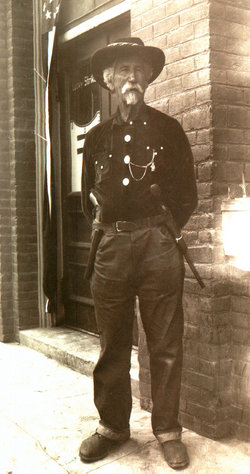

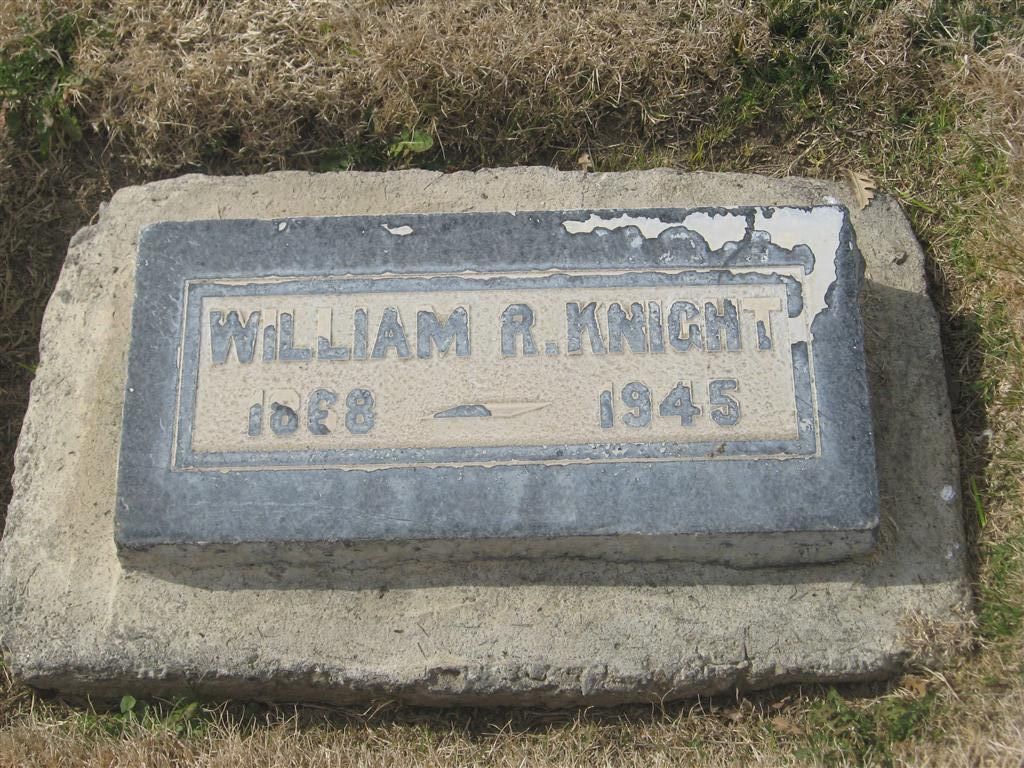

William Riley Knight, 78 year old pioneer resident of Los Banos, died last Friday at the home of his sister, Mrs. John Wesling, at Tipton, Solana county. Born at Tres Pinos, he came to this community with his parents when six years old and resided here, almost continuously until last July when he suffered a slight paralytic stroke at his ranch home four miles west of town, and was taken to the home of his nephew, Cecil Knight, at Newman, where he remained for a month before going to join his sister at Tipton. Funeral services were conducted at the Los Banos Methodist church Wednesday after noon at two o'clock, with Rev. Charles P. Martin officiating. Burial was made in the Los Banos cemetery. Mr. Knight is survived by his sister, Mrs. Wesling; another sister, Mrs. Martha Petee, of Oroville; and a brother, John Knight. The story of Mr. Knight's life in this community is a long record of firsts. In his early youth he and his father hunted antelope over most of this valley, and he was one of the first market hunters, using a 27-lb., No. 4 gauge shotgun imported from England. He has stated that he shipped the first sack of game from the Los Banos depot, which was consigned to A. P. Giannini, now president of the Bank of America. Soon after the town of Los Banos was founded he opened a gun shop here, which immediately prospered, and later the shop was expanded to include a bicycle shop. He was an expert gunsmith, and not only repaired the expensive English guns used by the market hunters, but also manufactured guns of his own make, of which there are still several specimens in state museums. Mr. Knight and his father built the first house to be constructed in Los Banos, a small cottage which is still standing in the 600 block on J street. The houses which then comprised the new settlement of Los Banos had been moved in from the plains. He also brought into this community and operated the first combine harvester, in the year 1893. Before then, stationary threshing machines were used to harvest the grain. Mr. Knight also owned the first automobile in Los Banos, a one cylinder Oldsmobile. He later sold this machine to Mace Roberts and purchased a newer model Oldsmobile. In 1904 he made a trip in this second car to Los Angels. The trip south required almost three weeks, due to numerous breakdowns. In Los Angeles, the car so frightened the dray teams that he was forced to leave it in a livery stable during most of his stay there.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

"A Market Hunter Who Went Places"

By Ralph L. Milliken, Curator, The Milliken Museum, Los Banos, California.

Bill Knight was an outstanding man in the Los Banos of pioneer days. Although he made his living as a struggling market hunter he was always ready to tackle anything new that promised adventure. In his older days he boasted that had it not been for himself and like him the automobile when it first came on the market would never have gotten off the ground so quickly. "It would have been years before the American public would have accepted it," he maintained.

Most people, when automobiles first came on sale, were afraid of them. "You'll never get me to ride in one of them things" was the common expression. A few people even held them in contempt. Henry Miller, the Cattle King, called the automobile the "Devil's Invention," and predicted the it would never amount to anything while there were so many good horses in California. But with Bill Knight things were different. As soon as he saw his first automobile he determined that he was going to own one.

When Bill was just a boy he was already making his own living running a string of traps on the Kings River about fifteen miles south of Fresno. He was trapping for beaver, coons and otter, although these pelts were not worth much then. Beavers brought three or four dollars each. Coonskins were two bits apiece. Otters brought from a dollar and a half to six dollars. It was down around Centerville that he was trapping. The river bottom was still in its wild state and was full of blackberry vines and Indians.

Bill used to go at night and peer over the cliff to watch the Indians in their camp. Under the bluff he could see forty or fifty campfires burning and the squaws cooking. The main roasting was done on the larger fires but each squaw had her own little fire of a few sticks burning in the darkness, there were at least a couple of hundred Indians in the camp. Many had come recently from the mountains to fish and pick blackberries. A dozen or more were employed shearing sheep for a man named Straud. Some few of the Indians picked berries and packed them on foot to Fresno fifteen miles away where they sold them.

In order to make a little spare money for himself Bill worked for a short time for this sheep man, John Straud. This man lived in a brick house that had been built in the early days. It had iron doors and windows for protection. It was a very old house. Just under the bluff below Straud's house was the Indian camp.

Bill's job was to run sheep into a corral and from there into the shearing pens. As the sheep went out of the jump after being shorn Bill would mark them with a dab of coal tar.

But Bill didn't have much to do. The Indians got five cents apiece for each sheep they sheared. Although they were good sheep shearer's they never made much money. The bucks would shear only about five sheep a day. This would give them all the money they wanted for the time being. The squaws would do better. They would shear twelve or fifteen.

About every other night Mr. Staud would have Bill drive out a weather for the Indians to feed on. They would eat every bit of the sheep but the pelt and the bones. "Don't you ever think," Bill used to say, "that Indians went hungry. They were well fed and all were fat."

Bill matured into a tall, muscular young man who didn't need a gun to hold his own in any crowd. He always aimed to be where his services and skills were most in demand. When market hunting at Los Banos in summertime was at a low ebb he would go over to the Salinas Valley and work on harvesting outfits for a few months. Here he learned to run the steam engines that powered the grain separators of the era. With the return of the geese and ducks in the fall from the north and market hunting was again profitable he was back again on the San Joaquin River. One return trip he tried out a brilliant idea of his. He thought that by walking home he could both save money and be making money. He set out boldly towards the mountains. He expected to reach Old Los Banos by nightfall.

Bill came by way of Los Muertos. Towards noon he came in sight of a cabin that he knew by reason of its neat appearance and well-swept yard must be the home of a Spanish family. Bill stopped to ask for a drink of water. He found that an old Mexican was living there all alone. The old man just killed a goat. When the man found that Bill's had been a good friend of his father nothing would do but Bill must stay and have dinner with him. Bill soon discovered from the plentiful supply of venison on hand that this Mexican was quite a hunter himself. For a couple of (?) the two hunters feasted and visited, toasting their fathers and their grandfathers - far too long a time if Bill was to reach Old Los Banos before dark.

Bill finally trudged on with his bag of sandwiches intact. At dark he was becoming desperate. He was thirsty. His feet were sore. He was hungry. Unexpectedly, long after sundown, he came to a sheepherder's cabin tucked away in the hills. He knew that in the middle of the summer the cabin would be vacant. Bill hollered. There was no answer. But he knew there would be a spring of water near the cabin. Else the cabin would never have been built here.

The cabin door consisted of three boards and was nailed shut. But that didn't worry Bill. With one kick of his heavy boot he knock the middle board in. Going inside the only thing he could find was a woolsack stuffed with straw on a bunk built along side of the wall.

Bill went outside and started looking for water. A long unused path led to a nice little spring. He drank copiously. He pulled off his boots and cooled his burning feet. He broke open his bag of sandwiches. Going back in the cabin he sprawled himself out comfortable on the woolsack.

Everything in the darkness was dead silent; suddenly he felt a snake begin to wriggle in the straw beneath him. Bill sat bolt upright, he jumped up and with his boot began pounding the woolsack unmercifully, he would alternately beat the woolsack and then lay down to try and get some sleep. Sometime during the night a rat or a mouse sampled Bill's big toe! Sleep never came to Bill all night long.

At daylight, after the longest he had ever spent, he was up and out and on his way to Old Los Banos. He had sadly come to the conclusion that sometimes saving comes at too great a price. His battle with the snake was the only battle Bill ever lost.

Bill Knight was also known a Buffalo Bill. He and Bill Cody were dead ringers of each other. For several seasons Bill was the stand-in for Cody whenever Buffalo Bill didn't care to lead his circus parade in person. Bill toured Europe and all over America. One of the spectacular stunts of the Wild West Shows circus parade was the shooting of glass balls tossed up at intervals along the march. These balls would be shot into a thousand pieces by the leader of the parade with unerring certainty. Spectators watching the parade would go home and tell their friends what a dead shot Buffalo Bill was. "He never missed a shot!" The secret told around Los Banos was that both of the trigger happy Bills used bird shot in their rifles. To miss was an impossibility.

When Bill Knight brought home a circus rider as his wife and returned to market hunting "Horseless carriages" were just beginning to appear occasionally on the wagon roads of California. Bill happened to be in town when one of these came pioneering through Los Banos. Bill immediately pictured himself a perch one of these power buggies. He took the train for San Francisco. He soon discovered there were only four or five automobiles owned in the city and that there were no agencies where he could buy one. But the Pioneer Automobile Company was taking orders for cars to be shipped out from the East. Bill planked down Seven Hundred Dollars. His order was number Twenty-Two, when the carload came his car would be unloaded for him in Fresno.

Some weeks later Bill was right on hand in Fresno when his car arrived. It was the twenty-second Oldsmobile in California. It was more like a buggy than a modern automobile. Although it had a dashboard it had no windshield, nor was there a steering wheel, instead there was a tiller that lay across the lap of the driver. To get into the drivers seat this iron bar had to be raised. The wheels had wooden spokes and rubber tires. The outside tires were simply canvas, covered over with a little rubber. The inside tubes were rubber. The car had a chain drive. The engine was high up back of the driver's seat. It was one cylinder and was four and a half horsepower. The crankcase was on the right hand side of the car. The gasoline tank held four gallons of gasoline. There was a water tank beside the engine and a couple of coils down under the driver's feet. The water in the tank at the engine would circulate from the engine down through the coils and then back up to the tank. There was no generator or magneto and the car used dry cell batteries. But the car made thirty miles on a gallon of gas.

Because Bill knew how to run a steam engine he had no difficulty in coaxing his new found toy to behave properly the seventy miles from Fresno to Los Banos.

Bill had bought the automobile thinking to use it in hunting ducks. But soon he was running "Firsts" in every direction. He was the first to hunt quail with an automobile. He was the first to reach Mercy Springs in an automobile. He was the first from Los Banos to visit the Pinnacles south of Hollister. Soon Bill became really venturesome, he decided on a trip to Los Angeles!

It took Bill only three or four days to reach Los Angeles. He went by way of Fresno. The first night he stayed at a Mexican ranch down near Bakersfield. The only person in sight when he drove up was a little Spanish boy. He was completely carried away watching this strange buggy. Bill asked him if he thought his folks would let him stay over night. "I dunno." The boy's sole interest was in looking at Bill's automobile. Presently the boy's mother came to the door. "Yes" he could put his buggy in the barn and stay all night. When an older brother returned home after dark nothing would do but the little brother should light the lantern and take his brother out to the barn and show the surprise the little brother had for him, - a buggy with no horse to pull it. The next morning when Bill was ready to leave. "No, Senor. Our home is your home".

From Bakersfield on towards the mountains to the south the road was terrible. Freight wagons had worn ruts so deep that the axles of the wagons in many places dragged on the ground. Bill had to drive for miles astride these ruts. If he had ever gotten his wheels into one of these ditches he would never have been able to get it out alone. He went by way of Gorham Station and then by Elizabeth Lake, continuing on to Newhall Pass.

Bill was coming down a grade and noticed ahead of him a man driving out of a ranch onto the road. Bill supposed of course that the man would stop until he got down the grade. Instead the man kept right on coming. They met on the grade. Bill pulled to one side hoping the man would be able to pass. Instead his horse tried to turn around in the shafts and refused to come anywhere near Bill's "buggy". The Irishman was furious. He called Bill every name his Irish tongue could muster. Getting out of his buggy he went around back to the boot and took out a long blacksmith's hammer. Bill quickly sensed that the fellow was intending to smash the automobile to pieces. Like all good market hunters Bill always carried his "gat" where he could hold of it handy. His revolver was lying on the automobile seat right beside him. He picked it up and drew a dead bead on the Irishman's head. "Don't try anything like that!" ordered Bill. The battle was over before it began. Bill edged his automobile around the stranded buggy and coasted along down the grade.

Never in his life did so many people in so many languages curse Bill as when he plowed boldly down the main street of Los Angeles. Pandemonium had broken loose. The thoroughfare was filled with horses - carriages - dray teams - horse drawn streetcars. Every horse tried to climb a telephone pole. Every driver was hollering "Whoa" and at the same time cursing Bill at the top of their voice. "Get that contraption out of town!"

Bill was afraid to stop. He kept right on going, he arrived at the other side of Los Angeles. He saw a livery barn, driving up he asked the proprietor if he could park his automobile for a few days in his livery barn. The astonished man, seeing the determined look on Bill's face, meekly answered, "Yes."

A few days later when Bill was ready to start back to Los Banos he knew enough to come around the side of Los Angeles. He got up early in the morning to miss as many horses as possible. He came by way of what is now Hollywood. There was no Hollywood there then. A Soldiers Home stood on a high bluff. Bill wanted to come home by way of the coast. He overtook a Mexican traveling on foot. Bill savvied better than to ask him how to get to San Francisco. That would be much to ask of a man traveling on foot. He asked the man how to get to Santa Barbara. "You follow this road until you come to Pico's Ranch. Then you ask them the road to Castro's hacienda. Then you go on for quite a bit until you come to the Calabazas Ranch. From there keep asking until you come to Santa Barbara."

In going down a grade on the Canejo Pass on his way to Santa Barbara the car got to running faster and faster. The ocean was on Bill's left about fifty feet down. At a turn in the road a short distance ahead he could see that he was going to go over the cliff. There was a big, tall tree on his right. He headed the car right up the trunk. Bill landed on his feet. In taking stock Bill found that the radiator leaked a little, the front axle was bent a trifle. But his leather brakes were worn nearly to ribbons.

In Santa Barbara a garage was unheard of and machine shops were non-existent. Inquiring around Bill found that an old man was fitting up his boy with a future repair shop. The father evidently could foresee that automobiles were going to be the coming thing and sensed that machine shops would be needed to keep them running.

Bill located the young man's shop. Evidently some machine company had rigged up the place for the boy. All the machines, lathes and welding tools were new and first class. The young man told Bill that he didn't know yet how to run the machinery. Bill explained that would make no difference, that he could make the repairs of on the car if he could use the machinery. Bill stayed two or three days turning out brake drums and new brakes for his car. The boy was so delighted with what Bill taught him about machinery that he would take nothing for the use of his shop.

Bill was almost home; he was within five mile of San Jaun Batista. There was a little bridge over an inviting stream. Bill decided to get some water for his leaking radiator. When Bill cranked up the engine again and climbed back in the seat the car stood stock-still. Bill realized that his journey was ended. He knew that the crankshaft was broken.

Bill walked to San Juan Bautista where he hired a drayman to come with a couple of planks and haul the automobile into town. Together they ran the helpless machine up on the planks onto the back end of the dray and hauled it to a blacksmith's shop in San Juan. An old French locksmith had running the shop for years. The Frenchman was flabbergasted, to think that he was qualified to work on an automobile! For him to repair such complicated machinery. "Impossible!"

Bill assured the old man that if he would let him have the use of his "fire" and some of his tools he believed that he could fix the crankshaft himself. The old man looked on in amazement as Bill worked. Bill drilled three holes through the broken crankshaft. Then he looked around the shop for some steel teeth from and old hay rake. He cut off three pieces of about four inches, straightened them and filed them to fit the holes he had bored. The chalked the broken shaft and lined up the two parts as true as he possibly could. He drilled three holes in the broken part. With a sledgehammer he pounded the two parts together. "Well, I take my hat off to you," declared the old blacksmith.

Bill was three weeks on his trip to Los Angeles. In all that time he saw nary an automobile on the road. Whenever Bill would stop in a town even just to get a drink of water, the crowd that would gather would be so dense that he could hardly get back to his machine.

Bill came home by way of Pacheco Pass. It was then but a wagon road. When he got to Los Banos his car was running better than ever. He had already ordered new parts in San Francisco. They arrived from the east weeks later. "Do you know," chuckled Bill Gleefully "I never did put in those new parts!"?

Anybody could fix one... People got up their courage and soon everybody was riding in Automobiles."

Source: ENTERPRISE, Los Banos, Cal., Thursday, October 1, 1970, Section A-7

William Riley Knight, 78 year old pioneer resident of Los Banos, died last Friday at the home of his sister, Mrs. John Wesling, at Tipton, Solana county. Born at Tres Pinos, he came to this community with his parents when six years old and resided here, almost continuously until last July when he suffered a slight paralytic stroke at his ranch home four miles west of town, and was taken to the home of his nephew, Cecil Knight, at Newman, where he remained for a month before going to join his sister at Tipton. Funeral services were conducted at the Los Banos Methodist church Wednesday after noon at two o'clock, with Rev. Charles P. Martin officiating. Burial was made in the Los Banos cemetery. Mr. Knight is survived by his sister, Mrs. Wesling; another sister, Mrs. Martha Petee, of Oroville; and a brother, John Knight. The story of Mr. Knight's life in this community is a long record of firsts. In his early youth he and his father hunted antelope over most of this valley, and he was one of the first market hunters, using a 27-lb., No. 4 gauge shotgun imported from England. He has stated that he shipped the first sack of game from the Los Banos depot, which was consigned to A. P. Giannini, now president of the Bank of America. Soon after the town of Los Banos was founded he opened a gun shop here, which immediately prospered, and later the shop was expanded to include a bicycle shop. He was an expert gunsmith, and not only repaired the expensive English guns used by the market hunters, but also manufactured guns of his own make, of which there are still several specimens in state museums. Mr. Knight and his father built the first house to be constructed in Los Banos, a small cottage which is still standing in the 600 block on J street. The houses which then comprised the new settlement of Los Banos had been moved in from the plains. He also brought into this community and operated the first combine harvester, in the year 1893. Before then, stationary threshing machines were used to harvest the grain. Mr. Knight also owned the first automobile in Los Banos, a one cylinder Oldsmobile. He later sold this machine to Mace Roberts and purchased a newer model Oldsmobile. In 1904 he made a trip in this second car to Los Angels. The trip south required almost three weeks, due to numerous breakdowns. In Los Angeles, the car so frightened the dray teams that he was forced to leave it in a livery stable during most of his stay there.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

"A Market Hunter Who Went Places"

By Ralph L. Milliken, Curator, The Milliken Museum, Los Banos, California.

Bill Knight was an outstanding man in the Los Banos of pioneer days. Although he made his living as a struggling market hunter he was always ready to tackle anything new that promised adventure. In his older days he boasted that had it not been for himself and like him the automobile when it first came on the market would never have gotten off the ground so quickly. "It would have been years before the American public would have accepted it," he maintained.

Most people, when automobiles first came on sale, were afraid of them. "You'll never get me to ride in one of them things" was the common expression. A few people even held them in contempt. Henry Miller, the Cattle King, called the automobile the "Devil's Invention," and predicted the it would never amount to anything while there were so many good horses in California. But with Bill Knight things were different. As soon as he saw his first automobile he determined that he was going to own one.

When Bill was just a boy he was already making his own living running a string of traps on the Kings River about fifteen miles south of Fresno. He was trapping for beaver, coons and otter, although these pelts were not worth much then. Beavers brought three or four dollars each. Coonskins were two bits apiece. Otters brought from a dollar and a half to six dollars. It was down around Centerville that he was trapping. The river bottom was still in its wild state and was full of blackberry vines and Indians.

Bill used to go at night and peer over the cliff to watch the Indians in their camp. Under the bluff he could see forty or fifty campfires burning and the squaws cooking. The main roasting was done on the larger fires but each squaw had her own little fire of a few sticks burning in the darkness, there were at least a couple of hundred Indians in the camp. Many had come recently from the mountains to fish and pick blackberries. A dozen or more were employed shearing sheep for a man named Straud. Some few of the Indians picked berries and packed them on foot to Fresno fifteen miles away where they sold them.

In order to make a little spare money for himself Bill worked for a short time for this sheep man, John Straud. This man lived in a brick house that had been built in the early days. It had iron doors and windows for protection. It was a very old house. Just under the bluff below Straud's house was the Indian camp.

Bill's job was to run sheep into a corral and from there into the shearing pens. As the sheep went out of the jump after being shorn Bill would mark them with a dab of coal tar.

But Bill didn't have much to do. The Indians got five cents apiece for each sheep they sheared. Although they were good sheep shearer's they never made much money. The bucks would shear only about five sheep a day. This would give them all the money they wanted for the time being. The squaws would do better. They would shear twelve or fifteen.

About every other night Mr. Staud would have Bill drive out a weather for the Indians to feed on. They would eat every bit of the sheep but the pelt and the bones. "Don't you ever think," Bill used to say, "that Indians went hungry. They were well fed and all were fat."

Bill matured into a tall, muscular young man who didn't need a gun to hold his own in any crowd. He always aimed to be where his services and skills were most in demand. When market hunting at Los Banos in summertime was at a low ebb he would go over to the Salinas Valley and work on harvesting outfits for a few months. Here he learned to run the steam engines that powered the grain separators of the era. With the return of the geese and ducks in the fall from the north and market hunting was again profitable he was back again on the San Joaquin River. One return trip he tried out a brilliant idea of his. He thought that by walking home he could both save money and be making money. He set out boldly towards the mountains. He expected to reach Old Los Banos by nightfall.

Bill came by way of Los Muertos. Towards noon he came in sight of a cabin that he knew by reason of its neat appearance and well-swept yard must be the home of a Spanish family. Bill stopped to ask for a drink of water. He found that an old Mexican was living there all alone. The old man just killed a goat. When the man found that Bill's had been a good friend of his father nothing would do but Bill must stay and have dinner with him. Bill soon discovered from the plentiful supply of venison on hand that this Mexican was quite a hunter himself. For a couple of (?) the two hunters feasted and visited, toasting their fathers and their grandfathers - far too long a time if Bill was to reach Old Los Banos before dark.

Bill finally trudged on with his bag of sandwiches intact. At dark he was becoming desperate. He was thirsty. His feet were sore. He was hungry. Unexpectedly, long after sundown, he came to a sheepherder's cabin tucked away in the hills. He knew that in the middle of the summer the cabin would be vacant. Bill hollered. There was no answer. But he knew there would be a spring of water near the cabin. Else the cabin would never have been built here.

The cabin door consisted of three boards and was nailed shut. But that didn't worry Bill. With one kick of his heavy boot he knock the middle board in. Going inside the only thing he could find was a woolsack stuffed with straw on a bunk built along side of the wall.

Bill went outside and started looking for water. A long unused path led to a nice little spring. He drank copiously. He pulled off his boots and cooled his burning feet. He broke open his bag of sandwiches. Going back in the cabin he sprawled himself out comfortable on the woolsack.

Everything in the darkness was dead silent; suddenly he felt a snake begin to wriggle in the straw beneath him. Bill sat bolt upright, he jumped up and with his boot began pounding the woolsack unmercifully, he would alternately beat the woolsack and then lay down to try and get some sleep. Sometime during the night a rat or a mouse sampled Bill's big toe! Sleep never came to Bill all night long.

At daylight, after the longest he had ever spent, he was up and out and on his way to Old Los Banos. He had sadly come to the conclusion that sometimes saving comes at too great a price. His battle with the snake was the only battle Bill ever lost.

Bill Knight was also known a Buffalo Bill. He and Bill Cody were dead ringers of each other. For several seasons Bill was the stand-in for Cody whenever Buffalo Bill didn't care to lead his circus parade in person. Bill toured Europe and all over America. One of the spectacular stunts of the Wild West Shows circus parade was the shooting of glass balls tossed up at intervals along the march. These balls would be shot into a thousand pieces by the leader of the parade with unerring certainty. Spectators watching the parade would go home and tell their friends what a dead shot Buffalo Bill was. "He never missed a shot!" The secret told around Los Banos was that both of the trigger happy Bills used bird shot in their rifles. To miss was an impossibility.

When Bill Knight brought home a circus rider as his wife and returned to market hunting "Horseless carriages" were just beginning to appear occasionally on the wagon roads of California. Bill happened to be in town when one of these came pioneering through Los Banos. Bill immediately pictured himself a perch one of these power buggies. He took the train for San Francisco. He soon discovered there were only four or five automobiles owned in the city and that there were no agencies where he could buy one. But the Pioneer Automobile Company was taking orders for cars to be shipped out from the East. Bill planked down Seven Hundred Dollars. His order was number Twenty-Two, when the carload came his car would be unloaded for him in Fresno.

Some weeks later Bill was right on hand in Fresno when his car arrived. It was the twenty-second Oldsmobile in California. It was more like a buggy than a modern automobile. Although it had a dashboard it had no windshield, nor was there a steering wheel, instead there was a tiller that lay across the lap of the driver. To get into the drivers seat this iron bar had to be raised. The wheels had wooden spokes and rubber tires. The outside tires were simply canvas, covered over with a little rubber. The inside tubes were rubber. The car had a chain drive. The engine was high up back of the driver's seat. It was one cylinder and was four and a half horsepower. The crankcase was on the right hand side of the car. The gasoline tank held four gallons of gasoline. There was a water tank beside the engine and a couple of coils down under the driver's feet. The water in the tank at the engine would circulate from the engine down through the coils and then back up to the tank. There was no generator or magneto and the car used dry cell batteries. But the car made thirty miles on a gallon of gas.

Because Bill knew how to run a steam engine he had no difficulty in coaxing his new found toy to behave properly the seventy miles from Fresno to Los Banos.

Bill had bought the automobile thinking to use it in hunting ducks. But soon he was running "Firsts" in every direction. He was the first to hunt quail with an automobile. He was the first to reach Mercy Springs in an automobile. He was the first from Los Banos to visit the Pinnacles south of Hollister. Soon Bill became really venturesome, he decided on a trip to Los Angeles!

It took Bill only three or four days to reach Los Angeles. He went by way of Fresno. The first night he stayed at a Mexican ranch down near Bakersfield. The only person in sight when he drove up was a little Spanish boy. He was completely carried away watching this strange buggy. Bill asked him if he thought his folks would let him stay over night. "I dunno." The boy's sole interest was in looking at Bill's automobile. Presently the boy's mother came to the door. "Yes" he could put his buggy in the barn and stay all night. When an older brother returned home after dark nothing would do but the little brother should light the lantern and take his brother out to the barn and show the surprise the little brother had for him, - a buggy with no horse to pull it. The next morning when Bill was ready to leave. "No, Senor. Our home is your home".

From Bakersfield on towards the mountains to the south the road was terrible. Freight wagons had worn ruts so deep that the axles of the wagons in many places dragged on the ground. Bill had to drive for miles astride these ruts. If he had ever gotten his wheels into one of these ditches he would never have been able to get it out alone. He went by way of Gorham Station and then by Elizabeth Lake, continuing on to Newhall Pass.

Bill was coming down a grade and noticed ahead of him a man driving out of a ranch onto the road. Bill supposed of course that the man would stop until he got down the grade. Instead the man kept right on coming. They met on the grade. Bill pulled to one side hoping the man would be able to pass. Instead his horse tried to turn around in the shafts and refused to come anywhere near Bill's "buggy". The Irishman was furious. He called Bill every name his Irish tongue could muster. Getting out of his buggy he went around back to the boot and took out a long blacksmith's hammer. Bill quickly sensed that the fellow was intending to smash the automobile to pieces. Like all good market hunters Bill always carried his "gat" where he could hold of it handy. His revolver was lying on the automobile seat right beside him. He picked it up and drew a dead bead on the Irishman's head. "Don't try anything like that!" ordered Bill. The battle was over before it began. Bill edged his automobile around the stranded buggy and coasted along down the grade.

Never in his life did so many people in so many languages curse Bill as when he plowed boldly down the main street of Los Angeles. Pandemonium had broken loose. The thoroughfare was filled with horses - carriages - dray teams - horse drawn streetcars. Every horse tried to climb a telephone pole. Every driver was hollering "Whoa" and at the same time cursing Bill at the top of their voice. "Get that contraption out of town!"

Bill was afraid to stop. He kept right on going, he arrived at the other side of Los Angeles. He saw a livery barn, driving up he asked the proprietor if he could park his automobile for a few days in his livery barn. The astonished man, seeing the determined look on Bill's face, meekly answered, "Yes."

A few days later when Bill was ready to start back to Los Banos he knew enough to come around the side of Los Angeles. He got up early in the morning to miss as many horses as possible. He came by way of what is now Hollywood. There was no Hollywood there then. A Soldiers Home stood on a high bluff. Bill wanted to come home by way of the coast. He overtook a Mexican traveling on foot. Bill savvied better than to ask him how to get to San Francisco. That would be much to ask of a man traveling on foot. He asked the man how to get to Santa Barbara. "You follow this road until you come to Pico's Ranch. Then you ask them the road to Castro's hacienda. Then you go on for quite a bit until you come to the Calabazas Ranch. From there keep asking until you come to Santa Barbara."

In going down a grade on the Canejo Pass on his way to Santa Barbara the car got to running faster and faster. The ocean was on Bill's left about fifty feet down. At a turn in the road a short distance ahead he could see that he was going to go over the cliff. There was a big, tall tree on his right. He headed the car right up the trunk. Bill landed on his feet. In taking stock Bill found that the radiator leaked a little, the front axle was bent a trifle. But his leather brakes were worn nearly to ribbons.

In Santa Barbara a garage was unheard of and machine shops were non-existent. Inquiring around Bill found that an old man was fitting up his boy with a future repair shop. The father evidently could foresee that automobiles were going to be the coming thing and sensed that machine shops would be needed to keep them running.

Bill located the young man's shop. Evidently some machine company had rigged up the place for the boy. All the machines, lathes and welding tools were new and first class. The young man told Bill that he didn't know yet how to run the machinery. Bill explained that would make no difference, that he could make the repairs of on the car if he could use the machinery. Bill stayed two or three days turning out brake drums and new brakes for his car. The boy was so delighted with what Bill taught him about machinery that he would take nothing for the use of his shop.

Bill was almost home; he was within five mile of San Jaun Batista. There was a little bridge over an inviting stream. Bill decided to get some water for his leaking radiator. When Bill cranked up the engine again and climbed back in the seat the car stood stock-still. Bill realized that his journey was ended. He knew that the crankshaft was broken.

Bill walked to San Juan Bautista where he hired a drayman to come with a couple of planks and haul the automobile into town. Together they ran the helpless machine up on the planks onto the back end of the dray and hauled it to a blacksmith's shop in San Juan. An old French locksmith had running the shop for years. The Frenchman was flabbergasted, to think that he was qualified to work on an automobile! For him to repair such complicated machinery. "Impossible!"

Bill assured the old man that if he would let him have the use of his "fire" and some of his tools he believed that he could fix the crankshaft himself. The old man looked on in amazement as Bill worked. Bill drilled three holes through the broken crankshaft. Then he looked around the shop for some steel teeth from and old hay rake. He cut off three pieces of about four inches, straightened them and filed them to fit the holes he had bored. The chalked the broken shaft and lined up the two parts as true as he possibly could. He drilled three holes in the broken part. With a sledgehammer he pounded the two parts together. "Well, I take my hat off to you," declared the old blacksmith.

Bill was three weeks on his trip to Los Angeles. In all that time he saw nary an automobile on the road. Whenever Bill would stop in a town even just to get a drink of water, the crowd that would gather would be so dense that he could hardly get back to his machine.

Bill came home by way of Pacheco Pass. It was then but a wagon road. When he got to Los Banos his car was running better than ever. He had already ordered new parts in San Francisco. They arrived from the east weeks later. "Do you know," chuckled Bill Gleefully "I never did put in those new parts!"?

Anybody could fix one... People got up their courage and soon everybody was riding in Automobiles."

Source: ENTERPRISE, Los Banos, Cal., Thursday, October 1, 1970, Section A-7