Married Mary Rose Rowsell, 2 Nov 1844, Barrington, Somerset, England

Children - Hyrum Glover, George Glover, Albert Glover, Emma Glover, Eliza Ann Glover, Sarah Ann Glover, Frances Alice Glover, Joseph Glover, Mary Jane Glover, Elizabeth Anna Glover

Heart Throbs of the West, Kate B. Carter, Vol. 3, p. 203

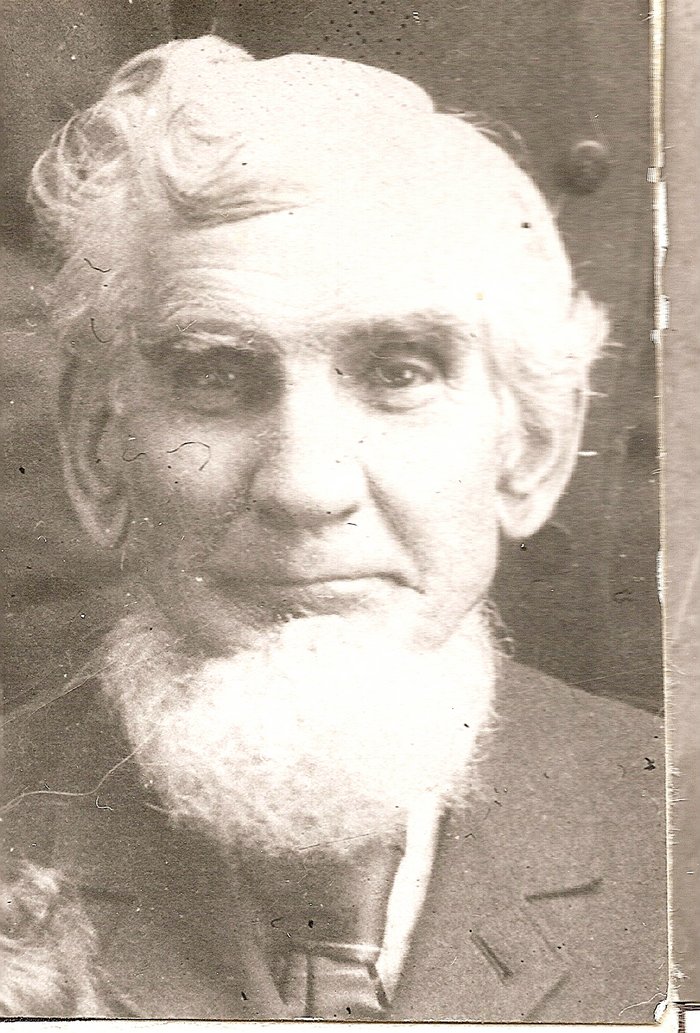

James Glover was born at Kingsbury, Episcope, Somersetshire, England, April 14, 1823. When seven years of age, he was bound as a blacksmith apprentice to John Trott, of Barrington, England. Though often mistreated, his training in this trade was very thorough. Part of his service consisted of periods of work on farms, where the apprentices were supposed to master the intricacies of farm tools and machinery, new and old. When twenty-one years of age, larger and stronger than his master, James became not only a full-fledged blacksmith but a "woodwright" as well. Soon after going into business for himself, he moved to Wales, because he could get better wages there. He remained in Wales ten years, part of that time specializing in sharpening tools for use in the coal mines. Having joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in May 1866, he, with his family, left Wales to come to America.

Landing in New York with a wife and family of nine children and only a dollar and some odd cents in his pocket, it became necessary to work for some time at his trade in order to get money with which to continue his journey. For three years he worked in a six-forge blacksmith shop in McKeesport, Pennsylvania. The following incidents indicate the character of the training he had received in England. One day a man came into the shop in McKeesport inquiring if any one could weld a six-inch shaft which had broken on their steamboat. As the vessel then lay at anchor on the river, the passengers and crew wished to avoid the delay of waiting while the shaft was sent to Pittsburgh. Receiving no reply to his first general inquiry, the owner of the ship interrogated, "Glover, couldn't you fix this up for us?" "Yes," was the reply. "If you'll give me full run of the shop and all the needed help." Using two forges, the shaft was soon repaired, the boss being so pleased that James Glover's pay was raised fifty cents a day. Later, upon reporting to his employer that he expected to leave on a certain day for Utah, the owner plead with him to remain, stating that he would lease the shop to Clover who could there make an excellent living not only for himself but for his growing boys. All entreaties fell on deaf ears.

Arriving in Salt Lake City, James Clover was informed at the old tithing office that Bishop Archibald Gardner, of West Jordan, wished a good blacksmith. Soon after James Turner met them, and with wagon and team, took the family to West Jordan.

Their shop was a cooperative affair, Alexander Beckstead furnishing the tools, Archibald Gardner the logs for the building, and the blacksmith working out his shares in the concern; the other stockholders bringing their work to be done free of charge. The shop, a small, long one, was located near the Mill Race on the south side of the Bingham Highway, just in front of and a short distance east of the present site of Hyrum Nordberg's home. Tools were few in those days, an anvil, forge, bellows, and vise being the principal ones. Iron to work with was hard to get. Many of the shoes and nails were made by hand from any old pieces of tires or iron that could be obtained. The finding of a horseshoe meant "good luck" in more than one way to the children of this household. Every small piece of iron picked up was carefully carried home to be used in the process of "making a living."

In these early days, many wild horses roamed the western range which, at the proper season, spring and summer, was covered with blue grass three or four feet high. Often these horses would be caught, supposedly tamed, and brought to the blacksmith shop to be shod. If he were not too venturesome, the smithy would tie such animals with ropes because, in the language of one who assisted in this work, "sometimes the wild blood would come back and the horse would attempt to kick the blacksmith all over the shop." The shoeing of oxen was an important part of this early-day service.

In 1870, after the burning of his place of business, James Clover moved to Midvale, where he put up a shop on his own premises. This shop, about sixteen feet by twenty feet long, was made of boards with a slab roof. The building faced the east, the large double door being just a little north of the center. Just inside the door in the southeast corner, quite a large space was reserved for shoeing horses. Here stood a couple of stout posts having iron rings attached to which the animals would be tied. In the southwest corner stood the interesting and much-used forge. Near the back of a rock platform about four feet by five feet long in a depression of about six inches, stood the fireplace. Back of the platform was the bellows, an instrument for producing a strong current of air. This machine was so formed as by being dilated and contracted to inhale air by an orifice which was opened and closed with a valve and to propel it through a tube upon the fire. This bellows had a nozzle on it about a foot long which went through the rock to the fireplace. It took an intense heat to melt the iron or metals. By means of the bellows, the amount and intensity of heat could easily be controlled. This particular bellows worked up and down. A cow's horn on the end of the long wooden handle helped to keep the hand working the bellows in place. A half barrel, always full of water which stood north of the forge, was used for cooling the tongs and other tools. The anvil set on a post driven into the ground just a short distance northeast of the forge, as well as being near the center of the shop, formed the center of attraction especially when the smith "with muscles strong as iron bands" stood near the flaming forge enveloped in the burning sparks that every stroke of his ringing hammer brought forth. In the northwestern corner of the shop reposed the long work bench, at the east end of which was the vise, a tool having two jaws closing by a lever, for holding work as in filing. The vise and anvil were those used in the original shop in West Jordan. Into the northern wall nails were driven upon which were hung horseshoes, different sized tongs, hammers, chisels, pliers, etc. The doctrine of a place for everything and everything in its place, was so well adhered to that any thing could readily be found, even in the dark.

The history of this shop would not be complete without mention of its guardian, a big black and white dog named Watch. Though near the railroad tracks where many transients or tramps were seen, children and tools were always safe in his presence. One morning, an early inquirer for a plow that he had left to be sharpened was told that he could easily get it without help as it was just under the shop door. In a few minutes the man returned to the house stating, "But, Mr. Glover, I can't get my plow. Every time I reach for it that dog pulls hard on my pant leg."

Frequent trips were made to Salt Lake City to get supplies, kegs of nails, horseshoes, fellys, spikes, etc. Then houses were few and far between. Noises could be heard for long distances. When he thought it about time for his master to return, this dog, Watch, became unusually attentive. Often time after time, he would jump to his feet, prick up his ears, and listen, only to return to his former position lying by the big door. It was interesting to note the exception. When the rattle of the right wagon was detected, he would go like a shot, never slackening his speed until he met his master a mile or a mile and a half away from home.

An occurrence which children and neighbors always looked forward to as an event of every holiday, was what was called "the firing of the anvil." The blacksmith would take the anvil off the block on which it was always placed while in use, and turn it upside down. A fuse made of black powder was placed in the hole and a plug driven in on top of it. The report made by this explosion could be heard for a long distance. On the Fourth of July, several such firecrackers were enjoyed.

All kinds of jobs were brought to the blacksmith. Often broken stove lids were repaired by putting a piece of iron under and running a rivet through the metal. Anything that could be mended had to be used again. Many tires were set in the summer, the charge being $1.00 a wheel. Plows were sharpened, new points or lays put on them. These blacksmiths were able to make everything for the plow, even the framework. When not busy with other things, James Clover made bob sleds and wagon boxes. These were often ordered months before in order to give sufficient time for their preparation. That these pioneers practiced the slogan "Live and help to live" is illustrated in the fact that when James Mills established a carpenter shop, James Glover, who lived just across the street, always sent all wooden work to his neighbor, Mr. Mills returning the favor by sending all iron work to the smith. — Mrs. Parley R. Glover.

Married Mary Rose Rowsell, 2 Nov 1844, Barrington, Somerset, England

Children - Hyrum Glover, George Glover, Albert Glover, Emma Glover, Eliza Ann Glover, Sarah Ann Glover, Frances Alice Glover, Joseph Glover, Mary Jane Glover, Elizabeth Anna Glover

Heart Throbs of the West, Kate B. Carter, Vol. 3, p. 203

James Glover was born at Kingsbury, Episcope, Somersetshire, England, April 14, 1823. When seven years of age, he was bound as a blacksmith apprentice to John Trott, of Barrington, England. Though often mistreated, his training in this trade was very thorough. Part of his service consisted of periods of work on farms, where the apprentices were supposed to master the intricacies of farm tools and machinery, new and old. When twenty-one years of age, larger and stronger than his master, James became not only a full-fledged blacksmith but a "woodwright" as well. Soon after going into business for himself, he moved to Wales, because he could get better wages there. He remained in Wales ten years, part of that time specializing in sharpening tools for use in the coal mines. Having joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in May 1866, he, with his family, left Wales to come to America.

Landing in New York with a wife and family of nine children and only a dollar and some odd cents in his pocket, it became necessary to work for some time at his trade in order to get money with which to continue his journey. For three years he worked in a six-forge blacksmith shop in McKeesport, Pennsylvania. The following incidents indicate the character of the training he had received in England. One day a man came into the shop in McKeesport inquiring if any one could weld a six-inch shaft which had broken on their steamboat. As the vessel then lay at anchor on the river, the passengers and crew wished to avoid the delay of waiting while the shaft was sent to Pittsburgh. Receiving no reply to his first general inquiry, the owner of the ship interrogated, "Glover, couldn't you fix this up for us?" "Yes," was the reply. "If you'll give me full run of the shop and all the needed help." Using two forges, the shaft was soon repaired, the boss being so pleased that James Glover's pay was raised fifty cents a day. Later, upon reporting to his employer that he expected to leave on a certain day for Utah, the owner plead with him to remain, stating that he would lease the shop to Clover who could there make an excellent living not only for himself but for his growing boys. All entreaties fell on deaf ears.

Arriving in Salt Lake City, James Clover was informed at the old tithing office that Bishop Archibald Gardner, of West Jordan, wished a good blacksmith. Soon after James Turner met them, and with wagon and team, took the family to West Jordan.

Their shop was a cooperative affair, Alexander Beckstead furnishing the tools, Archibald Gardner the logs for the building, and the blacksmith working out his shares in the concern; the other stockholders bringing their work to be done free of charge. The shop, a small, long one, was located near the Mill Race on the south side of the Bingham Highway, just in front of and a short distance east of the present site of Hyrum Nordberg's home. Tools were few in those days, an anvil, forge, bellows, and vise being the principal ones. Iron to work with was hard to get. Many of the shoes and nails were made by hand from any old pieces of tires or iron that could be obtained. The finding of a horseshoe meant "good luck" in more than one way to the children of this household. Every small piece of iron picked up was carefully carried home to be used in the process of "making a living."

In these early days, many wild horses roamed the western range which, at the proper season, spring and summer, was covered with blue grass three or four feet high. Often these horses would be caught, supposedly tamed, and brought to the blacksmith shop to be shod. If he were not too venturesome, the smithy would tie such animals with ropes because, in the language of one who assisted in this work, "sometimes the wild blood would come back and the horse would attempt to kick the blacksmith all over the shop." The shoeing of oxen was an important part of this early-day service.

In 1870, after the burning of his place of business, James Clover moved to Midvale, where he put up a shop on his own premises. This shop, about sixteen feet by twenty feet long, was made of boards with a slab roof. The building faced the east, the large double door being just a little north of the center. Just inside the door in the southeast corner, quite a large space was reserved for shoeing horses. Here stood a couple of stout posts having iron rings attached to which the animals would be tied. In the southwest corner stood the interesting and much-used forge. Near the back of a rock platform about four feet by five feet long in a depression of about six inches, stood the fireplace. Back of the platform was the bellows, an instrument for producing a strong current of air. This machine was so formed as by being dilated and contracted to inhale air by an orifice which was opened and closed with a valve and to propel it through a tube upon the fire. This bellows had a nozzle on it about a foot long which went through the rock to the fireplace. It took an intense heat to melt the iron or metals. By means of the bellows, the amount and intensity of heat could easily be controlled. This particular bellows worked up and down. A cow's horn on the end of the long wooden handle helped to keep the hand working the bellows in place. A half barrel, always full of water which stood north of the forge, was used for cooling the tongs and other tools. The anvil set on a post driven into the ground just a short distance northeast of the forge, as well as being near the center of the shop, formed the center of attraction especially when the smith "with muscles strong as iron bands" stood near the flaming forge enveloped in the burning sparks that every stroke of his ringing hammer brought forth. In the northwestern corner of the shop reposed the long work bench, at the east end of which was the vise, a tool having two jaws closing by a lever, for holding work as in filing. The vise and anvil were those used in the original shop in West Jordan. Into the northern wall nails were driven upon which were hung horseshoes, different sized tongs, hammers, chisels, pliers, etc. The doctrine of a place for everything and everything in its place, was so well adhered to that any thing could readily be found, even in the dark.

The history of this shop would not be complete without mention of its guardian, a big black and white dog named Watch. Though near the railroad tracks where many transients or tramps were seen, children and tools were always safe in his presence. One morning, an early inquirer for a plow that he had left to be sharpened was told that he could easily get it without help as it was just under the shop door. In a few minutes the man returned to the house stating, "But, Mr. Glover, I can't get my plow. Every time I reach for it that dog pulls hard on my pant leg."

Frequent trips were made to Salt Lake City to get supplies, kegs of nails, horseshoes, fellys, spikes, etc. Then houses were few and far between. Noises could be heard for long distances. When he thought it about time for his master to return, this dog, Watch, became unusually attentive. Often time after time, he would jump to his feet, prick up his ears, and listen, only to return to his former position lying by the big door. It was interesting to note the exception. When the rattle of the right wagon was detected, he would go like a shot, never slackening his speed until he met his master a mile or a mile and a half away from home.

An occurrence which children and neighbors always looked forward to as an event of every holiday, was what was called "the firing of the anvil." The blacksmith would take the anvil off the block on which it was always placed while in use, and turn it upside down. A fuse made of black powder was placed in the hole and a plug driven in on top of it. The report made by this explosion could be heard for a long distance. On the Fourth of July, several such firecrackers were enjoyed.

All kinds of jobs were brought to the blacksmith. Often broken stove lids were repaired by putting a piece of iron under and running a rivet through the metal. Anything that could be mended had to be used again. Many tires were set in the summer, the charge being $1.00 a wheel. Plows were sharpened, new points or lays put on them. These blacksmiths were able to make everything for the plow, even the framework. When not busy with other things, James Clover made bob sleds and wagon boxes. These were often ordered months before in order to give sufficient time for their preparation. That these pioneers practiced the slogan "Live and help to live" is illustrated in the fact that when James Mills established a carpenter shop, James Glover, who lived just across the street, always sent all wooden work to his neighbor, Mr. Mills returning the favor by sending all iron work to the smith. — Mrs. Parley R. Glover.

Family Members

-

![]()

George Glover

1846–1917

-

![]()

Sarah Ann Glover Cundick

1849–1921

-

![]()

Albert Glover Sr

1852–1925

-

![]()

Joseph Glover

1854–1937

-

![]()

Mary Jane Glover Amundsen

1857–1937

-

Hyrum Glover

1859–1874

-

![]()

Elizabeth Glover Amundsen

1861–1928

-

![]()

Emma Glover Brown

1864–1881

-

![]()

Eliza Ann Glover Mounteer

1866–1937

-

![]()

Frances Alice Glover Bateman

1868–1960

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

Advertisement