My grandfather's grave is in the Westville Cemetery but there is no headstone and I do not know where his grave is located. I would like to have a headstone set for him and would appreciate being notified by someone who could specify where his grave is in the Westville Cemetery.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

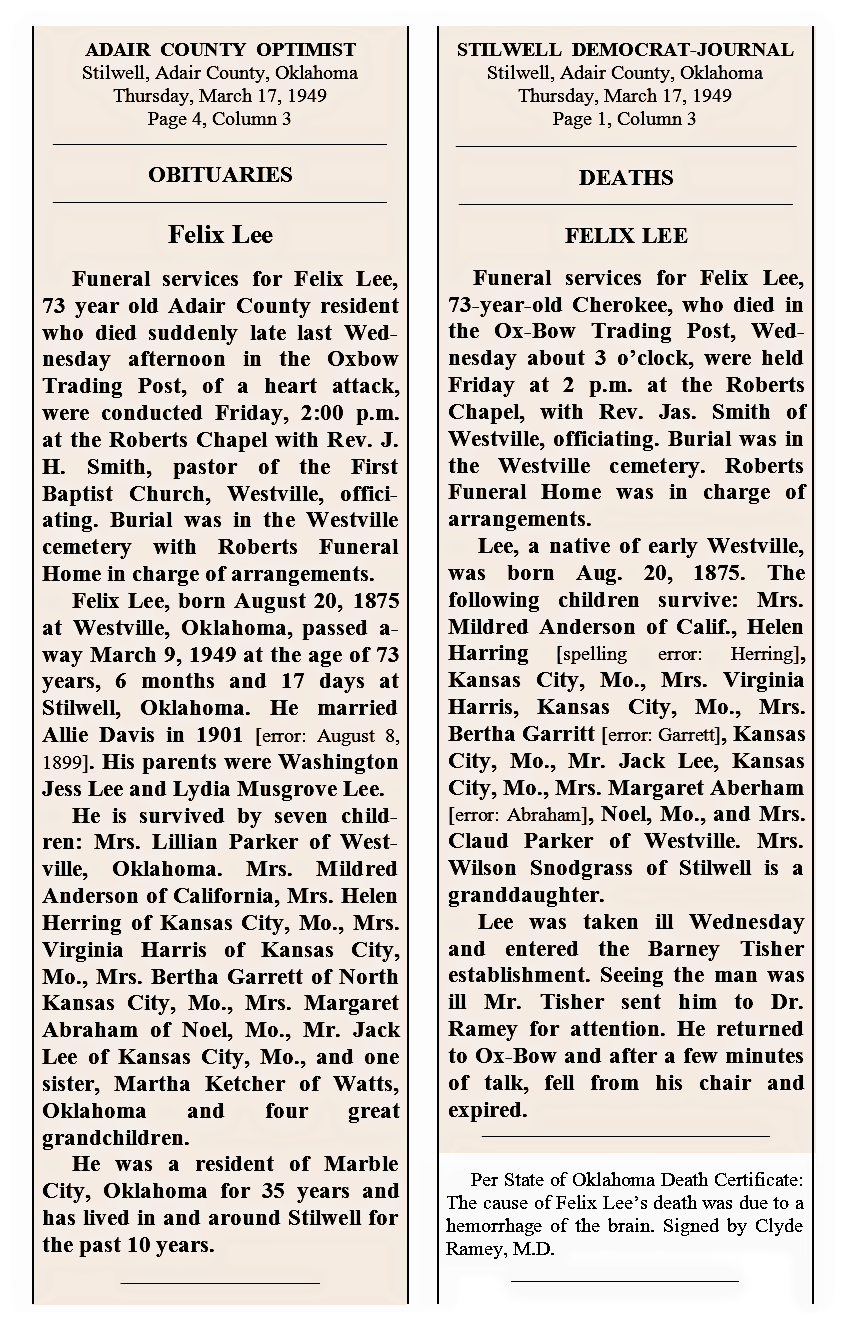

Felix LEE was born in the Going Snake District, Cherokee Nation West, Indian Territory on August 20, 1875 to Washington Jess and Lydia Ann (née MUSGROVE a.k.a. TUCKER) LEE. He was the first son and third child of seven children born to "Wash" and "Liddie" LEE. Felix was born at home northwest of present-day Westville, Adair County, Oklahoma and southwest of the intersection of Highway 59 and Chewey Drive. On Google maps the site is designated as Lydia Lee Springs, Oklahoma (Ghost Town); it was named for Wash's wife, Lydia LEE, and the spring which originated on their property and was used by the community for a source of fresh cool water.

The LEE Family were Native Americans and Cherokee-by-blood citizens of the Cherokee Nation. Felix's father, Wash LEE, was born east of the Mississippi River in northwestern Georgia, Old Cherokee Nation East and was orphaned on the Trail of Tears during 1838/1839. Felix's mother, Liddie MUSGROVE, was born in the Going Snake District, Cherokee Nation West to William Alexander and Nancy (née TUCKER) MUSGROVE. William was born in Virginia and was of Scotch-Irish descent. Nancy was a Cherokee-by-blood Native American and traveled from the Old Cherokee Nation East to the Cherokee Nation West prior to the Trail of Tears; she was among the Cherokees known as Old Settlers. Wash and Lydia met after the U. S. Civil War, married ca 1869, and made the Going Snake District, Cherokee Nation West their lifelong home.

The LEEs were a prominent family in the area. Wash served as a Union soldier during the Civil War, and after the war he was a member of the mounted Indian police force known as the National Light-Horse Company. In 1881, he was elected Sheriff of the Going Snake District and served a two year term. The LEE Family was very active in their community and the Cherokee tribe.

On September 27, 1890, Wash was shot five times during an ambush on his property by two men. Neighbors carried him to his home and a doctor was summoned, but his wounds were too severe. He died at home, surrounded by family and friends, three days after the unwarranted attack.

At the time of Wash LEE's death, his wife Lydia was 49 and their seven children were: daughter Martha, 20 (wife of George KETCHER, 29, and a mother of two sons: Lee, 3 and Henry, 2); daughter Nannie, 18; son Felix, 15; daughter Carrie, 13; daughter Sallie, 11; daughter Katie, 9; and son Levi, 6. Wash's family suffered the loss of a loving, nurturing husband, father, and grandfather. His murder took a good man from his family and from their community; Lydia never remarried.

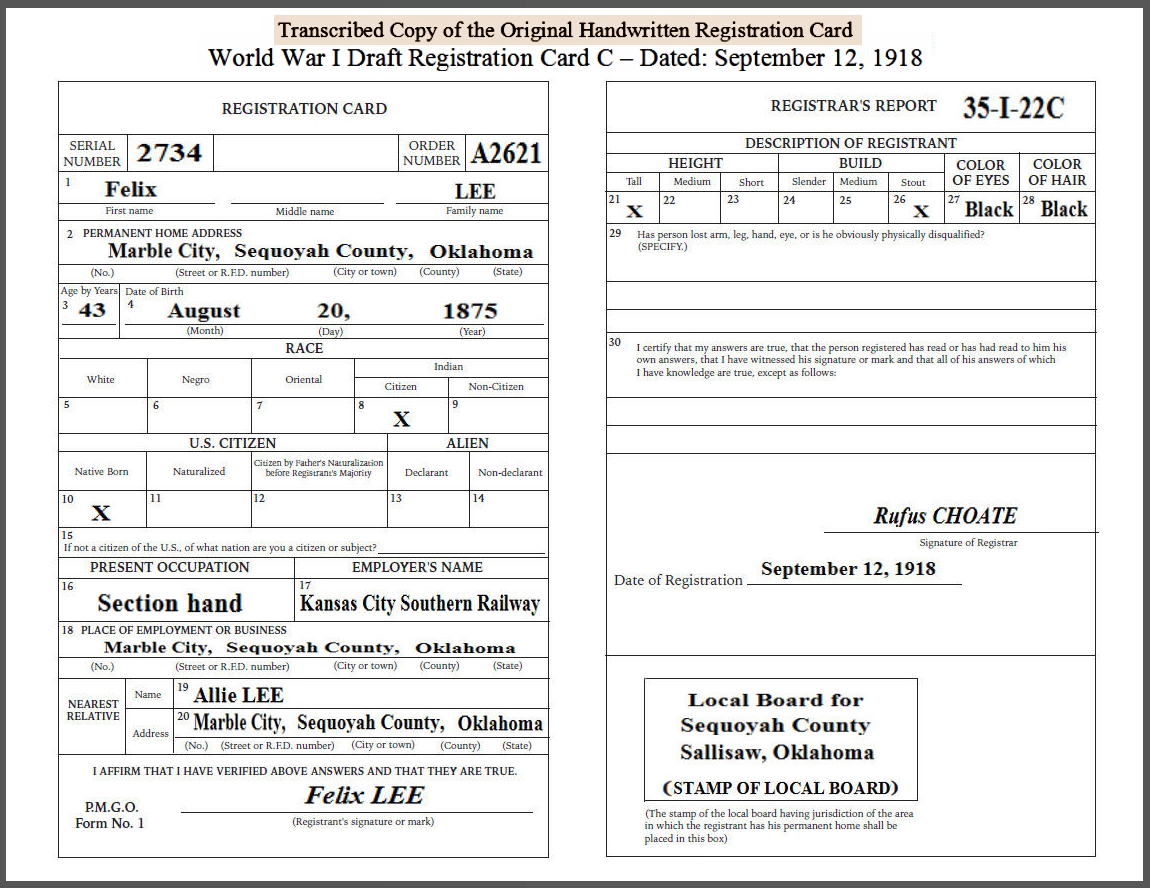

On August 8, 1899, Felix LEE, 23, and Allie DAVIS, 24, both of Baptist, Going Snake District were married in the Northern District (a United States Federal Courts Recording District in Indian Territory with Court Seats in Vinita, Miami, Tahlequah and Muskogee; their marriage is recorded in Book I, page 110, at the court in present-day Muskogee, Muskogee County, Oklahoma). They made their home in the Going Snake District until about 1902 when they moved near Marble in the Sequoyah District, Cherokee Nation West (present-day Marble City, Sequoyah County, Oklahoma). There they raised six daughters and one son: Lucilla Lillian; Myrtle Mildred, Felix Helen a.k.a. Helen Marie; Kate Clifton a.k.a. Virginia/"Cliff"; Bertha Alice a.k.a. Barbara/"Bertin"; Cornelius a.k.a. Jack Leroy/"Bud"; and Margaret Karoline a.k.a. "Maggie".

On Saturday afternoon, September 30, 1911, at approximately 12 p.m., Felix LEE, Wolf PORTER, Ed SANDERS, Barney TISHER, Ernest WILLIAMS, and Clifford WOODWARD were fighting in an alley behind the Marble City hotel when Marshall John T. KIRK attempted to disperse the brawl. After Marshal KIRK stepped in to halt the conflict between the six men, he was struck "over the head with some blunt instrument" and died two days later from the blow.

The six men were arrested that same day and held in jail at Sallisaw, Oklahoma to await a preliminary hearing for the assault upon Marshall KIRK. At the hearing on October 16th, all six were charged with the killing of J. T. KIRK, town Marshall of Marble City, and bound over without bail to await trial during the January 1912 term of the District Court. The case against Ed SANDERS was the first trial held regarding the accused; it began January 19th and concluded the following day on the 20th. After 40 minutes of deliberation, the jury found Ed SANDERS not guilty.

The second trial concerned the case against Barney TISHER; it began on Monday morning, January 22nd and was given to the jury on Thursday, January 25th, at 11:00 a.m. The jury of twelve men was unable to reach a verdict. They deadlocked at nine for acquittal and three for conviction; a mistrial was declared.

Testimony given by witnesses during the SANDERS and TISHER trials supported that Barney TISHER acted alone in delivering the blow upon Marshall KIRK; as a result, all charges were dismissed against the four remaining defendants awaiting trial and they were released from custody. The court ruled that Barney TISHER would remain as the only defendant charged with the crime of manslaughter and his second trial would be held at the next District Court term; while awaiting that trial, he was released at liberty on a $10,000 bond.

On March 19, 1912, Barney TISHER was shot at 8 p.m. on the steps of the Marble City Post Office. He received three shots to his legs; one was a glancing shot, another lodged in the left leg below the knee, and the third broke the thigh bone in the right leg. He was taken to the hospital in Fort Smith, Arkansas to recover. TISHER accused John Esta KIRK, the 27-year-old son of Marshal John T. KIRK, of the shooting and made formal charges against him. KIRK was placed under arrest about 10 p.m. the evening of the shooting and taken to Sallisaw. Due to there being only circumstantial evidence against him, he was later released on a low bond of $500. At his examining trial on May 2, 1912, he was not charged for the TISHER shooting due to lack of evidence and witnesses to testify against him.

On May 5, 1913, the case of the State vs. Barney TISHER charged with the murder of Marshall KIRK was stricken from the docket due to the county attorney deciding it would be useless to further prosecute the case.

Newspapers of the day often sensationalized the first reports of local news events. Anyone doing historical research should keep in mind that they may not have found a factual account of an event being reported by a newspaper, but possibly a tabloid journalism piece written to temporarily boost sales. One of the early articles regarding Marshall John KIRK's murder indicated he "attempted to make the human fiends come within the bounds of the law when he was pounced upon by the ... troubadours of vice and crime, who with the use of clubs, beat the dutiful marshal into insensibility, in which he remained until his death. ... The names of the hydra-headed human hyenas are as follows, the first three being Cherokees, Ed SANDERS, Wolf PORTER, Felix LEE, Barney TISHER, Earnest WILLIAMS, Clifford WOODWARD."

The 1911 tabloid article reference above unfortunately went to press in a multi-volume historical account of Marble City (published circa 2007) without the article's contents being researched to verify it for accuracy and without any other information being provided regarding the death of the sheriff or the innocent men accused.

In 1911, Marble City was a town of about 340 to 350 people. Marshall KIRK had been a member of the community, was known by most, and was a friend and neighbor to several. He may have walked confidently into the fight because he knew most if not all of the men involved and believed they would disperse once he quieted the situation. Most of the men were so involved in their one-on-one combat (reportedly three Caucasian men fighting the three Native American men) that the majority of the combatants and witnesses to the fight didn't realize the Marshall was endangered until it was too late.

Felix LEE never envisioned a fist fight would lead to the death of a friend and neighbor. His father, former Sheriff Wash LEE, had been murdered, and Felix never thought he would ever be involved in a similar event that would inflict such horrible pain and sorrow on another person's spouse, children, and grandchildren. Marshall KIRK's death and the KIRK family's pain of their loss hit Felix hard and he swore to never take part in another fight.

Maggie, Felix's youngest child, grew up knowing of her father's resolve to not be drawn into fights, and she was aware of only one time, as she was growing up, when he came close to hitting a man. She recalled that incident as follows: The construction of the railroad through Oklahoma bought on the need for railroad ties to be delivered out to where new train tracks were being laid. Times were rough and several families needed money so some of the men in the area decided to start cutting railroad ties to sell to the railroad. These men made arrangements with Felix LEE for him to use his team and wagon to haul the ties to Marble City for sale to the railroad. Business was so good, that he hired a white man, Homer HORNET, to help him. His terms to the man when he agreed to hire him were: the horses were never to be whipped or mistreated, the wagon was not to be overloaded, the horses were always to have adequate food and water, etc.

Homer's job was to take the wagon over to where the railroad ties were made, wait while the men loaded the ties onto the wagon, then deliver the ties to Marble City and wait until the men who bought the ties unloaded the wagon; he was to make two trips per day. Felix paid Homer for each day he hauled ties and also allowed him to stay with the Lee family at their home. Unfortunately, it wasn't long before word came back to Felix that men had seen Homer on the Marble City Main Street with an overloaded wagon beating the horses in an attempt to force them to pull the heavy load.

Maggie had never seen her father mad before, but upon the news of the mistreatment of the horses, she saw the anger instantly well up in him as he turned to her to tell her to stay at the house with her mother. As she described it, "He was so angry over what he had been told that blood came into the whites of his eyes" (meaning the blood vessels of the eyes became swollen giving the appearance of the white of the eye becoming red possibly due to a rise in blood pressure). As she stood stunned before him, he abruptly turned around and left with the men who had delivered the news. As Felix arrived at the scene, the hired man was still in the process of whipping the team and Felix confronted him about the brutal treatment of the horses.

Homer argued that beating the horses was the only way to get them to do what he wanted and he couldn't understand why Felix believed so strongly that you never treat a team or any animal that way. In frustration and anger, Felix reached up from the side of the wagon to pull the whip out of the man's hands. The hired man tried to maintain his grip on the whip but lost his grip and fell off the side of the wagon to the ground. Felix looked down at the man on the ground and warned, "If you know what's good for you, don't even think of getting up looking for a fight. You're fired! Now, get out of my sight!" Without a word, the man took off out of town while Felix was helped by some of his neighbors with the battered horses. Rumors in the community later indicated that Homer had left the county never to return.

The Felix and Allie (née DAVIS) LEE family were established members of the Marble City community and well-liked. After moving to Marble City, Felix spent a number of years working at the quarry near the city before becoming self-employed with the hauling of railroad ties and the hunting of skunks, possums, raccoons, and an occasional red fox for their pelts to sell. A red fox pelt was the most valuable followed by the raccoon pelt. Felix was an excellent shot and never had a problem bringing down what his hunting dogs treed. He would skin the game and cure their hides on boards placed at the north side of the house. The carcasses of the animals were cooked outdoors in a large black kettle for his dogs to eat. When enough pelts had been cured for a wagon load, Felix would drive the wagon load to a nearby trading post to sell the pelts. Between the railroad ties and pelts, he managed a good income for his family. Eventually, he was employed by the railroad on jobs which often required him to be away from his family for periods of time. Those jobs included work as a section hand and as a lookout along a particular hillside known for mud and rock slides. As a lookout, his job was to stop trains before they were derailed from encountering the slide on the rails; during his service as a lookout all derailment of trains due to mud and rock slides ceased on his watch.

His wife, Allie, after being admitted in and out of hospitals for a period covering about ten years, preceded him in death by six years due to cancer of the liver. When one of their older daughters and her family were staying with Felix, his log cabin burned. His daughter had placed an oversized log in a cast iron wood burning stove with part of the log protruding out of the stove thus preventing its door from being closed. As the stick of firewood burned in the stove, the overhanging part of the log dropped to the wood floor of the kitchen and caught the house on fire. Everyone got out safely, but there wasn't enough time to save any belongings. The items they hated losing the most were the family photographs, especially the framed picture of Allie with her sisters which had hung on the wall near the front door.

Following the house fire, Felix began traveling during his late fifties through his early seventies to stay for periods of time at the homes of his children and grandchildren. In December 1939, he traveled to Kansas City, Missouri to spend time with his youngest child, Maggie, her husband Jim ABRAHAM, and their daughter, Barbara. He arrived with an early Christmas present for Maggie and her family -- a box of electric, multicolored, Christmas tree lights! They had never had electric lights for their Christmas tree before; it was a very special and beautiful gift that they enjoyed throughout the holidays!!

Barbara was in kindergarten and she remembers Grandpa Felix as a quiet, gentle man, well-groomed with some gray interspersed in his dark hair and mustache. He had his hair cut in the style of the day, but unlike some men, he didn't use hair crème for styling; his hair was short, natural, and soft. His mustache was full, neatly trimmed, with the ends tapering to just a slightly longer length. He appeared to be tanned but being part Native American that was his natural skin color. His face was smooth with only a few moderate lines on his forehead and at the outer corners of his dark brown eyes when he smiled or laughed. Each morning of his stay, he enjoyed sitting at the breakfast table with a cup of coffee while browsing through the newspaper.

Grandpa Felix was a good observer and listener; he sensed that Barbara was bothered by something, but she hadn't chosen to speak about whatever it was. He asked her if he could walk her to school in the mornings and then come to walk her home when school let out in the afternoon; she happily said, "Yes!" During their walk to school, Barbara opened up and told him there were some older kids that bullied her every morning on her way to school and she was afraid of them. She never encountered the "mean" kids on her way home from school because they attended a full day of school while Barbara, as a kindergartner, went only a half day until noon. He asked if she always took the same path to school, and she said, "Yes." Felix responded, "It might help if we worked together at finding you different paths to take to school instead of just your one path. By having a variety of paths to choose from, you could avoid the bullies waiting on the path they expect you to take by choosing one of your other paths."

Barbara enjoyed the adventure of discovering multiple paths with her grandfather during the days that followed. After they worked out the paths, Grandpa Felix began walking with her part way in the mornings then would wait while she continued on by herself. She watched for the bullies then would choose a path where they couldn't see her so she could avoid them; Grandpa observed the school from a distance to ensure that the bullies didn't notice Barbara while she went into the school. When Grandpa Felix's visit ended, Barbara missed him and their time together, but following the advice of her Grandpa, she never again had trouble with bullies at school. Grandpa Felix passed away before I was born, but the sage advice he gave my sister, Barbara, helped me years later when I was targeted by bullies.

Felix LEE was a man who loved family, friends, and the outdoors. He taught his children to respect people, nature, and animals. As a Cherokee, he mourned the loss as the Native American tribes and their way of life diminished due to tribal communal lands being progressively seized from the Indian nations by the United States Government.

In 1817, President James Monroe had promised a delegation from the Western Cherokee in Arkansas:

"As long as water flows, or grass grows upon the earth, or the sun rises to show your pathway, or you kindle your camp fires, so long shall you be protected by this Government, and never again removed from your present habitations."

Promises to the tribes, such as President Monroe's, failed to be kept; to date the more than five hundred treaties with the Native American tribes have all been broken, nullified or amended by the U. S. Government. The generations of his father and Felix's experienced the diminishing presence of indigenous Native American cultures at an unprecedented rate through the aggressive displacement by the Western culture's Indian removal policies. Felix's father, Wash, had been among the many Native Americans during the 1830s removed by force of arms from their ancestral homelands east of the Mississippi River to territory west of the river. This western land had been designated by the U. S. Government for several tribal nations driven from the East (i.e., the Five Civilized Tribes: Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee a.k.a. Creek, and Seminole; as well as several other tribes: the Wyandot, Kickapoo, Potawatomi, Shawnee, Lenape, etc.).

On March 23, 1829, prior to the aggressive removal of the many tribes from east of the Mississippi River, President Andrew JACKSON sent a letter to the Creek Nation, it stated:

"Friends & Brothers, By permission of the Great Spirit above, and the voice of the people, I have been made a President of the United States, and now speak to you as your Father and friend, and request you to listen. Your warriors have known me long. You know I love my white and red children, and always speak straight, and not with a forked tongue; that I have always told you the truth. I now speak to you, as to my children, in the language of truth -- listen.

... Where you now are, you and my white children are too near to each other to live in harmony and peace. ... Beyond the great river Mississippi, where a part of your nation has gone, your Father has provided a country large enough for all of you, and he advises you to remove to it. There your white brothers will not trouble you; they will have no claim to the land, and you can live upon it, you and all your children, as long as the grass grows or the water runs, in peace and plenty. It will be yours forever."

By 1836, most Creeks had reluctantly relocated voluntarily or been forced from the East to land allotted west of the Mississippi River by the U. S. Government.

During JACKSON's administration, at a meeting held during September 1830, U. S. Representatives threatened the Choctaw people with destruction if their tribal representatives did not sign a final treaty ceding their land in the East. In 1831 near Memphis, Tennessee, Alexis de TOCQUEVILLE, the French historian and political theorist, was witness to a small segment of the forced removal of the Choctaw Nation on foot from their homeland during an exceptionally harsh winter without adequate government provisions. Later he wrote the following about what he had witnessed as the Choctaw people emerged from the forest with many more miles yet to endure:

"In the whole scene there was an air of ruin and destruction, something which betrayed a final and irrevocable adieu; one couldn't watch without feeling one's heart wrung. The Indian were tranquil, but sombre [French word meaning dark, somber, gloomy] and taciturn. There was one who could speak English and of whom I asked why the Chactas [sic] were leaving their country. "To be free," he answered, could never get any other reason out of him. We ... watch the expulsion ... of one of the most celebrated and ancient American peoples."

Upon reaching the land allotted by the government in Indian Territory to the tribe, a Choctaw chief described their removal as a "trail of tears and death".

During 1875, Felix was born in the Cherokee tribal lands relocated within the designated Indian Territory. The promise to Native Americans that Indian Territory "will be yours forever" was short-lived. Within the time frame of less than half of Felix's lifetime, Native Americans experienced the demise of the these western tribal lands as they were reassigned by the U. S. Government from the tribal nations into plots of land for ownership by individuals and companies. This division of tribal lands into tracts or parcels was a precursor to white settlement and the establishment of new states created from Indian Territory. The Cherokee Nation land where Felix had been born plus the land of other tribes relocated from the East to Indian Territory were combined with Oklahoma Territory to form, on November 16, 1907, the 46th state of the United States of America, Oklahoma.

The advancement of the white settlements and the rapid pace of the Second Industrial Revolution proceeded with little conservation of the Earth's ecosystems. Felix observed with great sorrow the relentless destruction of the wild fauna and flora, species becoming extinct due to overhunting and habitat loss, and the unprecedented pollution of air, land, and water. As with most Native Americans, his beliefs were deeply rooted in living in harmony with the Earth and its treasure of life forms to ensure preservation of the quality of life for current and future generations.

In addition to the rapidly diminishing presence of Native American cultures, Felix's life, like so many, encompassed World War I, the 1918-1920 flu pandemic, the Great Depression, and World War II with man's use of a devastating new weapon, atomic bombs. Condensed into a short period of time, his generation, unlike any generation before, faced unbelievable social changes, economic changes, and inventions with not only profound possibilities to improve lives, but also to destroy life. It was a time of difficult challenges and great loss, but also a time of great promise and opportunities.

His generation rose to the best of their ability to meet their challenges. In the process, imperative examples were set for future generations to take note of and be guided by in building understandings between different peoples -- it was a generation that discovered how the United States of America had an unsurpassable strength when its citizens and immigrants of different ethnicities worked together toward common goals for the good of the whole. The needed intellect and skills for the success of the United States during this era were contributed by people from every walk of life and race; countless learned firsthand of the value in one another, including merits of Native Americans.

During World War II, when the total Native American population was less than 350,000, it is estimated that more than 44,000 Native American men and women served in the United States armed forces (including Felix LEE's only son, Jack). They served on all fronts during the war.

Among the Native Americans who served during WWII, several hundred from at least thirty-three tribes served as Code Talkers in the European, Mediterranean, and Pacific theatres (i.e., Apache, Assiniboine (Nakota), Cherokee, Chippewa, Choctaw, Comanche, Creek, Crow, Hopi, Kiowa, Lakota, Menominee, Meskwaki (Fox), Mohawk, Navajo, Oneida, Osage, Pawnee, Ponca, Pueblo, Sauk (Sac), Seminole, Sioux, Tlingit, etc.).

Code Talkers were fluent in both their traditional tribal language and in English. Their crucial duties involved utilizing their native languages as formal and informally developed codes to transmit coded messages to prevent the enemy from interpreting Allied communications regarding tactical operations. Their invaluable service greatly improved the security and the speed of encryption and decryption of military communications. Code Talkers were utilized extensively in battle and were essential to Allied victory (e.g., 5th Marine Division signal officer Major Howard Connor stated, "Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima."). The timely speed with which a code talker could code and send a message as well as receive and decode one was crucial for allied troops requesting or directing artillery, summoning assistance by tanks, or calling in air strikes.

Code Talkers had first served during World War I at a time when several Native Americans had not been accorded the status of United States citizenship (most were not recognized legally as U. S. citizens until 1924 and some states refused to let Native Americans vote until the 1950s). Regardless, an estimated twenty-five percent of the male Native American population enlisted and fought on behalf of the USA. The use of Native Americans for cryptography of tactical messages was pioneered by Cherokee troops in the 30th Infantry Division serving in the Second Battle of the Somme.

The need for Native Americans to use their tribal languages to provide an unbreakable code for the Allies was ironic; beginning in the late 1800s, the U. S. Government pursued attempts to eliminate Native American cultures by forcing Indian children to attend government or religious-run boarding schools where they were punished if they tried to use their native languages and traditions. Speaking at a ceremony in 2013 to honor the service of Code Talkers, Senate Majority Leader Harry REID (Democrat-Nevada) stated:

"In this Nation's hour of greatest need, Native American languages proved to have great value indeed. The United States government turned to a people and a language they had tried to eradicate."

Code Talkers are but one example of how Native American cultures proved to have invaluable worth to the Western culture that nearly eradicated them. In the Western culture's pursuit to take land and resources from the Native Americans, they failed to consider the value of the indigenous people. Their failure to consider the worth of the Native American cultures could have resulted in the fall of the United States of America and its Allies during World War II had they not been able to devise unbreakable communication codes as effective and efficient as the Code Talkers'.

The Native American cultures are among the many cultures on our Earth with inherently good qualities and values that should not be extinguished. To do so would deprive our diverse humanity of each culture's knowledge, strengths, skills, intellect, creativity, and insights; the loss of human potential as well as the prospects of the various cultures' vital contributions would be immeasurable.

-------------------------------------------------------

Biography contributed to Find A Grave by L. ABRAHAM, grandchild of Felix and Allie (DAVIS) LEE.

My grandfather's grave is in the Westville Cemetery but there is no headstone and I do not know where his grave is located. I would like to have a headstone set for him and would appreciate being notified by someone who could specify where his grave is in the Westville Cemetery.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Felix LEE was born in the Going Snake District, Cherokee Nation West, Indian Territory on August 20, 1875 to Washington Jess and Lydia Ann (née MUSGROVE a.k.a. TUCKER) LEE. He was the first son and third child of seven children born to "Wash" and "Liddie" LEE. Felix was born at home northwest of present-day Westville, Adair County, Oklahoma and southwest of the intersection of Highway 59 and Chewey Drive. On Google maps the site is designated as Lydia Lee Springs, Oklahoma (Ghost Town); it was named for Wash's wife, Lydia LEE, and the spring which originated on their property and was used by the community for a source of fresh cool water.

The LEE Family were Native Americans and Cherokee-by-blood citizens of the Cherokee Nation. Felix's father, Wash LEE, was born east of the Mississippi River in northwestern Georgia, Old Cherokee Nation East and was orphaned on the Trail of Tears during 1838/1839. Felix's mother, Liddie MUSGROVE, was born in the Going Snake District, Cherokee Nation West to William Alexander and Nancy (née TUCKER) MUSGROVE. William was born in Virginia and was of Scotch-Irish descent. Nancy was a Cherokee-by-blood Native American and traveled from the Old Cherokee Nation East to the Cherokee Nation West prior to the Trail of Tears; she was among the Cherokees known as Old Settlers. Wash and Lydia met after the U. S. Civil War, married ca 1869, and made the Going Snake District, Cherokee Nation West their lifelong home.

The LEEs were a prominent family in the area. Wash served as a Union soldier during the Civil War, and after the war he was a member of the mounted Indian police force known as the National Light-Horse Company. In 1881, he was elected Sheriff of the Going Snake District and served a two year term. The LEE Family was very active in their community and the Cherokee tribe.

On September 27, 1890, Wash was shot five times during an ambush on his property by two men. Neighbors carried him to his home and a doctor was summoned, but his wounds were too severe. He died at home, surrounded by family and friends, three days after the unwarranted attack.

At the time of Wash LEE's death, his wife Lydia was 49 and their seven children were: daughter Martha, 20 (wife of George KETCHER, 29, and a mother of two sons: Lee, 3 and Henry, 2); daughter Nannie, 18; son Felix, 15; daughter Carrie, 13; daughter Sallie, 11; daughter Katie, 9; and son Levi, 6. Wash's family suffered the loss of a loving, nurturing husband, father, and grandfather. His murder took a good man from his family and from their community; Lydia never remarried.

On August 8, 1899, Felix LEE, 23, and Allie DAVIS, 24, both of Baptist, Going Snake District were married in the Northern District (a United States Federal Courts Recording District in Indian Territory with Court Seats in Vinita, Miami, Tahlequah and Muskogee; their marriage is recorded in Book I, page 110, at the court in present-day Muskogee, Muskogee County, Oklahoma). They made their home in the Going Snake District until about 1902 when they moved near Marble in the Sequoyah District, Cherokee Nation West (present-day Marble City, Sequoyah County, Oklahoma). There they raised six daughters and one son: Lucilla Lillian; Myrtle Mildred, Felix Helen a.k.a. Helen Marie; Kate Clifton a.k.a. Virginia/"Cliff"; Bertha Alice a.k.a. Barbara/"Bertin"; Cornelius a.k.a. Jack Leroy/"Bud"; and Margaret Karoline a.k.a. "Maggie".

On Saturday afternoon, September 30, 1911, at approximately 12 p.m., Felix LEE, Wolf PORTER, Ed SANDERS, Barney TISHER, Ernest WILLIAMS, and Clifford WOODWARD were fighting in an alley behind the Marble City hotel when Marshall John T. KIRK attempted to disperse the brawl. After Marshal KIRK stepped in to halt the conflict between the six men, he was struck "over the head with some blunt instrument" and died two days later from the blow.

The six men were arrested that same day and held in jail at Sallisaw, Oklahoma to await a preliminary hearing for the assault upon Marshall KIRK. At the hearing on October 16th, all six were charged with the killing of J. T. KIRK, town Marshall of Marble City, and bound over without bail to await trial during the January 1912 term of the District Court. The case against Ed SANDERS was the first trial held regarding the accused; it began January 19th and concluded the following day on the 20th. After 40 minutes of deliberation, the jury found Ed SANDERS not guilty.

The second trial concerned the case against Barney TISHER; it began on Monday morning, January 22nd and was given to the jury on Thursday, January 25th, at 11:00 a.m. The jury of twelve men was unable to reach a verdict. They deadlocked at nine for acquittal and three for conviction; a mistrial was declared.

Testimony given by witnesses during the SANDERS and TISHER trials supported that Barney TISHER acted alone in delivering the blow upon Marshall KIRK; as a result, all charges were dismissed against the four remaining defendants awaiting trial and they were released from custody. The court ruled that Barney TISHER would remain as the only defendant charged with the crime of manslaughter and his second trial would be held at the next District Court term; while awaiting that trial, he was released at liberty on a $10,000 bond.

On March 19, 1912, Barney TISHER was shot at 8 p.m. on the steps of the Marble City Post Office. He received three shots to his legs; one was a glancing shot, another lodged in the left leg below the knee, and the third broke the thigh bone in the right leg. He was taken to the hospital in Fort Smith, Arkansas to recover. TISHER accused John Esta KIRK, the 27-year-old son of Marshal John T. KIRK, of the shooting and made formal charges against him. KIRK was placed under arrest about 10 p.m. the evening of the shooting and taken to Sallisaw. Due to there being only circumstantial evidence against him, he was later released on a low bond of $500. At his examining trial on May 2, 1912, he was not charged for the TISHER shooting due to lack of evidence and witnesses to testify against him.

On May 5, 1913, the case of the State vs. Barney TISHER charged with the murder of Marshall KIRK was stricken from the docket due to the county attorney deciding it would be useless to further prosecute the case.

Newspapers of the day often sensationalized the first reports of local news events. Anyone doing historical research should keep in mind that they may not have found a factual account of an event being reported by a newspaper, but possibly a tabloid journalism piece written to temporarily boost sales. One of the early articles regarding Marshall John KIRK's murder indicated he "attempted to make the human fiends come within the bounds of the law when he was pounced upon by the ... troubadours of vice and crime, who with the use of clubs, beat the dutiful marshal into insensibility, in which he remained until his death. ... The names of the hydra-headed human hyenas are as follows, the first three being Cherokees, Ed SANDERS, Wolf PORTER, Felix LEE, Barney TISHER, Earnest WILLIAMS, Clifford WOODWARD."

The 1911 tabloid article reference above unfortunately went to press in a multi-volume historical account of Marble City (published circa 2007) without the article's contents being researched to verify it for accuracy and without any other information being provided regarding the death of the sheriff or the innocent men accused.

In 1911, Marble City was a town of about 340 to 350 people. Marshall KIRK had been a member of the community, was known by most, and was a friend and neighbor to several. He may have walked confidently into the fight because he knew most if not all of the men involved and believed they would disperse once he quieted the situation. Most of the men were so involved in their one-on-one combat (reportedly three Caucasian men fighting the three Native American men) that the majority of the combatants and witnesses to the fight didn't realize the Marshall was endangered until it was too late.

Felix LEE never envisioned a fist fight would lead to the death of a friend and neighbor. His father, former Sheriff Wash LEE, had been murdered, and Felix never thought he would ever be involved in a similar event that would inflict such horrible pain and sorrow on another person's spouse, children, and grandchildren. Marshall KIRK's death and the KIRK family's pain of their loss hit Felix hard and he swore to never take part in another fight.

Maggie, Felix's youngest child, grew up knowing of her father's resolve to not be drawn into fights, and she was aware of only one time, as she was growing up, when he came close to hitting a man. She recalled that incident as follows: The construction of the railroad through Oklahoma bought on the need for railroad ties to be delivered out to where new train tracks were being laid. Times were rough and several families needed money so some of the men in the area decided to start cutting railroad ties to sell to the railroad. These men made arrangements with Felix LEE for him to use his team and wagon to haul the ties to Marble City for sale to the railroad. Business was so good, that he hired a white man, Homer HORNET, to help him. His terms to the man when he agreed to hire him were: the horses were never to be whipped or mistreated, the wagon was not to be overloaded, the horses were always to have adequate food and water, etc.

Homer's job was to take the wagon over to where the railroad ties were made, wait while the men loaded the ties onto the wagon, then deliver the ties to Marble City and wait until the men who bought the ties unloaded the wagon; he was to make two trips per day. Felix paid Homer for each day he hauled ties and also allowed him to stay with the Lee family at their home. Unfortunately, it wasn't long before word came back to Felix that men had seen Homer on the Marble City Main Street with an overloaded wagon beating the horses in an attempt to force them to pull the heavy load.

Maggie had never seen her father mad before, but upon the news of the mistreatment of the horses, she saw the anger instantly well up in him as he turned to her to tell her to stay at the house with her mother. As she described it, "He was so angry over what he had been told that blood came into the whites of his eyes" (meaning the blood vessels of the eyes became swollen giving the appearance of the white of the eye becoming red possibly due to a rise in blood pressure). As she stood stunned before him, he abruptly turned around and left with the men who had delivered the news. As Felix arrived at the scene, the hired man was still in the process of whipping the team and Felix confronted him about the brutal treatment of the horses.

Homer argued that beating the horses was the only way to get them to do what he wanted and he couldn't understand why Felix believed so strongly that you never treat a team or any animal that way. In frustration and anger, Felix reached up from the side of the wagon to pull the whip out of the man's hands. The hired man tried to maintain his grip on the whip but lost his grip and fell off the side of the wagon to the ground. Felix looked down at the man on the ground and warned, "If you know what's good for you, don't even think of getting up looking for a fight. You're fired! Now, get out of my sight!" Without a word, the man took off out of town while Felix was helped by some of his neighbors with the battered horses. Rumors in the community later indicated that Homer had left the county never to return.

The Felix and Allie (née DAVIS) LEE family were established members of the Marble City community and well-liked. After moving to Marble City, Felix spent a number of years working at the quarry near the city before becoming self-employed with the hauling of railroad ties and the hunting of skunks, possums, raccoons, and an occasional red fox for their pelts to sell. A red fox pelt was the most valuable followed by the raccoon pelt. Felix was an excellent shot and never had a problem bringing down what his hunting dogs treed. He would skin the game and cure their hides on boards placed at the north side of the house. The carcasses of the animals were cooked outdoors in a large black kettle for his dogs to eat. When enough pelts had been cured for a wagon load, Felix would drive the wagon load to a nearby trading post to sell the pelts. Between the railroad ties and pelts, he managed a good income for his family. Eventually, he was employed by the railroad on jobs which often required him to be away from his family for periods of time. Those jobs included work as a section hand and as a lookout along a particular hillside known for mud and rock slides. As a lookout, his job was to stop trains before they were derailed from encountering the slide on the rails; during his service as a lookout all derailment of trains due to mud and rock slides ceased on his watch.

His wife, Allie, after being admitted in and out of hospitals for a period covering about ten years, preceded him in death by six years due to cancer of the liver. When one of their older daughters and her family were staying with Felix, his log cabin burned. His daughter had placed an oversized log in a cast iron wood burning stove with part of the log protruding out of the stove thus preventing its door from being closed. As the stick of firewood burned in the stove, the overhanging part of the log dropped to the wood floor of the kitchen and caught the house on fire. Everyone got out safely, but there wasn't enough time to save any belongings. The items they hated losing the most were the family photographs, especially the framed picture of Allie with her sisters which had hung on the wall near the front door.

Following the house fire, Felix began traveling during his late fifties through his early seventies to stay for periods of time at the homes of his children and grandchildren. In December 1939, he traveled to Kansas City, Missouri to spend time with his youngest child, Maggie, her husband Jim ABRAHAM, and their daughter, Barbara. He arrived with an early Christmas present for Maggie and her family -- a box of electric, multicolored, Christmas tree lights! They had never had electric lights for their Christmas tree before; it was a very special and beautiful gift that they enjoyed throughout the holidays!!

Barbara was in kindergarten and she remembers Grandpa Felix as a quiet, gentle man, well-groomed with some gray interspersed in his dark hair and mustache. He had his hair cut in the style of the day, but unlike some men, he didn't use hair crème for styling; his hair was short, natural, and soft. His mustache was full, neatly trimmed, with the ends tapering to just a slightly longer length. He appeared to be tanned but being part Native American that was his natural skin color. His face was smooth with only a few moderate lines on his forehead and at the outer corners of his dark brown eyes when he smiled or laughed. Each morning of his stay, he enjoyed sitting at the breakfast table with a cup of coffee while browsing through the newspaper.

Grandpa Felix was a good observer and listener; he sensed that Barbara was bothered by something, but she hadn't chosen to speak about whatever it was. He asked her if he could walk her to school in the mornings and then come to walk her home when school let out in the afternoon; she happily said, "Yes!" During their walk to school, Barbara opened up and told him there were some older kids that bullied her every morning on her way to school and she was afraid of them. She never encountered the "mean" kids on her way home from school because they attended a full day of school while Barbara, as a kindergartner, went only a half day until noon. He asked if she always took the same path to school, and she said, "Yes." Felix responded, "It might help if we worked together at finding you different paths to take to school instead of just your one path. By having a variety of paths to choose from, you could avoid the bullies waiting on the path they expect you to take by choosing one of your other paths."

Barbara enjoyed the adventure of discovering multiple paths with her grandfather during the days that followed. After they worked out the paths, Grandpa Felix began walking with her part way in the mornings then would wait while she continued on by herself. She watched for the bullies then would choose a path where they couldn't see her so she could avoid them; Grandpa observed the school from a distance to ensure that the bullies didn't notice Barbara while she went into the school. When Grandpa Felix's visit ended, Barbara missed him and their time together, but following the advice of her Grandpa, she never again had trouble with bullies at school. Grandpa Felix passed away before I was born, but the sage advice he gave my sister, Barbara, helped me years later when I was targeted by bullies.

Felix LEE was a man who loved family, friends, and the outdoors. He taught his children to respect people, nature, and animals. As a Cherokee, he mourned the loss as the Native American tribes and their way of life diminished due to tribal communal lands being progressively seized from the Indian nations by the United States Government.

In 1817, President James Monroe had promised a delegation from the Western Cherokee in Arkansas:

"As long as water flows, or grass grows upon the earth, or the sun rises to show your pathway, or you kindle your camp fires, so long shall you be protected by this Government, and never again removed from your present habitations."

Promises to the tribes, such as President Monroe's, failed to be kept; to date the more than five hundred treaties with the Native American tribes have all been broken, nullified or amended by the U. S. Government. The generations of his father and Felix's experienced the diminishing presence of indigenous Native American cultures at an unprecedented rate through the aggressive displacement by the Western culture's Indian removal policies. Felix's father, Wash, had been among the many Native Americans during the 1830s removed by force of arms from their ancestral homelands east of the Mississippi River to territory west of the river. This western land had been designated by the U. S. Government for several tribal nations driven from the East (i.e., the Five Civilized Tribes: Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee a.k.a. Creek, and Seminole; as well as several other tribes: the Wyandot, Kickapoo, Potawatomi, Shawnee, Lenape, etc.).

On March 23, 1829, prior to the aggressive removal of the many tribes from east of the Mississippi River, President Andrew JACKSON sent a letter to the Creek Nation, it stated:

"Friends & Brothers, By permission of the Great Spirit above, and the voice of the people, I have been made a President of the United States, and now speak to you as your Father and friend, and request you to listen. Your warriors have known me long. You know I love my white and red children, and always speak straight, and not with a forked tongue; that I have always told you the truth. I now speak to you, as to my children, in the language of truth -- listen.

... Where you now are, you and my white children are too near to each other to live in harmony and peace. ... Beyond the great river Mississippi, where a part of your nation has gone, your Father has provided a country large enough for all of you, and he advises you to remove to it. There your white brothers will not trouble you; they will have no claim to the land, and you can live upon it, you and all your children, as long as the grass grows or the water runs, in peace and plenty. It will be yours forever."

By 1836, most Creeks had reluctantly relocated voluntarily or been forced from the East to land allotted west of the Mississippi River by the U. S. Government.

During JACKSON's administration, at a meeting held during September 1830, U. S. Representatives threatened the Choctaw people with destruction if their tribal representatives did not sign a final treaty ceding their land in the East. In 1831 near Memphis, Tennessee, Alexis de TOCQUEVILLE, the French historian and political theorist, was witness to a small segment of the forced removal of the Choctaw Nation on foot from their homeland during an exceptionally harsh winter without adequate government provisions. Later he wrote the following about what he had witnessed as the Choctaw people emerged from the forest with many more miles yet to endure:

"In the whole scene there was an air of ruin and destruction, something which betrayed a final and irrevocable adieu; one couldn't watch without feeling one's heart wrung. The Indian were tranquil, but sombre [French word meaning dark, somber, gloomy] and taciturn. There was one who could speak English and of whom I asked why the Chactas [sic] were leaving their country. "To be free," he answered, could never get any other reason out of him. We ... watch the expulsion ... of one of the most celebrated and ancient American peoples."

Upon reaching the land allotted by the government in Indian Territory to the tribe, a Choctaw chief described their removal as a "trail of tears and death".

During 1875, Felix was born in the Cherokee tribal lands relocated within the designated Indian Territory. The promise to Native Americans that Indian Territory "will be yours forever" was short-lived. Within the time frame of less than half of Felix's lifetime, Native Americans experienced the demise of the these western tribal lands as they were reassigned by the U. S. Government from the tribal nations into plots of land for ownership by individuals and companies. This division of tribal lands into tracts or parcels was a precursor to white settlement and the establishment of new states created from Indian Territory. The Cherokee Nation land where Felix had been born plus the land of other tribes relocated from the East to Indian Territory were combined with Oklahoma Territory to form, on November 16, 1907, the 46th state of the United States of America, Oklahoma.

The advancement of the white settlements and the rapid pace of the Second Industrial Revolution proceeded with little conservation of the Earth's ecosystems. Felix observed with great sorrow the relentless destruction of the wild fauna and flora, species becoming extinct due to overhunting and habitat loss, and the unprecedented pollution of air, land, and water. As with most Native Americans, his beliefs were deeply rooted in living in harmony with the Earth and its treasure of life forms to ensure preservation of the quality of life for current and future generations.

In addition to the rapidly diminishing presence of Native American cultures, Felix's life, like so many, encompassed World War I, the 1918-1920 flu pandemic, the Great Depression, and World War II with man's use of a devastating new weapon, atomic bombs. Condensed into a short period of time, his generation, unlike any generation before, faced unbelievable social changes, economic changes, and inventions with not only profound possibilities to improve lives, but also to destroy life. It was a time of difficult challenges and great loss, but also a time of great promise and opportunities.

His generation rose to the best of their ability to meet their challenges. In the process, imperative examples were set for future generations to take note of and be guided by in building understandings between different peoples -- it was a generation that discovered how the United States of America had an unsurpassable strength when its citizens and immigrants of different ethnicities worked together toward common goals for the good of the whole. The needed intellect and skills for the success of the United States during this era were contributed by people from every walk of life and race; countless learned firsthand of the value in one another, including merits of Native Americans.

During World War II, when the total Native American population was less than 350,000, it is estimated that more than 44,000 Native American men and women served in the United States armed forces (including Felix LEE's only son, Jack). They served on all fronts during the war.

Among the Native Americans who served during WWII, several hundred from at least thirty-three tribes served as Code Talkers in the European, Mediterranean, and Pacific theatres (i.e., Apache, Assiniboine (Nakota), Cherokee, Chippewa, Choctaw, Comanche, Creek, Crow, Hopi, Kiowa, Lakota, Menominee, Meskwaki (Fox), Mohawk, Navajo, Oneida, Osage, Pawnee, Ponca, Pueblo, Sauk (Sac), Seminole, Sioux, Tlingit, etc.).

Code Talkers were fluent in both their traditional tribal language and in English. Their crucial duties involved utilizing their native languages as formal and informally developed codes to transmit coded messages to prevent the enemy from interpreting Allied communications regarding tactical operations. Their invaluable service greatly improved the security and the speed of encryption and decryption of military communications. Code Talkers were utilized extensively in battle and were essential to Allied victory (e.g., 5th Marine Division signal officer Major Howard Connor stated, "Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima."). The timely speed with which a code talker could code and send a message as well as receive and decode one was crucial for allied troops requesting or directing artillery, summoning assistance by tanks, or calling in air strikes.

Code Talkers had first served during World War I at a time when several Native Americans had not been accorded the status of United States citizenship (most were not recognized legally as U. S. citizens until 1924 and some states refused to let Native Americans vote until the 1950s). Regardless, an estimated twenty-five percent of the male Native American population enlisted and fought on behalf of the USA. The use of Native Americans for cryptography of tactical messages was pioneered by Cherokee troops in the 30th Infantry Division serving in the Second Battle of the Somme.

The need for Native Americans to use their tribal languages to provide an unbreakable code for the Allies was ironic; beginning in the late 1800s, the U. S. Government pursued attempts to eliminate Native American cultures by forcing Indian children to attend government or religious-run boarding schools where they were punished if they tried to use their native languages and traditions. Speaking at a ceremony in 2013 to honor the service of Code Talkers, Senate Majority Leader Harry REID (Democrat-Nevada) stated:

"In this Nation's hour of greatest need, Native American languages proved to have great value indeed. The United States government turned to a people and a language they had tried to eradicate."

Code Talkers are but one example of how Native American cultures proved to have invaluable worth to the Western culture that nearly eradicated them. In the Western culture's pursuit to take land and resources from the Native Americans, they failed to consider the value of the indigenous people. Their failure to consider the worth of the Native American cultures could have resulted in the fall of the United States of America and its Allies during World War II had they not been able to devise unbreakable communication codes as effective and efficient as the Code Talkers'.

The Native American cultures are among the many cultures on our Earth with inherently good qualities and values that should not be extinguished. To do so would deprive our diverse humanity of each culture's knowledge, strengths, skills, intellect, creativity, and insights; the loss of human potential as well as the prospects of the various cultures' vital contributions would be immeasurable.

-------------------------------------------------------

Biography contributed to Find A Grave by L. ABRAHAM, grandchild of Felix and Allie (DAVIS) LEE.

Gravesite Details

No headstone, unmarked grave.

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement