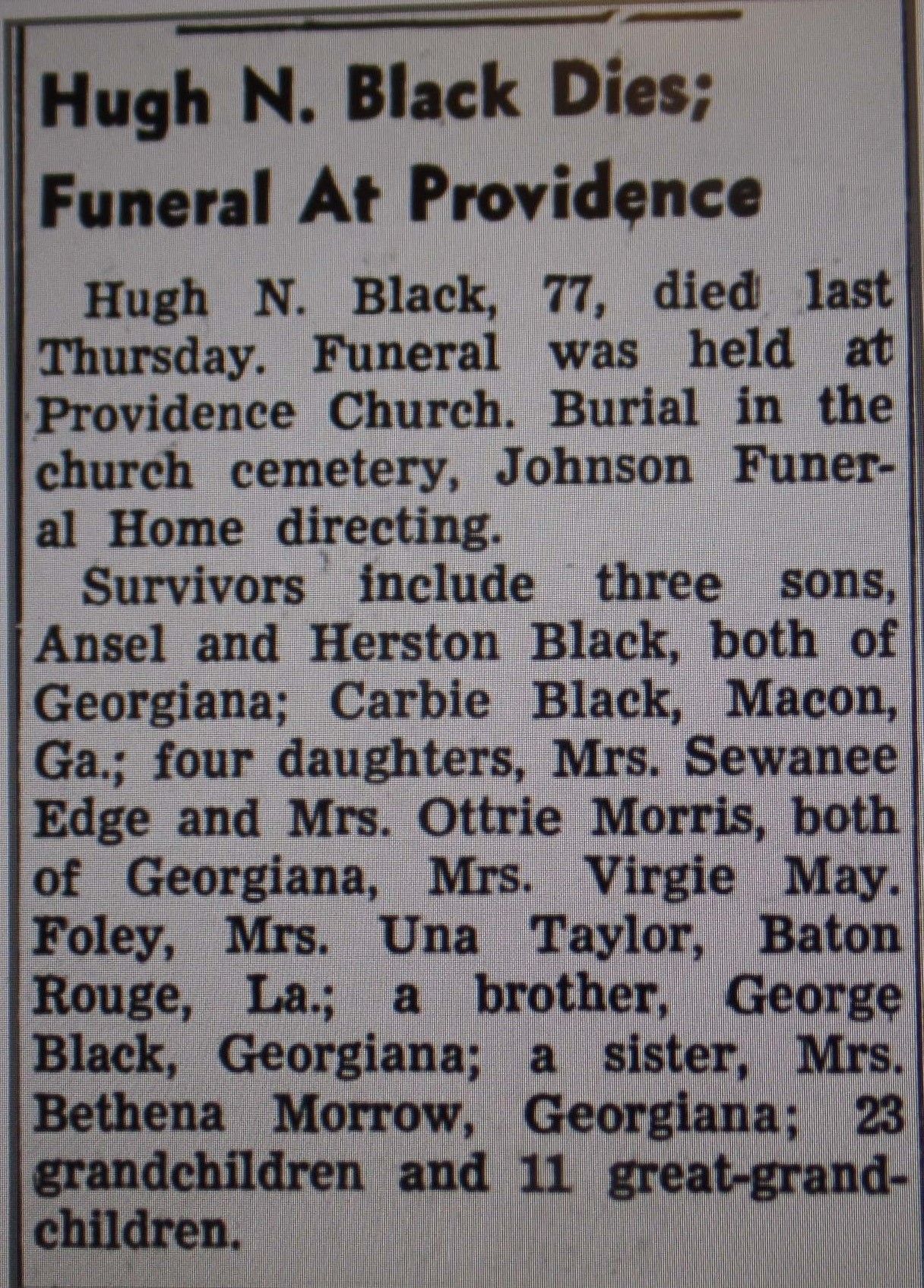

Papa died at the breakfast table of a heart attack at age seventy-seven. He had just put butter, milk, and sugar in his morning oatmeal. My mother had cooked it for him, and she was washing the dishes. She asked him something, but he did not answer. When she turned around, he was sitting there, but he was gone. I still miss him today, and I know his other living family miss him, too. [By Polly Ann (Cheryll M. Sumner)]

Hugh was the son of Elkanah L. and Eleanor Elizabeth Lee Black. He was the husband of Rosa Bell Hall Black. They had seven children.

Below are some of my memories of my grandfather.

PAPA BLACK

When I was four Papa taught me the letters of the alphabet, how to read, and the numbers from one to one hundred. I learned how to count in my head by playing his favorite game, dominoes.

Papa was always up by 5:00 A.M. He took me with him to milk the cows, feed the chickens, and pick up the eggs. Mama had breakfast ready by the time we had finished our chores. We usually ate grits , eggs, sausage, and homemade biscuits, but sometimes we ate just biscuits with syrup and butter, and sometimes just oatmeal. He always reminded me to eat everything on my plate.

After breakfast, Papa usually went outside to hoe in his garden or tend to his watermelon patch. I usually went with him. He got so mad when he found that my older brothers on the afternoon before had cut several watermelons, eaten just the heart, and left the rest.

Papa let me help him plant his garden and showed me how to plow. I loved the smell of the soil and the neat, straight rows. He grew white and speckled butterbeans, squash, Irish potatoes, turnip and collard greens, peas, okra, vegetable eggs (eggplants), hot and mild peppers, cucumbers, yellow corn, watermelons, and lots of fruits on trees. I helped him pick beans and peas and pull corn when they were ready. Then came the shelling and shucking. I remember sore thumbnails from shelling beans and peas and the marvel of corn husks and corn silk. I was amazed at how God wrapped His varieties of vegetables and fruits. Papa taught me to peel an apple all the way around in one long strip without dropping any of the peel. He fed me red apples, crab apples, figs, peaches, pears, grapes, persimmons, and scuppernongs he had planted himself, and we spent hours picking up his pecans. When we weren't gardening or working (It wasn't work to me, but fun), we went on long walks in the woods . He tried to teach me the names of all the trees and birds. I wish I had listened better.

When Papa raked the yard, I wanted to help, so he made me a small rake of my own. When we got hot and thirsty, he drew up some cold well water, which I drank from an old tin dipper, and he drank from a gourd dipper he had made.

If Mama wanted to have chicken for lunch (she called it dinner), Papa would go out to the crib yard, grab a chicken, and wring its neck. I hated that! I had become attached to each one on our morning feedings. If Mama wanted a hen, Papa would chop its head off with an axe. He told me a hen's neck was too thick and tough to wring. I vividly remember how horrified I was when the headless hen with blood still dripping would flop around or run straight at me right after Papa chopped off her head. He took the whole thing matter-of-factly and unemotionally, and Mama

cleaned the hen and cooked it.

After lunch was the highlight of Papa's day. That was when the mailman came, bringing him the mail and his favorite newspapers, the Montgomery Advertiser and the Butler County News. He read every article, many out loud to me . His other favorite reading material was the Farmers Almanac, in which he studied moon phases, found out when light and dark nights would be, and planned the best times to plant his crops.

Some hot, sunny afternoons Papa and I would walk two miles to visit his sister, my great-aunt Bethena and Uncle John A. [Morrow]. They lived down a dusty, dirt road and we arrived all hot and dry-mouthed. One time Papa let me have one taste of the icy-cold beer Uncle John A. sometimes (rarely) had for company.

On every Friday the rolling store came by Papa's house. He bought me and all the other children whatever treat we wanted. Papa always had grandchildren or neighbors' children at his house. I remember one day when all of us kids-- me, Keith, Karen, Larry, Bobby Ray, and the McInvale kids-- went out to the field to play. Papa dressed up in a sheet, ran out from behind some trees and scared us to death. We ran home as fast as we could, but he was already there, not even breathing hard, when we arrived out of breath. He swore he had not been to the field at all, but just laughed and laughed.

Papa always wore a short-sleeved khaki shirt and overalls in the summer and a long-sleeved flannel shirt and overalls in the winter. He wore both with an old felt brimmed hat, except when he went to town. Then he wore his good clothes and his nice straw hat.

Every Saturday Papa and I hitched a ride the three miles to town. He always took me to the Pink Store and bought me three scoops of ice cream--one vanilla, one chocolate, and one strawberry. We spent the afternoon walking around town talking to people he knew, and he introduced himself to the few he didn't know. One Saturday in town Papa introduced me to a big, tall man named Big Jim Folsom, but I was too young to know what governor meant. Big Jim handed me a bucket, took my hand, and we walked around and took up money for his campaign.

Papa had a good memory and served as historian for the community. Anytime anybody needed to know a date of a wedding or funeral or a local or national event, they asked Papa. Just about everybody in Butler County knew him affectionately as Uncle Hugh. If anyone called him Mr. Black, he joked, "No, I'm Mr. White, but you can call me Uncle Hugh."

Papa loved to play with people's names and called only a few people by their given names. He had nicknames for my brothers, sisters, and me. Michael was Mickey, Brenda was Cooter, Paulette was Scrap, Joann was Jensie, I was Polly Ann, Larry was Pete, and Bobby was Jake. My oldest brother was an exception. Papa called him by his real name, which was Cebron. Everyone else called him Ranny, a nickname he got from Aunt Una, short for his middle name Randolph. Ranny hated to be called Cebron, and most of his friends did not know that was his name. According to my older sister, it was Papa who ended that secret.

One day when Ranny was in the tenth grade, in his first year in city school, he forgot his P.E. shoes. Papa couldn't stand for him to get a bad grade in P.E., so he caught a ride to town, went into the cafeteria where the classes were having a lunch break, and shouted in a loud voice, "Is Cebron here? He forgot his shoes!" A very embarrassed Cebron was present and had no choice but to go get his shoes. Of course all his friends never let him live down his name, but that didn't matter to Papa. He had done his duty.

Papa lived in a big white house on a hill out Highway 106 about three miles from town. The house was divided into two sides by a big hall running down the center, connecting the front porch to the back porch. For almost fifty years the hall was left open, without doors on either end. In the late fifties, Papa finally added two large, heavy oak doors to close in the hallway. The front porch contained a swing at one end and several rocking chairs. Attached to the back porch was a deep well, convenient to the near-by kitchen. Since there was no indoor plumbing, in the summer we took baths in a washtub on the back porch in cold water from the well, and in the winter we heated water on the wood stove and bathed in the kitchen.

The rooms were large with high ceilings and hardwood floors. A large fireplace on each side of the house kept the two largest rooms warm, and the wood stove warmed the kitchen. The beds were large iron ones with feather mattresses and pillows. A large chifforobe (wardrobe) in the hall held clothes. Laundry was done by hand using scrub boards, or later by a wringer type washing machine and then hung outside on the clothesline to dry. Sometimes in the winter the clothes would freeze on the line. The kitchen table was big enough for a large family. The ice man had to come every few days to bring ice for the ice box. The bathroom, of course, was an outhouse and at night a chamber pot sufficed.

Papa's room was my favorite. On the walls were pictures of him and Mama after their wedding, and one of his brother Bill who had died in a sawmill accident. The picture frames were old, gold, and very ornamental. At the foot of Papa's bed was an old railroad trunk, full of railroad mementos. Papa worked for the L&N Railroad for many years. Sometimes he let me look through the stuff in his trunk. He showed me a big rolled-up L&N calendar he had saved from the year I was born. He had one for each year a grandchild was born. He had some old railroad pocket watches in there and some nice fobs he wore when he dressed up in his suit. He had a big jar of old coins, which we later hid in the corn crib. He told me I could have the coins when he died. He did not much believe in banks because of the Stock Market Crash.

Papa loved to sit on his front porch late in the afternoon and wave to people who drove by. He always cussed a blue streak if they did not wave back. In the evenings he watched every sunset and smoked his pipe there. Sometimes at night, he sang hymns while we rocked on the porch and looked for falling stars. His favorite hymn was "Amazing Grace," and his bass voice was beautiful in the night air. Papa loved to sing and never missed a sacred harp singing.

Papa sent me to singing school, where we learned do-re-me-fa-so-la-te-do singing, the shapes of notes, and rhythm. He enjoyed gathering up his grandkids and going to the circus. He loved to go possum hunting or bird thrashing at night. Nearly every night, he listened to Amos and Andy on the radio. The only thing Papa liked more than singing was dancing. He won first prize, $15, in a buck dancing contest when he was seventy-six years old.

Papa was born on July 3 [1883], so every Fourth of July he threw a big party to celebrate. His seven children and their children, his brothers and sisters and their families, cousins, neighbors, and people from miles around all came, bringing plenty of fried chicken, dumplings, pot pies, cornbread dressing, potato salad, every possible vegetable, and all the trimmings. Tables were set up outdoors and filled with food supplied by the guests and Mama. For dessert, there were all kinds of pies and cakes, and Papa always ordered giant five-gallon barrels of ice cream--vanilla, chocolate, strawberry, and black walnut--kept cold by hot ice. He always cut plenty of watermelons. too. He filled washtubs full of ice, beer, and grape, orange crush, cokes, and RC colas. The men played dominoes, smoked, and talked. The women gossiped while cleaning up the mess. The children played all afternoon. Everyone ate too much .

Papa was famous in the community for selling a medicine called Duckworth. It was some kind of mineral water named after Preacher Duckworth, who sold it to Papa. He always kept four or five bottles on hand. It was good for all ailments, but it tasted like a green persimmon. One of Papa's favorite pranks was getting people to taste it. According to him, it was a miracle cure, and he sold it for only one dollar a bottle. Many people bought a bottle to get away from Papa's sales talk, which always included a free taste.

Mama always used to get mad at Papa about his bad habit--cursing. He cursed whether he was mad or not. He cursed in front of everyone, even Preacher Byrd. When Preacher Byrd asked him why he cursed , he said, "Its all the liars, thieves, drunkards, and sorry, lazy bums in this world. That's enough to make even a preacher cuss."

Papa was full of fun and laughter and kept us all laughing. He had a soft heart under thick skin. He was generous with hugs and love for those who loved him. When he hugged me he smelled like sweat combined with Old Spice cologne and pipe and cigar smoke. He always gave me the cigar rings off his cigars, which I proudly wore. If I had just one of those today, it would be my greatest treasure.

Papa died at the breakfast table of a heart attack at age seventy-seven. He had just put butter, milk, and sugar in his morning oatmeal. My mother had cooked it for him, and she was washing the dishes. She asked him something, but he did not answer. When she turned around, he was sitting there, but he was gone. I still miss him today, and I know his other living family miss him, too. [By Polly Ann (Cheryll M. Sumner)]

Inscription

HUGH N. BLACK

JULY 3, 1883

MAR. 23, 1961

Family Members

-

![]()

James Edward "Jim" Black

1868–1952

-

![]()

Maryann Delilah "Did" Black Blackburn

1870–1918

-

![]()

Sarah Susan Victoria "Vick" Black Hollaway

1873–1941

-

![]()

George Robert Black

1875–1964

-

![]()

Alonzo Bennett "Lon/Ben" Black

1877–1952

-

![]()

Emily Arvilla Black English

1879–1934

-

![]()

Eleanor Bethena Black Morrow

1881–1970

-

![]()

William Thomas Black

1885–1906

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement