But the greatest claim to fame of the class of 1937 is, without a doubt, Mussallem herself. She was a trailblazer, her storied career a microcosm of the evolution of modern nursing. And, along the way, she helped to reshape health care in Canada and nursing education around the world.

Mussallem died on Nov. 9 at Ottawa Hospital Civic Campus surrounded, fittingly, not only by family members, but nurses. She was 98 and suffering from congestive heart failure and pneumonia. Born during the First World War, on Jan. 7 1915, in remote Prince Rupert, BC. Her parents, Lebanese immigrants, later moved to what is now Maple Ridge, BC, where her father was the long-time reeve{the president of a village or town council}and an entrepreneur.

A lively child who excelled in school and helped in the family business, an auto repair shop, she was keenly interested in politics and travelling the world but, at the time, career opportunities for women were limited and, during the Great Depression, money was scarce.

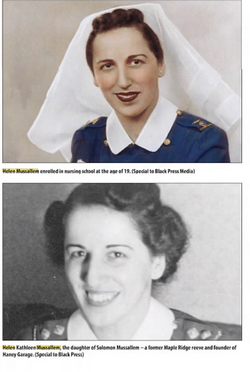

Mussallem enrolled in nursing school in 1934 and, as was the norm at the time, began to practise in the hospital where she was trained.

At the outset of the Second World War, she was quick to enlist, joining the No. 19 Royal Army Medical Corps as a lieutenant. Initially, Mussallem's job was to train medics in basic first aid, but she was keen to do hands-on work and spent the entirety of the war at the front, as a surgical nurse in battlefield hospitals.

"Our job was to patch soldiers up enough to get them back to Canada alive," she recalled in a 1995 interview. Life on the front was very different from staid, hierarchical institutions back home, where nurses in starched white had to stand when a doctor entered the room.

In the army, the work was treacherous and hard but nurses were respected and powerful, unlike their civilian counterparts. She recalled, with amazement, that army surgeons asked her opinion and appreciated her capabilities, and that experience shaped her career.

After the war, Mussallem used her veterans' points – credits that could be used for education and to purchase land – to study at McGill University in Montreal, where she completed a bachelor's degree in nursing. There were only 12 women in the program at the time and, in addition to their studies, they were responsible for training younger hospital nurses. That set Mussallem on a course of lifelong interest in nursing education.

She went on to do a master's degree in education at the University of Washington in Seattle and then did doctoral studies at Columbia University in New York. Mussallem was the first Canadian to get a PhD in nursing, and her thesis, fittingly, was about the need to improve nursing education.

In that period, to finance her studies and her travel, she returned regularly to Vancouver General Hospital, serving in a number of administrative and teaching roles over a decade. But in 1957, she accepted a contract with the Canadian Nurses Association that would change her career path – along with the nursing profession itself and the Canadian health system more broadly. In the postwar years, there were dramatic advances in medicine and massive changes in health-care delivery as the building blocks of medicare were being constructed. But there were no standards for teaching or clinical practice in the country's 25 nursing schools.

Mussallem conducted an exhaustive one-woman inquiry, travelling more than 90,000 kilometres and personally interviewing 2,000 nurses, educators and administrators. Her report, titled Spotlight on Nursing Education, was a bombshell when it was published in 1960. She concluded that education standards were disgraceful and nurses were little more than indentured labour who needed liberating. (Most hospitals trained nurses themselves and forced them to live on-site, guaranteeing themselves a cheap, captive workforce.)

"There was fire coming out of my pen when I was writing that report," Mussallem recalled. The recommendations – to revamp education from top to bottom – infuriated hospital administrators and inflamed nurses. Shortly after the report's publication, nurses at the VGH, her alma mater, walked off the job to demand better work conditions, the first strike by Canadian nurses. A massive unionization movement followed, as did a complete revamp of nursing education.

Mussallem accepted another short-term contract, as executive director of the CNA, but remained in the position for 18 years, from 1963 to 1981. It was a time of dramatic change in health care and she was the face and the voice of nursing.

In 1969, laid up with a serious back injury and frustrated at having to be in hospital, she penned another epic report, titled The Changing Role of the Nurse. It called for a complete revamp of primary care, replacing the solo family doctor with nurse-led clinics in shopping malls, nursing homes, community centres and other places people congregate. It served as the model for the creation of a network of community health clinics in Quebec know as CLSCs, but was generally ignored elsewhere until recently, when nurse-led clinics have become in vogue.

During Mussallem's tenure at CNA, the role of nurses changed substantially. "Nursing moved from being a vocation to being a profession and Helen led that change," says Barbara Mildon, the current president of the CNA.

The role and rights of women in Canadian society also changed markedly in that period. As a nurse who had tended to far too many desperate women who had undergone back-alley abortions, Mussallem was outspoken in her support for reproductive rights, including access to birth control and abortion (both of which were illegal).

She said her proudest achievement was helping to shape a publicly funded health-care system, or medicare.

"I lived in an era when patients died because they didn't have money to pay for medical services, and I'm proud to say I played a role in ending that injustice, in creating a system for everyone."

Helen never married and rarely discussed her relationships. The exception was the great love of her life, Dr. J. Wendell McLeod. A pioneer in social medicine and medical education, he and Helen were together for many years and remained good friends even after they separated.

In Wendell's book ... J. Wendell Macleod: Saskatchewan's Red Dean by Louis Horlick .. Chapter Ten Macleod and Helen (pp. 122-126) MACLEOD met Helen MUSSALLEM shortly after his arrival in Ottawa in 1962. They were both active in national medical bodies, he with the AGMC and she with the Canadian Nurses Association. Macleod first refers to her in his diary on 19 February 1965: "Te deum— MacFarlane Report emerges from Queen's Printer. Jubilant lunch with Bernard Blishen and Helen Mussallem." In FEB 1974 Hazen Sise died suddenly of a pulmonary embolus resulting from thrombophlebitis. He left behind his wife, Jolanta ('Jola'), and a young son, Hazen ('Hadie'). Macleod wrote that he was 'shocked by the tragedy. Hazen had so much yet left to do.' Jola and Macleod had met in Ottawa in 1972, and 'then, of course, we went to China in 1973.' Alert to the family's distress, Macleod began to spend a great deal of time with Jola. Helen Mussallem considered his attention excessive.

While Mussallem was passionate, she was soft-spoken. Her regal demeanour was disarming and misleading. She was always impeccably coiffed, dressed, and bejewelled, almost never without elegant gloves and hat. But when she took off the gloves – literally and figuratively – she was unrelenting. "I was always in a scrap over something and I didn't lose very often," she once said.

Education was always her abiding passion. She created the Canadian Nurses Foundation as a charity that would provide scholarships for nurses.

At the CNF's 40th anniversary celebrations in May, it was noted that the Helen K. Mussallem Fellowship alone had provided 1,500 scholarships to nurses pursuing a master's degree. And, needless to say, she was at the event, working the room, encouraging donations.

Mussallem retired from the CNA at 66, but she was not the type to sit at home and knit. Instead, she undertook a second career as a roving ambassador for nursing.

She travelled the world, essentially reprising what she had done in Canada decades earlier, dissecting the nursing education system and recommending changes to make nursing more professional – a task she performed in 40 countries.

"What I remember most about my aunt is always meeting her at the airport," says Dr. Lynette Harper, her niece. "She was always travelling somewhere – the Caribbean, Africa, Russia, Lebanon. She never stopped."

Mussallem took a brief break from her international travel to serve as president of the venerable Victorian Order of Nurses, from 1989-91, but soon grew restless and hit the road again.

Her renown grew and she reaped much recognition, earning her the unofficial title of Canada's most decorated nurse. In 1969, she was made an officer of the Order of Canada and was promoted to companion in 1992.

She was also Dame of Grace for the Venerable Order of Saint John, a chivalry order associated with St. John Ambulance.

Mussallem was the first nurse outside Britain to be honoured as Fellow of the Royal College of Nursing. In the citation, she was described as "Canada's most distinguished nurse of her time and generation." But her proudest moment was receiving the Florence Nightingale Medal – the highest award of the International Red Cross Society.

She also received honorary degrees from six universities, but always downplayed the personal accolades, saying they were intended and truly belonged to nurses who toil anonymously on the front lines every day.

"Nobody contributes more to the health of Canadians than nurses," she said.

Helen was considered to be one of the top nurses in the world and spent many years working with the World Health Organization developing nursing and triage systems for underdeveloped nations. She remained active until her passing in 2012.

Mussallem is predeceased by her parents, Solomon and Annie Mussallem, and her siblings George, Mary, Nicholas, Peter and Lily.

A memorial service has been held in Ottawa, and she asked that any donations in her honour go to the Canadian Nurses Foundation.

Henry Norman Bethune

___________________________

Dr. Helen Kathleen Mussallem, Ed.D, CC, FRCN, DGStJ (7 January 1915 – 9 November 2012) was a noted, decorated Canadian nurse, who served in the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps during World War II.

Life

Born in Prince Rupert, British Columbia to Solomon and Annie (née Besytt) Mussallem, both of Lebanese descent, Mussallem studied at the School of Nursing, Vancouver General Hospital from 1934 to 1937. Between 1943 and 1946, she served as a surgical nurse and lieutenant in the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps during World War II. In 1947, she attended McGill University, where she received her Bachelor's Degree in Nursing. She received her Master's of Arts in Education from Columbia University Teachers College and was the first Canadian nurse to earn a doctoral degree from Columbia University. From 1963–81, she was Executive Director of the Canadian Nurses Association. From 1989–91 she was the President of the Victorian Order of Nurses. Mussallem died in Ottawa at the age of 97 on 9 November 2012.

Honours

She was the first nurse outside the United Kingdom to be honoured as a Fellow of the Royal College of Nursing.

She received the highest award that can be awarded by the International Red Cross, the Florence Nightingale Medal.

In 1982, she was appointed Dame of Grace of the Venerable Order of Saint John.

In 1969, she was made an Officer of the Order of Canada and was promoted to Companion in 1992.

In 2006, she was appointed Capilano Herald Extraordinary within the Canadian Heraldic Authority. Capilano Herald Extraordinary Helen Mussallem (2006–2012)

She received honorary degrees from Memorial University, the University of New Brunswick, Queen's University, McMaster University, and the University of British Columbia

http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=f&ProjectID=595&ProjectElementID=2099

But the greatest claim to fame of the class of 1937 is, without a doubt, Mussallem herself. She was a trailblazer, her storied career a microcosm of the evolution of modern nursing. And, along the way, she helped to reshape health care in Canada and nursing education around the world.

Mussallem died on Nov. 9 at Ottawa Hospital Civic Campus surrounded, fittingly, not only by family members, but nurses. She was 98 and suffering from congestive heart failure and pneumonia. Born during the First World War, on Jan. 7 1915, in remote Prince Rupert, BC. Her parents, Lebanese immigrants, later moved to what is now Maple Ridge, BC, where her father was the long-time reeve{the president of a village or town council}and an entrepreneur.

A lively child who excelled in school and helped in the family business, an auto repair shop, she was keenly interested in politics and travelling the world but, at the time, career opportunities for women were limited and, during the Great Depression, money was scarce.

Mussallem enrolled in nursing school in 1934 and, as was the norm at the time, began to practise in the hospital where she was trained.

At the outset of the Second World War, she was quick to enlist, joining the No. 19 Royal Army Medical Corps as a lieutenant. Initially, Mussallem's job was to train medics in basic first aid, but she was keen to do hands-on work and spent the entirety of the war at the front, as a surgical nurse in battlefield hospitals.

"Our job was to patch soldiers up enough to get them back to Canada alive," she recalled in a 1995 interview. Life on the front was very different from staid, hierarchical institutions back home, where nurses in starched white had to stand when a doctor entered the room.

In the army, the work was treacherous and hard but nurses were respected and powerful, unlike their civilian counterparts. She recalled, with amazement, that army surgeons asked her opinion and appreciated her capabilities, and that experience shaped her career.

After the war, Mussallem used her veterans' points – credits that could be used for education and to purchase land – to study at McGill University in Montreal, where she completed a bachelor's degree in nursing. There were only 12 women in the program at the time and, in addition to their studies, they were responsible for training younger hospital nurses. That set Mussallem on a course of lifelong interest in nursing education.

She went on to do a master's degree in education at the University of Washington in Seattle and then did doctoral studies at Columbia University in New York. Mussallem was the first Canadian to get a PhD in nursing, and her thesis, fittingly, was about the need to improve nursing education.

In that period, to finance her studies and her travel, she returned regularly to Vancouver General Hospital, serving in a number of administrative and teaching roles over a decade. But in 1957, she accepted a contract with the Canadian Nurses Association that would change her career path – along with the nursing profession itself and the Canadian health system more broadly. In the postwar years, there were dramatic advances in medicine and massive changes in health-care delivery as the building blocks of medicare were being constructed. But there were no standards for teaching or clinical practice in the country's 25 nursing schools.

Mussallem conducted an exhaustive one-woman inquiry, travelling more than 90,000 kilometres and personally interviewing 2,000 nurses, educators and administrators. Her report, titled Spotlight on Nursing Education, was a bombshell when it was published in 1960. She concluded that education standards were disgraceful and nurses were little more than indentured labour who needed liberating. (Most hospitals trained nurses themselves and forced them to live on-site, guaranteeing themselves a cheap, captive workforce.)

"There was fire coming out of my pen when I was writing that report," Mussallem recalled. The recommendations – to revamp education from top to bottom – infuriated hospital administrators and inflamed nurses. Shortly after the report's publication, nurses at the VGH, her alma mater, walked off the job to demand better work conditions, the first strike by Canadian nurses. A massive unionization movement followed, as did a complete revamp of nursing education.

Mussallem accepted another short-term contract, as executive director of the CNA, but remained in the position for 18 years, from 1963 to 1981. It was a time of dramatic change in health care and she was the face and the voice of nursing.

In 1969, laid up with a serious back injury and frustrated at having to be in hospital, she penned another epic report, titled The Changing Role of the Nurse. It called for a complete revamp of primary care, replacing the solo family doctor with nurse-led clinics in shopping malls, nursing homes, community centres and other places people congregate. It served as the model for the creation of a network of community health clinics in Quebec know as CLSCs, but was generally ignored elsewhere until recently, when nurse-led clinics have become in vogue.

During Mussallem's tenure at CNA, the role of nurses changed substantially. "Nursing moved from being a vocation to being a profession and Helen led that change," says Barbara Mildon, the current president of the CNA.

The role and rights of women in Canadian society also changed markedly in that period. As a nurse who had tended to far too many desperate women who had undergone back-alley abortions, Mussallem was outspoken in her support for reproductive rights, including access to birth control and abortion (both of which were illegal).

She said her proudest achievement was helping to shape a publicly funded health-care system, or medicare.

"I lived in an era when patients died because they didn't have money to pay for medical services, and I'm proud to say I played a role in ending that injustice, in creating a system for everyone."

Helen never married and rarely discussed her relationships. The exception was the great love of her life, Dr. J. Wendell McLeod. A pioneer in social medicine and medical education, he and Helen were together for many years and remained good friends even after they separated.

In Wendell's book ... J. Wendell Macleod: Saskatchewan's Red Dean by Louis Horlick .. Chapter Ten Macleod and Helen (pp. 122-126) MACLEOD met Helen MUSSALLEM shortly after his arrival in Ottawa in 1962. They were both active in national medical bodies, he with the AGMC and she with the Canadian Nurses Association. Macleod first refers to her in his diary on 19 February 1965: "Te deum— MacFarlane Report emerges from Queen's Printer. Jubilant lunch with Bernard Blishen and Helen Mussallem." In FEB 1974 Hazen Sise died suddenly of a pulmonary embolus resulting from thrombophlebitis. He left behind his wife, Jolanta ('Jola'), and a young son, Hazen ('Hadie'). Macleod wrote that he was 'shocked by the tragedy. Hazen had so much yet left to do.' Jola and Macleod had met in Ottawa in 1972, and 'then, of course, we went to China in 1973.' Alert to the family's distress, Macleod began to spend a great deal of time with Jola. Helen Mussallem considered his attention excessive.

While Mussallem was passionate, she was soft-spoken. Her regal demeanour was disarming and misleading. She was always impeccably coiffed, dressed, and bejewelled, almost never without elegant gloves and hat. But when she took off the gloves – literally and figuratively – she was unrelenting. "I was always in a scrap over something and I didn't lose very often," she once said.

Education was always her abiding passion. She created the Canadian Nurses Foundation as a charity that would provide scholarships for nurses.

At the CNF's 40th anniversary celebrations in May, it was noted that the Helen K. Mussallem Fellowship alone had provided 1,500 scholarships to nurses pursuing a master's degree. And, needless to say, she was at the event, working the room, encouraging donations.

Mussallem retired from the CNA at 66, but she was not the type to sit at home and knit. Instead, she undertook a second career as a roving ambassador for nursing.

She travelled the world, essentially reprising what she had done in Canada decades earlier, dissecting the nursing education system and recommending changes to make nursing more professional – a task she performed in 40 countries.

"What I remember most about my aunt is always meeting her at the airport," says Dr. Lynette Harper, her niece. "She was always travelling somewhere – the Caribbean, Africa, Russia, Lebanon. She never stopped."

Mussallem took a brief break from her international travel to serve as president of the venerable Victorian Order of Nurses, from 1989-91, but soon grew restless and hit the road again.

Her renown grew and she reaped much recognition, earning her the unofficial title of Canada's most decorated nurse. In 1969, she was made an officer of the Order of Canada and was promoted to companion in 1992.

She was also Dame of Grace for the Venerable Order of Saint John, a chivalry order associated with St. John Ambulance.

Mussallem was the first nurse outside Britain to be honoured as Fellow of the Royal College of Nursing. In the citation, she was described as "Canada's most distinguished nurse of her time and generation." But her proudest moment was receiving the Florence Nightingale Medal – the highest award of the International Red Cross Society.

She also received honorary degrees from six universities, but always downplayed the personal accolades, saying they were intended and truly belonged to nurses who toil anonymously on the front lines every day.

"Nobody contributes more to the health of Canadians than nurses," she said.

Helen was considered to be one of the top nurses in the world and spent many years working with the World Health Organization developing nursing and triage systems for underdeveloped nations. She remained active until her passing in 2012.

Mussallem is predeceased by her parents, Solomon and Annie Mussallem, and her siblings George, Mary, Nicholas, Peter and Lily.

A memorial service has been held in Ottawa, and she asked that any donations in her honour go to the Canadian Nurses Foundation.

Henry Norman Bethune

___________________________

Dr. Helen Kathleen Mussallem, Ed.D, CC, FRCN, DGStJ (7 January 1915 – 9 November 2012) was a noted, decorated Canadian nurse, who served in the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps during World War II.

Life

Born in Prince Rupert, British Columbia to Solomon and Annie (née Besytt) Mussallem, both of Lebanese descent, Mussallem studied at the School of Nursing, Vancouver General Hospital from 1934 to 1937. Between 1943 and 1946, she served as a surgical nurse and lieutenant in the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps during World War II. In 1947, she attended McGill University, where she received her Bachelor's Degree in Nursing. She received her Master's of Arts in Education from Columbia University Teachers College and was the first Canadian nurse to earn a doctoral degree from Columbia University. From 1963–81, she was Executive Director of the Canadian Nurses Association. From 1989–91 she was the President of the Victorian Order of Nurses. Mussallem died in Ottawa at the age of 97 on 9 November 2012.

Honours

She was the first nurse outside the United Kingdom to be honoured as a Fellow of the Royal College of Nursing.

She received the highest award that can be awarded by the International Red Cross, the Florence Nightingale Medal.

In 1982, she was appointed Dame of Grace of the Venerable Order of Saint John.

In 1969, she was made an Officer of the Order of Canada and was promoted to Companion in 1992.

In 2006, she was appointed Capilano Herald Extraordinary within the Canadian Heraldic Authority. Capilano Herald Extraordinary Helen Mussallem (2006–2012)

She received honorary degrees from Memorial University, the University of New Brunswick, Queen's University, McMaster University, and the University of British Columbia

http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=f&ProjectID=595&ProjectElementID=2099

Gravesite Details

Maple Ridge Cemetery with family