13 Aug 1972, Sun

Page 56

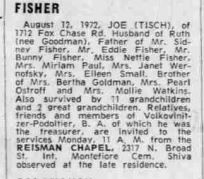

Name: Joseph Fisher

Last Residence: 19152 Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

BORN: 1 Sep 1900

Died: Aug 1972

State (Year) SSN issued: Pennsylvania (Before 1951)

Been There, Done That

By Eddie Fisher and David Fisher, 1999

My father was mad at his life. He worked hard and had nothing to show for it, so he took it out on his family, especially my mother and my oldest brother, Sid. My father was a nasty, abusive man, a tyrant. I never saw him hit my mother, though my brothers and sisters insisted he did. But I know I saw him hit my brother. I'm not sure that really mattered, because the verbal abuse was just as bad. I'll never forget the sound that came out of his mouth: loud and shrill and nasty. There was nothing nice about it. It was a sound that seemed strong enough to drill right through the walls. When he started yelling, I'd be so embarrassed I'd run and close the windows and hope that no one would hear him. When I finally left home, my little sister, Eileen, became the window closer. The only thing my mother ever wanted from my father was a divorce, and as soon as her children were old enough, she left him.

My parents were part of the massive wave of Russian Jews who came to America around the turn of the century to escape the poverty and the pogroms of Eastern Europe. My father, Joe, was thirteen years old when he immigrated. My father's family name was Tisch or Fisch, but it became Fisher when he landed in America and got his papers. My father's family never accepted my mother and never had too much to do with us until I became famous. Then they would come to the nightclubs and proudly sit right in the front. I was told they felt that my mother's family was too poor. Too poor? Maybe the big difference was that the Fishers' house had a porch. The only time I ever heard the Fishers say anything kind about my mother was in the limousine on the way to her funeral.

When they married, my mother was fifteen years old, my father almost eighteen. They were just kids. My father was an intelligent man, and he had been educated in Russia. He loved to read, he loved history; it was real life that gave him problems. Both of them had been forced to drop out of school to help support their families, so they got married and had their own family they couldn't support. My father never really had a chance. I suppose that's why I always felt so sorry for him.

The 1929 stock market crash and the Great Depression barely affected my family. We had nothing to start with, so we had nothing to lose. My father worked in leather factories long before the unions created decent working conditions. These places were hot and dirty and the pay was terrible, but nobody dared complain. People like my father, immigrants with little formal education and limited technical skills, were happy to have any job. I remember going with him to work one day. Although he never said anything to me, I think he wanted me to see for myself what his life was all about. At that time he was making leather suitcases. The "factory" was a sweatshop; it was dark and filthy and dangerous. People didn't matter, production did; how many pieces a day. I couldn't believe how hard he worked, how much muscle it took to make a cheap suitcase. I didn't vow that day that I would never work in a place like that, nothing dramatic like that, because that possibility never occurred to me. I had been born with magic in my throat, I was going to be a singer. There was never a day that I doubted that.

In 1934 my father was in a terrible automobile accident. The driver collided with an ice-delivery truck and was killed, and my father was badly hurt. For several weeks it looked like he was going to die. But he lived and collected almost $5,000 in insurance. That was a fortune, and for just a little while, we were rich. Imagine that, a car wreck was the best opportunity my father ever had. He used the money to open Fisher's Delicatessen. Most of the family worked there. My father wore a clean white apron and ran the place, the children stocked the shelves and cleaned up, my mother cooked the meats and made the potato salad. It was the only time in my childhood that I remember my father being happy. But it didn't last very long. We didn't know how to run a grocery store, and even my mother's wonderful potato salad wasn't enough to keep us in business. It only took us about a year to lose the entire insurance settlement.

After that, my father peddled fruits and vegetables from the back of an old LaSalle or Packard. He took out the back seat and drove down to the wholesale market on the docks and bought leftover peaches and tomatoes and whatever else was in season. Every penny had to count. He'd empty the boxes of strawberries and then refill them, putting the rotten ones on the bottom so they wouldn't be seen, then squeeze the corners of the boxes so it would take fewer berries to fill them. He'd use every trick to make a few pennies. I was so embarrassed; I hated him for making me feel dishonest.

My brother Sol and I would fill baskets from the back seat then walk through the alleys between the buildings, singing as loudly as we could to attract attention. We sang the songs of produce peddlers: "Sound, ripe tomatoes here, ten cents a quarter peck ..." Housewives would lower their baskets from their windows; we'd fill them with whatever we had, and they'd give us a few pennies. I was a skinny little kid and, supposedly, these women would see me and feel so sorry for me that they would put food in their baskets for me when they lowered them. Years later, after I'd become a big star, after I was able to afford to go to Hong Kong and buy 140 silk suits, 185 monogrammed silk shirts, and 50 pair of silk pajamas, after I was able to give a forty-carat diamond bracelet to Elizabeth, this was the story my mother most enjoyed telling reporters.

We lived surrounded by poverty. Our neighbors were just like us, Jewish immigrants struggling to survive. But even in that world I still felt like everybody else was rich and we were poor. To my mother's great shame, we had to go on "the dole"—we had to accept welfare several times: seventeen dollars and fifty cents a week. For food and used clothing we had to go to the distribution center set up in an abandoned railroad station. My mother was so embarrassed that the neighbors would know that we were "on relief" that she would put a pillow in the baby carriage, cover it with a net, and make me wheel it to the welfare center. Then she'd fill the carriage with flour and potatoes and whatever they gave us, cover it again, and I would wheel it home. I always pushed the carriage through the rear alleys so no one would see us.

There were many times we couldn't pay the rent, so at night we would pack the few pieces of furniture we had and our ragged clothes, and move someplace where the landlord didn't know we were broke. The place I remember most of all was a tiny house with two bedrooms and one bathroom. I slept in a bed with my two brothers. There was only enough hot water for one bath, so we'd fill the tub and all nine of us would use the same water. The toilet flushed only once, then it couldn't be used for a long time. It was tough, very tough. When I was fourteen years old I began staying with the family of a man named Skipper Dawes, who had discovered me and put me on radio. His house was warm in the winter and dry when it rained, and it had a real shower, but the thing that most amazed me was that his toilets refilled with water after being flushed. I used to go into the bathroom just to flush the toilet several times.

13 Aug 1972, Sun

Page 56

Name: Joseph Fisher

Last Residence: 19152 Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

BORN: 1 Sep 1900

Died: Aug 1972

State (Year) SSN issued: Pennsylvania (Before 1951)

Been There, Done That

By Eddie Fisher and David Fisher, 1999

My father was mad at his life. He worked hard and had nothing to show for it, so he took it out on his family, especially my mother and my oldest brother, Sid. My father was a nasty, abusive man, a tyrant. I never saw him hit my mother, though my brothers and sisters insisted he did. But I know I saw him hit my brother. I'm not sure that really mattered, because the verbal abuse was just as bad. I'll never forget the sound that came out of his mouth: loud and shrill and nasty. There was nothing nice about it. It was a sound that seemed strong enough to drill right through the walls. When he started yelling, I'd be so embarrassed I'd run and close the windows and hope that no one would hear him. When I finally left home, my little sister, Eileen, became the window closer. The only thing my mother ever wanted from my father was a divorce, and as soon as her children were old enough, she left him.

My parents were part of the massive wave of Russian Jews who came to America around the turn of the century to escape the poverty and the pogroms of Eastern Europe. My father, Joe, was thirteen years old when he immigrated. My father's family name was Tisch or Fisch, but it became Fisher when he landed in America and got his papers. My father's family never accepted my mother and never had too much to do with us until I became famous. Then they would come to the nightclubs and proudly sit right in the front. I was told they felt that my mother's family was too poor. Too poor? Maybe the big difference was that the Fishers' house had a porch. The only time I ever heard the Fishers say anything kind about my mother was in the limousine on the way to her funeral.

When they married, my mother was fifteen years old, my father almost eighteen. They were just kids. My father was an intelligent man, and he had been educated in Russia. He loved to read, he loved history; it was real life that gave him problems. Both of them had been forced to drop out of school to help support their families, so they got married and had their own family they couldn't support. My father never really had a chance. I suppose that's why I always felt so sorry for him.

The 1929 stock market crash and the Great Depression barely affected my family. We had nothing to start with, so we had nothing to lose. My father worked in leather factories long before the unions created decent working conditions. These places were hot and dirty and the pay was terrible, but nobody dared complain. People like my father, immigrants with little formal education and limited technical skills, were happy to have any job. I remember going with him to work one day. Although he never said anything to me, I think he wanted me to see for myself what his life was all about. At that time he was making leather suitcases. The "factory" was a sweatshop; it was dark and filthy and dangerous. People didn't matter, production did; how many pieces a day. I couldn't believe how hard he worked, how much muscle it took to make a cheap suitcase. I didn't vow that day that I would never work in a place like that, nothing dramatic like that, because that possibility never occurred to me. I had been born with magic in my throat, I was going to be a singer. There was never a day that I doubted that.

In 1934 my father was in a terrible automobile accident. The driver collided with an ice-delivery truck and was killed, and my father was badly hurt. For several weeks it looked like he was going to die. But he lived and collected almost $5,000 in insurance. That was a fortune, and for just a little while, we were rich. Imagine that, a car wreck was the best opportunity my father ever had. He used the money to open Fisher's Delicatessen. Most of the family worked there. My father wore a clean white apron and ran the place, the children stocked the shelves and cleaned up, my mother cooked the meats and made the potato salad. It was the only time in my childhood that I remember my father being happy. But it didn't last very long. We didn't know how to run a grocery store, and even my mother's wonderful potato salad wasn't enough to keep us in business. It only took us about a year to lose the entire insurance settlement.

After that, my father peddled fruits and vegetables from the back of an old LaSalle or Packard. He took out the back seat and drove down to the wholesale market on the docks and bought leftover peaches and tomatoes and whatever else was in season. Every penny had to count. He'd empty the boxes of strawberries and then refill them, putting the rotten ones on the bottom so they wouldn't be seen, then squeeze the corners of the boxes so it would take fewer berries to fill them. He'd use every trick to make a few pennies. I was so embarrassed; I hated him for making me feel dishonest.

My brother Sol and I would fill baskets from the back seat then walk through the alleys between the buildings, singing as loudly as we could to attract attention. We sang the songs of produce peddlers: "Sound, ripe tomatoes here, ten cents a quarter peck ..." Housewives would lower their baskets from their windows; we'd fill them with whatever we had, and they'd give us a few pennies. I was a skinny little kid and, supposedly, these women would see me and feel so sorry for me that they would put food in their baskets for me when they lowered them. Years later, after I'd become a big star, after I was able to afford to go to Hong Kong and buy 140 silk suits, 185 monogrammed silk shirts, and 50 pair of silk pajamas, after I was able to give a forty-carat diamond bracelet to Elizabeth, this was the story my mother most enjoyed telling reporters.

We lived surrounded by poverty. Our neighbors were just like us, Jewish immigrants struggling to survive. But even in that world I still felt like everybody else was rich and we were poor. To my mother's great shame, we had to go on "the dole"—we had to accept welfare several times: seventeen dollars and fifty cents a week. For food and used clothing we had to go to the distribution center set up in an abandoned railroad station. My mother was so embarrassed that the neighbors would know that we were "on relief" that she would put a pillow in the baby carriage, cover it with a net, and make me wheel it to the welfare center. Then she'd fill the carriage with flour and potatoes and whatever they gave us, cover it again, and I would wheel it home. I always pushed the carriage through the rear alleys so no one would see us.

There were many times we couldn't pay the rent, so at night we would pack the few pieces of furniture we had and our ragged clothes, and move someplace where the landlord didn't know we were broke. The place I remember most of all was a tiny house with two bedrooms and one bathroom. I slept in a bed with my two brothers. There was only enough hot water for one bath, so we'd fill the tub and all nine of us would use the same water. The toilet flushed only once, then it couldn't be used for a long time. It was tough, very tough. When I was fourteen years old I began staying with the family of a man named Skipper Dawes, who had discovered me and put me on radio. His house was warm in the winter and dry when it rained, and it had a real shower, but the thing that most amazed me was that his toilets refilled with water after being flushed. I used to go into the bathroom just to flush the toilet several times.

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement