Despite repeated complaints to authorities by family members and doctors, authorities placed him back with his father, which resulted in more beatings to little Matthew Eli Creekmore.

CPS had removed Eli from his home in Everett three times in two years. He was returned home each time despite evidence of continued abuse by his father. The state Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) concluded Eli's caseworkers made no major errors in the handling of this case. DSHS officials said the "system" failed Eli, and recommended changes in law and policy.

Matthew Eli's father was convicted of second degree murder and sentenced to 60 years in prison for kicking his son to death. Matthew Eli's mother was sentenced to ten years. Legislation was changed and there was an overhaul of child welfare laws as a result of the horrific case of Matthew Eli Creekmore.

--

By TIMOTHY EGAN, Special to the New York Times - Published: January 1, 1988

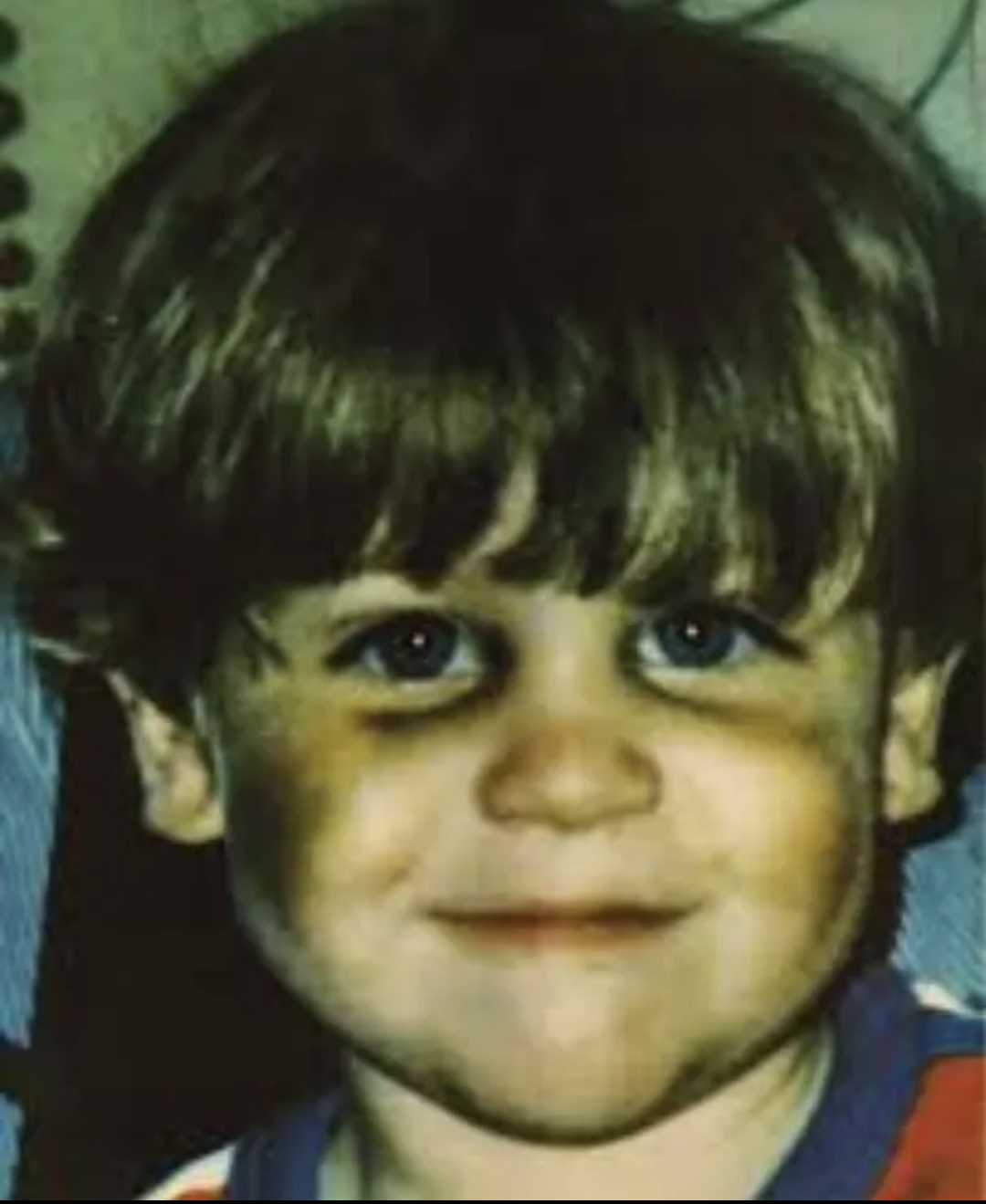

SEATTLE, Dec. 31, 1988 — The swollen eyes of a 3-year-old boy, bruised and battered repeatedly by his father despite intervention from state social workers, stare out from a snapshot that continues to haunt people in the Pacific Northwest.

The boy, Matthew Eli Creekmore, was kicked to death by his father, Darren Creekmore, more than a year ago. But the case is just beginning to have national repercussions as legislatures around the country study a sweeping overhaul of the child welfare laws in the State of Washington that came about as a result of the clamor over the child's death.

The rumblings of change come in the aftermath of a 200 percent increase nationally in reported cases of child abuse in the last decade, and they follow public outrage over cases like the Creekmore killing here and the fatal beating of 6-year-old Elizabeth Steinberg in Manhattan last November. An Issue of Top Priority

National experts monitoring the growing problem say that reform of child abuse laws is shaping up as a top priority for state legislatures in the coming year.

After a long trend toward keeping troubled families together, sometimes at the expense of an abused child, states like Washington are reversing previous laws and making protection of the child the paramount concern. In another change, social workers here do not have to wait for substantiated harm before removing a child from the home but can intervene on the basis of the potential risk of abuse.

This state also recently passed a pioneering law that makes child abuse resulting in death the equivalent of first-degree murder. Under this ''homicide by abuse'' law, prosecutors no longer have to prove premeditation or intent to kill to win a conviction. Instead, they must show that the abusive parent displayed ''extreme indifference to human life.''

''Premeditation in child abuse cases is almost impossible to prove,'' said State Senator Stuart Halson, who drafted the law. ''This gets us around that oft-heard defense: 'I didn't mean to kill the boy; I just wanted to discipline him.' '' Other States Study Law

The new law is being studied by a number of states, including New York, where about 100 children a year die from child abuse, according to a spokesman for the Department of Social Services. Experts estimate that nationwide from 2,000 to 5,000 children die each year as a result of abuse. Officially, there was a 23 percent increase in child abuse deaths from 1985 to 1986.

Nationally, ''there is a real crisis going on now in every state,'' said Susan Robison of the National Conference of State Legislatures, which is based in Denver. Reflecting concern about the 2.2 million abuse and neglect cases reported nationally in 1986, many states have recently enacted tightened child welfare laws. But at the same time there is a countertrend toward more legal rights for parents who are accused of abusing children.

For example, while Washington State, in its sweeping 1987 overhaul of child protection laws, gave social workers the right to interview children without notifying their parents beforehand, several members of the Colorado Legislature introduced a bill to allow parents greater legal representation in abuse investigations. That bill was voted down, but its supporters are planning to re-introduce it.

Every state now has some sort of mandatory reporting law, requiring doctors, health or day care workers who come in contact with an abused child to tell the authorities about it, but ''there is still a tremendous amount of under-reporting of abuse going on,'' said Patricia Toth, director of the National Center for the Prosecution of Child Abuse, in Alexandria, Va. Rise in Abuse Cases

Ms. Toth attributes the 200 percent increase in reported child abuse to ''a combination of increased awareness, mandatory reporting laws and perhaps a general rise in parental abuse.''

Ms. Toth said cases such as the Steinberg and Creekmore deaths ''are the catalysts for more change.''

''The country will go along, basically unaware, and then something very awful happens to grab everybody's attention,'' she said.

Deborah Daro, research director of the National Committee for the Prevention of Child Abuse, which is based in Chicago, said that after the news of Elizabeth Steinberg's death, ''There was a response like we'd never seen before, an outpouring of outrage, our phones ringing off the hook with people asking 'why,' ''

In the Washington case, social workers from the state Child Protective Services had removed the 3-year-old boy from his home in Everett three times in the 10 months before he died. But each time they returned him, despite reports from his grandmother, doctors and day-care teachers that he was being abused. His father had twice been charged with beating the boy.

At the time of the boy's death, state officials had determined that the family was making an effort to improve the situation. But on Sept. 27, 1986, the boy was kicked repeatedly in the stomach and then left to die in his bedroom. Mr. Creekmore was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to 60 years in prison, one of the most severe sentences in recent memory for such a crime. The boy's mother, Mary Creekmore, testified for the state and was allowed to plead guilty to a gross misdemeanor charge of failing to get medical attention for the child.

When the case first came to light last year, hundreds of parents demonstrated outside the social service headquarters in Everett and Olympia, the state capital, demanding that the system be overhauled. They were soon joined by Child Protective Service workers, who said inadequate financing and understaffing had contributed to what the state social service director admitted was ''a breakdown of the system.''

The case, while not unique by national standards, was an example of problems facing overburdened child welfare workers around the country. Nationally, while reported cases of child abuse rose 156 percent from 1981 to 1986, state financing to attack the problem rose a mere 2 percent, according to a recent Congressional study.

''In probably every state in the country, you've got child protection workers not going out on a lot of cases except the high priority ones, and that in itself is very dangerous,'' said Patricia Schene, director of the American Association for the Protection of Children, based in Denver.

''What's clear is that there are bad decisions being made because the system is overloaded, and that means we'll see a lot more foment in the next year or two,'' she said. A lurking problem, she said, is the dearth of foster homes. While the public and state officials are calling for more abused children to be removed from their homes, they have yet to provide adequate money to attract foster parents for those children.

In Washington, because of the fallout from the Creekmore case, more than 5,000 children were removed from their homes in the last year, but officials could only find 3,800 foster homes in which to place those children.

But increased public concern has also led to more private charity. Following the furor over young Eli's death, a new $1.3 million private center for abused children, the Eli Creekmore Memorial Center, was opened near Seattle last month.

In dedicating the center, its director, Patrick Gogerty said, ''In death, his voice became a mighty shout that stirred the conscience of all the people in the state of Washington.'

--

10/17/1990 - EVERETT - With yesterday's announcement of her $185,500 settlement with the state of Washington, Eli Creekmore's grandmother wanted to talk about the future.

`I don't have to go through specific incidents of Eli's death anymore,'' Myrna Struchen Johnson said after a hearing where the settlement was approved. ``But I can certainly go forward and try to stop what I can of the abuse of other children.''

The brief, quiet hearing in Snohomish County Superior Court was in sharp contrast to the outcry generated by Eli's death in 1986.

People across the state reacted with horror and disbelief after 3-year-old Eli was kicked to death by his father, especially because Child Protective Services employees had evidence the child had previously been abused by his father.

Darren Creekmore received a 60-year sentence for murdering his son. Mary Creekmore, Eli's mother and Johnson's daughter, pleaded guilty to failing to get her son medical attention.

The state Department of Social and Health Services concluded a flawed system failed Eli, and worked to change policies and pass new laws.

But Johnson's wrongful death lawsuit challenged that conclusion and alleged that the state and two of its employees negligently handled her grandson's case.

The state, without admitting wrongdoing, agreed to pay half of the $185,500 to Johnson and half to Eli Creekmore's estate, of which Johnson is the representative. The court previously ruled that Darren and Mary Creekmore can't receive any more from the estate.

Paul Doumit, the assistant attorney general who represented the state, said the state's agreement to the settlement is a recognition that a tragedy occurred and that the case needs to be closed.

Johnson's attorney, Jeffrey Wells, said damages were limited because state law only allows immediate family members, not grandparents, to receive damages in wrongful death cases.

So at most, he said, Eli's estate could have received Eli's lifetime earnings, minus living expenses, which Wells estimated at $271,000 if Eli had gone to college.

The two CPS employees named in the suit - Cheryl Daudt and Carol Landaas - were dismissed from the suit, also as part of the agreement.

Johnson said the money will allow her to keep speaking out for abused children. And she talked about her wish for new laws that would give grandparents more rights to protect grandchildren.

The law now doesn't give grandparents the right to participate in state actions, such as making a child a ward of the state, Johnson's attorney said.

Johnson didn't want to talk about the the events that led up to her grandson's death.

``Every child is a reminder (of Eli),'' she said before the hearing. ``Every child cry, that is like. . . .''

She couldn't finish.

Published Correction Date: 10/17/90 - The Parents Of Eli Creekmore Did Not Receive Any Money From The Estate Of The Boy. This Article Indicated The Parents Had Received Money.

--

information compiled from:

Everett Herald (Everett, Washington) 12 April 2004

Seattle Times (Seattle, Washington) - 10 Oct 1990, 04 April 1997, 29 July 1995, 18 June 2000

The Unquiet Death of Eli Creekmore. StudyMode.com. Retrieved 06, 2011, from http://www.studymode.com/essays/The-Unquiet-Death-Of-Eli-Creekmore-719629.html

Seattle PI (Seattle, Washington) 01 April 1987

New York Times (New York New York), 01 Jan 1988

Washington Vs Creekmore, 06 Nov 1989

Gonzaga University School of Law

Parents For Safe Child Care

http://www.parentsforsafechildcare.org/inremembrance.html

New York Times - Published: January 1, 1988 by Timothy Egan

Despite repeated complaints to authorities by family members and doctors, authorities placed him back with his father, which resulted in more beatings to little Matthew Eli Creekmore.

CPS had removed Eli from his home in Everett three times in two years. He was returned home each time despite evidence of continued abuse by his father. The state Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) concluded Eli's caseworkers made no major errors in the handling of this case. DSHS officials said the "system" failed Eli, and recommended changes in law and policy.

Matthew Eli's father was convicted of second degree murder and sentenced to 60 years in prison for kicking his son to death. Matthew Eli's mother was sentenced to ten years. Legislation was changed and there was an overhaul of child welfare laws as a result of the horrific case of Matthew Eli Creekmore.

--

By TIMOTHY EGAN, Special to the New York Times - Published: January 1, 1988

SEATTLE, Dec. 31, 1988 — The swollen eyes of a 3-year-old boy, bruised and battered repeatedly by his father despite intervention from state social workers, stare out from a snapshot that continues to haunt people in the Pacific Northwest.

The boy, Matthew Eli Creekmore, was kicked to death by his father, Darren Creekmore, more than a year ago. But the case is just beginning to have national repercussions as legislatures around the country study a sweeping overhaul of the child welfare laws in the State of Washington that came about as a result of the clamor over the child's death.

The rumblings of change come in the aftermath of a 200 percent increase nationally in reported cases of child abuse in the last decade, and they follow public outrage over cases like the Creekmore killing here and the fatal beating of 6-year-old Elizabeth Steinberg in Manhattan last November. An Issue of Top Priority

National experts monitoring the growing problem say that reform of child abuse laws is shaping up as a top priority for state legislatures in the coming year.

After a long trend toward keeping troubled families together, sometimes at the expense of an abused child, states like Washington are reversing previous laws and making protection of the child the paramount concern. In another change, social workers here do not have to wait for substantiated harm before removing a child from the home but can intervene on the basis of the potential risk of abuse.

This state also recently passed a pioneering law that makes child abuse resulting in death the equivalent of first-degree murder. Under this ''homicide by abuse'' law, prosecutors no longer have to prove premeditation or intent to kill to win a conviction. Instead, they must show that the abusive parent displayed ''extreme indifference to human life.''

''Premeditation in child abuse cases is almost impossible to prove,'' said State Senator Stuart Halson, who drafted the law. ''This gets us around that oft-heard defense: 'I didn't mean to kill the boy; I just wanted to discipline him.' '' Other States Study Law

The new law is being studied by a number of states, including New York, where about 100 children a year die from child abuse, according to a spokesman for the Department of Social Services. Experts estimate that nationwide from 2,000 to 5,000 children die each year as a result of abuse. Officially, there was a 23 percent increase in child abuse deaths from 1985 to 1986.

Nationally, ''there is a real crisis going on now in every state,'' said Susan Robison of the National Conference of State Legislatures, which is based in Denver. Reflecting concern about the 2.2 million abuse and neglect cases reported nationally in 1986, many states have recently enacted tightened child welfare laws. But at the same time there is a countertrend toward more legal rights for parents who are accused of abusing children.

For example, while Washington State, in its sweeping 1987 overhaul of child protection laws, gave social workers the right to interview children without notifying their parents beforehand, several members of the Colorado Legislature introduced a bill to allow parents greater legal representation in abuse investigations. That bill was voted down, but its supporters are planning to re-introduce it.

Every state now has some sort of mandatory reporting law, requiring doctors, health or day care workers who come in contact with an abused child to tell the authorities about it, but ''there is still a tremendous amount of under-reporting of abuse going on,'' said Patricia Toth, director of the National Center for the Prosecution of Child Abuse, in Alexandria, Va. Rise in Abuse Cases

Ms. Toth attributes the 200 percent increase in reported child abuse to ''a combination of increased awareness, mandatory reporting laws and perhaps a general rise in parental abuse.''

Ms. Toth said cases such as the Steinberg and Creekmore deaths ''are the catalysts for more change.''

''The country will go along, basically unaware, and then something very awful happens to grab everybody's attention,'' she said.

Deborah Daro, research director of the National Committee for the Prevention of Child Abuse, which is based in Chicago, said that after the news of Elizabeth Steinberg's death, ''There was a response like we'd never seen before, an outpouring of outrage, our phones ringing off the hook with people asking 'why,' ''

In the Washington case, social workers from the state Child Protective Services had removed the 3-year-old boy from his home in Everett three times in the 10 months before he died. But each time they returned him, despite reports from his grandmother, doctors and day-care teachers that he was being abused. His father had twice been charged with beating the boy.

At the time of the boy's death, state officials had determined that the family was making an effort to improve the situation. But on Sept. 27, 1986, the boy was kicked repeatedly in the stomach and then left to die in his bedroom. Mr. Creekmore was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to 60 years in prison, one of the most severe sentences in recent memory for such a crime. The boy's mother, Mary Creekmore, testified for the state and was allowed to plead guilty to a gross misdemeanor charge of failing to get medical attention for the child.

When the case first came to light last year, hundreds of parents demonstrated outside the social service headquarters in Everett and Olympia, the state capital, demanding that the system be overhauled. They were soon joined by Child Protective Service workers, who said inadequate financing and understaffing had contributed to what the state social service director admitted was ''a breakdown of the system.''

The case, while not unique by national standards, was an example of problems facing overburdened child welfare workers around the country. Nationally, while reported cases of child abuse rose 156 percent from 1981 to 1986, state financing to attack the problem rose a mere 2 percent, according to a recent Congressional study.

''In probably every state in the country, you've got child protection workers not going out on a lot of cases except the high priority ones, and that in itself is very dangerous,'' said Patricia Schene, director of the American Association for the Protection of Children, based in Denver.

''What's clear is that there are bad decisions being made because the system is overloaded, and that means we'll see a lot more foment in the next year or two,'' she said. A lurking problem, she said, is the dearth of foster homes. While the public and state officials are calling for more abused children to be removed from their homes, they have yet to provide adequate money to attract foster parents for those children.

In Washington, because of the fallout from the Creekmore case, more than 5,000 children were removed from their homes in the last year, but officials could only find 3,800 foster homes in which to place those children.

But increased public concern has also led to more private charity. Following the furor over young Eli's death, a new $1.3 million private center for abused children, the Eli Creekmore Memorial Center, was opened near Seattle last month.

In dedicating the center, its director, Patrick Gogerty said, ''In death, his voice became a mighty shout that stirred the conscience of all the people in the state of Washington.'

--

10/17/1990 - EVERETT - With yesterday's announcement of her $185,500 settlement with the state of Washington, Eli Creekmore's grandmother wanted to talk about the future.

`I don't have to go through specific incidents of Eli's death anymore,'' Myrna Struchen Johnson said after a hearing where the settlement was approved. ``But I can certainly go forward and try to stop what I can of the abuse of other children.''

The brief, quiet hearing in Snohomish County Superior Court was in sharp contrast to the outcry generated by Eli's death in 1986.

People across the state reacted with horror and disbelief after 3-year-old Eli was kicked to death by his father, especially because Child Protective Services employees had evidence the child had previously been abused by his father.

Darren Creekmore received a 60-year sentence for murdering his son. Mary Creekmore, Eli's mother and Johnson's daughter, pleaded guilty to failing to get her son medical attention.

The state Department of Social and Health Services concluded a flawed system failed Eli, and worked to change policies and pass new laws.

But Johnson's wrongful death lawsuit challenged that conclusion and alleged that the state and two of its employees negligently handled her grandson's case.

The state, without admitting wrongdoing, agreed to pay half of the $185,500 to Johnson and half to Eli Creekmore's estate, of which Johnson is the representative. The court previously ruled that Darren and Mary Creekmore can't receive any more from the estate.

Paul Doumit, the assistant attorney general who represented the state, said the state's agreement to the settlement is a recognition that a tragedy occurred and that the case needs to be closed.

Johnson's attorney, Jeffrey Wells, said damages were limited because state law only allows immediate family members, not grandparents, to receive damages in wrongful death cases.

So at most, he said, Eli's estate could have received Eli's lifetime earnings, minus living expenses, which Wells estimated at $271,000 if Eli had gone to college.

The two CPS employees named in the suit - Cheryl Daudt and Carol Landaas - were dismissed from the suit, also as part of the agreement.

Johnson said the money will allow her to keep speaking out for abused children. And she talked about her wish for new laws that would give grandparents more rights to protect grandchildren.

The law now doesn't give grandparents the right to participate in state actions, such as making a child a ward of the state, Johnson's attorney said.

Johnson didn't want to talk about the the events that led up to her grandson's death.

``Every child is a reminder (of Eli),'' she said before the hearing. ``Every child cry, that is like. . . .''

She couldn't finish.

Published Correction Date: 10/17/90 - The Parents Of Eli Creekmore Did Not Receive Any Money From The Estate Of The Boy. This Article Indicated The Parents Had Received Money.

--

information compiled from:

Everett Herald (Everett, Washington) 12 April 2004

Seattle Times (Seattle, Washington) - 10 Oct 1990, 04 April 1997, 29 July 1995, 18 June 2000

The Unquiet Death of Eli Creekmore. StudyMode.com. Retrieved 06, 2011, from http://www.studymode.com/essays/The-Unquiet-Death-Of-Eli-Creekmore-719629.html

Seattle PI (Seattle, Washington) 01 April 1987

New York Times (New York New York), 01 Jan 1988

Washington Vs Creekmore, 06 Nov 1989

Gonzaga University School of Law

Parents For Safe Child Care

http://www.parentsforsafechildcare.org/inremembrance.html

New York Times - Published: January 1, 1988 by Timothy Egan

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement