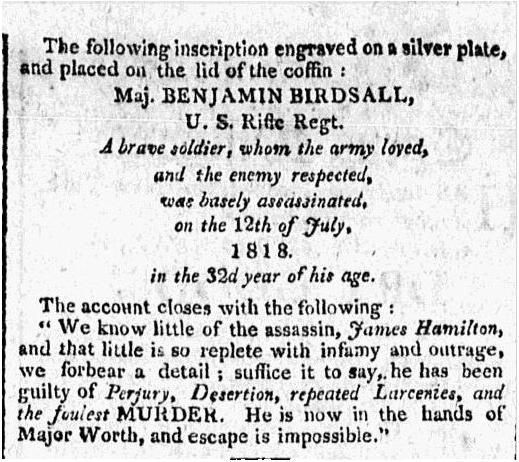

It is with feelings of deep regret, that we have to announce the death of Maj. BENJAMIN BIRDSALL, of the U.S. rifle corps, by an act of deliberate barbarity that has few parallels in our time. He was shot through the body on Sunday evening, by a private of his corps, named James Hamilton, an Irishman by birth, and breathed his last between nine and ten the same evening. His remains were interred yesterday, with military honors, amidst the deep lamentations of his relatives, the regrets of his fellow soldiers and of all who enjoyed his acquaintance. Hamilton had vowed to perpetrate this horrid act in consequence of some supposed injury he had received from the deceased. On Sunday evening, while the major was conversing with a citizen on the parade, he advanced to within a few yards of him, deliberately leveled his piece, and fulfilled his hellish design. The ball entered the right breast below the ribs, passed through the lower part of the fringe, which before death protruded from the wound, and lodged in the opposite side of the chest. Maj. B. retained his senses perfectly, conversed with the Rev. Mr. Cummins, who offered up prayers to the Fountain of Mercy in his behalf; was sensible that his wound was mortal; gave his sword and watch to his little son and took an affectionate leave of his family and friends.

Hamilton was secured and lodged, in goal, where, instead of penitence and tears, we are told he exults in having executed his diabolical purpose, with a fiend like hardihood.

Those who are acquainted with the history of the late war, need not be told of the valor and services of Maj. BIRDSALL in the northern campaigns. His merit and his sufferings procured for him the commendation and reward of his government; while he endeared himself to a numerous circle of acquaintance by his social as well as military virtues.

Maj. BIRDSALL had languished under the wounds he received in defending his country, till within a few weeks of his melancholy exit. He has left a wife and four children to deplore the loss of his support and affection.

......The remains of the brave and lamented Major Birdsall, were interred at Albany, with military honors.

Note....may be buried in Greenbush

East Greenbush was part of the Manor of Rensselaerswyck, and Albany County prior to Rensselaer County's creation in 1791. The town of Clinton was established on February 23, 1855 from the town of Greenbush at the same time as the town of North Greenbush. Three years later on April 14, 1858 the name was changed to East Greenbush by New York State Laws of 1858, Chapter 194. The town originally included land that is now the industrial and residential southend of the city of Rensselaer including Fort Crailo, this was annexed to Rensselaer in 1902.

**********

LIFE OF THURLOW WEED INCLUDING HIS AUTOBIOGRAPHY AND A MEMOIR EMBELLISHED WITH PORTRAITS AND OTHER ILLUSTRATIONS COMPLETE IN TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I.

Soon after my arrival in Albany two events occurred which attracted general interest. On the 4th of July, the remains of General Montgomery, on their way from Quebec to New York, passed through the city. The procession, consisting of the military, civic societies, and citizens of Albany, Troy, and Schenectady, was imposing, impressive, and solemn. The Grand Marshal of the day was Major Benjamin Birdsall of the United States army, who had served gallantly in the war of 1812, and who appeared on that day for the first time without the dressing upon a severe wound in the face that he received in the sortie at Fort Erie, in 1814. On the 12th of the same month, as he was, on a Sunday afternoon, about to review his rifle battalion, he was shot by one of his soldiers. He had passed two hours of that afternoon in our office chatting with two or three friends. After he left the office, I went with a friend for a walk, and returning near sundown, between the patroons and the old arsenal, I heard a rifle shot, and saw a commotion in the cantonment which lay between North Pearl Street and what is now known as the Little Basin. I ran to the spot, and assisted in removing the major (who was my intimate friend) on a litter to his residence in North Pearl Street, where he soon expired.

The excitement against the soldier was so intense that it was difficult to prevent the populace from lynching him. He was committed to the jail, but the feeling ran so high that the civil authorities requested the officer in command at the Greenbush cantonment to receive and protect the prisoner.

Major Birdsall at the commencement of the war resided on a farm which he rented from the patroon, near the Shaker village. He went with a volunteer rifle company, of which he was an officer, to Plattsburgh, where, in the battle that ensued, his gallantry attracted the attention of General Macomb, on whose recommendation, along with that of Governor Tompkins, he was appointed an officer in the United States Rifle Corps, and served subsequently on the Niagara frontier, again distinguishing himself in several battles, until, at the close of the campaign of 1814, he received his desperate wound in leading, under General Peter B. Porter, the assault upon Fort Erie. He had risen, against adverse circumstances, by intelligence and energy, to position and fame, and was justly appreciated by Albanians.

The prisoner, Hamilton, was soon indicted, arraigned, tried, convicted, and sentenced to be hanged. The trial (which I reported for the “Register”) was in the Assembly Chamber, and although Hamilton himself always admitted the charge, and manifested no solicitude for the result of the trial, somebody (his father, it was supposed) employed counsel for him, who strenuously urged an acquittal on the ground of temporary insanity occasioned by liquor, but of course producing no effect.

After his conviction, at the request of Sheriff Hempsted, I went to Hamilton s cell, with a strong feeling of repugnance, which, however, after two or three visits, was, by a revelation of all the circumstances, changed to a sorrowful sympathy. Hamilton was the natural son of a man engaged successfully in a business that ultimately made him wealthy in the city of New York. His mother, turned adrift in disgrace and destitution, struggled as well as she could for a few years, and then left him to the world’s charity.

At the commencement of the war of 1812, then about twenty years old, he enlisted, and it was shown on his trial that he served faithfully and gallantly, receiving at the close of the war an honorable discharge. He had known and greatly admired Major Birdsall during the war. After a year or two of irregularities, with uncertain and precarious employment, he sought Major Birdsall’s recruiting rendezvous and reenlisted. For more than a week before the fatal rifle was fired Hamilton had been intoxicated. On Saturday, a light-colored mulatto, a fine, soldierly-looking young man, who had served during the war, also reenlisted, and was sent to camp to be mustered in; after which, the major intended to take him to his house as a waiter. At mid-day on Sunday Hamilton was told that a negro had been recruited, and as he was, like Hamilton, a tall fellow, was to be put into his platoon and mess. This, maddened as he already was with a mixture of bad whiskey and sour cider, exasperated him beyond control. He loaded his rifle, and went prowling about in search of the “negro,” who, informed of Hamilton’s threats, kept out of his way, until at six o clock Hamilton, with rifle in hand, saw him dodge behind a tent, and started after him. At this moment the major, who was approaching, called, “Hamilton, take your place!” and the rifle, which was ready to be discharged at the soldier, was instantaneously aimed and fatally discharged at the major. In his sober senses, he would have defended Major Birdsall at the risk of his own life.

As a coincidence entitled to be remembered, it is proper to say that Major Birdsall, like the man who assassinated him, was an illegitimate child, unacknowledged until after he had distinguished himself in the war. His father, Colonel Benjamin Birdsall, an officer in the revolutionary army, and an influential citizen of Columbia County, then sent for the major and acknowledged him as a son.

After Hamilton was convicted and sentenced to execution, he requested me to write his “Life and Confession.” He told me that he was the natural son of a wealthy New Yorker, from whom he had received nothing, and whom he never saw; but although he owed him neither affection nor duty, he did not want his father s name made public. The day before his execution he asked permission of the sheriff to walk to the gallows instead of riding, as was usual, on a cart with his coffin. His request was granted. He then asked me to walk near him and witness his execution, that I might see and say that he died like a soldier. It was more than a mile from the jail to the place of execution. The sheriff s posse was escorted by a military company. I walked with the sheriff directly behind Hamilton, whose bearing was that of a soldier, proud of the attention he attracted. He ascended to the scaffold with a firm step, talked cheerfully with the clergyman for a few minutes, said good bye to the multitude, and told the sheriff he was ready. At the fatal moment, when the drop fell, the rope parted, and, to the horror of all present, Hamilton lay stretched upon the ground. But instantly springing to his feet, he stood erect until the sheriff approached him and said, “This is hard, Hamilton.” “Yes,” he replied, “but it is my own fault; I asked you for too much slack.” The sheriff then took a cart-rope, and, handing it to Hamilton, inquired, “Do you think this strong enough? “ Hamilton replied, with a smile, “It is large enough to be strong.” It was then adjusted to his neck, when he reascended, and placed himself upon the drop with a firm foot.

Again the fatal cord was cut, and in a few seconds all was over. That was the first and last execution I ever attended.

It is with feelings of deep regret, that we have to announce the death of Maj. BENJAMIN BIRDSALL, of the U.S. rifle corps, by an act of deliberate barbarity that has few parallels in our time. He was shot through the body on Sunday evening, by a private of his corps, named James Hamilton, an Irishman by birth, and breathed his last between nine and ten the same evening. His remains were interred yesterday, with military honors, amidst the deep lamentations of his relatives, the regrets of his fellow soldiers and of all who enjoyed his acquaintance. Hamilton had vowed to perpetrate this horrid act in consequence of some supposed injury he had received from the deceased. On Sunday evening, while the major was conversing with a citizen on the parade, he advanced to within a few yards of him, deliberately leveled his piece, and fulfilled his hellish design. The ball entered the right breast below the ribs, passed through the lower part of the fringe, which before death protruded from the wound, and lodged in the opposite side of the chest. Maj. B. retained his senses perfectly, conversed with the Rev. Mr. Cummins, who offered up prayers to the Fountain of Mercy in his behalf; was sensible that his wound was mortal; gave his sword and watch to his little son and took an affectionate leave of his family and friends.

Hamilton was secured and lodged, in goal, where, instead of penitence and tears, we are told he exults in having executed his diabolical purpose, with a fiend like hardihood.

Those who are acquainted with the history of the late war, need not be told of the valor and services of Maj. BIRDSALL in the northern campaigns. His merit and his sufferings procured for him the commendation and reward of his government; while he endeared himself to a numerous circle of acquaintance by his social as well as military virtues.

Maj. BIRDSALL had languished under the wounds he received in defending his country, till within a few weeks of his melancholy exit. He has left a wife and four children to deplore the loss of his support and affection.

......The remains of the brave and lamented Major Birdsall, were interred at Albany, with military honors.

Note....may be buried in Greenbush

East Greenbush was part of the Manor of Rensselaerswyck, and Albany County prior to Rensselaer County's creation in 1791. The town of Clinton was established on February 23, 1855 from the town of Greenbush at the same time as the town of North Greenbush. Three years later on April 14, 1858 the name was changed to East Greenbush by New York State Laws of 1858, Chapter 194. The town originally included land that is now the industrial and residential southend of the city of Rensselaer including Fort Crailo, this was annexed to Rensselaer in 1902.

**********

LIFE OF THURLOW WEED INCLUDING HIS AUTOBIOGRAPHY AND A MEMOIR EMBELLISHED WITH PORTRAITS AND OTHER ILLUSTRATIONS COMPLETE IN TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I.

Soon after my arrival in Albany two events occurred which attracted general interest. On the 4th of July, the remains of General Montgomery, on their way from Quebec to New York, passed through the city. The procession, consisting of the military, civic societies, and citizens of Albany, Troy, and Schenectady, was imposing, impressive, and solemn. The Grand Marshal of the day was Major Benjamin Birdsall of the United States army, who had served gallantly in the war of 1812, and who appeared on that day for the first time without the dressing upon a severe wound in the face that he received in the sortie at Fort Erie, in 1814. On the 12th of the same month, as he was, on a Sunday afternoon, about to review his rifle battalion, he was shot by one of his soldiers. He had passed two hours of that afternoon in our office chatting with two or three friends. After he left the office, I went with a friend for a walk, and returning near sundown, between the patroons and the old arsenal, I heard a rifle shot, and saw a commotion in the cantonment which lay between North Pearl Street and what is now known as the Little Basin. I ran to the spot, and assisted in removing the major (who was my intimate friend) on a litter to his residence in North Pearl Street, where he soon expired.

The excitement against the soldier was so intense that it was difficult to prevent the populace from lynching him. He was committed to the jail, but the feeling ran so high that the civil authorities requested the officer in command at the Greenbush cantonment to receive and protect the prisoner.

Major Birdsall at the commencement of the war resided on a farm which he rented from the patroon, near the Shaker village. He went with a volunteer rifle company, of which he was an officer, to Plattsburgh, where, in the battle that ensued, his gallantry attracted the attention of General Macomb, on whose recommendation, along with that of Governor Tompkins, he was appointed an officer in the United States Rifle Corps, and served subsequently on the Niagara frontier, again distinguishing himself in several battles, until, at the close of the campaign of 1814, he received his desperate wound in leading, under General Peter B. Porter, the assault upon Fort Erie. He had risen, against adverse circumstances, by intelligence and energy, to position and fame, and was justly appreciated by Albanians.

The prisoner, Hamilton, was soon indicted, arraigned, tried, convicted, and sentenced to be hanged. The trial (which I reported for the “Register”) was in the Assembly Chamber, and although Hamilton himself always admitted the charge, and manifested no solicitude for the result of the trial, somebody (his father, it was supposed) employed counsel for him, who strenuously urged an acquittal on the ground of temporary insanity occasioned by liquor, but of course producing no effect.

After his conviction, at the request of Sheriff Hempsted, I went to Hamilton s cell, with a strong feeling of repugnance, which, however, after two or three visits, was, by a revelation of all the circumstances, changed to a sorrowful sympathy. Hamilton was the natural son of a man engaged successfully in a business that ultimately made him wealthy in the city of New York. His mother, turned adrift in disgrace and destitution, struggled as well as she could for a few years, and then left him to the world’s charity.

At the commencement of the war of 1812, then about twenty years old, he enlisted, and it was shown on his trial that he served faithfully and gallantly, receiving at the close of the war an honorable discharge. He had known and greatly admired Major Birdsall during the war. After a year or two of irregularities, with uncertain and precarious employment, he sought Major Birdsall’s recruiting rendezvous and reenlisted. For more than a week before the fatal rifle was fired Hamilton had been intoxicated. On Saturday, a light-colored mulatto, a fine, soldierly-looking young man, who had served during the war, also reenlisted, and was sent to camp to be mustered in; after which, the major intended to take him to his house as a waiter. At mid-day on Sunday Hamilton was told that a negro had been recruited, and as he was, like Hamilton, a tall fellow, was to be put into his platoon and mess. This, maddened as he already was with a mixture of bad whiskey and sour cider, exasperated him beyond control. He loaded his rifle, and went prowling about in search of the “negro,” who, informed of Hamilton’s threats, kept out of his way, until at six o clock Hamilton, with rifle in hand, saw him dodge behind a tent, and started after him. At this moment the major, who was approaching, called, “Hamilton, take your place!” and the rifle, which was ready to be discharged at the soldier, was instantaneously aimed and fatally discharged at the major. In his sober senses, he would have defended Major Birdsall at the risk of his own life.

As a coincidence entitled to be remembered, it is proper to say that Major Birdsall, like the man who assassinated him, was an illegitimate child, unacknowledged until after he had distinguished himself in the war. His father, Colonel Benjamin Birdsall, an officer in the revolutionary army, and an influential citizen of Columbia County, then sent for the major and acknowledged him as a son.

After Hamilton was convicted and sentenced to execution, he requested me to write his “Life and Confession.” He told me that he was the natural son of a wealthy New Yorker, from whom he had received nothing, and whom he never saw; but although he owed him neither affection nor duty, he did not want his father s name made public. The day before his execution he asked permission of the sheriff to walk to the gallows instead of riding, as was usual, on a cart with his coffin. His request was granted. He then asked me to walk near him and witness his execution, that I might see and say that he died like a soldier. It was more than a mile from the jail to the place of execution. The sheriff s posse was escorted by a military company. I walked with the sheriff directly behind Hamilton, whose bearing was that of a soldier, proud of the attention he attracted. He ascended to the scaffold with a firm step, talked cheerfully with the clergyman for a few minutes, said good bye to the multitude, and told the sheriff he was ready. At the fatal moment, when the drop fell, the rope parted, and, to the horror of all present, Hamilton lay stretched upon the ground. But instantly springing to his feet, he stood erect until the sheriff approached him and said, “This is hard, Hamilton.” “Yes,” he replied, “but it is my own fault; I asked you for too much slack.” The sheriff then took a cart-rope, and, handing it to Hamilton, inquired, “Do you think this strong enough? “ Hamilton replied, with a smile, “It is large enough to be strong.” It was then adjusted to his neck, when he reascended, and placed himself upon the drop with a firm foot.

Again the fatal cord was cut, and in a few seconds all was over. That was the first and last execution I ever attended.

Family Members

Advertisement

Advertisement