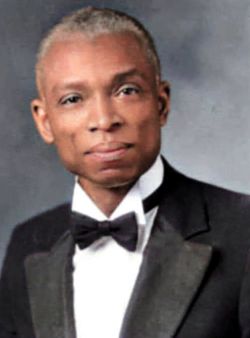

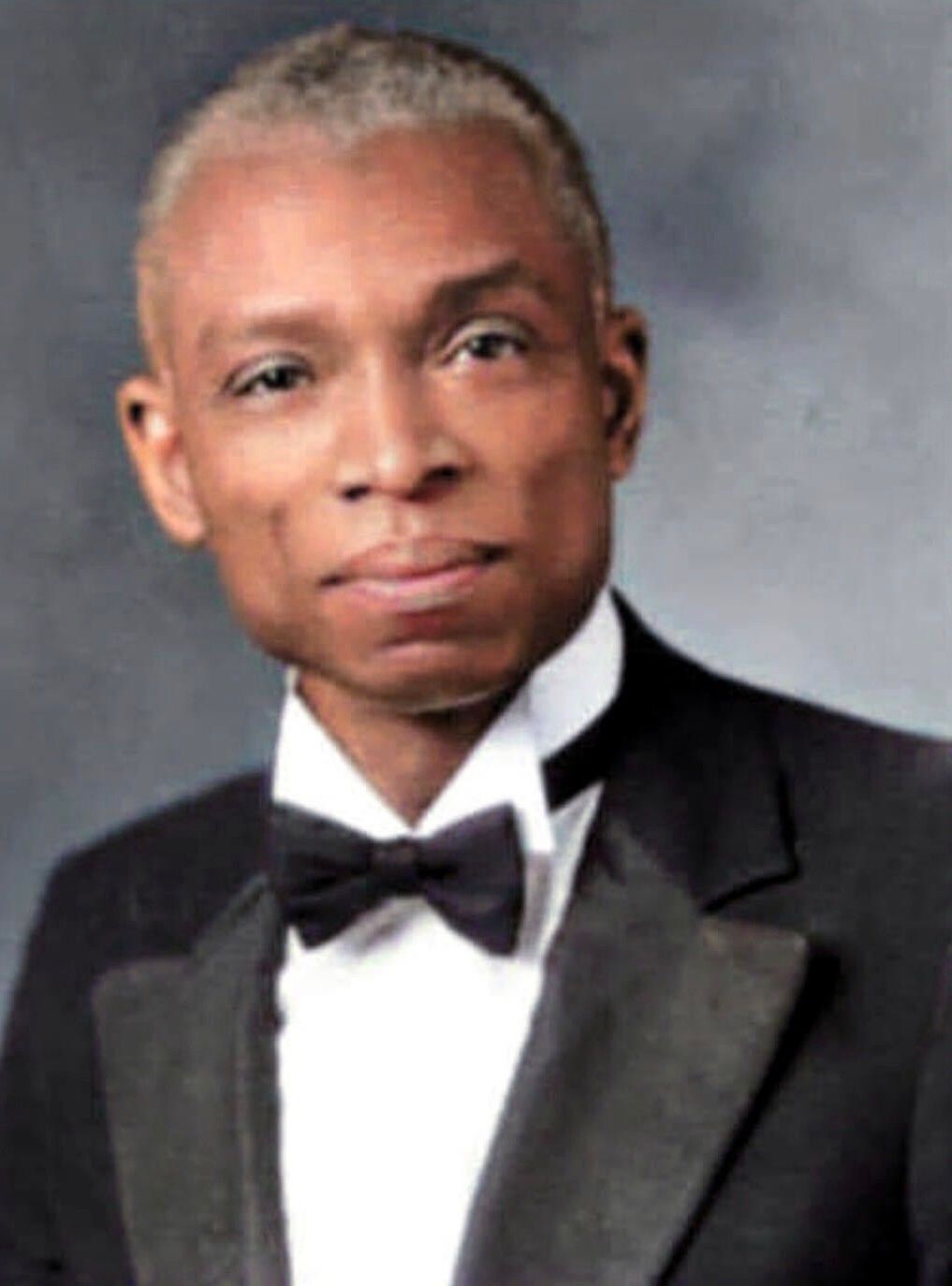

John Morton-Finney was born on June 25, 1889 in Uniontown, Kentucky. He was the son of a slave whose ancestors migrated from Ethiopia to Nigeria. He grew up in a family of seven children where poetry readings and political debates were evening activities. His mother died when he was 14, so his father sent the children to live on their grandfather's farm in Missouri. Morton-Finney served in the 24th U.S. Infantry Regiment from 1911 to 1914 and went to the Philippines. He rose to the rank of sergeant and applied for an officer's commission. In 1913, his commander told him that, although he had the intelligence and the education to be an officer, he was disqualified due to his race. When the commander said that he wouldn't be able to go to the officers' club, Morton-Finney responded that he didn't want to go to the officers' club; he wanted to be an officer. Trooper Morton-Finney received an honorable discharge and then, earned his first college degree from Lincoln College in Missouri. He began teaching in a one-room schoolhouse, but when World War I broke out, he returned to the military as a Buffalo Soldier. He served in France in the American Expeditionary Force and saw much destruction: survivors of mustard gas, men spitting up parts of their lungs, and the graves of 30,000 Frenchmen. After the war, he earned degrees in math, French, and history. At Lincoln College, he heard about a new French teacher, Pauline Ray, with a degree from Cornell University. Morton-Finney signed into her class and won her heart. They were married and moved to Indianapolis in 1922. THey had six children. He taught junior high math and social studies at Indianapolis Public Schools, where he also served as principal. In 1927, he was hired as one of the first teachers at all-black Crispus Attucks High School (CAHS). He served as head of the foreign language department. His Students learned life skills such as how to set goals, plan their futures, and take responsibility for their actions. They learned that racism is an unacceptable excuse for failure and developed a deep respect for their history and culture. During World War II, he was cited for directing the rationing tickets program for African Americans in Indianapolis. Various merchandise such as meats, sugar, butter, gasoline, and rubber were strictly rationed. Many items were especially scarce, but rationing guaranteed that everyone received equal amounts of raw materials. John Morton-Finney's love for learning remained constant. In 1935, he earned his first law of five law degrees. During his life, he read three or four books at a time. Twenty books would be stacked beside his bed with five sharpened pencils, and the television turned to the news. During an interview on his 100th birthday. Morton-Finney said, "I can get interested in so many things. There is so much to know in the world. And it is such a pleasure for me to learn. Besides, a cultivated man would never say - I finished my education - because he graduated from college. There is no end to learning." He credited his grandfather with giving him advice that served him well. He believed that moderation in all matters is the key to a long life. Altogether, he earned 12 degrees. He practiced law until he was 106 and died on January 28, 1998, at the age of 108. At the time of his death, he was the last surviving member of the Buffalo Soldiers and the oldest veteran in the state of Indiana. He received a full honor military memorial service and was laid to rest at Crown Hill Cemetery.

John Morton-Finney was born on June 25, 1889 in Uniontown, Kentucky. He was the son of a slave whose ancestors migrated from Ethiopia to Nigeria. He grew up in a family of seven children where poetry readings and political debates were evening activities. His mother died when he was 14, so his father sent the children to live on their grandfather's farm in Missouri. Morton-Finney served in the 24th U.S. Infantry Regiment from 1911 to 1914 and went to the Philippines. He rose to the rank of sergeant and applied for an officer's commission. In 1913, his commander told him that, although he had the intelligence and the education to be an officer, he was disqualified due to his race. When the commander said that he wouldn't be able to go to the officers' club, Morton-Finney responded that he didn't want to go to the officers' club; he wanted to be an officer. Trooper Morton-Finney received an honorable discharge and then, earned his first college degree from Lincoln College in Missouri. He began teaching in a one-room schoolhouse, but when World War I broke out, he returned to the military as a Buffalo Soldier. He served in France in the American Expeditionary Force and saw much destruction: survivors of mustard gas, men spitting up parts of their lungs, and the graves of 30,000 Frenchmen. After the war, he earned degrees in math, French, and history. At Lincoln College, he heard about a new French teacher, Pauline Ray, with a degree from Cornell University. Morton-Finney signed into her class and won her heart. They were married and moved to Indianapolis in 1922. THey had six children. He taught junior high math and social studies at Indianapolis Public Schools, where he also served as principal. In 1927, he was hired as one of the first teachers at all-black Crispus Attucks High School (CAHS). He served as head of the foreign language department. His Students learned life skills such as how to set goals, plan their futures, and take responsibility for their actions. They learned that racism is an unacceptable excuse for failure and developed a deep respect for their history and culture. During World War II, he was cited for directing the rationing tickets program for African Americans in Indianapolis. Various merchandise such as meats, sugar, butter, gasoline, and rubber were strictly rationed. Many items were especially scarce, but rationing guaranteed that everyone received equal amounts of raw materials. John Morton-Finney's love for learning remained constant. In 1935, he earned his first law of five law degrees. During his life, he read three or four books at a time. Twenty books would be stacked beside his bed with five sharpened pencils, and the television turned to the news. During an interview on his 100th birthday. Morton-Finney said, "I can get interested in so many things. There is so much to know in the world. And it is such a pleasure for me to learn. Besides, a cultivated man would never say - I finished my education - because he graduated from college. There is no end to learning." He credited his grandfather with giving him advice that served him well. He believed that moderation in all matters is the key to a long life. Altogether, he earned 12 degrees. He practiced law until he was 106 and died on January 28, 1998, at the age of 108. At the time of his death, he was the last surviving member of the Buffalo Soldiers and the oldest veteran in the state of Indiana. He received a full honor military memorial service and was laid to rest at Crown Hill Cemetery.

Bio by: Find a Grave

Family Members

Advertisement

See more Morton-Finney memorials in:

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement