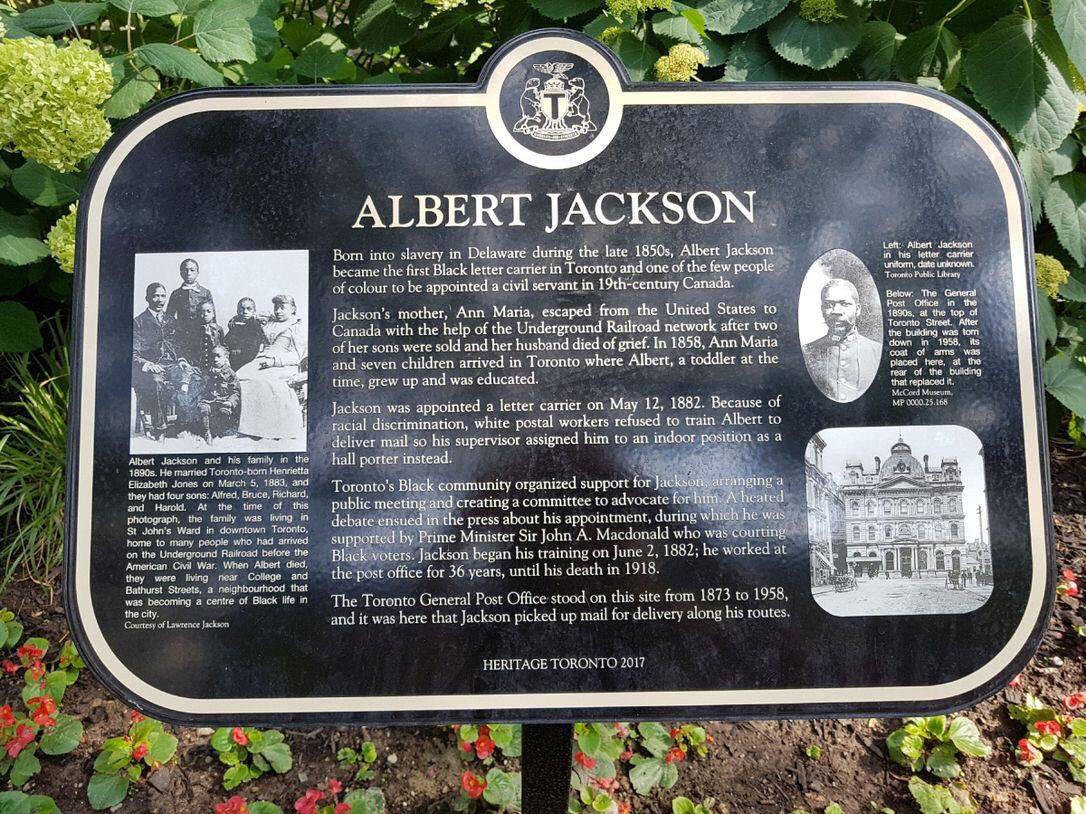

When Ann Maria jackson’s eldest two sons, James and Richard, were sold, she pleaded with her husband to run away and spare their other children a similar fate, writes Frost. But he grew depressed and insane over the loss of his boys and died grief-stricken. In 1858, Ann Maria and her seven other children, the youngest of whom was Albert, escaped to Philadelphia, where African-American abolitionist William Still ran a station of the Underground Railroad, helping fugitive slaves on their journey north to freedom. The family travelled to Toronto and stayed briefly at the home of Thornton and Lucie Blackburn, fugitive slaves from Kentucky who had come to Toronto in 1834. While little is known about the Jacksons’ upbringing, Ann Maria and her family lived in rented rooms in the downtown neighbourhood called St. John’s Ward, the area now bordered by College and Queen Sts., Yonge St. and University Ave. At the time, it’s where newcomers often settled, many in slum like conditions. Ann Maria eked out a living by taking in washing, and sent her children to be educated, says Frost, a researcher at the Harriet Tubman Institute at York University.

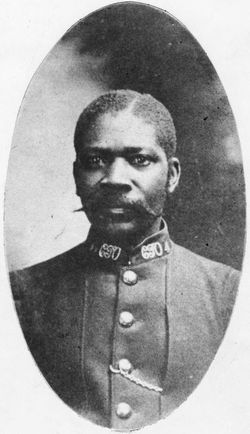

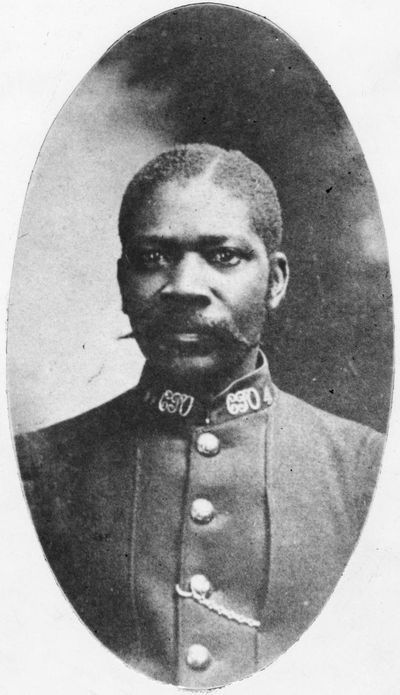

On May 17, The Evening Telegram published a story with the headline “The objectionable African” that described Jackson as “the obnoxious coloured man” and said his appointment elicited “the intense disgust of the existing post office staff.” Two days later, the same newspaper published an editorial stating, “Objection to the young man on account of his colour is indefensible . . . Taxes are not made a penny less to a man because he happens to have dark skin.” For weeks, Jackson’s story played out in the city’s dailies, which ran stories, editorials and letters to the editor. Debate raged in letters to the Toronto World over whether black people were inferior; the newspaper carried an editorial stating that while “inferior races are a fact,” whites and blacks were politically equal. Jackson’s brother John, who helped mobilize the black community, responded with his own letter, which argued that black men were capable of the same accomplishments, when given the same opportunities. His brother Richard, a well-known barber whose clients included businessmen, politicians and publishers, may have also had some influence. The issue was settled in the political arena. In a May 30 editorial the the Evening Telegram noted, “There is at least one time when the assurance is given that coloured people are just as good as people who are white. This is at election time.” That night, a delegation met with prime minister Macdonald, calling on him to intervene. He did. Two days later, The Globe reported, Jackson was out delivering mail, “with no objection being raised.” Jackson’s name vanished from the newspapers and he settled into his life as a letter carrier, and eventually the roles of husband and father. In March 1885, he married Henrietta Jones, with whom he had four sons. As a postman, Jackson likely earned a decent salary, which allowed him to buy property. In 1902, minimum wage for a letter carrier was $1.25 per day; by 1913 it was up to $3. The family’s first home was on Chestnut St., near the British Methodist Episcopal Church, where Jackson was a church leader. In 1914, Jackson purchased a second home, on Brunswick Ave., which he rented. (This is currently the home of Toronto publisher Patrick Crean.) Jackson died on Jan. 14, 1918. His obituary in The Toronto Daily Star described him as a “well-known figure in the downtown district.” Shortly after his death, Henrietta, who lived until age 99, moved to Palmerston Ave., and purchased numerous homes in Harbord Village. So did her sons.

When Ann Maria jackson’s eldest two sons, James and Richard, were sold, she pleaded with her husband to run away and spare their other children a similar fate, writes Frost. But he grew depressed and insane over the loss of his boys and died grief-stricken. In 1858, Ann Maria and her seven other children, the youngest of whom was Albert, escaped to Philadelphia, where African-American abolitionist William Still ran a station of the Underground Railroad, helping fugitive slaves on their journey north to freedom. The family travelled to Toronto and stayed briefly at the home of Thornton and Lucie Blackburn, fugitive slaves from Kentucky who had come to Toronto in 1834. While little is known about the Jacksons’ upbringing, Ann Maria and her family lived in rented rooms in the downtown neighbourhood called St. John’s Ward, the area now bordered by College and Queen Sts., Yonge St. and University Ave. At the time, it’s where newcomers often settled, many in slum like conditions. Ann Maria eked out a living by taking in washing, and sent her children to be educated, says Frost, a researcher at the Harriet Tubman Institute at York University.

On May 17, The Evening Telegram published a story with the headline “The objectionable African” that described Jackson as “the obnoxious coloured man” and said his appointment elicited “the intense disgust of the existing post office staff.” Two days later, the same newspaper published an editorial stating, “Objection to the young man on account of his colour is indefensible . . . Taxes are not made a penny less to a man because he happens to have dark skin.” For weeks, Jackson’s story played out in the city’s dailies, which ran stories, editorials and letters to the editor. Debate raged in letters to the Toronto World over whether black people were inferior; the newspaper carried an editorial stating that while “inferior races are a fact,” whites and blacks were politically equal. Jackson’s brother John, who helped mobilize the black community, responded with his own letter, which argued that black men were capable of the same accomplishments, when given the same opportunities. His brother Richard, a well-known barber whose clients included businessmen, politicians and publishers, may have also had some influence. The issue was settled in the political arena. In a May 30 editorial the the Evening Telegram noted, “There is at least one time when the assurance is given that coloured people are just as good as people who are white. This is at election time.” That night, a delegation met with prime minister Macdonald, calling on him to intervene. He did. Two days later, The Globe reported, Jackson was out delivering mail, “with no objection being raised.” Jackson’s name vanished from the newspapers and he settled into his life as a letter carrier, and eventually the roles of husband and father. In March 1885, he married Henrietta Jones, with whom he had four sons. As a postman, Jackson likely earned a decent salary, which allowed him to buy property. In 1902, minimum wage for a letter carrier was $1.25 per day; by 1913 it was up to $3. The family’s first home was on Chestnut St., near the British Methodist Episcopal Church, where Jackson was a church leader. In 1914, Jackson purchased a second home, on Brunswick Ave., which he rented. (This is currently the home of Toronto publisher Patrick Crean.) Jackson died on Jan. 14, 1918. His obituary in The Toronto Daily Star described him as a “well-known figure in the downtown district.” Shortly after his death, Henrietta, who lived until age 99, moved to Palmerston Ave., and purchased numerous homes in Harbord Village. So did her sons.